In mechanical engineering, the design and modeling of straight bevel gears are crucial for transmitting motion and power between intersecting shafts. As a type of conical gear, the straight bevel gear features teeth that taper from the larger end toward the apex, making its three-dimensional modeling particularly challenging due to varying tooth profiles at different sections. Traditional approaches often approximate the tooth profile using involute curves from the back cone, leading to inaccuracies. In this article, I present a precise method for modeling straight bevel gears based on the principles of tooth surface generation, utilizing SolidWorks’ capabilities. This method, known as the boundary surface technique, ensures high accuracy by deriving spherical involute curves for both the large and small ends of the gear tooth. By integrating mathematical models with practical software steps, I aim to provide a comprehensive guide for engineers and designers working with straight bevel gears.

The foundation of accurately modeling a straight bevel gear lies in understanding its tooth surface formation. Unlike cylindrical gears, the teeth of a straight bevel gear are generated on a spherical surface, requiring a detailed mathematical representation. The tooth surface is formed by the rolling motion of a generating plane on the base cone, resulting in spherical involute curves. These curves define the precise geometry of the gear teeth and are essential for digital modeling. In this section, I derive the parametric equations for the spherical involute curves at both the large and small ends of the straight bevel gear. This involves establishing coordinate systems and applying transformations to capture the gear’s unique geometry.

To begin, consider the fixed coordinate system \( S(x, y, z) \), where the origin \( O \) is at the apex of the base cone. The z-axis aligns with the cone’s axis, pointing from the apex toward the base, while the x-axis coincides with the starting point of the spherical involute on the base circle. The y-axis is determined by the right-hand rule. An auxiliary moving coordinate system \( S_1(x_1, y_1, z_1) \) is introduced, with its z1-axis as the instantaneous rotation axis during the pure rolling of the generating plane. The parametric equations for a point on the spherical involute in \( S_1 \) are given by:

$$ x_1 = R \sin(\psi) $$

$$ y_1 = 0 $$

$$ z_1 = R \cos(\psi) $$

Here, \( R \) is the cone distance, and \( \psi \) is the angle between the generatrix and the instantaneous rotation axis. The relationship between \( \psi \) and the rotation angle \( \phi \) on the base cone is derived from the pure rolling condition, leading to \( \psi = \phi \sin(\delta_b) \), where \( \delta_b \) is the base cone angle. Substituting this into the equations, the coordinates in \( S_1 \) become:

$$ x_1 = R \sin(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) $$

$$ y_1 = 0 $$

$$ z_1 = R \cos(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) $$

Transforming these coordinates to the fixed system \( S \) using rotation matrices yields the parametric equations for the large-end spherical involute. The transformation involves matrices \( M_1 \) and \( M_2 \), which account for the rotation about the z-axis and the base cone angle, respectively. The resulting equations for the large-end spherical involute are:

$$ Q_x(\phi) = R \left[ \cos(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) \sin(\delta_b) \cos(\phi) + \sin(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) \sin(\phi) \right] $$

$$ Q_y(\phi) = R \left[ \cos(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) \sin(\delta_b) \sin(\phi) – \sin(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) \cos(\phi) \right] $$

$$ Q_z(\phi) = R \cos(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) \cos(\delta_b) $$

The parameter \( \phi \) ranges from 0 to \( \frac{\arccos\left( \frac{\cos(\delta_a)}{\cos(\delta_b)} \right)}{\sin(\delta_b)} \), where \( \delta_a \) is the tip cone angle. For the small-end spherical involute, the cone distance \( R \) is replaced by \( R – B \), where \( B \) is the face width of the straight bevel gear. Thus, the equations for the small-end are:

$$ Q_x(\phi) = (R – B) \left[ \cos(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) \sin(\delta_b) \cos(\phi) + \sin(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) \sin(\phi) \right] $$

$$ Q_y(\phi) = (R – B) \left[ \cos(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) \sin(\delta_b) \sin(\phi) – \sin(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) \cos(\phi) \right] $$

