In my experience with industrial machinery, worm gear reducers are pivotal components in applications requiring low-speed, high-torque power transmission. These devices are renowned for their large reduction ratios, compact design, and smooth operation, making them indispensable in sectors like metallurgy, chemical processing, packaging, and construction. However, as with any mechanical system, worm gears are prone to failures that can disrupt production and pose safety risks. Through this article, I aim to delve into the common failure modes of worm gear reducers, analyze their root causes, and propose effective maintenance strategies. I will incorporate tables and formulas to summarize key points, ensuring a comprehensive guide for engineers and technicians. The focus will remain on worm gears, a term I will emphasize throughout to highlight their significance.

To begin, let me outline the fundamental aspects of worm gear reducers. A worm gear reducer is a power transmission mechanism that utilizes a worm (a screw-like gear) and a worm wheel (a helical gear) to achieve speed reduction and torque multiplication. The worm, typically made of hardened steel, engages with the worm wheel, often fabricated from bronze or similar materials, to provide high reduction ratios in a single stage. The unique sliding contact between the worm and worm wheel results in quiet operation but also generates heat and wear, which are central to many failures. The mechanical advantage of worm gears can be expressed using the gear ratio formula: $$ i = \frac{N_w}{N_g} $$ where \( i \) is the reduction ratio, \( N_w \) is the number of threads on the worm (often referred to as starts), and \( N_g \) is the number of teeth on the worm wheel. For instance, a single-start worm engaging with a 50-tooth worm wheel yields a ratio of 50:1, enabling substantial torque output. This characteristic makes worm gears ideal for heavy-duty applications, but it also necessitates careful design and maintenance to mitigate issues like inefficiency and thermal buildup.

The structural integrity of worm gear reducers, such as the RV series, is crucial for reliable performance. These units typically consist of a cast aluminum alloy housing for lightweight and heat dissipation, along with precision components like bearings, seals, and shafts. Below is a table summarizing the key components and their functions in a standard RV series worm gear reducer:

| Component | Material/Type | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Worm (Worm Gear) | Carbon steel (e.g., 45 steel) or alloy steel (e.g., 20CrMnTi) | Input driver that transmits motion via helical threads; hardened for wear resistance. |

| Worm Wheel (Worm Gear) | Bronze (e.g., ZCuSn10P1) or zinc-aluminum alloy (e.g., ZA27) | Output gear that meshes with the worm to reduce speed and increase torque; designed for durability. |

| Housing (Box Body) | Cast aluminum alloy (e.g., ZL401) | Encloses components, provides structural support, and aids in heat dissipation. |

| Bearings | Roller bearings (e.g., cylindrical roller bearings) | Support rotating shafts, minimize friction, and maintain alignment of worm and worm wheel. |

| Oil Seals | Nitrile rubber or fluororubber | Prevent lubricant leakage and contamination; critical for maintaining oil integrity. |

| Flange | Steel or cast iron | Connects the reducer to input sources like motors, ensuring secure mounting. |

| Oil Plug (Oil Drain) | Steel with sealing thread | Allows for lubricant drainage and replacement during maintenance cycles. |

Understanding the configuration of worm gears is essential, as it directly influences failure modes. For example, the worm and worm wheel interaction involves complex kinematics, where the sliding velocity \( v_s \) can be calculated as: $$ v_s = \frac{\pi d_w n_w}{60 \cos \lambda} $$ where \( d_w \) is the worm pitch diameter, \( n_w \) is the worm rotational speed in RPM, and \( \lambda \) is the lead angle of the worm. This sliding action, while enabling smooth torque transmission, also generates frictional heat that must be managed to prevent overheating. The efficiency of worm gears, often lower than other gear types due to this sliding, is approximated by: $$ \eta = \frac{\tan \lambda}{\tan (\lambda + \phi)} $$ where \( \phi \) is the friction angle dependent on lubrication and material pairing. Typically, efficiencies range from 50% to 90%, with higher ratios leading to more heat generation—a key factor in failures like overheating and wear. In practice, I have observed that selecting appropriate materials, such as zinc-aluminum alloys for worm wheels, can enhance durability by reducing wear rates compared to traditional bronze, as shown in studies where wear resistance improves by 3-5 times.

