In mechanical engineering, straight bevel gears are widely used for transmitting motion and power between intersecting shafts due to their relatively simple design and manufacturing processes. The concavity and convexity of the tooth surface play a critical role in machining methods, such as generating planing, which relies on simulating gear meshing motions to envelope the tooth surface. Understanding the geometric properties of the straight bevel gear tooth surface is essential for optimizing manufacturing techniques and ensuring performance. In this article, I propose a vector-based approach to analyze the concavity and convexity of the straight bevel gear tooth surface. By examining the variation of tangent vectors along spherical involutes on the tooth surface, I indirectly reflect the surface’s convex characteristics. This method leverages mathematical modeling and vector analysis to provide a straightforward and computationally efficient solution.

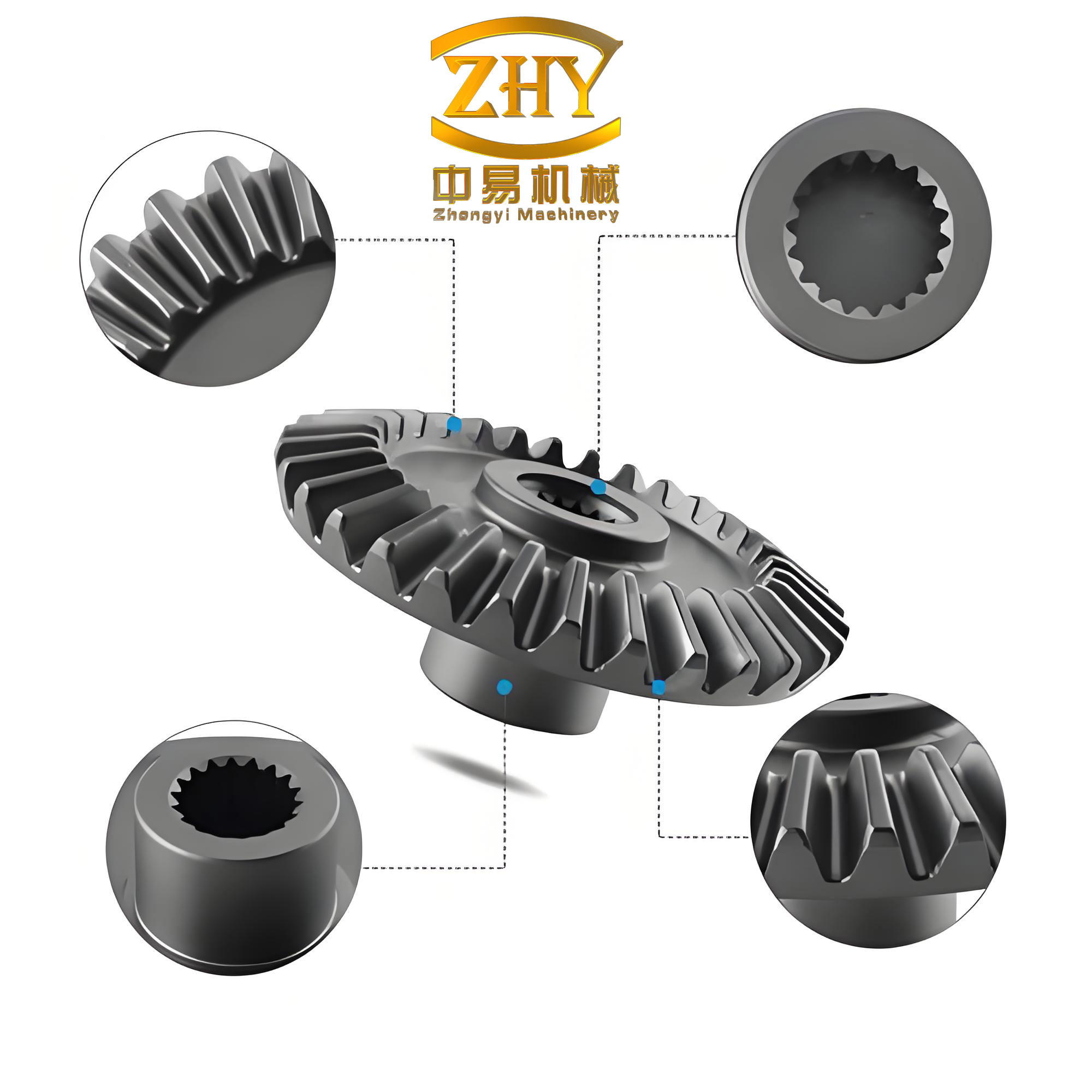

The formation principle of the straight bevel gear tooth surface differs significantly from that of spur gears. While spur gear tooth surfaces are generated by sweeping a planar involute along the axis of a cylinder, the straight bevel gear tooth surface is derived from a spherical involute. Specifically, a generating plane with a radius equal to the base cone distance rotates around the base cone while maintaining tangency. As it rolls without slipping, the tangent line sweeps out a surface known as the involute cone, which constitutes the theoretical tooth surface of the straight bevel gear. When a spherical surface centered at the cone apex with a radius equal to the cone distance intersects this involute cone, it forms a spherical involute. The entire tooth surface can be considered as composed of multiple spherical involutes with varying radii, as illustrated below.

