In modern mechanical design, the efficient creation of accurate gear models is crucial for virtual prototyping and simulation. As an engineer specializing in gear design, I have explored methods to streamline the parametric modeling of straight bevel gears in Pro/ENGINEER (Pro/E). This approach not only enhances design efficiency but also ensures the correctness of gear meshing, which is vital for applications like differential systems in automotive engineering. In this article, I will share my methodology for rapid parametric modeling and assembly of straight bevel gears, focusing on key parameters, equations, and steps that leverage Pro/E’s capabilities. Throughout, I will emphasize the importance of the straight bevel gear as a fundamental component in power transmission systems.

The design process begins with defining the essential parameters of the straight bevel gear. These parameters include the number of teeth, module, pressure angle, and cone dimensions, which collectively determine the gear’s geometry and performance. Below, I present a table summarizing the primary parameters used in this study, based on a planetary gear example from a differential system. This table serves as a reference for subsequent modeling steps.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth | z | 10 | – |

| Module | m | 3.5 | mm |

| Face Width | b | 8.83 | mm |

| Pressure Angle | α | 22.5 | ° |

| Pitch Diameter | d | 35 | mm |

| Pitch Cone Angle | δ | 33.69 | ° |

| Cone Distance | R | 31.55 | mm |

| Addendum | ha | 3.57 | mm |

| Dedendum | hf | 2.688 | mm |

To initiate the modeling in Pro/E, I start by setting up the parameters and their relationships. Using the “Tools” → “Parameters” menu, I input the variables and define relations that automate calculations. For instance, the pitch diameter is derived from the module and number of teeth: $$d = m \times z$$ Similarly, the cone distance R and other dimensions are computed using trigonometric functions based on the pitch cone angle δ. This parametric approach allows for quick updates if any parameter changes, which is essential for iterative design processes involving straight bevel gears.

The next step involves creating the pitch cone generatrix, which serves as the foundation for the straight bevel gear geometry. I select the FRONT plane as the sketch plane and draw a line representing the pitch cone generatrix. The angle of this line is set to the pitch cone angle δ, and its length is related to the pitch radius. Specifically, the relationship is defined as: $$ \text{sd1} = δ = 33.69° $$ and $$ \text{sd2} = r = \frac{d}{2} = 17.5 \, \text{mm} $$ Here, “sd1” and “sd2” are dimension symbols in Pro/E that control the sketch. This generatrix is critical because it defines the overall cone shape of the straight bevel gear and influences subsequent curves and surfaces.

After establishing the pitch cone generatrix, I proceed to create the involute tooth profile. This requires constructing auxiliary planes and coordinate systems. First, I create a datum plane DTM1 by rotating the FRONT plane by 90 degrees around an axis perpendicular to the pitch cone generatrix. This plane is used to sketch the base circles and involute curves. On DTM1, I place points PNT0 and PNT1 along the generatrix, which help in positioning a reference coordinate system CS0. The orientation of CS0 is set with the X-axis along the direction from PNT0 to PNT1 and the Z-axis normal to DTM1.

Within this coordinate system, I sketch four base circles: the addendum circle, pitch circle, base circle, and dedendum circle. Their diameters are calculated using the following relations: $$ d_d = \frac{d}{\cos(\delta)} $$ $$ d_{da} = d_d + 2h_a $$ $$ d_{df} = d_d – 2h_f $$ $$ d_{db} = d_d \times \cos(\alpha) $$ where \( d_d \) is the derived pitch diameter on the base plane, \( d_{da} \) is the addendum circle diameter, \( d_{df} \) is the dedendum circle diameter, and \( d_{db} \) is the base circle diameter. These circles form the basis for generating the involute curve.

The involute curve is created using a parametric equation in Pro/E’s curve tool. I select the “From Equation” option, choose the CS0 coordinate system, and set the type to Cartesian. The involute equations are as follows: $$ r = \frac{d_{db}}{2} $$ $$ \theta = t \times 45 $$ $$ x = r \times \cos(\theta) + \pi \times r \times \frac{\theta}{180} \times \sin(\theta) $$ $$ y = r \times \sin(\theta) – \pi \times r \times \frac{\theta}{180} \times \cos(\theta) $$ $$ z = 0 $$ Here, \( t \) is a parameter that varies from 0 to 1, and the equations describe the involute profile in the XY-plane. This curve represents the tooth flank of the straight bevel gear and is essential for accurate meshing.

