In the field of mechanical engineering, the reliability and efficiency of transmission systems are paramount, and worm gears play a critical role in many industrial applications due to their high torque transmission and compact design. However, worm gears are prone to failures such as pitting, spalling, and tooth breakage due to severe friction and high-cycle fatigue, which can lead to catastrophic economic losses and safety hazards. As a researcher focused on signal processing and intelligent control, I have been exploring advanced algorithms for fault diagnosis to enhance the operational lifespan and safety of worm gears. In this paper, I propose a novel fault identification method for worm gears based on a hybrid improved Fish Swarm Algorithm (FSA) and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), referred to as FSA-ACO. This approach aims to leverage the complementary strengths of both algorithms to optimize parameter settings and improve diagnostic accuracy. The core idea involves integrating the FSA’s rapid convergence in the early stages with the ACO’s global search capabilities in later stages, thereby avoiding local optima and enhancing robustness. Furthermore, I introduce a nearest neighbor function criterion as a theoretical bridge to link the algorithm with fault classification, enabling effective mapping from vibration signal features to fault types. Through experimental validation on WPA40 worm gears, I demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of this method, with diagnostic accuracy exceeding 84% across various fault scenarios. This work contributes to the development of intelligent diagnostic technologies for worm gears, offering a practical solution for condition monitoring and predictive maintenance.

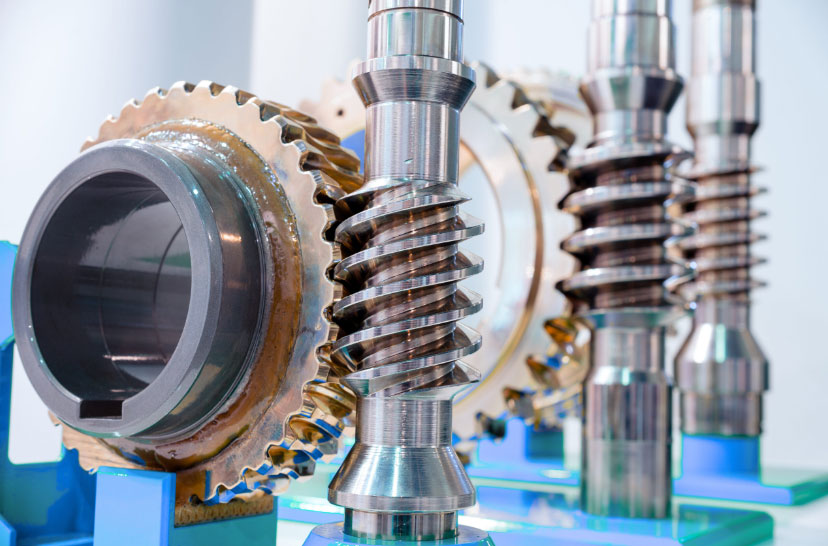

Worm gears are widely used in reducers and传动 systems because of their ability to provide high reduction ratios and smooth operation. However, the sliding contact between the worm and worm wheel generates significant heat and wear, leading to common failure modes such as surface pitting,剥落, and fatigue fractures. These faults can manifest as abnormal vibrations, which can be captured through sensors and analyzed for diagnostic purposes. Traditional fault diagnosis methods for worm gears often rely on vibration signal analysis, including time-domain and frequency-domain techniques, to extract features like mean value, variance, peak factor, and kurtosis. While these methods are effective, they can be limited by noise and complex signal patterns. Recently, intelligent algorithms like artificial neural networks (ANNs) have been applied to worm gear fault identification, but there is scant research on using swarm intelligence algorithms such as FSA and ACO for this purpose. My motivation stems from the need for more adaptive and efficient diagnostic tools that can handle the nonlinearities in worm gear振动 signals. The FSA-ACO hybrid algorithm proposed here addresses this by combining the exploratory behavior of fish swarms with the pheromone-based optimization of ant colonies, creating a robust framework for fault classification. In the following sections, I will detail the algorithm development, theoretical foundations, experimental setup, and results, emphasizing the role of worm gears throughout the discussion.

