In the field of mechanical transmission systems, the worm gear drive stands as a critical foundational component due to its ability to provide high reduction ratios and compact design. However, traditional worm drives often suffer from issues such as sliding friction, which leads to increased wear, heat generation, and reduced efficiency. To address these challenges, we propose a novel configuration known as the roller enveloping end face engagement worm gear drive. This innovative worm gear drive combines the advantages of rolling contact from roller enveloping designs with the multi-tooth engagement characteristics of end face meshing, thereby enhancing performance and durability. In this article, we delve into the meshing theory, mathematical modeling, and performance analysis of this worm gear drive, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of its operation and benefits.

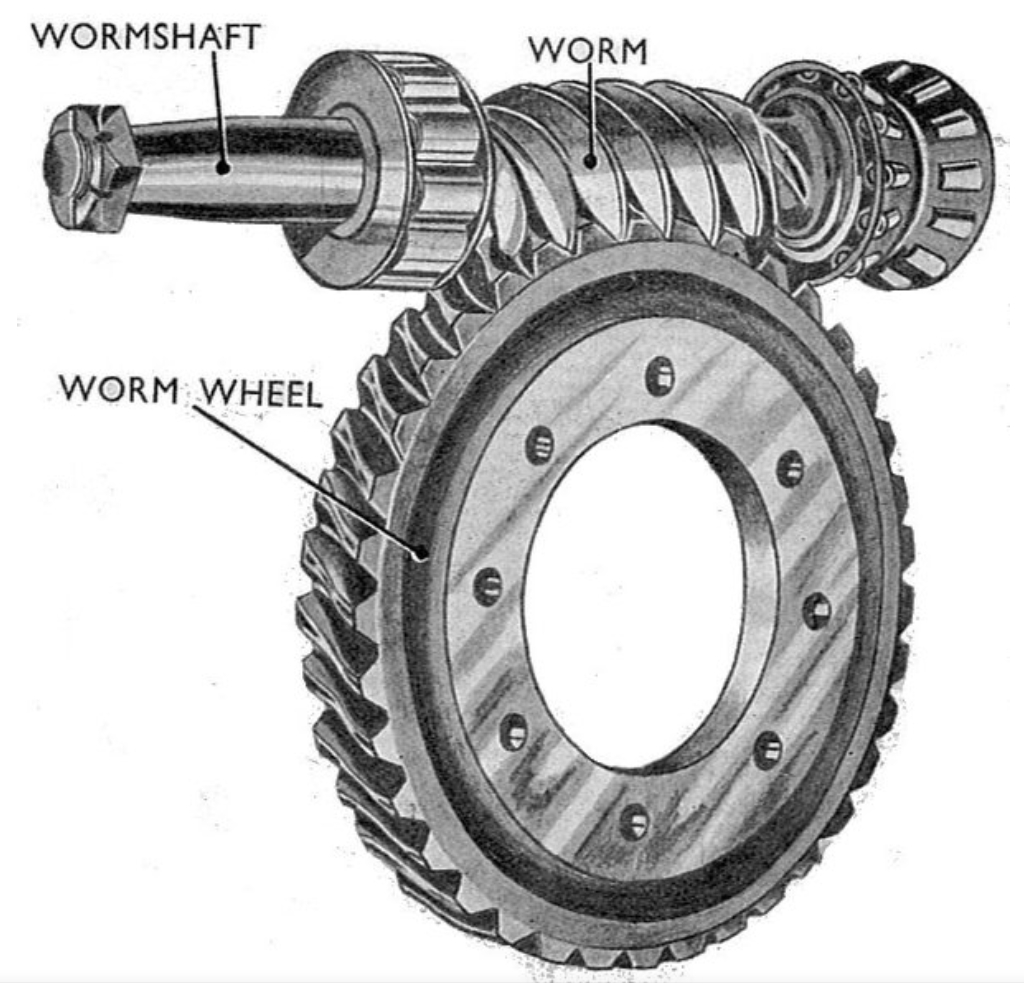

The roller enveloping end face engagement worm gear drive operates on a principle that transforms sliding friction into rolling friction, thereby mitigating common drawbacks associated with conventional worm gear drives. The worm gear drive consists of a worm shaft with two segments—left and right—each engaging with the worm wheel symmetrically. The worm wheel teeth are designed as rollers that can rotate about their own axes, facilitated by needle bearings to minimize friction. This configuration not only reduces wear but also allows for multiple tooth pairs to be in simultaneous contact, increasing load capacity and eliminating backlash. The end face engagement aspect refers to the meshing occurring along the lateral sides of the worm wheel, as opposed to the traditional radial engagement, which further enhances the contact area and stability. We will explore the working and forming principles in detail, establishing a foundation for the mathematical derivations that follow.