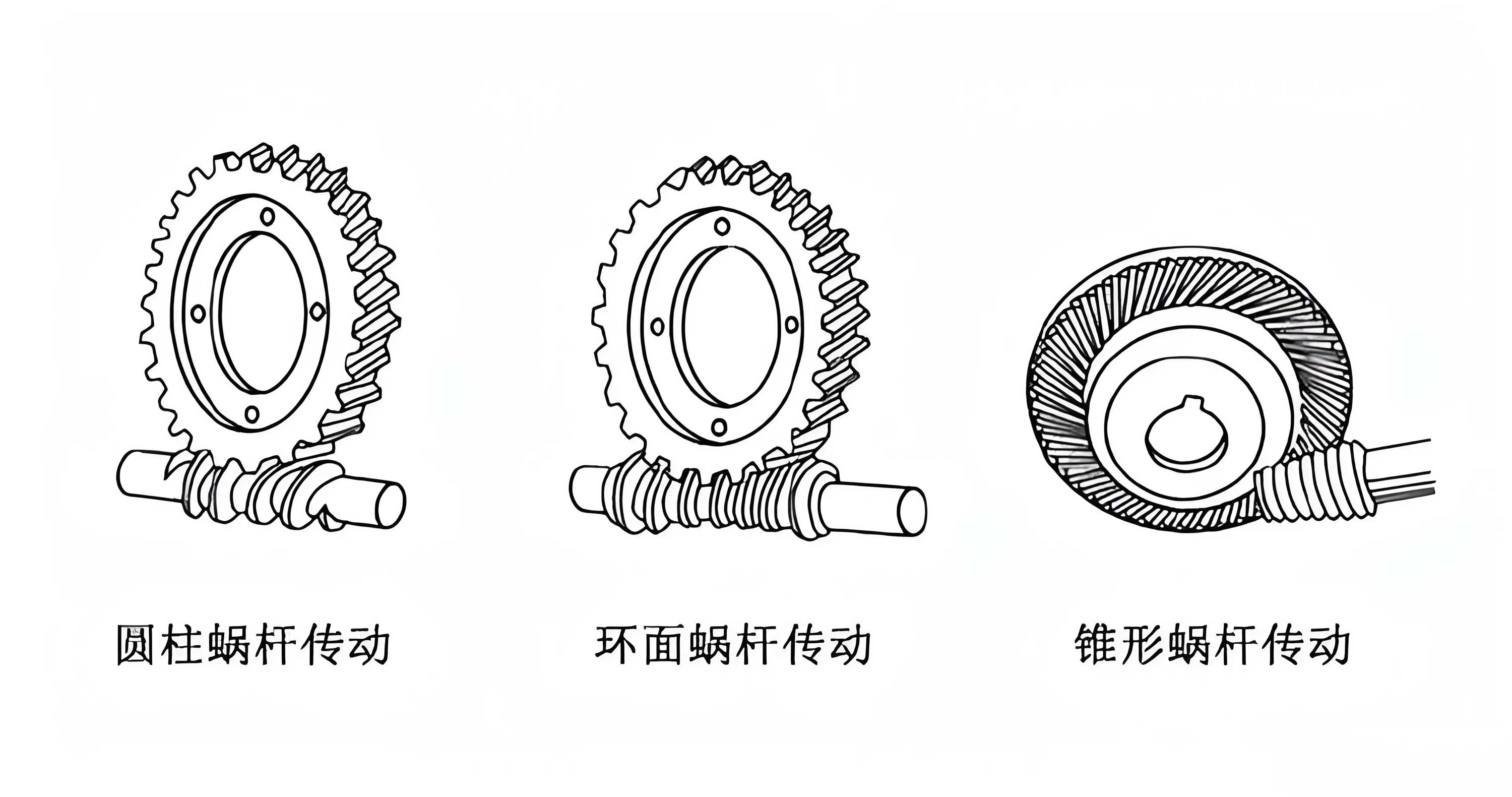

Moving on, worm gear reducers can be classified based on worm geometry, which affects their performance and failure tendencies. The primary types include cylindrical worm gears (e.g., Archimedean, involute), double-enveloping worm gears (toroidal), and cone worm gears. Each type has distinct advantages; for instance, double-enveloping worm gears offer higher load capacity due to increased contact area, but they may be more susceptible to misalignment issues. To illustrate, here is a comparison table of common worm gear types:

| Worm Gear Type | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications | Common Failure Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archimedean Worm Gears | Straight profile in axial section; simple manufacturing; moderate efficiency. | General machinery, conveyors | Wear due to high sliding friction; overheating at high loads. |

| Involute Worm Gears | Curved profile for smoother engagement; higher precision and efficiency. | High-speed drives, precision equipment | Noise and vibration if not properly aligned; oil leakage from seals. |

| Double-Enveloping Worm Gears | Worm and wheel wrap around each other; excellent load distribution. | Heavy industrial presses, mining equipment | Complex assembly leading to installation errors; thermal expansion issues. |

| Cone Worm Gears | Conical shape for multiple tooth contact; high reduction ratios. | Specialized actuators, aerospace | Lubrication challenges in confined spaces; wear on tapered surfaces. |

