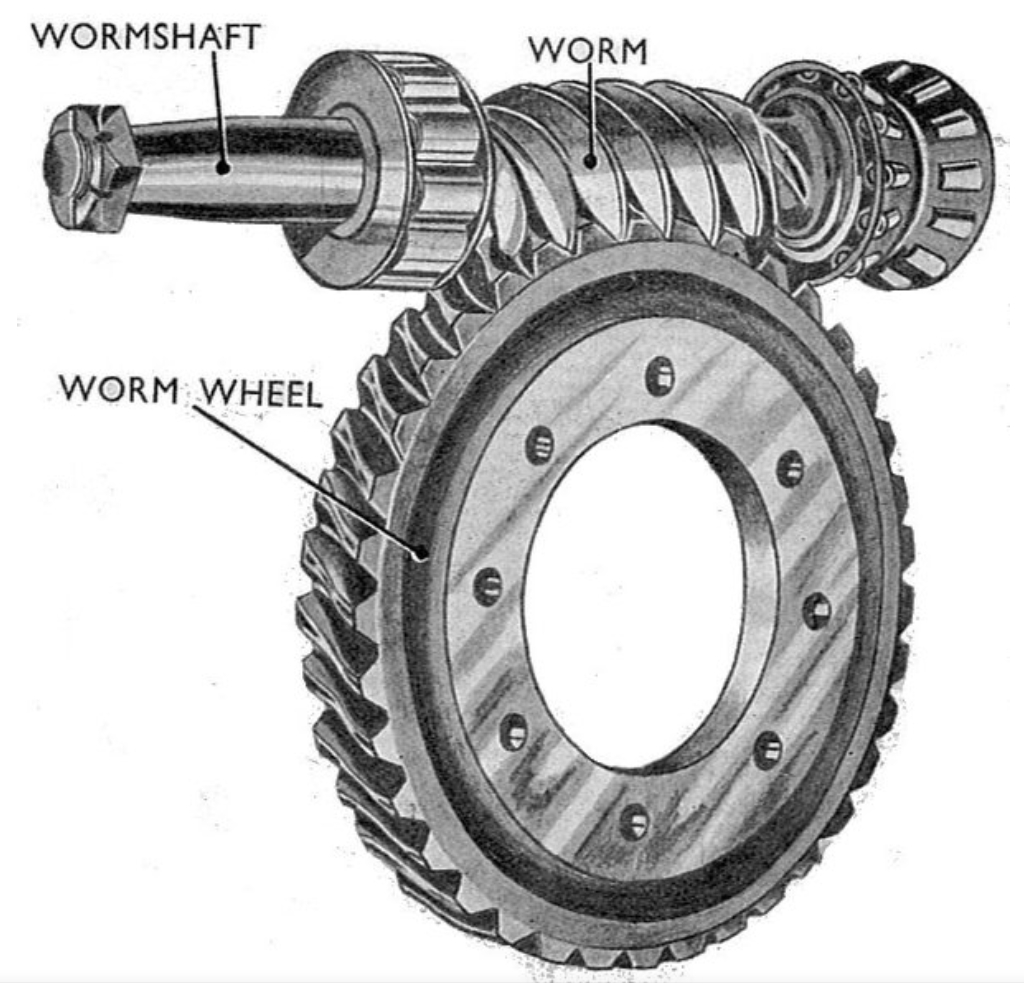

The pursuit of high-performance power transmission systems necessitates continuous innovation in gear design. Among various configurations, the worm gear drive offers distinct advantages for achieving high reduction ratios in compact spaces. However, conventional designs often suffer from significant sliding friction, leading to reduced efficiency, heat generation, and potential failure modes like wear and scuffing. A novel approach to mitigate these issues is the development of an inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass worm drive. This design replaces the traditional solid worm wheel teeth with rows of rotating rollers, effectively transforming detrimental sliding friction into more favorable rolling friction. The unique geometry, featuring rollers inclined relative to the radial direction of the wheel and an hourglass-shaped worm generated by enveloping a cylindrical surface, provides multi-tooth engagement and inherent lubrication channels. Understanding the lubrication performance under realistic conditions, where perfectly smooth surfaces are non-existent, is paramount for optimizing the reliability and lifespan of this advanced worm gear drive.

Elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL) theory is the cornerstone for analyzing the fluid film formation between heavily loaded, non-conforming contacts like those in gear meshes. In an ideal scenario with perfectly smooth surfaces, the lubricant film thickness is governed by the balance of hydrodynamic pressure generation and elastic deformation of the contacting bodies. However, in practical worm gear drive applications, manufactured surfaces possess a certain degree of roughness. When the calculated EHL film thickness is of the same order of magnitude as the surface roughness amplitude, the asperities (roughness peaks and valleys) can dramatically alter the pressure distribution and film profile, potentially leading to mixed lubrication or even boundary lubrication regimes. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis of the inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass worm drive must integrate surface topography effects into the EHL model to accurately predict its tribological performance.

The core of the lubrication analysis lies in simplifying the complex spatial line contact between the worm thread and the roller into a manageable model. For the purpose of EHL calculation, the contact at any given meshing instant can be represented by an equivalent contact between a cylinder and a plane. The key parameters for this simplified line contact model are derived from the kinematic and load analysis of the worm gear drive. The equivalent radius of curvature ($R$), the entrainment velocity ($v_{jx}$), and the load per unit length ($w$) vary along the path of contact from the entry to the exit of the mesh. These variations are crucial as they directly influence the film-building capability.

The mathematical foundation for the isothermal EHL analysis of this worm gear drive is built upon the following set of equations, expressed here in dimensionless form for numerical stability. The governing equation is the Reynolds equation, which describes pressure generation within the lubricant film:

$$

\frac{d}{dX}\left(\varepsilon \frac{dP}{dX}\right) = \frac{d(\rho^* H)}{dX} + \frac{d(\rho^* H)}{dT}

$$

where $\varepsilon = \frac{\rho^* H^3}{\eta^* \lambda}$, $\lambda = \frac{12 \eta_0 U R^2}{p_h b^2}$, $P$ is the dimensionless pressure, $H$ is the dimensionless film thickness, $\rho^*$ is the dimensionless density, $\eta^*$ is the dimensionless viscosity, and $X$ is the dimensionless coordinate along the contact. The boundary conditions are $P(X_{in})=0$ at the inlet and $P(X_{out}) = dP(X_{out})/dX = 0$ at the outlet.

The film thickness equation is central to incorporating surface roughness and elastic deformation. For a surface with a single, idealized asperity (peak or valley) located at the center of the contact, the roughness function can be modeled as $S(X) = \delta (|X| – 1)^2$, where $\delta$ is the dimensionless amplitude of the roughness. The complete film thickness equation is:

$$

H(X) = H_0 + \frac{X^2}{2} – \frac{1}{\pi} \int_{X_{in}}^{X_{out}} \ln|X – X’| P(X’) dX’ \pm S(X)

$$

where $H_0$ is the dimensionless central film thickness for rigid bodies, and the $\pm$ sign accounts for a roughness peak ($-$) or valley ($+$). The integral term represents the elastic deformation of the surfaces due to the pressure distribution.

The pressure-dependence of the lubricant’s properties is critical. The viscosity variation is commonly described by the Barus-like equation:

$$

\eta^* = \exp\left\{ (\ln \eta_0 + 9.67) \left[ (1 + 5.1 \times 10^{-9} p)^z – 1 \right] \right\}

$$

where $z = \alpha / [5.1 \times 10^{-9} (\ln \eta_0 + 9.667)]$ and $\alpha$ is the pressure-viscosity coefficient. The density variation is given by:

$$

\rho^* = 1 + \frac{0.6 \times 10^{-9} p}{1 + 1.7 \times 10^{-9} p}

$$

Finally, the solution must satisfy the force equilibrium condition, ensuring the integrated pressure balances the applied load:

$$

W = \int_{X_{in}}^{X_{out}} P(X) dX = \frac{\pi}{2}

$$

Solving this coupled system of integral-differential equations requires robust numerical methods. A common approach is to discretize the equations using finite differences and then solve the resulting nonlinear system using the Newton-Raphson method. The solution yields the pressure profile $P(X)$ and the film thickness profile $H(X)$ across the contact domain.

