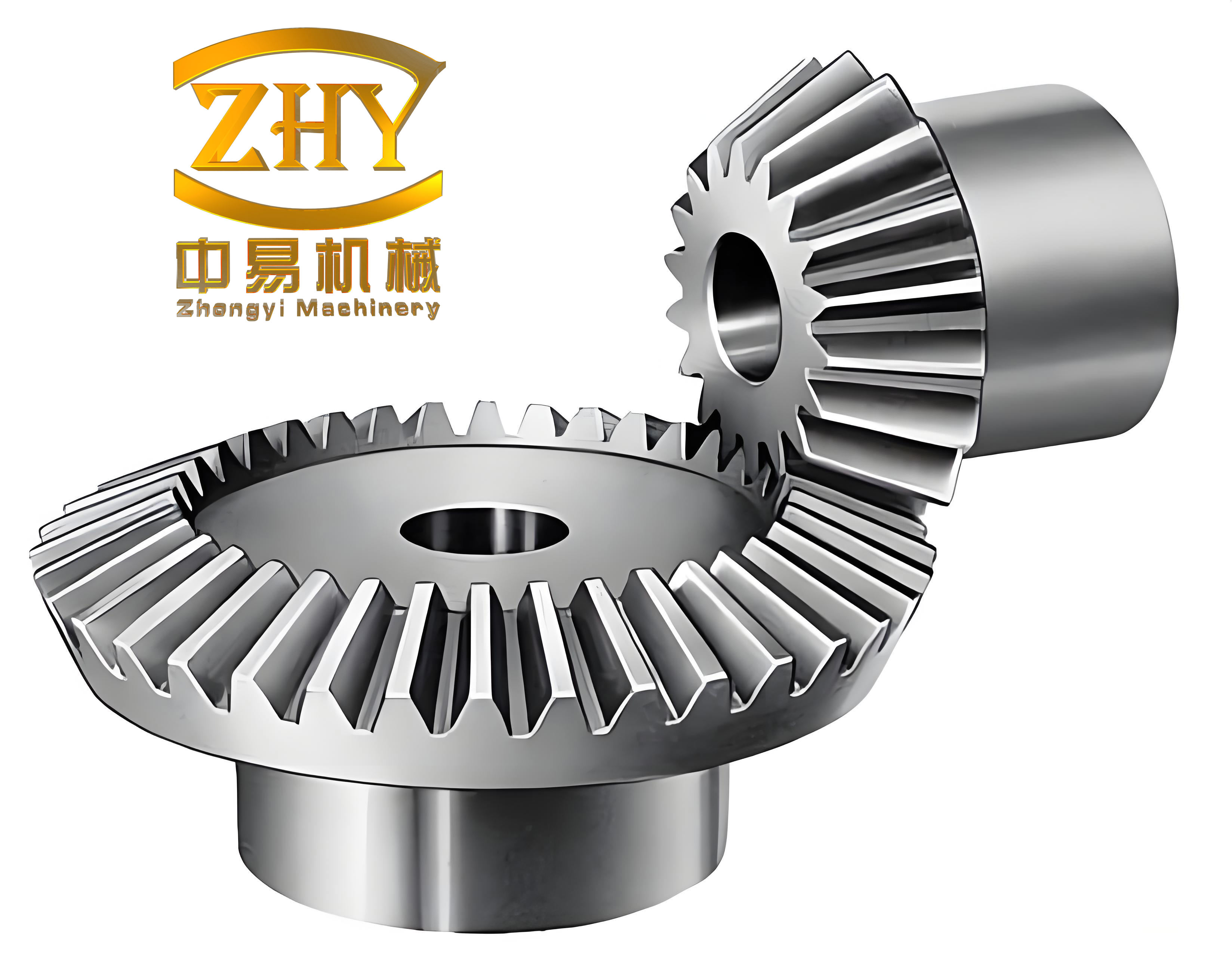

In industrial settings, the failure of critical components like straight bevel gears can halt production, especially when dealing with large prime numbers of teeth that complicate machining. I encountered such a scenario when a straight bevel gear in a龙门刨床刀架传动 system was damaged beyond repair. Given the workshop’s equipment constraints, I developed a method to machine this straight bevel gear on a vertical milling machine using differential indexing. This approach not only ensures precise division for large prime tooth counts but also leverages commonly available machinery, making it a practical solution for workshops without specialized gear-cutting equipment. The straight bevel gear in question had 73 teeth, a prime number, which prevents the use of simple indexing methods due to the inability to divide the standard 40:1 ratio of the indexing head. By adopting differential indexing, I achieved accurate tooth spacing, maintained gear geometry, and verified the results through rigorous testing. This article details the entire process, from gear analysis to final inspection, emphasizing the versatility of straight bevel gear machining.

The first step involved analyzing the damaged straight bevel gear to determine its specifications. Through meticulous measurement, I extracted key parameters essential for redrawing the gear blueprint. Accurate dimensions are critical for ensuring the new straight bevel gear matches the original functionality. Below is a table summarizing the measured parameters of the straight bevel gear:

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth (Z) | 73 | – |

| Module (m) | 3 | mm |

| Pitch Diameter (d1) | 218 | mm |

| Addendum Diameter (da1) | 220.5 | mm |

| Addendum Height (ha) | 3 | mm |

| Dedendum Height (hf) | 3.6 | mm |

| Whole Depth (h) | 6.6 | mm |

| Face Width (b) | 50 | mm |

| Pitch Angle (δ1) | 73.4° | degrees |

| Cone Distance (R1) | 113.5 | mm |

These parameters guided the machining process, with particular attention to the pitch angle and module, as they influence the cutter selection and indexing calculations. The straight bevel gear’s geometry requires precise control over tooth profile, especially at the large end, to ensure proper meshing and load distribution. Additionally, I established machining tolerances for radial runout, pitch deviation, tooth thickness, and surface roughness to meet functional requirements. The straight bevel gear’s integrity hinges on maintaining these specifications throughout the process.

