In mechanical engineering, the design and analysis of straight bevel gears are critical for transmitting motion and power between intersecting shafts, particularly in applications such as automotive systems, aerospace mechanisms, and industrial machinery. Traditional methods for generating tooth surfaces of straight bevel gears often rely on specific profiles like spherical involutes or circular arcs, which, while effective, limit the flexibility in gear design. These approaches typically involve complex geometric constructions and are not easily adaptable to arbitrary tooth profiles. To address this challenge, I propose a novel method based on the normal vector of the tooth surface, which provides a universal framework for generating and analyzing straight bevel gears with diverse tooth geometries. This method allows for direct computation of tooth surfaces by leveraging the direction angles and modulus of the normal vector, enabling active design and three-dimensional modeling without being constrained to predefined profiles. In this paper, I derive the mathematical foundations of this approach, illustrate its application through examples, and demonstrate its versatility in handling various tooth forms, including spherical involutes and polynomial-based profiles. The key advantage lies in its systematic and logical formulation, which simplifies the traditionally multi-choice problem of tooth surface generation for straight bevel gears.

The core of this method revolves around the concept of the tooth surface normal vector. Consider a point M on the tooth surface Σ of a straight bevel gear. The normal vector at M, denoted as \( \vec{l} \), extends from the node \( O_m \) on the pitch cone to M, with its length \( l = |\vec{l}| \) referred to as the normal line length. By establishing a coordinate system at \( O_m \) with axes aligned such that the \( z_m \)-axis is parallel to the gear axis and the \( y_m \)-axis is tangent to the pitch cone, the direction of the normal vector can be characterized by angles α, β, and γ. Specifically, the relationships \( \cos \alpha = \sin \beta \cos \lambda \) and \( \cos \gamma = -\sin \beta \sin \lambda \) hold, leading to the unit normal vector:

$$ \vec{n}_l = \begin{pmatrix} \sin \beta \cos \lambda \\ \cos \beta \\ -\sin \beta \sin \lambda \end{pmatrix}, $$

where \( 0 \leq \beta \leq \pi \), \( -\pi \leq \lambda \leq \pi \), and \( l \geq 0 \). The full normal vector is then expressed as \( \vec{l} = l \vec{n}_l \). This formulation serves as the foundation for generating the tooth surface by relating the normal vector parameters to the gear’s geometric variables.

To derive the tooth surface equation, coordinate transformations are employed. Let \( Oxyz \) and \( O_t x_t y_t z_t \) be fixed parallel coordinate systems separated by a distance \( u = OO_t \), while \( O_m x_m y_m z_m \) and \( O_n x_n y_n z_n \) are moving coordinate systems that remain coincident at their origins. During motion, the \( y_m \)-axis stays tangent to the pitch cone. The position vector of point M in the \( Oxyz \) system is given by:

$$ \vec{R}(\phi, u) = M(\phi)_{nm} \vec{l} + M(r)_{tn} + M(u)_{st}, $$

where \( M(\phi)_{nm} \) is the rotation matrix from \( O_m x_m y_m z_m \) to \( O_n x_n y_n z_n \), \( M(r)_{tn} \) is the translation matrix to \( O_t x_t y_t z_t \), and \( M(u)_{st} \) is the translation matrix to \( Oxyz \). These matrices are defined as:

$$ M_{nm} = \begin{bmatrix} \sin \phi & -\cos \phi & 0 \\ \cos \phi & \sin \phi & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad M_{tn} = \begin{bmatrix} r \sin \phi \\ r \cos \phi \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}, \quad M_{st} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ u \end{bmatrix}. $$

The unit normal vector in \( Oxyz \) is \( \vec{n} = M(\phi)_{nm} \vec{n}_l \). According to gear meshing theory, the conditions for proper tooth contact are \( \vec{R}’_\phi \cdot \vec{n} = 0 \) and \( \vec{R}’_u \cdot \vec{n} = 0 \), where primes denote partial derivatives. Solving these equations yields the differential relationships:

$$ \frac{dl}{d\phi} = r \cos \beta = u \tan \delta \cos \beta, $$

and

$$ \frac{dl}{du} = \sin \beta \frac{\cos \delta}{\sin(\lambda – \delta)}, $$

with the initial condition \( l_{\phi=0} = l_0 \). Here, \( \delta \) is the pitch cone angle. These equations establish the connections between the parameters \( \beta \), \( \lambda \), and \( l \) and the variables \( \phi \) and \( u \), enabling the generation of tooth surfaces by specifying functional relationships, such as \( l(\phi, u) \), \( \beta(\phi, u) \), or \( \lambda(\phi, u) \). This approach facilitates active design of straight bevel gears, allowing for customization beyond traditional profiles.

