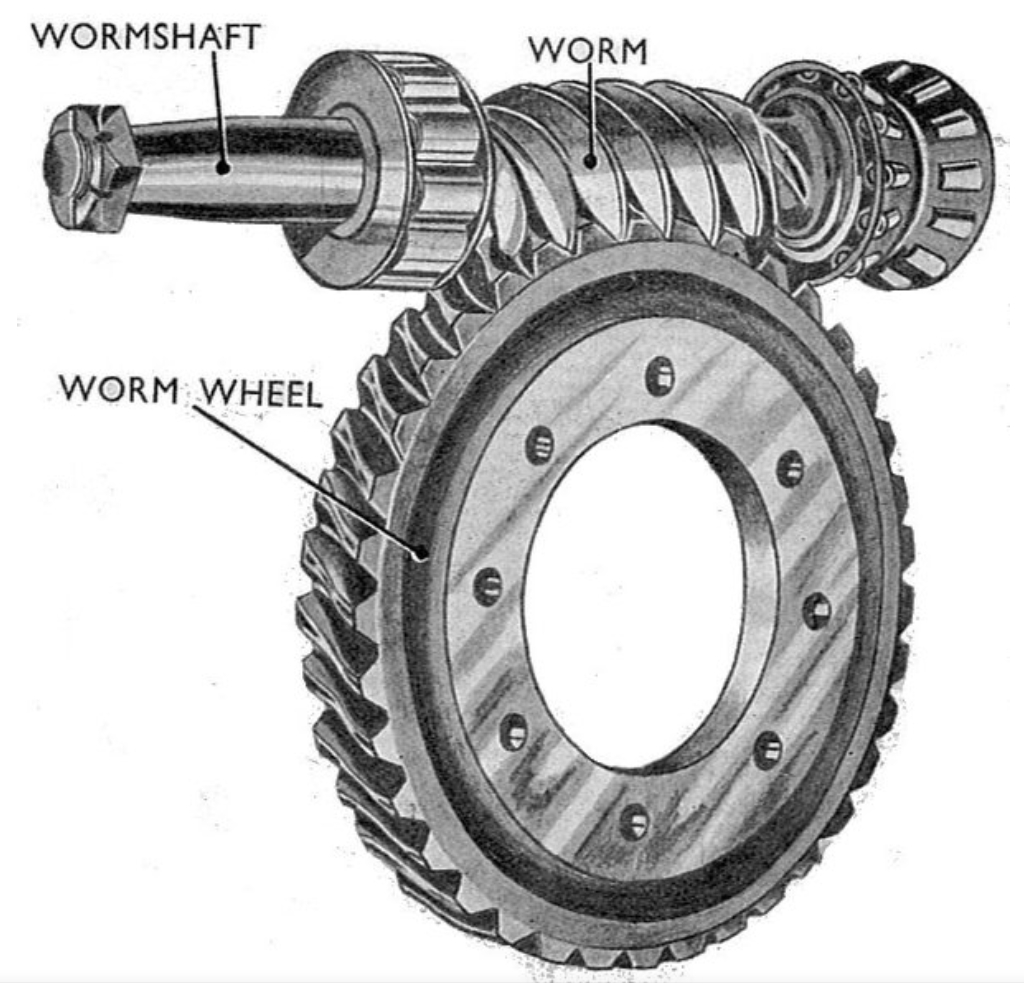

In the field of aviation, the Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) plays a critical role in providing independent compressed air, electrical power, and emergency energy to enhance flight safety. The worm gear mechanism used in APU air passage hatch cover actuators is a core component characterized by its compact size and high load-bearing capacity. Ensuring the reliability of this worm gear transmission is vital for APU operation. This study focuses on analyzing the performance of the worm gear in the actuator, with specific investigations into parametric modeling, contact stress simulation, temperature analysis, and modal analysis. The research aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the worm gear’s operational reliability under various conditions.

The worm gear tooth surface in APU applications is an irregular curved surface, and existing parametric modeling methods often fail to ensure high precision. We propose a novel parametric modeling approach for the worm gear tooth surface based on spatial meshing principles. By deriving parameter expressions for the tooth profile on the worm gear’s middle plane and its parallel planes, we use these profiles as baselines to generate the tooth surface through a cutting method. For the worm, the tooth surface is obtained by rotating a cutting tool profile to remove material. This method enables parametric, programmable, and high-precision modeling of the worm gear for APU use.