Differential indexing is essential for machining straight bevel gears with prime tooth counts because simple indexing fails when the tooth count and indexing head ratio (typically 40:1) have no common factors. The principle involves connecting the indexing head’s spindle and side shaft via change gears, allowing the index plate to rotate relative to the handle. This compensates for the indivisible tooth count. The formula for the handle turn in simple indexing is $$ n = \frac{40}{Z} $$, where Z is the tooth count. For Z=73, this is not feasible, so I used a hypothetical tooth count Z0=70 for calculations. The handle turn becomes $$ n_0 = \frac{40}{Z_0} = \frac{40}{70} = \frac{28}{49} $$, meaning the handle rotates 28 holes on a 49-hole circle per division. The change gear ratio is calculated as $$ \frac{Z_1 Z_3}{Z_2 Z_4} = \frac{40 (Z_0 – Z)}{Z_0} = \frac{40 (70 – 73)}{70} = -\frac{60}{35} $$, where the negative sign indicates opposite rotation between the index plate and handle. I used a single set of change gears with Z1=60 and Z3=35, adding two idler gears to reverse direction. This setup enables precise indexing for the straight bevel gear without specialized tools.

Mounting the indexing head on a vertical milling machine was crucial to accommodate the gear’s pitch angle. I tilted the indexing head spindle to an angle equal to the pitch angle of the straight bevel gear, which is 73.4°. This orientation allows the differential gears to function unimpeded while aligning the gear blank for milling. The vertical setup also facilitates the use of a short arbor with a disk-type straight bevel gear cutter, ensuring stability during cutting. Below is a table comparing indexing methods for straight bevel gears:

| Indexing Method | Applicability | Precision | Equipment Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Indexing | Non-prime tooth counts | Moderate | Basic indexing head |

| Differential Indexing | Prime tooth counts | High | Indexing head with change gears |

| CNC Methods | All tooth counts | Very High | Advanced CNC mills |

For the straight bevel gear cutter selection, I computed the virtual tooth count using $$ Z_v = \frac{Z}{\cos \delta} = \frac{73}{\cos 73.4^\circ} \approx 103 $$. Based on the module m=3 mm and standard cutter charts, I selected a No. 7 straight bevel gear disk cutter. This cutter approximates the tooth profile for the virtual tooth count, ensuring accuracy across the gear face. Mounting the cutter on a short arbor minimized deflection, which is vital for maintaining tooth geometry in straight bevel gears.

