In mechanical transmission systems, straight bevel gears are widely used to transmit motion and power between intersecting shafts. These gears offer advantages such as simple design, ease of manufacturing, and the ability to change transmission direction, making them prevalent in automotive, aerospace, and engineering machinery applications. However, straight bevel gears are prone to issues like impact, noise, and unstable transmission due to the sudden engagement of teeth along the tooth width and fewer teeth in simultaneous contact. Under high-speed conditions, failure modes often result from contact stress-induced fatigue pitting, which is challenging to calculate accurately using theoretical formulas. Therefore, dynamic simulation tools are essential for analyzing contact stress variations and improving gear design and durability.

To address these challenges, we developed a parametric design approach for straight bevel gears using Creo software. This method establishes relationships among key design parameters, enabling efficient modeling and modification. The basic parameters of the straight bevel gears studied in this work are summarized in Table 1. These parameters include tooth number, module, pressure angle, and cone angles, which are critical for defining the gear geometry and ensuring proper meshing.

| Parameter | Pinion | Gear |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth | 17 | 35 |

| Module (mm) | 3 | 3 |

| Normal Pressure Angle | 25° | 25° |

| Pitch Cone Angle | 31°41’59” | 58°18’1″ |

| Face Cone Angle | 34°34’24” | 61°34’40” |

| Root Cone Angle | 27°48’28” | 54°48’50” |

| Cone Distance (mm) | 51.17 | 51.17 |

| Tooth Width (mm) | 12 | 12 |

The involute tooth profile is employed for its advantages in maintaining constant transmission ratio and smooth motion. In Creo, we defined the spherical involute curve equations to generate precise tooth profiles. The spherical involute equations are given by:

$$ R = \rho $$

$$ \theta = \delta_f + (\delta_a – \delta_f) \times t $$

$$ \phi = \left( \frac{1}{\sin \delta_b} \right) \arccos \left( \frac{\cos \delta}{\cos \delta_b} \right) – \arccos \left( \frac{\tan \delta_b}{\tan \delta} \right) $$

where \( R \) is the outer cone distance, \( \delta_f \) is the root cone angle, \( \delta_a \) is the face cone angle, \( \delta_b \) is the base cone angle, and \( t \) ranges from 0 to 1. Using these equations, we created reference curves for the large and small ends of the straight bevel gear, including the addendum circle, pitch circle, and dedendum circle. The spherical involute curves were generated from the equation-driven feature in Creo, as illustrated in the modeling process.