To illustrate the applicability of this method, I first consider the case of a spherical involute straight bevel gear. The spherical involute profile is defined by the relations \( \psi = \phi \sin \delta_b \) and \( l = \frac{u}{\cos \delta} \sin(\phi \sin \delta_b) \), where \( \delta_b \) is the base cone angle. Substituting into the differential equations gives:

$$ \cos \beta = \frac{\sin \delta_b}{\sin \delta} \cos(\phi \sin \delta_b), $$

and

$$ \sin(\lambda – \delta) = \frac{\sin(\phi \sin \delta_b)}{\sin \beta}. $$

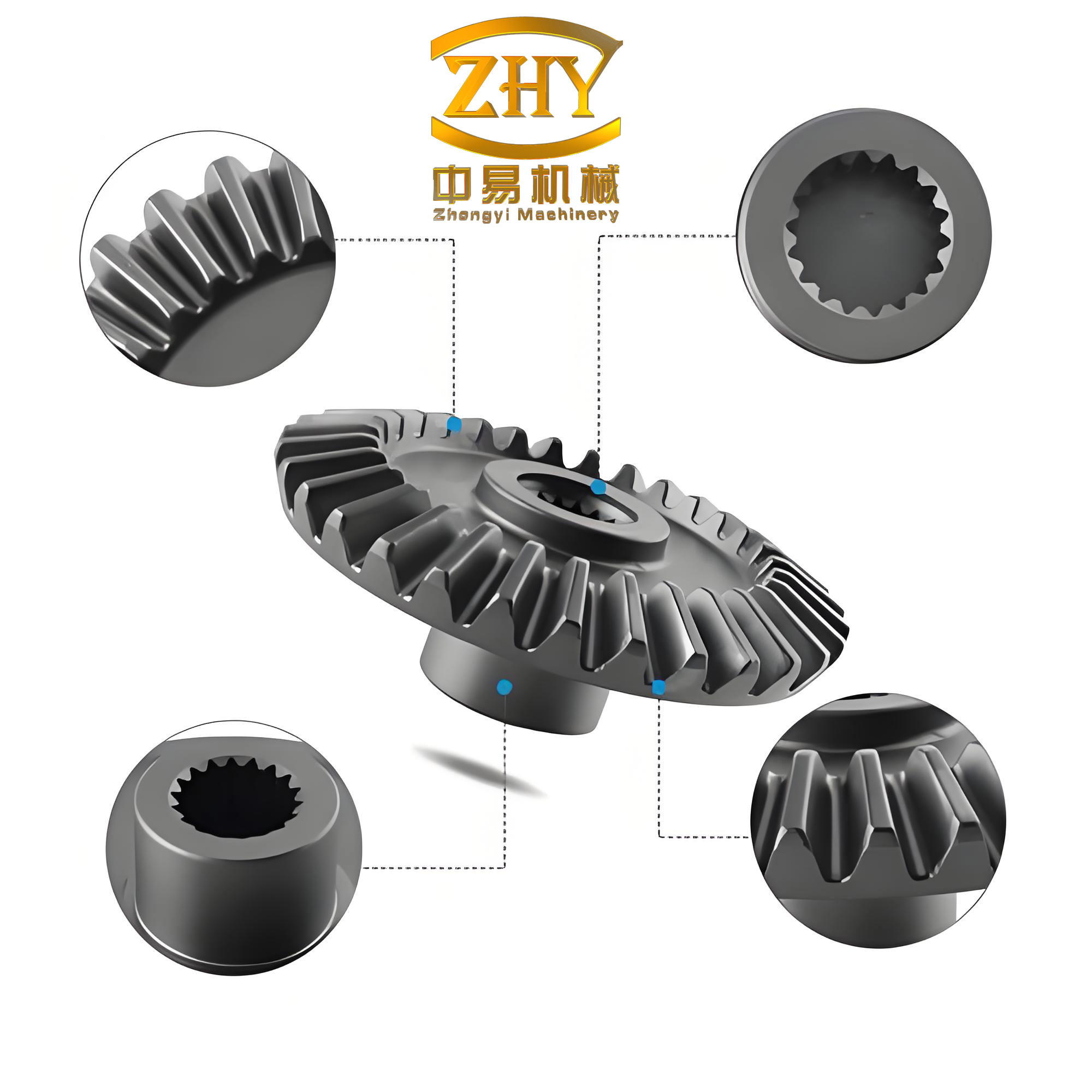

Using these in the position vector equation yields the tooth surface. For example, with a pressure angle \( \alpha_0 = \pi/9 \), pitch cone angle \( \delta = 5\pi/36 \), and tooth number \( z = 18 \), the generated straight bevel gear exhibits the characteristic spherical involute geometry. This demonstrates how the normal vector method seamlessly handles classic profiles.