Using VB.net, we developed a parametric modeling plugin for the APU worm gear. Through data interaction with databases and 3D modeling software, the plugin automatically generates 3D models of the worm and worm gear based on specified parameters. We validated the correctness of the models by performing interference checks and motion transmission simulations on assemblies with different numbers of worm threads. The results confirmed that the models are accurate and suitable for further analysis.

Finite element simulations were conducted to analyze the contact stress between the worm and worm gear, as well as the strength of the worm shaft, under different wind conditions during APU air passage hatch cover opening and locking. The simulations were compared with theoretical calculations, and the effects of assembly errors, external force disturbances on the worm shaft, and lightweight treatment of the worm shaft on contact stress were investigated. Our findings indicate that conventional steel-copper (20CrMnTi-ZCuSn10Pb1) worm gear pairs do not meet contact strength requirements, whereas a new steel-steel (20CrMnTi-0Cr17Ni4Cu4Nb) pair satisfies these requirements.

For the new steel-steel worm gear material pair, we analyzed the temperature on the tooth surfaces during hatch cover driving. Experimental measurements of the friction coefficient for the material specimens were performed. The worm gear body temperature field was established, and the flash temperature during meshing was derived using Blok’s flash temperature theory. The maximum temperature between tooth surfaces during meshing was found to be below the failure temperature of the lubricating grease. Additionally, modal analysis of the worm gear and worm shaft revealed that their natural frequencies are significantly higher than the excitation frequencies, ensuring dynamic stability. This multi-faceted analysis verifies the operational reliability of the APU worm gear.

The spatial meshing principle of the worm gear is fundamental to understanding its kinematics and dynamics. We established coordinate systems for the worm and worm gear, including the tool coordinate system, worm coordinate system, and meshing coordinate system. Using coordinate transformation principles, we derived transformation matrices between these systems. Based on the spatial meshing theory and manufacturing principles, we developed parameter expressions for the worm gear tooth profile on the middle plane and parallel planes. The worm gear tooth surface equation in the worm gear coordinate system \( S_2 \) is given by:

$$ \begin{aligned}

x_2 &= l \cos \alpha_k \cos \theta \\

y_2 &= l \cos \alpha_k \sin \theta \\

z_2 &= -l \sin \alpha_k + p \theta

\end{aligned} $$

where \( l \) is the distance from a point on the tool edge to the origin, \( \alpha_k \) is the tool profile angle, \( \theta \) is the rotation angle, and \( p \) is the spiral parameter. The meshing equation is derived as:

$$ n \cdot v_{12} = 0 $$

where \( n \) is the normal vector on the worm surface and \( v_{12} \) is the relative velocity between the worm and worm gear. By applying boundary conditions and corrections, we obtained closed tooth profile curves for the worm gear, enabling precise parametric modeling.

For parametric modeling of the worm, we simulated the machining process using a trapezoidal tool profile. The worm blank is extruded into a cylinder, and the tool profile is sketched on the front plane. A helix is created on the side plane with a pitch equal to the worm lead. The tool profile is then swept along the helix to cut the worm teeth. For multi-start worms, a circular pattern is applied. The worm gear modeling involves sketching tooth profile curves on multiple parallel planes based on the derived parameter expressions. These curves are lofted to form the tooth surface, and a circular pattern creates the complete gear. This approach ensures accurate and parameterized models.

The modeling plugin, developed in VB.net, consists of a parameter input interface, database interaction, and control programs. The interface allows users to input structural parameters such as module, worm pitch diameter, number of starts, gear teeth, and pressure angle. The plugin checks parameter validity and calculates secondary parameters like transmission ratio and center distance. It generates 3D models in SolidWorks automatically. The plugin’s workflow includes opening SolidWorks, inputting parameters, and executing modeling commands. Control programs handle data validation, real-time updates, and API calls for SolidWorks operations. For example, to create a worm, the program selects planes, sketches circles, extrudes blanks, and performs sweep cuts. Validation through interference checks and motion simulations in Adams confirmed the models’ correctness, with stable transmission ratios observed.