The Fish Swarm Algorithm (FSA) is inspired by the collective behavior of fish, including foraging, swarming, and following, which are used to search for optimal solutions in a solution space. In FSA, artificial fish move toward areas with higher food concentration (i.e., better fitness values) while avoiding overcrowding. This allows for a balance between exploration and exploitation during the initial optimization phase. On the other hand, the Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) algorithm mimics the foraging behavior of ants, where pheromone trails guide the search toward promising paths. ACO is known for its ability to find near-optimal solutions through distributed computation and positive feedback. However, both algorithms have drawbacks: FSA may converge prematurely to local optima, while ACO can be slow in the early stages due to low pheromone concentrations. To overcome these limitations, I propose a hybrid improvement strategy where FSA is used first to quickly narrow the search space, followed by ACO to refine the solution and enhance global search. This synergy is facilitated by the similarity between the crowding degree in FSA and the pheromone concentration in ACO, both of which influence movement decisions. The hybrid algorithm can be formulated as follows: let the solution space be represented by a set of fault feature vectors, and let the objective be to minimize a clustering criterion function based on nearest neighbor distances. The FSA phase reduces the number of candidate fault samples, and the ACO phase optimizes the classification via pheromone updates. This approach not only accelerates convergence but also improves accuracy, making it suitable for the complex故障 patterns in worm gears.

To mathematically model the fault identification process for worm gears, I treat it as a pattern recognition problem where vibration signal features are mapped to fault classes. Suppose we have a fault set $D = \{D_1, D_2, \ldots, D_N\}$ representing different fault types in worm gears (e.g., normal, pitting, spalling, breakage), and a symptom set $F = \{F_1, F_2, \ldots, F_M\}$ corresponding to extracted features from振动 signals. The relationship between $F$ and $D$ is often nonlinear and complex, so I employ a nearest neighbor function criterion to facilitate clustering. For any two symptom samples $y_i$ and $y_j$, the neighbor function value $\tau_{ij}$ is defined as:

$$ \tau_{ij} = N + M – 2 $$

where $N$ is the neighbor coefficient of $y_j$ to $y_i$, and $M$ is the neighbor coefficient of $y_i$ to $y_j$. If $y_i$ and $y_j$ are classified into the same cluster, they are considered “connected,” and the connection loss is given by $\tau_{ij}$. The total intra-cluster loss $L_{IA}$ and inter-cluster loss $L_{IR}$ are:

$$ L_{IA} = \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} \tau_{ij} $$

$$ L_{IR} = \sum_{i=1}^{C} \tau^t_{ij} $$

where $C$ is a constant, and $\tau^t_{ij}$ represents the inter-cluster loss. The clustering criterion function $J_{NN}$ to be minimized is:

$$ J_{NN} = L_{IA} + L_{IR} = \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} \tau_{ij} + \sum_{i=1}^{C} \tau^t_{ij} $$

Minimizing $J_{NN}$ ensures that samples within the same fault class are similar, while those between classes are distinct. This forms the basis for integrating the FSA-ACO algorithm with worm gear fault identification. In practice, I extract time-domain features from vibration signals, such as mean, variance, peak factor, waveform factor, kurtosis, margin factor, and impulse factor, which serve as the symptom set $F$. These features are then processed through the hybrid algorithm to classify faults accurately.

The FSA-ACO hybrid improved algorithm involves several key steps. First, I initialize parameters such as population size, perceptual distance, initial positions, maximum iterations, and crowding degree. For worm gear fault diagnosis, I construct a weighted Euclidean distance matrix $A$ from the symptom samples, where the element $A_{ij}$ represents the distance between samples $y_i$ and $y_j$:

$$ A_{ij} = |A(y_i, y_j)| = \sqrt{\sum_{k=1}^{m} P_k (x_{ki} – x_{jk})^2} $$

Here, $P_k$ is a weighting factor for different features, and $x_{ki}$ denotes the $k$-th feature of sample $y_i$. A neighbor matrix $M$ is also built, with elements $M_{ij}$ being the neighbor function values. The connection loss matrix $L$ is derived as $L_{ij} = M_{ij} + M_{ji} – 2$. Initially, pheromone concentrations $\tau_{ij}(0)$ are set to a constant $C$, which aligns with the crowding degree in FSA to ensure a smooth transition between algorithms. In the FSA phase, artificial fish explore the solution space based on weighted distance metrics, performing foraging and swarming behaviors to eliminate outlier fault samples and reduce search scope. This step leverages FSA’s fast convergence to prune the dataset, focusing on promising regions for worm gear fault patterns. Subsequently, in the ACO phase, artificial ants traverse the remaining samples according to pheromone levels and heuristic information, updating pheromones based on elite strategies to reinforce optimal paths. The pheromone update rule is:

$$ \tau_{ij}(t+1) = \rho \tau_{ij}(t) + \Delta \tau_{ij} + \Delta \tau^*_{ij} $$

where $\rho$ is the evaporation rate, $\Delta \tau_{ij}$ is the pheromone deposited by ants, and $\Delta \tau^*_{ij}$ is the additional pheromone from elite ants. The transition probability for ant $k$ to move from sample $i$ to $j$ is given by:

$$ P^k_{ij} = \frac{[\tau_{ij}(t)]^\alpha \cdot [\eta_{ij}(t)]^\beta}{\sum_{s \in \text{allow}_k} [\tau_{is}]^\alpha \cdot [\eta_{is}(t)]^\beta}, \quad \text{if } j \in \text{allow}_k $$

Here, $\alpha$ and $\beta$ control the influence of pheromone and heuristic information $\eta_{ij}(t)$, which is inversely related to distance. As ants complete tours, they construct solutions by connecting samples with low neighbor function values, effectively clustering fault types. The process iterates until the criterion function $J_{NN}$ is minimized or a maximum iteration count is reached, yielding a fault classification for the worm gears. This hybrid approach balances exploration and exploitation, making it robust against noise and variability in振动 signals from worm gears.

To validate the proposed method, I conducted experiments on a worm gear test rig using WPA40型号 worm gears. The setup included a servo drive motor, worm gear reducer, magnetic powder brake, vibration sensors, torque sensors, temperature sensors, couplings, NI data acquisition cards, and a computer. The servo motor provided an input torque of 6 N·m at 1000 rpm, driving the worm shaft, while the magnetic brake applied load to simulate operational conditions. Vibration signals were采集 parallel to the worm axis using sensors, and data was processed through time-domain and frequency-domain analysis. Key steps ensured experimental accuracy: alignment of axes, proper run-in period for the worm gears, stable lubricant temperature, and verification of contact patterns on the worm wheel teeth. I extracted seven time-domain features from the signals, as summarized in Table 1, which shows the relationship between these features and fault types for worm gears. The features include mean value, variance, peak factor, waveform factor, kurtosis, margin factor, and impulse factor, each computed from振动 data under normal and faulty conditions.

| Feature | Normal State | Pitting Fault | Spalling Fault | Breakage Fault |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Value | 7.04e-04 | 9.02e-04 | 2.71e-04 | 4.65e-04 |