In all these worm gear configurations, material selection plays a critical role in mitigating failures. The worm, often made of hardened steels like 45 steel (hardness 220-300 HBS) or case-hardened alloys like 20CrMnTi (hardness 56-62 HRC), must resist wear while engaging with softer worm wheel materials. Common worm wheel materials include tin bronze (ZCuSn10P1) for high-sliding speeds and aluminum bronze (ZCuAl10Fe3) for cost-effective applications. Recently, zinc-aluminum alloys like ZA27 have gained popularity as alternatives, offering comparable wear resistance to bronze at lower costs. The wear rate \( W \) in worm gears can be modeled using the Archard equation: $$ W = k \frac{F_n L}{H} $$ where \( k \) is the wear coefficient (dependent on materials and lubrication), \( F_n \) is the normal load, \( L \) is the sliding distance, and \( H \) is the material hardness. By optimizing these parameters, failures related to premature wear can be minimized.

Now, let me delve into the common failure types of worm gear reducers, which I categorize into five main areas: overheating, oil leakage, vibration, wear, and abnormal noise. Each failure has specific causes and remedies, which I will detail with tables and formulas for clarity.

Overheating in Worm Gear Reducers: Overheating is a prevalent issue in worm gears, often signaled by elevated housing temperatures or thermal shutdowns. The primary causes include misalignment, overloading, inadequate lubrication, and environmental factors. From my observations, overheating can reduce lubricant viscosity, accelerate wear, and even lead to thermal degradation of components. The heat generation \( Q \) in a worm gear reducer can be estimated using: $$ Q = P_{loss} = P_{in} (1 – \eta) $$ where \( P_{in} \) is the input power and \( \eta \) is the efficiency. For instance, if a reducer with 70% efficiency handles 10 kW input, the heat dissipated is 3 kW, which must be managed through cooling or design. Below is a table summarizing causes and solutions for overheating in worm gears:

| Cause of Overheating | Description | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Misalignment with Driver/Driven Machine | Improper coupling leads to increased friction and heat. | Realign shafts using dial indicators; ensure parallel and angular tolerance within 0.05 mm. |

| Excessive Load (Overloading) | Operating beyond rated torque causes higher frictional losses. | Reduce load to within nameplate specifications; consider upgrading to a larger worm gear unit. |

| Inadequate Lubrication | Low oil level or wrong viscosity increases metal-to-metal contact. | Refill with correct ISO VG lubricant per manufacturer guidelines; monitor oil levels regularly. |

| Poor Ventilation or High Ambient Temperature | Insufficient heat dissipation from the housing. | Install cooling fans or heat sinks; relocate reducer to a cooler environment if possible. |

| Worm and Worm Wheel Material Incompatibility | High friction pairing generates excess heat. | Switch to materials with lower friction coefficients, e.g., using ZA27 alloy for the worm wheel. |

To prevent overheating, I recommend implementing thermal monitoring, such as infrared thermography, and calculating the thermal equilibrium using: $$ T_{eq} = T_{amb} + \frac{Q}{hA} $$ where \( T_{eq} \) is the equilibrium temperature, \( T_{amb} \) is ambient temperature, \( h \) is the heat transfer coefficient, and \( A \) is the surface area of the housing. For worm gears in continuous operation, maintaining \( T_{eq} \) below 90°C is advisable to avoid oil breakdown.