Finite element analysis was performed using ANSYS Workbench to evaluate contact stress under different wind loads. The worm gear assembly was imported, and materials were defined with properties as shown in Table 1.

| Material | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Density (kg/m³) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worm (20CrMnTi) | 207 | 0.25 | 7800 |

| Worm Gear Steel (0Cr17Ni4Cu4Nb) | 191 | 0.27 | 7780 |

| Worm Gear Copper (ZCuSn10Pb1) | 116 | 0.34 | 8760 |

Tetrahedral meshing with refinement in the contact region was applied. Contact parameters included a friction coefficient of 0.11, augmented Lagrange method, and automatic time stepping. Loads were applied based on wind conditions, with torque values listed in Table 2 for hatch cover driving and locking.

| Condition | Gravity Torque | Wind Torque (4-level wind) | Rated Torque | Max Torque |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intake Driving | 2.00 | 14.20 | 16.20 | 24.30 |

| Exhaust Driving | 1.28 | 9.66 | 10.94 | 16.41 |

| Intake Locking | 2.00 | 14.20 | 26.40 | 39.60 |

| Exhaust Locking | 1.28 | 9.66 | 12.96 | 19.44 |

Simulation results showed that contact stress varies with meshing position, peaking at the entry and exit of engagement. For steel-steel pairs under 4-level wind, the maximum contact stress was 1113.36 MPa for driving and 1420.46 MPa for locking, whereas for steel-copper pairs, it was 982.63 MPa and 1257.79 MPa, respectively. Theoretical calculations using Hertzian contact theory yielded:

$$ \sigma_H = Z_E \sqrt{\frac{F_n}{L \rho_{\Sigma}}} $$

where \( Z_E \) is the elasticity factor, \( F_n \) is the normal load, \( L \) is the contact length, and \( \rho_{\Sigma} \) is the comprehensive curvature radius. The differences between simulation and theory were within 8%, validating the FEM approach. Factors like assembly errors (center distance, axial offset, and shaft angle) were analyzed, showing that contact stress increases with center distance error and has complex relationships with other errors. Lightweight treatment of the worm shaft by hollowing had minimal impact on contact stress but affected shaft stress. External disturbances altered contact stress, with downward and backward forces increasing it. Data fitting using BP neural networks for shaft angle error and contact stress provided accurate predictions, outperforming polynomial fits.

Temperature analysis involved friction coefficient measurements for the steel-steel material pair. Experiments used a ball-on-disk setup with loads corresponding to contact stresses. The average friction coefficient ranged from 0.105 to 0.118 under different lubricants. The worm gear body temperature field was modeled with the heat conduction equation:

$$ \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \frac{\lambda}{\rho c} \left( \frac{\partial^2 T}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 T}{\partial y^2} + \frac{\partial^2 T}{\partial z^2} \right) $$

For steady state, \( \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = 0 \). Convective heat transfer coefficients were calculated for different surfaces, and friction heat flux was derived as:

$$ q = \beta \alpha f P_n s_v $$

where \( \beta \) is the heat partition coefficient, \( \alpha \) is the energy conversion factor, \( f \) is the friction coefficient, \( P_n \) is the contact stress, and \( s_v \) is the sliding velocity. The maximum body temperature for intake driving was 36.844°C, and for exhaust driving, 34.344°C. Flash temperature during meshing was calculated using Blok’s theory:

$$ T_{flash} = \frac{\mu w_d (v_1 – v_2)}{2 \sqrt{\pi \lambda \rho c v}} $$

where \( \mu \) is the friction coefficient, \( w_d \) is the load per unit length, and \( v \) is the speed. The maximum flash temperatures were 60.71°C and 55.19°C for intake and exhaust, respectively, resulting in total temperatures below the grease failure temperature of 180°C. Modal analysis of the worm gear and shaft gave natural frequencies from 637.23 Hz to 7225.5 Hz, far exceeding typical excitation frequencies of 50-300 Hz, ensuring no resonance.

In conclusion, this research provides a comprehensive analysis of the APU worm gear, from parametric modeling to performance evaluation. The proposed modeling method and plugin facilitate accurate design, while FEM and experimental results validate the reliability under operational conditions. The steel-steel material pair is recommended for its superior contact strength and thermal performance. Future work could extend the modeling approach to other worm gear types and refine temperature predictions.