In the automotive industry, the transmission system plays a critical role, and the gear shaft is a key component that demands high precision in manufacturing. As an engineer involved in machining processes, I have encountered numerous challenges in turning gear shafts for transmissions. This article details my firsthand experience in analyzing and resolving issues related to turning automotive gear shafts, focusing on fixture selection, temperature effects, tool wear, and measurement stability. The goal is to achieve high process capability indices, such as Cmk ≥ 1.67, through continuous improvement in a production environment.

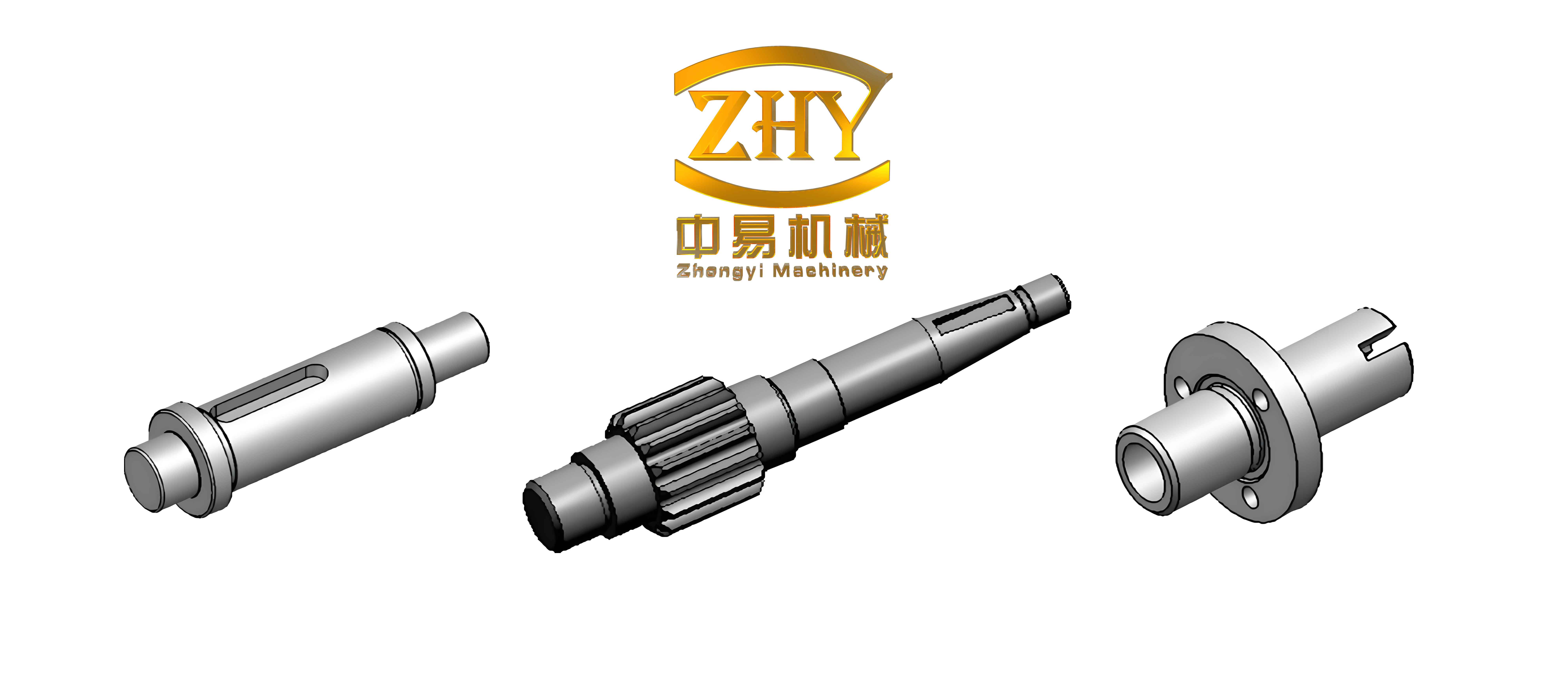

The gear shaft in question requires turning of all external dimensions except for the end faces and holes, with tight tolerances on radial runout relative to the center holes. Key dimensions include diameters and axial lengths, where errors in the X-axis can amplify radial inaccuracies. To meet these demands, we conducted a comprehensive analysis from multiple perspectives: human factors, machine equipment, materials, methods, environment, and measurement. This holistic approach ensured that we addressed all potential variables affecting the machining of the gear shaft.

One of the primary challenges was selecting an appropriate fixture for the gear shaft machining. We evaluated three different fixture schemes to ensure optimal clamping and precision. The first scheme involved using a hydraulic chuck for rough turning and a two-center method for finish turning, but this led to part deformation due to rigid positioning and varying blank materials. The second scheme incorporated compensating chucks like floating or pull-back chucks to correct for misalignment, but it did not meet the customer’s requirements for cycle time and machine count. The third scheme, which we ultimately adopted, utilized a center-driven chuck that combined semi-finish and finish turning in a single setup. This chuck features a dual-piston hydraulic cylinder and a drive center that allows for high clamping force during roughing and precise center-driven finishing, reducing cycle time and improving efficiency. The table below summarizes the comparison of these fixture schemes for the gear shaft.