The analysis of the inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass worm drive reveals significant insights when surface roughness is considered. The presence of a single asperity, whether a peak or a valley, locally perturbs the otherwise smooth pressure and film profiles obtained for ideal surfaces.

| Roughness Type | Effect on Pressure Profile | Effect on Film Thickness Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Single Roughness Valley | Causes a local pressure dip within the valley. The pressure is redistributed to the smoother regions on either side, leading to two distinct secondary pressure peaks. The magnitude of the dip and the secondary peaks increases with valley depth ($\delta$). | Causes a local increase in film thickness within the valley. The film thickness in the inlet region is significantly increased with larger $\delta$. The characteristic film necking (minimum film thickness) near the outlet is delayed. |

| Single Roughness Peak | Causes a sharp local pressure spike over the peak. A secondary pressure peak also forms. Both spike and secondary peak heights increase with peak amplitude ($\delta$). | Causes a local decrease in film thickness over the peak. The film thickness in the inlet region is reduced with larger $\delta$. The film necking occurs earlier in the contact. |

More importantly, the lubrication condition varies throughout the meshing cycle of a single tooth pair in the worm gear drive. Analyzing different engagement points—from the first tooth beginning to mesh to the fourth—shows that the most critical moment for lubrication occurs when the third tooth starts to engage. At this point, the load per unit length is near its maximum, and the entrainment velocity is relatively low, resulting in the smallest calculated minimum film thickness and the highest secondary pressure peaks. The introduction of surface roughness exacerbates this condition, especially with roughness peaks, making this region the most prone to lubricant film collapse and potential surface damage.

The design parameters of the worm gear drive have a direct impact on its EHL performance. The table below summarizes the influence of key geometrical parameters on the lubrication characteristics at the critical meshing point, considering a fixed roughness amplitude.

| Design Parameter | Effect on EHL Pressure | Effect on EHL Film Thickness | Design Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roller Radius ($R_z$) Increasing |

Decreases the pressure over the asperity. Increases and shifts the secondary pressure peak towards the outlet. | Decreases the overall film thickness. Delays the necking position. | Excessively large roller radii are detrimental to forming a thick protective film. |

| Roller Offset Distance ($c_2$) Increasing |

For a valley: decreases asperity pressure, increases secondary peak. For a peak: slightly increases asperity pressure, decreases secondary peak. | Decreases the overall film thickness. Delays the necking position. | Larger offset distances reduce film thickness and should be optimized. |

| Throat Diameter Coefficient ($k$) Increasing |

For a valley: decreases both asperity and secondary pressure. For a peak: secondary pressure increases and moves inlet-wards. | Decreases the overall film thickness. Delays the necking position. | Very small throat coefficients are unfavorable for lubrication; a moderate value is preferable. |

The underlying mechanism for the pressure perturbations can be explained by flow constriction. A roughness peak acts as a constriction in the lubricant flow path. To maintain flow continuity, the lubricant pressure must rise sharply upstream of the constriction (the peak), creating the observed pressure spike. Conversely, a roughness valley acts as a local expansion, reducing the flow resistance and thus causing a pressure dip, with the load supported by increased pressure in the adjacent smoother zones. The interaction between this perturbed pressure field and the surface elasticity is what generates the corresponding film thickness variations.

In conclusion, the elastohydrodynamic lubrication analysis of the inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass worm drive underscores the critical importance of accounting for surface roughness. The study demonstrates that roughness asperities significantly distort the pressure and film thickness distributions compared to smooth-surface predictions. While both peaks and valleys are influential, peaks are particularly detrimental as they create local high-pressure zones that thin the lubricant film, increasing the risk of asperity contact. The meshing phase where the third tooth begins engagement is identified as the most vulnerable point for lubrication failure in this worm gear drive. To ensure robust EHL performance and enhance the durability of the transmission, the design must carefully balance parameters: the roller radius and offset distance should not be excessively large, and the throat diameter coefficient should not be too small. Ultimately, employing high-precision manufacturing processes to minimize surface roughness amplitude is a highly effective strategy for maximizing the load-carrying capacity and operational life of this innovative worm gear drive system. Future work could extend this model to include thermal effects and more realistic, multi-scale roughness profiles to further refine the lubrication understanding.