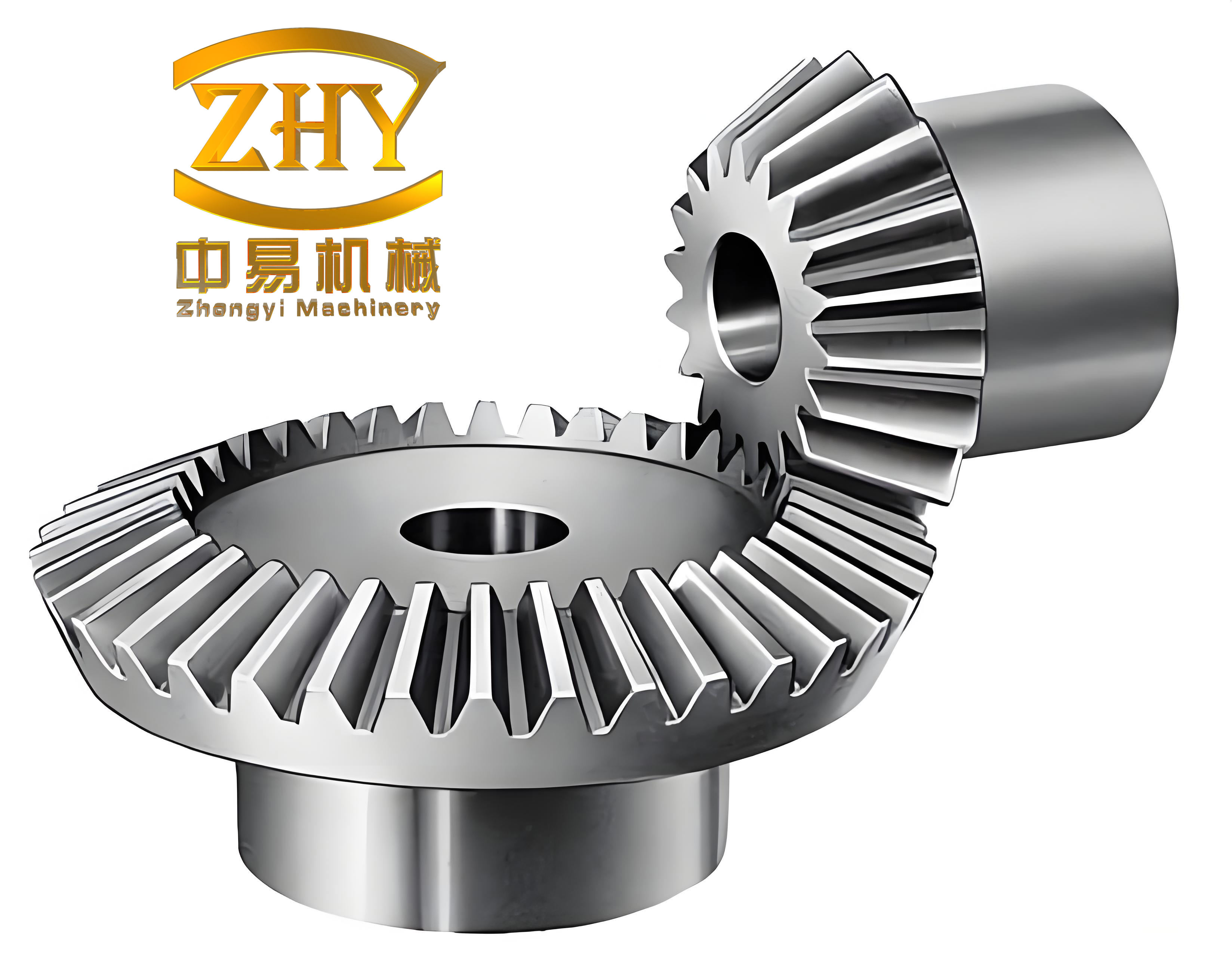

To form the tooth entity, we used the sweep blend feature in Creo. The sweep trajectory was defined along the tooth length, and cross-sections were sketched at both ends based on the involute profiles. After creating the first tooth, it was replicated and rotated, followed by pattern arraying to generate all teeth. The gear blank and other features were parameterized by embedding dimensions in Creo’s relation parameters, allowing for quick modifications. This parametric approach facilitates the design of various straight bevel gear configurations, such as the pinion and gear pair, by simply adjusting input parameters. The assembled straight bevel gear model was checked for interference in Creo’s mechanism module, ensuring zero interference and proper meshing.

For dynamic analysis, we imported the straight bevel gear model into RecurDyn, a multibody dynamics software. The contact force model in RecurDyn uses the penalty method, which converts contact nonlinearities into material nonlinearities. According to Hertz theory, the normal contact force \( F_n \) is calculated as:

$$ F_n = k \delta^{m_3} + c \dot{\delta} \delta^{m_1} \delta^{m_2} $$

where \( k \) is the contact stiffness coefficient, \( \delta \) is the normal penetration depth, \( c \) is the contact damping coefficient, \( \dot{\delta} \) is the relative velocity at the contact point, and \( m_1 \), \( m_2 \), and \( m_3 \) are nonlinear exponents. The stiffness coefficient \( k \) is derived from Hertz contact theory:

$$ k = \frac{4}{3} \sqrt{ \frac{R_1 R_2}{R_1 + R_2} } \frac{1}{ \frac{1 – \nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \nu_2^2}{E_2} } $$

where \( R_1 \) and \( R_2 \) are the radii of curvature at the contact point, \( E_1 \) and \( E_2 \) are the elastic moduli, and \( \nu_1 \) and \( \nu_2 \) are the Poisson’s ratios. For the straight bevel gear simulation, we set the material properties as follows: Young’s modulus \( E = 2.06 \times 10^5 \) MPa, Poisson’s ratio \( \nu = 0.3 \), and density \( \rho = 7800 \) kg/m³. The friction coefficient was set to 0.1, maximum penetration depth to 0.01, and nonlinear exponents \( m_1 = 1.6 \), \( m_2 = 1 \), \( m_3 = 2 \), with stiffness coefficient \( k = 10,000 \) and damping coefficient \( c = 1 \).