To analyze the meshing behavior of this worm gear drive, we first establish a mathematical model based on differential geometry and coordinate transformations. The coordinate systems include static and dynamic frames for both the worm and worm wheel, as well as a local frame attached to the roller surface. Let us define the following coordinate systems: $\sigma_1 (i_1, j_1, k_1)$ as the static frame for the worm, $\sigma_2 (i_2, j_2, k_2)$ as the static frame for the worm wheel, $\sigma_1′ (i_1′, j_1′, k_1′)$ as the dynamic frame for the worm, and $\sigma_2′ (i_2′, j_2′, k_2′)$ as the dynamic frame for the worm wheel. The worm rotates about axis $k_1 = k_1’$ with angular velocity $\omega_1$, while the worm wheel rotates about axis $k_2 = k_2’$ with angular velocity $\omega_2$. The center distance is denoted as $A$, and the rotation angles are $\phi_1$ for the worm and $\phi_2$ for the worm wheel, related by the transmission ratio $i_{12} = \phi_1 / \phi_2 = \omega_1 / \omega_2 = Z_2 / Z_1$, where $Z_1$ is the number of worm threads and $Z_2$ is the number of worm wheel teeth. Additionally, we set up a local frame $\sigma_0 (i_0, j_0, k_0)$ at the center of the roller top circle, with parameters $u$ and $\theta$ describing the roller surface. The roller surface vector in $\sigma_0$ is given by:

$$ \mathbf{r}_0 = x_0 \mathbf{i}_0 + y_0 \mathbf{j}_0 + z_0 \mathbf{k}_0 $$

$$ x_0 = R \cos\theta, \quad y_0 = R \sin\theta, \quad z_0 = u $$

where $R$ is the radius of the roller. Coordinate transformations between these frames are essential for deriving meshing equations. The transformation matrices are derived using rotation and translation operations. For instance, the transformation from $\sigma_1’$ to $\sigma_1$ involves a rotation by $\phi_1$:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{i}_1 \\ \mathbf{j}_1 \\ \mathbf{k}_1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\phi_1 & -\sin\phi_1 & 0 & 0 \\ \sin\phi_1 & \cos\phi_1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{i}_1′ \\ \mathbf{j}_1′ \\ \mathbf{k}_1′ \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = M_{11′} \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{i}_1′ \\ \mathbf{j}_1′ \\ \mathbf{k}_1′ \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

Similarly, transformations between $\sigma_2’$ and $\sigma_2$, and between $\sigma_1’$ and $\sigma_2’$, are established. The relative velocity and angular velocity vectors are then derived in the local frame $\sigma_p (e_1, e_2, \mathbf{n})$, where $\mathbf{n}$ is the unit normal to the contact surface. These vectors are crucial for formulating the meshing conditions. The relative velocity $\mathbf{V}^{(1’2′)}$ and relative angular velocity $\mathbf{\omega}^{(1’2′)}$ in $\sigma_p$ are expressed as:

$$ \mathbf{V}^{(1’2′)} = V_1^{(1’2′)} \mathbf{e}_1 + V_2^{(1’2′)} \mathbf{e}_2 + V_n^{(1’2′)} \mathbf{n} $$

$$ V_1^{(1’2′)} = -B_2 \sin\theta + B_3 \cos\theta, \quad V_2^{(1’2′)} = -B_1, \quad V_n^{(1’2′)} = B_2 \cos\theta + B_3 \sin\theta $$

$$ \mathbf{\omega}^{(1’2′)} = \omega_1^{(1’2′)} \mathbf{e}_1 + \omega_2^{(1’2′)} \mathbf{e}_2 + \omega_n^{(1’2′)} \mathbf{n} $$

$$ \omega_1^{(1’2′)} = \cos\phi_2 \sin\theta – i_{21} \cos\theta, \quad \omega_2^{(1’2′)} = \sin\phi_2, \quad \omega_n^{(1’2′)} = -\cos\theta \cos\phi_2 – i_{21} \sin\theta $$

where $B_1, B_2, B_3$ are constants derived from geometric parameters. Using these, we can proceed to derive the meshing function and equation for this worm gear drive.

