In mechanical engineering, the worm gear drive stands out as a crucial mechanism for transmitting motion and power between non-intersecting, perpendicular shafts. As an engineer, I have frequently encountered and utilized worm gear drives in various applications, from heavy machinery to precision instruments. This drive system, composed of a worm (similar to a screw) and a worm wheel, offers unique advantages that make it indispensable in many industrial settings. In this extensive analysis, I will delve into the intricacies of worm gear drives, exploring their characteristics, types, efficiency, lubrication, thermal management, and installation practices. The goal is to provide a thorough understanding that can guide practical implementation and optimization. Throughout this discussion, I will emphasize the term ‘worm gear drive’ to reinforce its importance and applicability.

The worm gear drive is primarily used for speed reduction, with typical transmission ratios ranging from 10:1 to 80:1, and even up to 1000:1 for motion transmission alone. Its ability to achieve high reduction ratios in a compact space is one of its most celebrated features. Additionally, the smooth and quiet operation due to continuous line contact between the worm and worm wheel teeth makes it suitable for environments where noise reduction is critical. Another notable aspect is the potential for self-locking when the worm’s lead angle is less than the equivalent friction angle of the materials, a property leveraged in safety-critical systems like hoists. However, these benefits come with trade-offs, such as lower efficiency compared to other gear systems, primarily due to significant sliding friction and heat generation. This often necessitates the use of expensive materials like bronze for the worm wheel to mitigate wear and tear. In this analysis, I will break down these elements systematically, employing tables and formulas to encapsulate key concepts.

One of the fundamental aspects of the worm gear drive is its distinct characteristics. To summarize, I have compiled the key features in the table below, which contrasts them with conventional gear drives. This comparison helps in understanding why the worm gear drive is chosen for specific applications despite its drawbacks.

| Characteristic | Worm Gear Drive | Typical Gear Drive |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Ratio | High (10–1000) | Moderate (1–10) |

| Noise Level | Low (smooth engagement) | Higher (discrete tooth contact) |

| Self-Locking Capability | Possible (if lead angle is small) | Rarely available |

| Efficiency | Lower (0.7–0.9 for non-self-locking) | Higher (0.95–0.98) |

| Material Cost | Often higher (bronze worm wheel) | Lower (steel or cast iron) |

| Compactness | High (due to high ratio) | Moderate |

The efficiency of a worm gear drive is a critical parameter that influences its selection and performance. The total efficiency $\eta$ of a worm gear drive can be expressed as the product of three components: the meshing efficiency $\eta_1$, the bearing efficiency $\eta_2$, and the churning efficiency $\eta_3$. Mathematically, this is represented as:

$$ \eta = \eta_1 \cdot \eta_2 \cdot \eta_3 $$

Here, $\eta_2$ and $\eta_3$ are typically in the range of 0.95 to 0.96, so the meshing efficiency $\eta_1$ dominates. For a worm gear drive with the worm as the driver, $\eta_1$ can be approximated using the formula for screw efficiency:

$$ \eta_1 = \frac{\tan \lambda}{\tan (\lambda + \rho_v)} $$

where $\lambda$ is the lead angle of the worm, and $\rho_v$ is the equivalent friction angle, defined as $\rho_v = \arctan f_v$, with $f_v$ being the coefficient of friction that depends on the sliding velocity $v_s$. The sliding velocity in a worm gear drive is given by:

$$ v_s = \frac{\pi d_1 n_1}{60 \cos \lambda} $$

where $d_1$ is the worm pitch diameter and $n_1$ is the worm rotational speed in rpm. As $v_s$ increases, $f_v$ decreases due to better oil film formation, thus improving efficiency. The lead angle $\lambda$ plays a pivotal role; efficiency generally increases with $\lambda$ up to about 27°, beyond which gains diminish. For self-locking worm gear drives, where $\lambda \leq \rho_v$, the efficiency drops below 50%, making them suitable only for intermittent or low-power applications. To provide a quick reference, I have tabulated typical total efficiency values for worm gear drives based on the number of worm threads (or starts) $z_1$.