To mathematically model the straight bevel gear tooth surface, I treat it as a ruled surface, which is defined by a family of straight lines. A ruled surface can be expressed in two forms: one using a directrix curve and a direction vector, and another using two boundary curves. For the straight bevel gear, I employ the latter representation, where the large-end and small-end spherical involutes serve as the boundary curves. The tooth surface is then generated by linearly interpolating between these curves. The coordinate systems involved in this derivation include a fixed coordinate system S(x, y, z) centered at the cone apex O, with the z-axis aligned along the base cone axis, and an auxiliary moving coordinate system S1(x1, y1, z1) that rotates with the generating plane. The relationship between these systems facilitates the derivation of the tooth surface equations.

The parametric equations for a point on the large-end spherical involute in the fixed coordinate system are derived as follows. Let R be the cone distance, δb be the base cone angle, and φ be the rotation angle parameter. The coordinates Q(φ) for any point on the large-end involute are given by:

$$ Q_x(φ) = R[\cos(φ \sin δ_b) \sin δ_b \cos φ + \sin(φ \sin δ_b) \sin φ] $$

$$ Q_y(φ) = R[\cos(φ \sin δ_b) \sin δ_b \sin φ – \sin(φ \sin δ_b) \cos φ] $$

$$ Q_z(φ) = R \cos(φ \sin δ_b) \cos δ_b $$

Similarly, for the small-end spherical involute, where the radius is R – B (with B being the gear width), the coordinates W(φ) are obtained by substituting R with R – B in the above equations. Thus, the tooth surface S(r, φ) can be represented as a ruled surface:

$$ S(r, φ) = (1 – r) W(φ) + r Q(φ) $$

where r is a parameter ranging from 0 to 1, representing the position along the straight line between the small-end and large-end curves. This formulation allows for a comprehensive analysis of the straight bevel gear tooth surface geometry.

To analyze the concavity and convexity of the straight bevel gear tooth surface, I focus on the tangent vectors derived from the surface parameters. The partial derivatives of S(r, φ) with respect to r and φ yield the tangent vectors in the respective directions. The vector in the r-direction, Sr, is constant along a given generating line, indicating that the concavity does not vary along this direction. Therefore, the key to assessing concavity lies in the behavior of the tangent vector in the φ-direction, Sφ. This vector is computed as:

$$ S_φ = \frac{\partial S(r, φ)}{\partial φ} = (1 – r) W'(φ) + r Q'(φ) $$

Given that W(φ) is proportional to Q(φ), as shown by W(φ) = (R – B)/R Q(φ), Sφ simplifies to:

$$ S_φ = \left[ (1 – r) \frac{R – B}{R} + r \right] Q'(φ) $$

where Q'(φ) is the derivative of Q(φ) with respect to φ. The vector Q'(φ) has components that can be projected onto a plane to analyze its directional changes. By projecting Sφ onto the x1-y1 plane in the auxiliary coordinate system, I examine the angle η between the projection and the x1-axis. The cosine of this angle is given by:

$$ \cos η = \frac{Q_x'(φ)}{\sqrt{(Q_x'(φ))^2 + (Q_y'(φ))^2}} $$

Differentiating cos η with respect to φ reveals the monotonicity of this function. The derivative is expressed as:

$$ \frac{d(\cos η)}{dφ} = \frac{R^3 \sin^3(φ \sin δ_b) \sin φ (\sin^2 δ_b – 1)^3}{\left[ (Q_x'(φ))^2 + (Q_y'(φ))^2 \right]^{3/2}} $$

Since sin²δb < 1, the numerator is negative, and the denominator is positive, resulting in d(cos η)/dφ < 0. This indicates that cos η is a monotonically decreasing function of φ, meaning that as φ increases, the angle η increases. This consistent directional change in the tangent vector projection implies that the straight bevel gear tooth surface is convex. In other words, all tangent planes along the generating lines lie on the same side of the surface, confirming its convex nature.

To further illustrate the properties of the straight bevel gear tooth surface, I summarize key parameters and their relationships in the following tables. These tables provide a clear overview of the geometric and mathematical aspects involved in the analysis.

| Parameter | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Cone Distance | R | Radius from cone apex to large end |

| Gear Width | B | Width of the gear tooth along the cone |

| Base Cone Angle | δb | Angle of the base cone |

| Rotation Angle | φ | Parameter for generating plane rotation |

| Interpolation Parameter | r | Parameter along generating line (0 to 1) |

| Vector | Expression | Role in Concavity Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Sr | Q(φ) – W(φ) | Constant along generating line, no concavity variation |

| Sφ | [(1 – r)(R – B)/R + r] Q'(φ) | Determines concavity through directional changes |

| Q'(φ) | Derivative of Q(φ) with respect to φ | Base vector for tangent direction analysis |

The vector-based method for judging concavity and convexity offers several advantages. It simplifies the complex geometric analysis of the straight bevel gear tooth surface by focusing on tangent vector behavior. This approach reduces computational effort and provides clear insights into surface properties. In practical applications, such as machining and design optimization, this method can aid in selecting appropriate tools and processes. For instance, in generating planing, knowing that the tooth surface is convex ensures that the tool path effectively envelopes the surface without undercutting or interference. Additionally, this method can be extended to other types of gears or surfaces where ruled surface representations are applicable.

In conclusion, I have presented a vector-based approach to determine the concavity and convexity of the straight bevel gear tooth surface. By modeling the surface as a ruled surface and analyzing the tangent vectors, I demonstrated that the surface is convex. The monotonic decrease in the cosine of the projection angle confirms this property. This method is efficient and relies on fundamental mathematical principles, making it suitable for engineering applications. Future work could involve applying this approach to skewed or modified straight bevel gears, or integrating it with computer-aided design systems for real-time analysis. The straight bevel gear remains a vital component in power transmission, and understanding its geometric characteristics is crucial for advancing manufacturing technologies.