Aligning the gear blank required a centering technique using height gauges. I scribed lines on the blank’s conical surface at a height slightly below the centerline, then rotated the blank 180° to scribe a second set. By positioning the cutter midway between these lines, I achieved symmetrical tooth spacing. This step is critical for straight bevel gears to ensure uniform load distribution and minimize noise. The initial milling pass focused on the tooth slot centers, with the cutting depth set to the whole depth h=6.6 mm, derived from $$ h = 2.2m = 2.2 \times 3 = 6.6 \, \text{mm} $$. I milled all tooth slots sequentially, using the differential indexing to advance the blank after each cut.

After milling the slot centers, I addressed the side clearances by shifting the worktable vertically. The shift distance S is given by $$ S = \frac{mb}{2R} = \frac{3 \times 50}{2 \times 113.5} \approx 0.48 \, \text{mm} $$. For the upper tooth sides, I raised the table by S and adjusted the indexing head to lightly contact the small end of the slot, then milled the large end excess. For the lower sides, I lowered the table by 2S=0.96 mm and reversed the indexing direction. This two-step process ensures the straight bevel gear’s tooth thickness meets specifications at both ends. The formula for tooth thickness variation accounts for the taper; for instance, the chordal tooth thickness at the large end is critical and can be verified using $$ S_{\text{large}} = m Z_v \sin\left(\frac{90^\circ}{Z_v}\right) $$ and the chordal addendum as $$ h_{\text{large}} = m \left[1 + \frac{Z_v}{2} \left(1 – \cos\left(\frac{90^\circ}{Z_v}\right)\right)\right] $$. Similarly, for the small end, I used the small-end module in calculations to check tolerances.

Quality control involved measuring tooth thickness and tooth direction error. I used a gear tooth caliper to verify the chordal tooth thickness at the large end, ensuring it matched the drawing specifications. For tooth direction error, I inserted pairs of pins into opposing tooth slots; if the pins touched at the tips, the tooth alignment was correct. This method detects deviations in the tooth trace, which is vital for straight bevel gears to prevent premature wear. Surface roughness was assessed with a profilometer, confirming it met the required standards. The table below outlines key inspection parameters for straight bevel gears:

| Inspection Parameter | Method | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|

| Chordal Tooth Thickness | Gear Tooth Caliper | ±0.05 mm |

| Tooth Direction Error | Pin Insertion Test | Max 0.1 mm deviation |

| Radial Runout | Dial Indicator | 0.05 mm |

| Surface Roughness | Profilometer | Ra 1.6 µm |

Throughout the process, I encountered challenges such as vibration during milling, which I mitigated by using sharp cutters and stable workholding. The differential indexing required precise setup of change gears to avoid backlash, but once configured, it provided consistent results. This method demonstrates that straight bevel gears with large prime tooth counts can be machined accurately on standard vertical mills, expanding workshop capabilities without costly investments. The success of this approach underscores the importance of adaptive machining strategies for straight bevel gears in repair and prototyping scenarios.

In conclusion, machining a straight bevel gear with 73 teeth using differential indexing on a vertical milling machine proved effective and economical. The straight bevel gear met all dimensional and surface quality requirements, validating the method’s precision. This technique not only resolves immediate repair needs but also offers a scalable solution for other large prime straight bevel gears. Future work could explore automation of the indexing process or integration with digital tooling for enhanced efficiency. Ultimately, the straight bevel gear’s performance in the transmission system confirmed the machining approach’s reliability, highlighting the value of innovative methods in traditional machining environments.