To complete the tooth profile, I mirror the involute curve about a plane of symmetry. I create a datum axis A1 through points PNT0 and PNT1, and then identify point PNT2 at the intersection of the pitch circle and the pitch cone generatrix. A new datum plane DTM2 is defined through PNT2 and axis A1. Rotating DTM2 by \( \frac{90}{z} \) degrees gives DTM3, which serves as the mirror plane. The mirrored involute curve ensures symmetry for the straight bevel gear teeth, which is crucial for uniform load distribution.

With the tooth profile defined, I move on to creating the gear blank实体. Using the “Revolve” tool in Pro/E, I sketch the profile of the straight bevel gear on the FRONT plane. This sketch includes the cone surfaces defined by the pitch, addendum, and dedendum generatrices. Relations are applied to control dimensions, such as the cone angles and heights. For example, the addendum and dedendum are adjusted based on whether equal or unequal clearance is desired, but in this case, I focus on a standard straight bevel gear design. The revolve operation generates a solid cone representing the gear blank.

The next critical step is generating the tooth spaces. I use the “Sweep Blend” command to create a single tooth slot. The sweep trajectory is the portion of the pitch cone generatrix between PNT1 and PNT2. For the sections, I set the first section as the involute curve (ensuring it is closed for material removal) and the second section as a point at the tip to form a tapered slot. After removing material, this results in one tooth space. Then, I group this feature and use the “Pattern” tool to create all teeth around the axis. The number of instances equals the number of teeth z, and the angular spacing is \( \frac{360}{z} \) degrees. This approach efficiently generates the complete set of teeth for the straight bevel gear.

To finalize the straight bevel gear model, I add features like a central bore, keyway, and chamfers using standard Pro/E tools. These elements are parameterized to adapt to changes in the main gear dimensions. For instance, the bore diameter might be related to the pitch diameter through a relation like $$ \text{bore\_diameter} = 0.3 \times d $$ This ensures that the model remains consistent and easy to modify.