Oil Leakage in Worm Gear Reducers: Oil leakage compromises lubrication, leading to increased wear and potential failure. Common leakage points include seals, gaskets, and drain plugs. In worm gears, the dynamic sealing at the worm shaft is particularly vulnerable due to rotational forces. Causes range from seal wear to improper installation. The leakage rate \( \dot{V} \) can be approximated by the orifice equation for viscous fluids: $$ \dot{V} = C_d A \sqrt{\frac{2 \Delta P}{\rho}} $$ where \( C_d \) is the discharge coefficient, \( A \) is the leak area, \( \Delta P \) is the pressure differential, and \( \rho \) is the oil density. However, in practice, leakage is often due to mechanical issues. Here’s a table outlining oil leakage causes and fixes:

| Cause of Oil Leakage | Description | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Worn Oil Seals | Seal lip degradation from aging, heat, or abrasive particles. | Replace seals with high-temperature resistant types (e.g., fluororubber); ensure shaft surface finish ≤ 0.8 µm Ra. |

| Damaged Housing or Gaskets | Cracks or deformed flanges allow oil seepage. | Repair housing with epoxy seals or replace gaskets; torque bolts evenly to specified values. |

| Loose Drain Plug or Fittings | Improper tightening leads to gradual leaks. | Apply thread sealant and tighten to torque specs; use magnetic plugs for debris detection. |

| Excessive Internal Pressure | Heat buildup causes oil expansion and pressure rise. | Install breather vents to equalize pressure; avoid overfilling oil beyond recommended level. |

| Shaft Surface Damage | Scratches or corrosion on the worm shaft compromise seal contact. | Polish shaft or apply sleeve repairs; use hardened shafts for longevity in worm gear systems. |

Regular inspection of seals and housing integrity is crucial. For worm gears, I advise checking oil seals every 6 months and using synthetic lubricants with anti-leak additives to reduce seepage.

Vibration in Worm Gear Reducers: Vibration indicates imbalance, misalignment, or component wear, and it can accelerate failures in worm gears. Excessive vibration leads to noise, bearing fatigue, and even structural cracks. The vibration frequency \( f_v \) often correlates with rotational speeds: $$ f_v = \frac{n}{60} \times N $$ where \( n \) is the RPM and \( N \) is the number of teeth or defects. For example, a worm wheel with 50 teeth at 100 RPM might exhibit vibrations at 83.3 Hz. Common causes include unbalanced rotors, worn bearings, and gear mesh issues. Below is a table for vibration analysis in worm gears:

| Cause of Vibration | Description | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Misalignment of Input/Output Shafts | Angular or parallel misalignment induces cyclic forces. | Laser align shafts to within 0.02 mm; use flexible couplings to absorb minor misalignments. |

| Worn or Damaged Bearings | Bearing fatigue causes play and irregular motion. | Replace bearings with precision grades (e.g., ABEC 3); ensure proper preload and lubrication. |

| Unbalanced Worm or Worm Wheel | Mass asymmetry generates centrifugal forces. | Dynamic balance components to ISO 1940 G6.3 standard; check for debris or damage. |

| Loose Mounting Bolts or Foundations | Insecure fixation amplifies vibrations. | Torque all bolts to manufacturer specs; use vibration-damping pads under the reducer. |

| Gear Mesh Irregularities (e.g., Tooth Wear) | Uneven contact patterns cause pulsating vibrations. | Inspect and replace worn worm gears; adjust backlash to 0.1-0.2 mm per design. |

To quantify vibration severity, I often use the RMS velocity \( v_{rms} \) measured in mm/s, with acceptable levels below 4.5 mm/s for worm gears as per ISO 10816. Implementing vibration monitoring systems can provide early warnings for maintenance.

Wear in Worm Gear Reducers: Wear is the gradual material loss on worm and worm wheel surfaces, ultimately leading to inefficiency and failure. In worm gears, wear is exacerbated by high sliding friction and inadequate lubrication. The wear volume \( V_w \) over time can be expressed as: $$ V_w = K’ P v_s t $$ where \( K’ \) is a material-dependent constant, \( P \) is the contact pressure, \( v_s \) is the sliding velocity, and \( t \) is time. Common wear mechanisms include abrasive wear from contaminants and adhesive wear from metal-to-metal contact. Here’s a table detailing wear causes and mitigation:

| Cause of Wear | Description | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient or Degraded Lubrication | Low oil film thickness allows direct contact. | Use extreme-pressure (EP) lubricants with additives like MoS2; change oil annually or per operating hours. |

| Contamination (Dust, Metal Particles) | Abrasive particles accelerate surface degradation. | Install filtration systems; use magnetic plugs; ensure housing seals are intact. |

| Overloading Beyond Design Limits | High contact pressures exceed material yield strength. | Operate within rated torque; consider redesign with higher-capacity worm gears if needed. |

| Material Fatigue or Hardness Mismatch | Soft worm wheel materials wear faster against hard worms. | Select matched material pairs (e.g., hardened steel worm with bronze wheel); apply surface treatments like nitriding. |

| High Operating Temperatures | Heat reduces lubricant film strength and material hardness. | Implement cooling measures; monitor temperature to stay below 80°C for standard oils. |

To combat wear in worm gears, I recommend periodic oil analysis to detect wear metals and using advanced materials like polymer-composite coatings on worm wheels to reduce friction coefficients.