The meshing function $\Phi$ is defined as the dot product of the unit normal vector and the relative velocity vector at the contact point, which must be zero for continuous meshing. Thus, we have:

$$ \Phi = \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{V}^{(1’2′)} = V_n^{(1’2′)} = M_1 \cos\phi_2 + M_2 \sin\phi_2 + M_3 = 0 $$

where the coefficients $M_1, M_2, M_3$ are functions of the parameters $\theta$, $u$, and geometric constants. Specifically, for this worm gear drive, they are given by:

$$ M_1 = \sin\theta (a_2 – u), \quad M_2 = 0, \quad M_3 = -i_{21} \cos\theta (a_2 – u) – A \sin\theta $$

Here, $a_2$ is a coordinate from the roller center position. The meshing equation $\Phi = 0$ defines the relationship between parameters at the contact points. To visualize the contact pattern, we derive the contact lines on the roller surface by fixing $\phi_2$ and solving the meshing equation along with the roller surface equation. The contact line equations are:

$$ \mathbf{r}_0 = x_0 \mathbf{i}_0 + y_0 \mathbf{j}_0 + z_0 \mathbf{k}_0, \quad u = f(\theta, \phi_2) = \frac{P_1}{P_2}, \quad \phi_2 = \text{constant} $$

where $P_1$ and $P_2$ are expressions derived from the meshing conditions. For $\theta \in [0, \pi]$, the contact lines correspond to the upper tooth engagement, while for $\theta \in [-\pi, 0]$, they correspond to the lower tooth engagement. In this worm gear drive, the contact lines are nearly straight, and multiple tooth pairs are engaged simultaneously, enhancing load distribution. Next, the worm tooth surface equation is derived as the envelope of the roller surface family parameterized by $\phi_2$. The worm tooth surface vector in $\sigma_1’$ is:

$$ \mathbf{r}_1′ = x_1 \mathbf{i}_1′ + y_1 \mathbf{j}_1′ + z_1 \mathbf{k}_1′ $$

$$ x_1 = -\cos\phi_1 \cos\phi_2 (a_2 – z_0) + \cos\phi_1 \sin\phi_2 x_0 – y_0 \sin\phi_1 + A \cos\phi_1 $$

$$ y_1 = \sin\phi_1 \cos\phi_2 (a_2 – z_0) – \sin\phi_1 \sin\phi_2 x_0 – y_0 \cos\phi_1 – A \sin\phi_1 $$

$$ z_1 = -\sin\phi_2 (a_2 – z_0) – \cos\phi_2 x_0 $$

$$ \mathbf{r}_0 = x_0 \mathbf{i}_0 + y_0 \mathbf{j}_0 + z_0 \mathbf{k}_0, \quad u = \frac{P_1}{P_2}, \quad \phi_2 = i_{21} \phi_1 \quad (-\pi \le \phi_1 \le \pi) $$

This equation describes the complex geometry of the worm tooth surface generated by the enveloping process. To further analyze the performance of this worm gear drive, we derive key meshing characteristics such as the induced normal curvature, lubrication angle, relative entrainment velocity, and self-rotation angle. These parameters are critical for assessing friction, wear, and lubrication efficiency.

The induced normal curvature $k_\delta^{(1’2′)}$ measures the conformity between the contacting surfaces and influences contact stress. For this worm gear drive, it is given by:

$$ k_\delta^{(1’2′)} = -k_\delta^{(2’1′)} = -\frac{(\omega_2^{(1’2′)} + V_1^{(1’2′)} / R)^2 + (\omega_1^{(1’2′)})^2}{\psi} $$

where $\psi$ is a denominator term derived from the geometry. Analysis shows that the induced normal curvature remains within a favorable range, typically between 0.079 mm⁻¹ and 0.17 mm⁻¹ for standard parameters, indicating good surface conformity and reduced contact pressure compared to traditional worm gear drives. The lubrication angle $\mu$ is defined as the angle between the relative velocity direction and the tangent to the contact line. A value close to 90° promotes effective fluid film formation. For this worm gear drive, $\mu$ is calculated as:

$$ \mu = \arcsin\left( \frac{-V_1^{(1’2′)} (V_1^{(1’2′)} / R – \omega_2^{(1’2′)}) + V_2^{(1’2′)} \omega_1^{(1’2′)}}{\sqrt{(V_1^{(1’2′)})^2 + (V_2^{(1’2′)})^2} \sqrt{(V_1^{(1’2′)} / R – \omega_2^{(1’2′)})^2 + (\omega_1^{(1’2′)})^2}} \right) $$