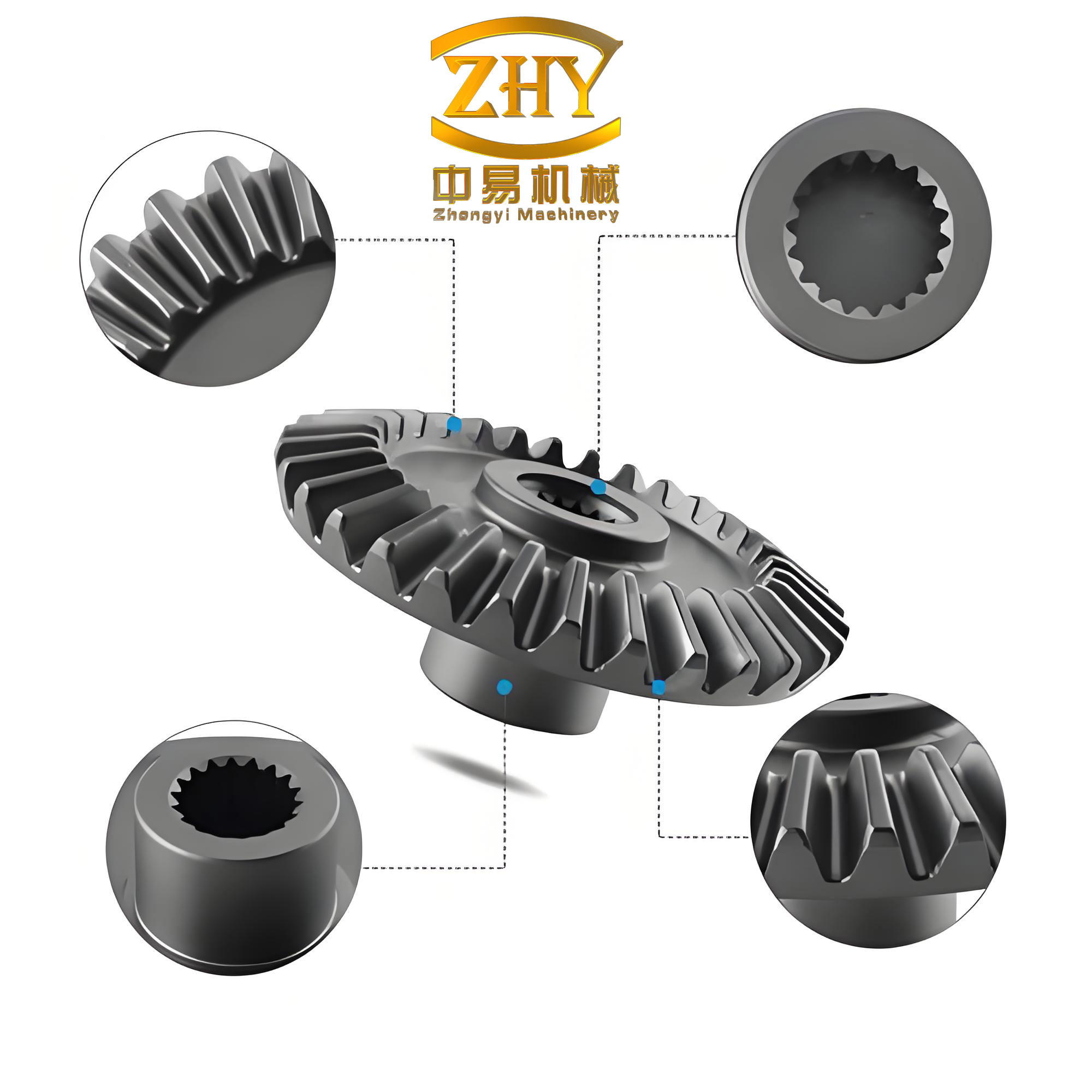

Now, I will insert an image that illustrates a typical straight bevel gear, which can help visualize the geometry discussed. This image is placed here to complement the textual description.

Assembly of straight bevel gears, such as in a planetary gear system, is the next phase. I create auxiliary planes through the cone vertices of both gears, aligned with their respective pitch cone generatrices. In the assembly module, I use constraints like “Align” and “Mate” to position the gears correctly. For example, the pitch cones of the mating straight bevel gears must be tangent to ensure proper meshing. The alignment of the axes and the symmetry planes guarantees that the gears rotate without interference. This assembly process is vital for virtual prototyping and subsequent motion analysis.

To facilitate simulation, I export the assembled model to formats like .x_t (Parasolid), which is compatible with various CAE software. This allows for dynamic analysis of the straight bevel gear system under operational conditions. The parametric nature of the model means that any design changes can be quickly propagated through the assembly, saving time in the development cycle.

In summary, the rapid parametric modeling of straight bevel gears in Pro/E relies on a systematic approach that integrates mathematical relations and geometric constructions. The key insight is the use of a single pitch cone generatrix to derive all necessary curves and surfaces. Below, I include a table that outlines the main steps and their corresponding equations or tools, which can serve as a quick reference for engineers.

| Step | Description | Key Equations/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parameter Setup | $$ d = m \times z $$, $$ R = \frac{d}{2 \sin(\delta)} $$ |

| 2 | Pitch Cone Generatrix | Sketch on FRONT plane with relations |

| 3 | Involute Curve Creation | $$ x = r \cos(\theta) + \pi r \frac{\theta}{180} \sin(\theta) $$, $$ y = r \sin(\theta) – \pi r \frac{\theta}{180} \cos(\theta) $$ |

| 4 | Tooth Profile Mirroring | Datum planes and axis-based mirroring |

| 5 | Gear Blank Creation | Revolve tool with parametric sketch |

| 6 | Tooth Slot Generation | Sweep Blend with trajectory and sections |

| 7 | Pattern Teeth | Circular pattern with $$ \frac{360}{z} $$ increment |

| 8 | Final Features | Hole, keyway, and chamfer tools |

| 9 | Assembly | Align and mate constraints |

| 10 | Export for Simulation | Save as .x_t or other neutral formats |

The advantages of this method are numerous. It reduces the number of auxiliary elements needed—traditionally, multiple planes and points were required, but now, with a focus on the pitch cone generatrix and its relations, the process is streamlined. This is particularly beneficial for straight bevel gears, where accuracy in the tooth geometry directly impacts performance. Moreover, the parametric setup allows for easy scaling to different sizes or specifications, making it ideal for custom gear design.

In conclusion, as an engineer, I have found that this approach to modeling straight bevel gears in Pro/E significantly enhances design efficiency. By leveraging parametric relations and Pro/E’s advanced features, I can quickly generate accurate models that are ready for assembly and simulation. The straight bevel gear, with its conical shape and involute teeth, is a complex component, but with this methodology, it becomes manageable and adaptable to various engineering applications. Future work could involve extending this to spiral bevel gears or integrating with finite element analysis for stress evaluation, but the core principles remain rooted in parametric design.