For a more general case, I explore a straight bevel gear with a tooth surface defined by a bivariate polynomial in the direction angle \( \beta \). Let \( \beta(\phi, u) = a_0 + a_1 u + a_2 \phi + a_3 u \phi \), where \( a_0, a_1, a_2, a_3 \) are constants. With \( \delta = 5\pi/36 \) and \( z = 18 \), different coefficient sets produce distinct tooth shapes. For instance, setting \( a_0 = 0.349 \), \( a_1 = a_2 = a_3 = 0 \) gives a constant \( \beta \), while \( a_0 = 0.349 \), \( a_1 = 0.01 \), \( a_2 = a_3 = 0 \) results in a linear variation with \( u \), and \( a_0 = 0.349 \), \( a_2 = 0.3 \), \( a_1 = a_3 = 0 \) gives a linear variation with \( \phi \). The table below summarizes the parameter effects on tooth geometry for straight bevel gears:

| Coefficient Set | β Function | Tooth Shape Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| a₀=0.349, a₁=a₂=a₃=0 | β = 0.349 | Uniform tooth profile along both φ and u |

| a₀=0.349, a₁=0.01, a₂=a₃=0 | β = 0.349 + 0.01u | Linear change along axial direction, altering tooth thickness |

| a₀=0.349, a₂=0.3, a₁=a₃=0 | β = 0.349 + 0.3φ | Linear change along angular direction, affecting tooth curvature |

This flexibility underscores the method’s capacity for active design, enabling engineers to tailor straight bevel gears for specific performance requirements. The normal vector approach transforms the tooth surface generation into a controllable process, where modifying the direction angle function directly influences the gear’s mechanical properties, such as contact patterns and load distribution.

In addition to the polynomial example, the method can be extended to other functional forms. For instance, specifying \( l(\phi, u) \) as an exponential or trigonometric function allows for advanced tooth profiles that optimize noise reduction or efficiency. The key equations remain the same, with the differential relations guiding the integration. To further illustrate, consider a scenario where \( l = u e^{-k\phi} \cos(\phi) \) for a straight bevel gear, with \( k \) as a damping constant. Substituting into the differential equations and solving for \( \beta \) and \( \lambda \) would yield a tooth surface with decaying oscillations, potentially useful in vibration-sensitive applications. The table below compares different functional choices for straight bevel gear design:

| Functional Form | Key Equations | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Spherical Involute | $$ l = \frac{u}{\cos \delta} \sin(\phi \sin \delta_b) $$ | Standard gears with smooth meshing |

| Bivariate Polynomial | $$ \beta = a_0 + a_1 u + a_2 \phi + a_3 u \phi $$ | Customized gears for load optimization |

| Exponential-Trigonometric | $$ l = u e^{-k\phi} \cos(\phi) $$ | Gears with enhanced damping properties |

The mathematical rigor of this method ensures that all generated surfaces satisfy the fundamental conditions of gear meshing theory. By working directly with the normal vector, I avoid the limitations of profile-specific approaches, providing a unified framework that accommodates any tooth form. This is particularly beneficial for modern straight bevel gear applications, where demands for efficiency and customization are ever-increasing. For example, in automotive differentials, the ability to design tooth surfaces that minimize friction losses can lead to significant energy savings. Similarly, in aerospace, tailored straight bevel gears can reduce weight while maintaining strength.

In conclusion, the normal vector-based method for generating tooth surfaces of straight bevel gears offers a versatile and powerful tool for gear design. By leveraging the direction angles and modulus of the normal vector, I enable direct computation and active control over tooth geometry, surpassing the constraints of traditional methods. The examples presented—ranging from spherical involutes to polynomial-based profiles—demonstrate the method’s broad applicability and its potential to revolutionize the design and modeling of straight bevel gears. Future work could explore integration with computational tools for real-time simulation and optimization, further expanding the horizons of gear engineering. This approach not only simplifies the complex problem of tooth surface generation but also opens new pathways for innovation in mechanical transmission systems, ensuring that straight bevel gears continue to meet the evolving needs of industry.