| Drive Configuration | Worm Threads ($z_1$) | Total Efficiency ($\eta$) |

|---|---|---|

| Closed (Enclosed) | 1 | 0.70–0.75 |

| 2 | 0.75–0.82 | |

| 4 | 0.82–0.92 | |

| Open (Exposed) | 1 or 2 | 0.60–0.70 |

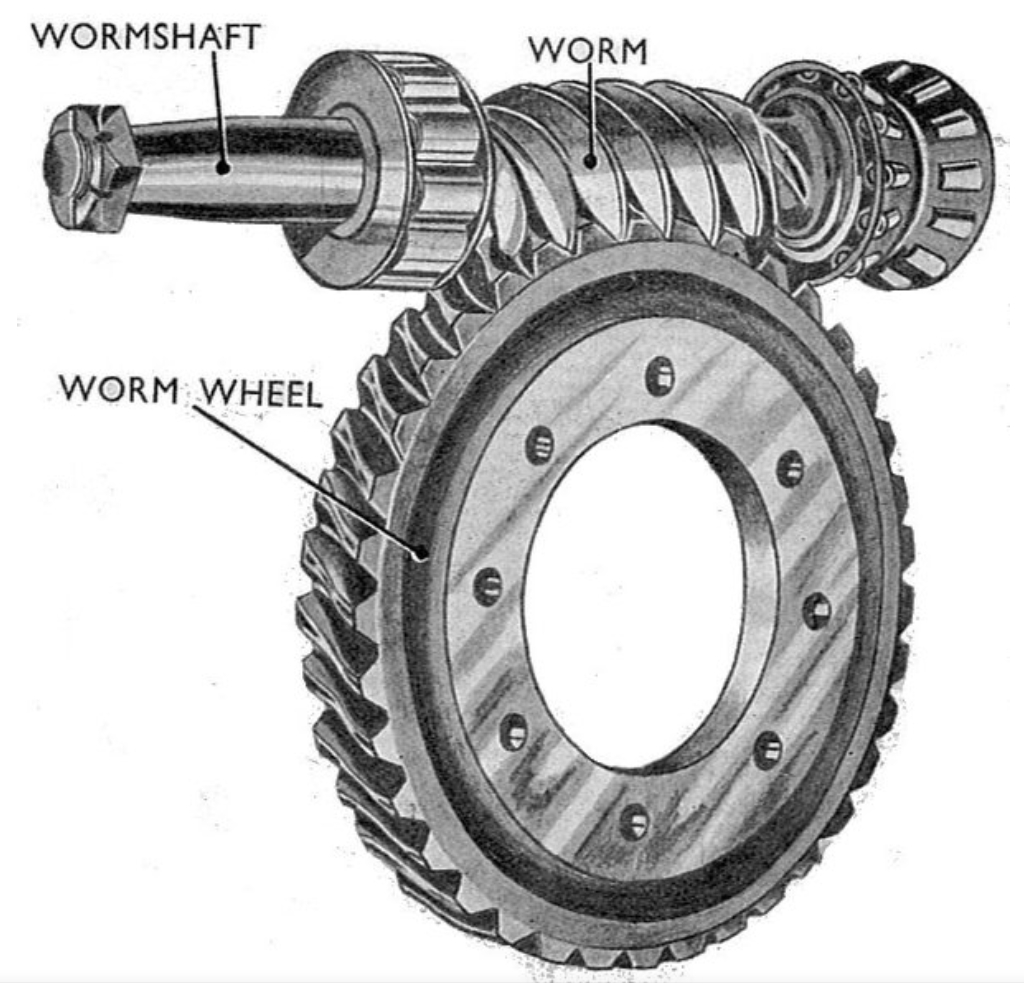

Moving on to the types and structures of worm gear drives, they can be classified based on the worm’s geometry. The primary categories include cylindrical worm gear drives, double-enveloping worm gear drives, and cone worm gear drives. Among these, cylindrical worm gear drives are the most common and are further subdivided into ordinary cylindrical worms (like the Archimedean, involute, and normal straight-line types) and arc-contact cylindrical worms. The arc-contact type offers a larger comprehensive curvature radius, leading to higher load capacity (50–100% increase) and efficiency (over 90%), but it demands precise alignment. The structural design of the worm and worm wheel also varies. Typically, the worm is integrated with the shaft (worm shaft) and made from hardened steel, while the worm wheel is often a composite structure with a bronze ring mounted on a cast iron or steel core to balance cost and performance. For clarity, I summarize the main types of worm gear drives and their attributes in the following table.

| Type of Worm Gear Drive | Key Features | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cylindrical (Ordinary) | Simple manufacturing, moderate load capacity | General machinery, conveyors |

| Cylindrical (Arc-Contact) | High load capacity, low noise, sensitive to misalignment | High-power reducers, precision equipment |

| Double-Enveloping | Very high load capacity (2–4× ordinary), efficient | Heavy-duty industrial drives, mining equipment |

| Cone | Large transmission ratio range, good lubrication, asymmetric design | Specialized machinery, variable speed drives |