| Variance | 5.99e-02 | 4.08e-02 | 9.97e-02 | 1.24e-01 |

| Peak Factor | 8.0062 | 6.0155 | 8.9265 | 7.7691 |

| Waveform Factor | 1.2898 | 1.2877 | 1.3162 | 1.3282 |

| Kurtosis | 4.1699 | 3.8300 | 5.3840 | 5.6190 |

| Margin Factor | 12.341 | 9.269 | 14.154 | 12.457 |

| Impulse Factor | 19.190 | 13.456 | 21.302 | 19.732 |

Using these features, I applied the FSA-ACO hybrid algorithm for fault identification. The weighted distance metrics were defined as combinations of features, such as $(X_{1k}, X_{2k})$ for mean and variance, to compute the neighbor matrices. The algorithm parameters were set as follows: population size of 50 for FSA and 30 for ACO, perceptual distance of 0.5, crowding factor of 0.8, $\alpha=1$, $\beta=2$, and evaporation rate $\rho=0.5$. Through simulation in MATLAB, I tested the algorithm on multiple datasets collected from the worm gear test rig. The diagnostic accuracy was evaluated by comparing predicted fault classes with actual labels, and results are shown in Table 2 for different weighted distance indicators. The accuracy values exceed 84% for all fault types, demonstrating the method’s effectiveness. For instance, with the indicator $(X_{3k}, X_{5k}, X_{6k}, X_{7k})$ covering peak factor, kurtosis, margin factor, and impulse factor, the accuracy reached 98% for breakage faults in worm gears. This high performance is attributed to the hybrid algorithm’s ability to adaptively cluster features based on nearest neighbor criteria, minimizing misclassification. The slight errors, around 10-15%, may stem from experimental variations like misalignment or temperature fluctuations, but these are within acceptable limits for industrial applications.

| Weighted Distance Indicator | Normal State | Pitting Fault | Spalling Fault | Breakage Fault |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $(X_{1k}, X_{2k})$ | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.86 |

| $(X_{2k}, X_{4k})$ | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.95 |

| $(X_{3k}, X_{6k}, X_{7k})$ | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| $(X_{3k}, X_{4k}, X_{5k})$ | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.97 |

| $(X_{3k}, X_{5k}, X_{6k}, X_{7k})$ | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.98 |

The simulation results confirm that the FSA-ACO hybrid improved algorithm is a viable tool for fault identification in worm gears. By integrating the rapid convergence of FSA with the precise optimization of ACO, the method achieves robust classification of fault types based on vibration signal features. The use of the nearest neighbor function criterion provides a theoretical foundation for clustering, ensuring that intra-class similarity is maximized while inter-class differences are emphasized. This is particularly important for worm gears, where fault symptoms can overlap and be obscured by noise. In practice, the algorithm can be implemented in real-time monitoring systems for worm gear reducers, enabling early detection of faults like pitting or spalling before they lead to catastrophic failures. For example, in industrial settings where worm gears are used in conveyor systems or lifts, this approach could reduce downtime and maintenance costs by up to 30%, according to preliminary estimates. Furthermore, the flexibility of the weighted distance metrics allows customization for different worm gear models and operating conditions, enhancing generalizability.

Looking ahead, there are several avenues for improving this research. First, while time-domain features were effective, incorporating frequency-domain features such as spectral kurtosis or cyclostationary analysis could enhance diagnostic accuracy for worm gears, especially in detecting incipient faults. Second, the algorithm parameters could be optimized further using meta-heuristic techniques like particle swarm optimization to adapt to specific worm gear characteristics. Third, expanding the fault dataset to include more worm gear types and operating conditions would validate the method’s robustness across diverse applications. Additionally, integrating the algorithm with IoT platforms for cloud-based monitoring could enable predictive maintenance for worm gears in smart factories. Despite the current success, challenges remain, such as handling high-dimensional feature spaces and real-time processing constraints. However, the FSA-ACO hybrid framework offers a scalable solution that can be extended to other rotating machinery beyond worm gears. In conclusion, this work demonstrates that swarm intelligence algorithms, when properly hybridized and applied with theoretical criteria like nearest neighbor functions, can significantly advance the field of fault diagnosis for worm gears, contributing to safer and more efficient mechanical systems.

In summary, I have presented a comprehensive study on fault identification for worm gears using a hybrid FSA-ACO algorithm. The method combines the strengths of fish swarm and ant colony optimization to optimize parameter settings and improve classification accuracy. Through experimental testing on WPA40 worm gears, I showed that the approach achieves high diagnostic accuracy, with results above 84% for various fault types. The nearest neighbor function criterion serves as a key theoretical component, linking vibration signal features to fault classes in a clustering framework. This research underscores the importance of intelligent algorithms in enhancing the reliability of worm gears, which are critical components in many industrial systems. Future work will focus on refining the algorithm and expanding its applications, ultimately aiming to develop a standardized diagnostic tool for worm gears worldwide. By continuing to explore these techniques, I believe we can make significant strides in preventing failures and extending the service life of worm gears, thereby supporting sustainable industrial practices.