In practice, $\mu$ is maintained between 89° and 90°, ensuring excellent lubrication conditions. The relative entrainment velocity $V_{jx}$ represents the average velocity component along the contact normal, which aids in hydrodynamic lubrication. It is expressed as:

$$ V_{jx} = 0.5 (V_{1’\sigma} + V_{2’\sigma}) $$

$$ V_{1’\sigma} = \frac{V_{1’1} (V_1^{(1’2′)} / R – \omega_2^{(1’2′)}) + V_{1’2} \omega_1^{(1’2′)}}{\sqrt{(V_1^{(1’2′)} / R – \omega_2^{(1’2′)})^2 + (\omega_1^{(1’2′)})^2}} $$

$$ V_{2’\sigma} = \frac{V_{2’1} (V_1^{(1’2′)} / R – \omega_2^{(1’2′)}) + V_{2’2} \omega_1^{(1’2′)}}{\sqrt{(V_1^{(1’2′)} / R – \omega_2^{(1’2′)})^2 + (\omega_1^{(1’2′)})^2}} $$

For typical operating conditions, $V_{jx}$ ranges from 10 mm/s to 23 mm/s, facilitating the formation of a dynamic pressure oil film. Lastly, the self-rotation angle $\mu_{z0}$ indicates the tendency of the rollers to rotate about their axes, which enhances rolling contact. It is defined as the angle between the relative velocity vector and the roller axis $k_0$:

$$ \mu_{z0} = \arccos\left( \frac{\mathbf{k}_0 \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)}}{|\mathbf{v}^{(12)}|} \right) = \arccos\left( \frac{v_2^{(12)}}{\sqrt{(v_1^{(12)})^2 + (v_2^{(12)})^2}} \right) $$

Values of $\mu_{z0}$ are typically between 84.5° and 90°, indicating favorable self-rotation and reduced sliding friction. To summarize these characteristics, we present a table comparing key parameters of the roller enveloping end face engagement worm gear drive with a conventional worm gear drive.

| Parameter | Roller Enveloping End Face Engagement Worm Gear Drive | Conventional Worm Gear Drive |

|---|---|---|

| Induced Normal Curvature (mm⁻¹) | 0.079 – 0.17 | ~0.2 |

| Lubrication Angle (°) | 89 – 90 | 80 – 88 |

| Relative Entrainment Velocity (mm/s) | 10 – 23 | Lower range |

| Self-Rotation Angle (°) | 84.5 – 90 | ~76 |

| Simultaneous Tooth Pairs | Multiple (e.g., 5 pairs) | Fewer |

The mathematical derivations and analysis demonstrate that the roller enveloping end face engagement worm gear drive offers significant advantages over traditional designs. By incorporating rolling contact through rollers and leveraging end face engagement for multi-tooth meshing, this worm gear drive reduces friction, wear, and heat generation, while increasing load capacity and efficiency. The derived meshing equations and performance parameters provide a foundation for further optimization and application in various mechanical systems. Future work may involve experimental validation, material selection studies, and integration into industrial gearboxes. Overall, this innovative worm gear drive represents a promising advancement in transmission technology, aligning with the ongoing pursuit of high-performance and durable mechanical components.

In conclusion, we have thoroughly examined the meshing theory of the roller enveloping end face engagement worm gear drive, from its working principles to detailed mathematical modeling. The use of coordinate transformations, differential geometry, and kinematics allowed us to derive essential formulas for meshing analysis, including contact lines, tooth surfaces, and key performance indicators. The results indicate that this worm gear drive achieves superior lubrication, reduced curvature, and enhanced rolling behavior, making it a viable solution for applications requiring high precision and longevity. As the demand for efficient and reliable worm gear drives continues to grow, such innovative designs will play a crucial role in advancing mechanical engineering practices. We encourage further research into parameter optimization, manufacturing techniques, and real-world testing to fully harness the potential of this worm gear drive configuration.