Lubrication is paramount in worm gear drives due to the high sliding velocities and associated heat generation. Proper lubrication reduces friction, minimizes wear, and prevents scoring or seizure. The choice of lubricant viscosity and method depends on the sliding speed $v_s$ and load conditions. For closed worm gear drives, immersion lubrication or pressure spray lubrication is employed. In immersion lubrication, the oil level should cover the worm teeth but not exceed the center of the lowest rolling element in the bearings. When $v_s > 5 \, \text{m/s}$, pressure spray lubrication is preferred to avoid excessive churning losses. Open worm gear drives typically use high-viscosity gear oils or grease. To aid selection, I present a lubrication guideline table based on sliding velocity.

| Sliding Velocity $v_s$ (m/s) | Recommended Lubricant Viscosity (at 40°C) | Lubrication Method |

|---|---|---|

| $v_s < 2$ | High viscosity (e.g., ISO VG 460) | Immersion or grease |

| $2 \leq v_s \leq 5$ | Medium viscosity (e.g., ISO VG 220–320) | Immersion |

| $v_s > 5$ | Low viscosity (e.g., ISO VG 68–150) | Pressure spray |

The thermal balance calculation for a worm gear drive is essential to prevent overheating, which can degrade the lubricant and cause failure. The heat generated $Q_1$ (in watts) due to power losses is given by:

$$ Q_1 = P_1 (1 – \eta) \times 1000 $$

where $P_1$ is the input power in kilowatts. The heat dissipated $Q_2$ through the housing to the ambient air is:

$$ Q_2 = K_s (t_1 – t_0) A $$

Here, $K_s$ is the heat transfer coefficient (10–17 W/m²·°C for natural convection, higher with forced air), $t_1$ is the oil temperature, $t_0$ is the ambient temperature (usually 20°C), and $A$ is the effective heat dissipation area of the housing in square meters. At thermal equilibrium, $Q_1 = Q_2$, leading to the steady-state oil temperature:

$$ t_1 = \frac{1000(1 – \eta) P_1}{K_s A} + t_0 $$

This temperature must not exceed the allowable limit $[t_1]$, typically 70–90°C. If $t_1 > [t_1]$, cooling measures such as adding fins, using fans, incorporating cooling coils, or employing oil circulation systems are necessary. To illustrate, consider a worm gear drive with $P_1 = 10 \, \text{kW}$, $\eta = 0.85$, $K_s = 12 \, \text{W/m}²\cdot\text{°C}$, $A = 2 \, \text{m}²$, and $t_0 = 20°C$. Then:

$$ t_1 = \frac{1000 \times (1 – 0.85) \times 10}{12 \times 2} + 20 = \frac{1500}{24} + 20 \approx 82.5°C $$

This is within the acceptable range. However, for higher loads or poorer cooling conditions, iterative design adjustments are needed.

Installation and maintenance of worm gear drives require precision to ensure longevity and performance. During installation, the worm wheel’s mid-plane must align with the worm axis to avoid edge loading and premature wear. Adjustable shims or sleeves are used to fine-tune the worm wheel’s axial position. After assembly, a run-in period at low speed (50–100 rpm) under gradually increased load is recommended to seat the teeth properly. Any bronze transfer onto the worm should be polished off promptly. Maintenance involves regular oil changes every 2000–4000 operating hours, using the same oil grade to prevent incompatibility. Monitoring oil temperature and tooth condition is crucial; sudden rises in temperature or abnormal wear patterns indicate issues needing attention. The self-locking property of some worm gear drives adds a safety factor but also demands careful inspection to ensure it functions as intended.