Abnormal Noise in Worm Gear Reducers: Unusual noises, such as grinding or whining, often signal underlying issues in worm gears. Noise can stem from meshing problems, bearing defects, or lubrication issues. The sound pressure level \( L_p \) in decibels can be related to vibrational energy: $$ L_p = 20 \log_{10} \left( \frac{p}{p_0} \right) $$ where \( p \) is the sound pressure and \( p_0 \) is the reference pressure (20 µPa). In worm gears, noise frequencies often align with tooth engagement rates. Below is a table for noise diagnosis:

| Cause of Abnormal Noise | Description | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Improper Gear Meshing (Backlash Issues) | Too tight or loose mesh causes impact noises. | Adjust backlash to specifications (typically 0.05-0.15 mm for precision worm gears); use shims if necessary. |

| Damaged or Worn Bearings | Bearing defects produce rhythmic clicking or rumbling. | Replace bearings and ensure proper lubrication; check for corrosion or overloading. |

| Inadequate Lubrication (Starved Gears) | Dry contact increases friction noise. | Refill with recommended oil; consider automatic lubrication systems for consistent supply. |

| Foreign Objects or Debris in Gear Mesh | Particles cause intermittent crunching sounds. | Disassemble and clean worm gears; inspect for damage; improve sealing against contaminants. |

| Resonance from Structural Components | Natural frequencies match operational vibrations. | Add stiffeners to housing; use damping materials; alter mounting to shift resonant frequencies. |

For noise reduction in worm gears, I suggest using helical worm designs for smoother engagement and conducting acoustic emissions testing during maintenance to pinpoint sources.

Beyond specific failures, proactive maintenance is key to extending the life of worm gear reducers. Based on my experience, I have compiled a set of maintenance guidelines that emphasize regular checks and preventive actions. Worm gears, given their sliding nature, require diligent attention to lubrication and alignment. Here are essential practices:

- Lubrication Management: Use the correct lubricant type (e.g., ISO VG 320 for most worm gears) and maintain oil levels between minimum and maximum marks. The oil change interval can be derived from the operating hours: $$ T_{change} = \frac{C}{n L_h} $$ where \( C \) is a constant (e.g., 10,000 for synthetic oils), \( n \) is the speed factor, and \( L_h \) is the load factor. For instance, under heavy loads, change oil every 2,000 hours.

- Alignment and Mounting: Ensure precise alignment between the reducer and connected equipment using laser tools. Misalignment tolerance should not exceed 0.05 mm per meter of shaft separation for worm gears.

- Temperature Monitoring: Install temperature sensors to track housing temperature. If temperatures exceed 70°C above ambient, investigate cooling options like fan kits or heat exchangers.

- Seal and Gasket Inspection: Check oil seals every 6 months for leaks or hardening. Replace seals proactively if the reducer has been idle for over 4 months, as rubber can degrade without lubrication.

- Vibration and Noise Analysis: Conduct quarterly vibration checks using handheld meters. Record baseline readings and investigate deviations above 20% increase.

- Load Verification: Avoid overloading by installing torque limiters or using amperage monitoring on drive motors. The actual torque \( \tau \) can be estimated from motor power: $$ \tau = \frac{9550 P}{n} $$ where \( P \) is power in kW and \( n \) is output speed in RPM.

Implementing a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) can schedule these tasks efficiently. For worm gears in harsh environments, I recommend more frequent inspections—perhaps monthly—to catch issues early.

In conclusion, worm gear reducers are vital components that demand careful operation and maintenance to prevent common failures like overheating, leakage, vibration, wear, and noise. Through this discussion, I have highlighted the importance of understanding worm gear mechanics, material science, and failure analysis. By applying the tables and formulas provided, engineers can diagnose issues accurately and implement targeted solutions. Regular maintenance, coupled with advanced monitoring techniques, will ensure that worm gears deliver reliable performance across various industries. As technology evolves, innovations in materials and design may further reduce failure rates, but the fundamentals of proper alignment, lubrication, and load management will remain cornerstone practices for anyone working with these essential devices.