The dynamic simulation was configured with a pinion rotational speed of 1500 rpm, corresponding to an angular velocity \( \omega = \frac{2 \pi n}{60} = 157 \) rad/s. The gear ratio is 17:35, so the theoretical gear speed is \( n_{\text{gear}} = n_{\text{pinion}} \times \frac{17}{35} = 750 \) rpm. In RecurDyn, we applied a rotational joint to both gears and defined contact pairs. The pinion was driven by a speed function \( 157 \times \text{STEP}(\text{TIME}, 0, 0, 1, 1) \) to gradually reach full speed in 1 second, minimizing initial impact. The gear was subjected to a torque load function \( -X \times \text{STEP}(\text{TIME}, 0, 0, 1, 1) \), where \( X \) represents the load magnitude in N·mm, increased gradually to avoid sudden shocks. Simulations were run for 5 seconds with a step size of 500 and plot multiplier step factor of 5.

We analyzed the dynamic behavior of the straight bevel gears under different load conditions: 0 N·mm, 50 N·mm, 250 N·mm, and 500 N·mm. The rotational speeds of both gears were monitored to verify model accuracy. Under no load, the pinion speed stabilized at 157 rad/s, while the gear speed oscillated around the theoretical value of 76.257 rad/s due to meshing dynamics. As load increased, speed fluctuations became more frequent and pronounced, indicating the influence of torque on system stability. For instance, at 500 N·mm load, the gear speed showed higher variability, as summarized in Table 2.

| Load (N·mm) | Pinion Speed (rad/s) | Gear Speed (rad/s) | Fluctuation Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 157 ± 0.5 | 76.257 ± 0.3 | Minor oscillations |

| 50 | 157 ± 0.6 | 76.257 ± 0.4 | Increased variability |

| 250 | 157 ± 0.7 | 76.257 ± 0.5 | Pronounced fluctuations |

| 500 | 157 ± 0.8 | 76.257 ± 0.6 | High frequency oscillations |

The primary focus was on contact stress analysis during meshing. The dynamic contact stress was extracted from the simulation results, revealing how stress varies with load. At no load, the maximum contact stress reached 2636.6 N during the initial engagement phase (0–1 second), due to impact forces. As load increased, the contact stress magnitude and distribution changed significantly. For example, at 50 N·mm load, the maximum stress was 2850 N, while at 500 N·mm, it peaked at 3500 N. The contact stress over time for different loads is summarized in Table 3, highlighting the stress values and their implications for fatigue life.

| Load (N·mm) | Maximum Contact Stress (N) | Time of Occurrence (s) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2636.6 | 0.5 | Initial impact peak |

| 50 | 2850.0 | 1.2 | Steady-state stress increase |

| 250 | 3200.0 | 2.0 | Moderate load effects |

| 500 | 3500.0 | 3.5 | High load, sustained stress |

The variation in contact stress can be modeled using the Hertzian contact theory, where the maximum contact pressure \( p_{\text{max}} \) for two curved surfaces is given by:

$$ p_{\text{max}} = \frac{3F_n}{2 \pi a b} $$

with the semi-axes \( a \) and \( b \) of the contact ellipse calculated as:

$$ a = \alpha \sqrt[3]{ \frac{3F_n R_e}{2E_e} }, \quad b = \beta \sqrt[3]{ \frac{3F_n R_e}{2E_e} } $$

where \( R_e = \sqrt{R_1 R_2} \) is the equivalent radius, \( E_e = \frac{1}{\frac{1-\nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1-\nu_2^2}{E_2}} \) is the equivalent modulus, and \( \alpha \) and \( \beta \) are coefficients dependent on the geometry. For straight bevel gears, the curvature radii change during meshing, leading to dynamic stress variations. Our simulation results show that higher loads amplify these stresses, increasing the risk of pitting and fatigue failure.

In discussion, the parametric design of straight bevel gears in Creo enables rapid prototyping and optimization, while RecurDyn simulations provide insights into dynamic behavior. The contact stress analysis under different loads reveals that stress concentrations occur at specific meshing points, influenced by tooth geometry and load conditions. This study demonstrates that multibody dynamics simulation is a powerful tool for predicting gear performance and durability, especially for straight bevel gears operating under high-speed conditions. The findings can guide design improvements to reduce stress and enhance gear life.

In conclusion, we have presented a comprehensive approach for modeling and simulating straight bevel gears using Creo and RecurDyn. The parametric design facilitates efficient gear generation, and the dynamic analysis captures contact stress variations under different loads. This work provides a feasible dynamics foundation for further studies on vibration and impact in straight bevel gears, contributing to better design and reliability in practical applications.