In practice, the design of a worm gear drive involves multiple interdependent parameters. For instance, the center distance $a$ between worm and worm wheel axes is a key dimension that affects torque capacity and size. It can be estimated from the input torque $T_1$ and material properties using empirical formulas. The worm diameter factor $q$ (ratio of pitch diameter to module) influences stiffness and efficiency. A common design equation for cylindrical worm gear drives relates the axial module $m_x$ to the center distance:

$$ a = \frac{m_x (q + z_2)}{2} $$

where $z_2$ is the number of teeth on the worm wheel. The torque capacity $T_2$ on the worm wheel is given by:

$$ T_2 = T_1 \cdot i \cdot \eta $$

with $i = z_2 / z_1$ being the transmission ratio. These formulas, combined with stress calculations for bending and contact fatigue, form the basis of worm gear drive design. To encapsulate common design choices, I provide a table of standard module values for different center distances.

| Center Distance $a$ (mm) | Recommended Axial Module $m_x$ (mm) | Typical $q$ Range |

|---|---|---|

| 50–100 | 2–4 | 8–12 |

| 100–200 | 4–8 | 10–14 |

| 200–400 | 8–12 | 12–16 |

Another vital aspect is the material selection for worm gear drives. The worm is usually made of case-hardened steel (e.g., 16MnCr5 or 20MnCr5) to resist wear, while the worm wheel is often bronze (e.g., tin bronze CuSn12) for its anti-frictional properties. In cost-sensitive applications, cast iron or aluminum bronze may be used. The hardness difference between worm and worm wheel should be substantial to reduce adhesion. The permissible contact stress $\sigma_H$ and bending stress $\sigma_F$ are derived from material fatigue limits and are used in verification calculations. For example, the contact stress for a worm gear drive can be estimated using:

$$ \sigma_H = Z_E \sqrt{\frac{F_t}{d_1 b} \cdot \frac{i+1}{i}} $$

where $Z_E$ is the elasticity factor, $F_t$ is the tangential force, $d_1$ is the worm pitch diameter, and $b$ is the face width of the worm wheel. These stresses must remain below allowable values to ensure a safe design.

In terms of applications, the worm gear drive is ubiquitous in industries requiring high reduction ratios and compact layouts. Examples include conveyor systems, where smooth starting and stopping are essential; elevators and hoists, leveraging self-locking for safety; and precision instruments like telescopes, where quiet operation is critical. In automotive sectors, worm gear drives are found in steering mechanisms and windshield wipers. Each application imposes specific demands on the worm gear drive, such as durability, efficiency, or backlash control. For instance, in servo systems, backlash minimization is achieved through preloading or special tooth profiles. The versatility of the worm gear drive stems from its adaptability to diverse requirements through design variations.

To further illustrate the performance metrics, consider the power rating of a worm gear drive. It is often limited by thermal capacity rather than mechanical strength. The allowable input power $P_{1,\text{allow}}$ based on thermal equilibrium can be derived from the heat dissipation equation:

$$ P_{1,\text{allow}} = \frac{K_s A (t_{1,\text{max}} – t_0)}{1000(1 – \eta)} $$

where $t_{1,\text{max}}$ is the maximum allowable oil temperature. This highlights the importance of cooling in high-power worm gear drives. For example, with $K_s = 15 \, \text{W/m}²\cdot\text{°C}$, $A = 3 \, \text{m}²$, $t_{1,\text{max}} = 90°C$, $t_0 = 25°C$, and $\eta = 0.8$, we get:

$$ P_{1,\text{allow}} = \frac{15 \times 3 \times (90 – 25)}{1000 \times (1 – 0.8)} = \frac{2925}{200} \approx 14.6 \, \text{kW} $$

Thus, even if mechanically capable, the worm gear drive might be restricted to this input power without additional cooling.

In conclusion, the worm gear drive is a sophisticated mechanical system that offers unique benefits in terms of high reduction ratios, compactness, and smooth operation. However, its design and operation require careful attention to efficiency, lubrication, thermal management, and precision alignment. Through this analysis, I have explored the fundamental principles, backed by formulas and tables, to provide a comprehensive guide. Whether designing a new worm gear drive or maintaining an existing one, understanding these aspects is crucial for optimal performance and longevity. The worm gear drive continues to be a vital component in modern machinery, and its proper application can lead to significant advancements in mechanical systems. As technology evolves, materials and lubrication methods may improve, further enhancing the capabilities of worm gear drives. For now, adhering to best practices in calculation, installation, and maintenance ensures reliability and efficiency in diverse industrial contexts.

Finally, I emphasize that the worm gear drive is not a one-size-fits-all solution; its selection should be based on a thorough analysis of requirements, including load, speed, environment, and cost. By leveraging the insights shared here, engineers can make informed decisions that harness the full potential of worm gear drives. The integration of theoretical knowledge with practical experience is key to mastering this complex yet rewarding field. As I reflect on my own experiences, the worm gear drive stands as a testament to the ingenuity of mechanical design, blending simplicity with sophistication to solve real-world problems.