$$ Q_z(\phi) = (R – B) \cos(\phi \sin(\delta_b)) \cos(\delta_b) $$

To model both sides of the tooth, additional coordinate transformations are necessary. Introducing a secondary coordinate system \( S_2(x_2, y_2, z_2) \), rotated by an angle \( \theta \) about the z-axis, allows for symmetry. The angle \( \theta \) is composed of \( \theta_1 \), the angle between the starting point and the pitch cone, and \( \theta_2 \), which relates to the tooth thickness. Specifically, \( \theta_1 \) is calculated using vector dot products, and \( \theta_2 = \frac{\pi m}{4R \sin(\delta)} \), where \( m \) is the module at the large end and \( \delta \) is the pitch cone angle. The coordinates for the left-side spherical involute at the large end in \( S_2 \) are derived as:

$$ P_x(\phi) = Q_x(\phi) \cos(2\theta) + Q_y(\phi) \sin(2\theta) $$

$$ P_y(\phi) = Q_x(\phi) \sin(2\theta) – Q_y(\phi) \cos(2\theta) $$

$$ P_z(\phi) = Q_z(\phi) $$

Similarly, for the small end, \( R \) is substituted with \( R – B \). These equations form the basis for generating the precise tooth profiles of the straight bevel gear in a digital environment.