| Fixture Scheme | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1: Hydraulic Chuck with Two Centers | Rough turning with one clamp and one center, finish with two centers | Simple setup | Part deformation, vibration issues |

| Scheme 2: Compensating Chucks | Floating or pull-back chucks for roughing, two centers for finishing | Better alignment correction | Longer cycle time, higher machine count |

| Scheme 3: Center-Driven Chuck | Single setup with switch between clamping and center-driven modes | Reduced cycle time, high precision | Higher cost, complex structure |

After implementing the center-driven chuck, we proceeded to test the machining process. However, initial results showed a Cm of 1.55 and Cmk of 0.48, indicating instability. The diameter dimensions of the gear shaft exhibited an abnormal trend starting from the 12th part, with a noticeable decline until the 31st part, after which they stabilized. This pattern did not align with typical tool wear behavior, prompting us to investigate temperature effects on the machine tool. The X-axis of the CNC lathe used a single-support ball screw structure, which was susceptible to thermal expansion causing zero-point drift. As the machine warmed up, the screw elongated, leading to positioning errors that doubled in the radial direction due to the gear shaft’s geometry.

To quantify this, we measured the temperature at the screw bearing housing using an infrared thermometer and recorded positioning accuracy with a laser interferometer. Data was collected at temperatures of 20.0°C, 23.1°C, and 27.8°C, with the screw travel ranging from 0 mm (fixed end) to 150 mm (free end). The positioning error at 150 mm decreased from -14.4 μm at 20.0°C to -0.7 μm at 27.8°C, demonstrating that higher temperatures reduced errors as the system reached thermal equilibrium. The relationship between temperature and positioning error can be modeled linearly for small ranges, but we used empirical data for compensation. The following table shows the recorded data points.

| Temperature (°C) | Screw Travel (mm) | Positioning Error (μm) |

|---|---|---|

| 20.0 | 150 | -14.4 |

| 23.1 | 150 | -9.0 |

| 27.8 | 150 | -0.7 |

We installed a temperature sensor on the bearing housing and connected it to the CNC system for real-time compensation. By inputting the data into the control software, we simulated a “positioning error compensation” curve that adjusted the X-axis dynamically. This approach minimized warm-up time and stabilized accuracy quickly. After applying temperature compensation, we repeated the turning tests on the gear shaft. The Cmk improved to 1.63, but a gradual upward trend in diameter dimensions indicated tool wear effects. This reinforced the need to address tool wear systematically, as it directly impacts the gear shaft quality.

Tool wear is inevitable in continuous machining, and for a gear shaft, even a small wear amount Δ on the tool results in a 2Δ increase in diameter due to the rotary nature of turning. We conducted tests with new inserts and monitored the diameter dimensions over 60 parts. The data showed relative stability in the first 11 parts, a sharp increase from the 11th to 20th parts, and a steady rise thereafter. This pattern conforms to typical tool wear curves, which can be approximated by a linear function for compensation purposes. We grouped the data into sets, calculated the slope k = Δy/Δx, where Δy is the change in diameter and Δx is the change in part number, and derived a fitted line equation: $$ y = kx + Q $$ where Q is the average diameter. The symmetric function of this line was then programmed into the CNC system using a macro for automatic compensation.

The logic for tool wear compensation involved several steps: start machining and record data; monitor for size changes; if changes occur, begin counting parts; after reaching a set number, stop machining; measure parts in a controlled environment; analyze data to compute the compensation function; and input the macro program. The macro program used variables such as part count and offset adjustments to apply corrections dynamically. For example, the macro code included instructions to check if the part number exceeded a threshold and then adjust the tool offset accordingly. This ensured that the gear shaft dimensions remained within tolerance without manual intervention.

To illustrate, consider the tool wear data for a batch of gear shafts. We recorded diameter measurements and fitted a linear model. Suppose the slope k is calculated as 0.001 mm per part, and the average diameter Q is 31.78 mm. The compensation function would be: $$ y = -0.001x + 31.78 $$ which is applied in reverse to counteract the wear. The following table provides a sample of the data used for analysis.

| Part Number | Diameter (mm) | Compensation Applied (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31.780 | 0 |

| 2 | 31.781 | 0 |

| … | … | … |

| 11 | 31.790 | 0 |

| 12 | 31.792 | -0.001 |

| 13 | 31.793 | -0.002 |

After implementing the macro compensation, we achieved a Cm of 1.83 and Cmk of 1.76, exceeding the required 1.67. The average diameter was 31.780367 mm, with minima and maxima within acceptable limits. This demonstrates the effectiveness of combining temperature and tool wear compensations for high-stability machining of gear shafts. It is important to note that other factors, such as blank consistency, fixture precision, and environmental controls, also contribute to overall performance, but temperature and tool wear are the dominant variables in this context.

In conclusion, through iterative analysis and adjustment, we successfully addressed the challenges in turning automotive gear shafts. The integration of advanced fixtures, real-time temperature compensation, and predictive tool wear macros enabled us to achieve superior process capability. This experience underscores the importance of a systematic approach in precision machining, where multiple factors must be harmonized to produce high-quality gear shafts efficiently. Future work could explore adaptive control systems for further optimization, but the current methods provide a robust foundation for similar applications.