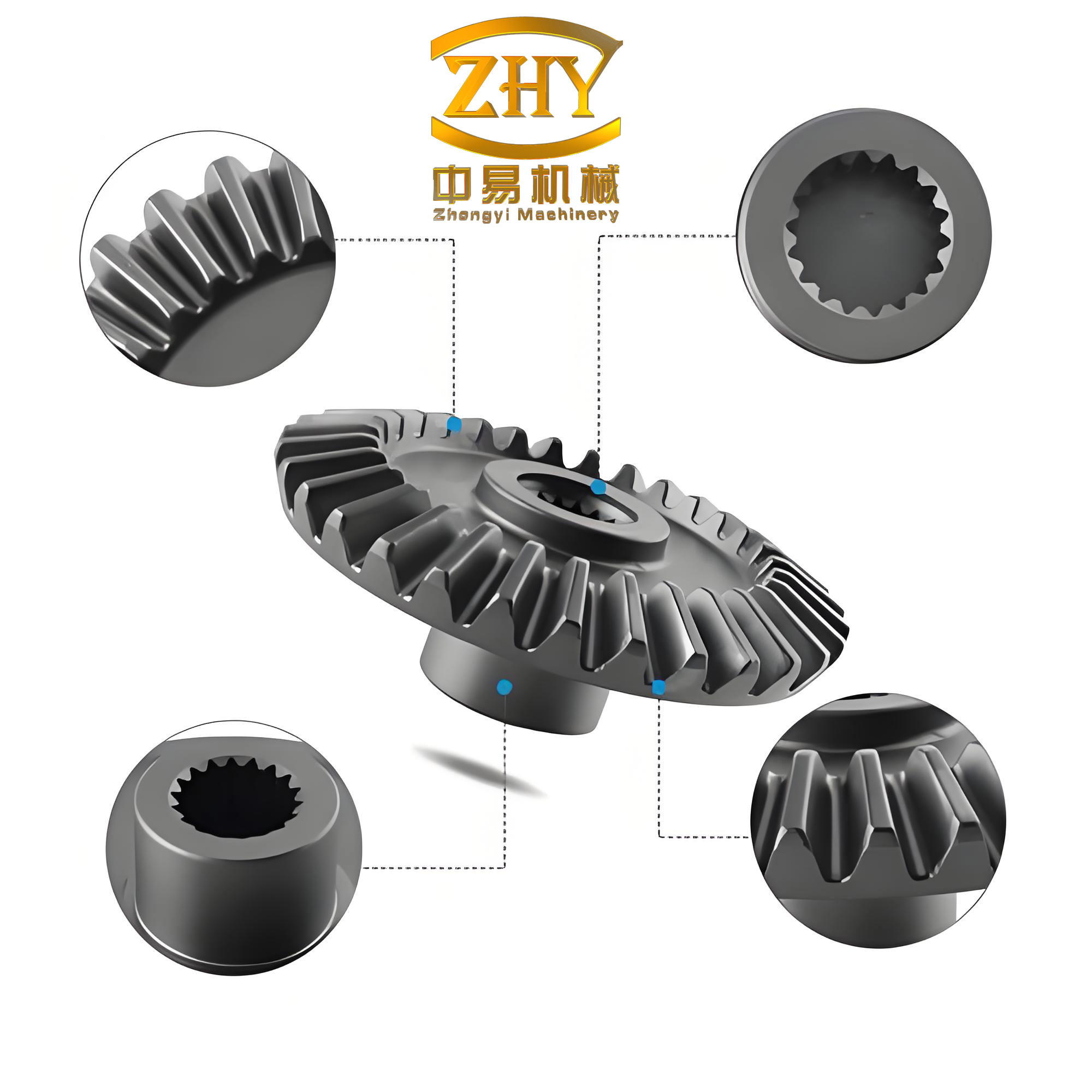

With the mathematical model established, the next step involves implementing it in SolidWorks to create a 3D model of the straight bevel gear. This process begins by discretizing the parameter \( \phi \) within its range and computing the coordinates for points on the spherical involute curves using software like MATLAB. The coordinates are saved in a text file and imported into SolidWorks via the “Curve Through XYZ Points” function. This generates the spherical involute curves for both the large and small ends of the gear tooth, as shown in the visualization below.

Once the curves are generated, the boundary surface method is applied to form the tooth surfaces. This involves using SolidWorks’ “Boundary Surface” tool to create surfaces between the large-end and small-end curves for each side of the tooth. The surfaces are then trimmed with circular arcs representing the tip circles at both ends to define the complete tooth profile. After forming the surfaces, the “Thicken” function converts them into a solid entity, representing a single tooth of the straight bevel gear. Finally, the “Circular Pattern” tool is used to array this tooth around the gear axis, resulting in the full gear model.

To illustrate the parameters involved in modeling a straight bevel gear, the following table summarizes key variables and their descriptions:

| Parameter | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Cone Distance | \( R \) | Distance from apex to large end |

| Face Width | \( B \) | Width of the gear tooth |

| Base Cone Angle | \( \delta_b \) | Angle of the base cone |

| Tip Cone Angle | \( \delta_a \) | Angle at the tooth tip |

| Module | \( m \) | Gear module at large end |

| Rotation Angle | \( \phi \) | Parameter for involute generation |

The advantages of this method for modeling straight bevel gears are numerous. Firstly, it eliminates approximations by using exact spherical involute equations, enhancing accuracy in gear design and simulation. Secondly, the process is parametric, allowing for easy modifications by adjusting key variables such as \( R \), \( B \), and \( \delta_b \). This makes it suitable for designing various straight bevel gears without starting from scratch. Additionally, integrating MATLAB with SolidWorks streamlines the curve generation, reducing manual errors and saving time. In practical applications, this approach can improve the performance of straight bevel gears in machinery, such as automotive differentials and industrial gearboxes, by ensuring precise tooth engagement and load distribution.

In conclusion, the boundary surface method in SolidWorks, supported by rigorous mathematical modeling, offers a reliable solution for 3D modeling of straight bevel gears. By deriving spherical involute curves and leveraging software tools, designers can achieve high precision and flexibility. This method not only addresses the limitations of traditional techniques but also promotes innovation in gear technology. As industries advance toward digitalization, such approaches will play a pivotal role in optimizing mechanical systems involving straight bevel gears. Future work could explore automation scripts or integration with other CAD platforms to further enhance efficiency.