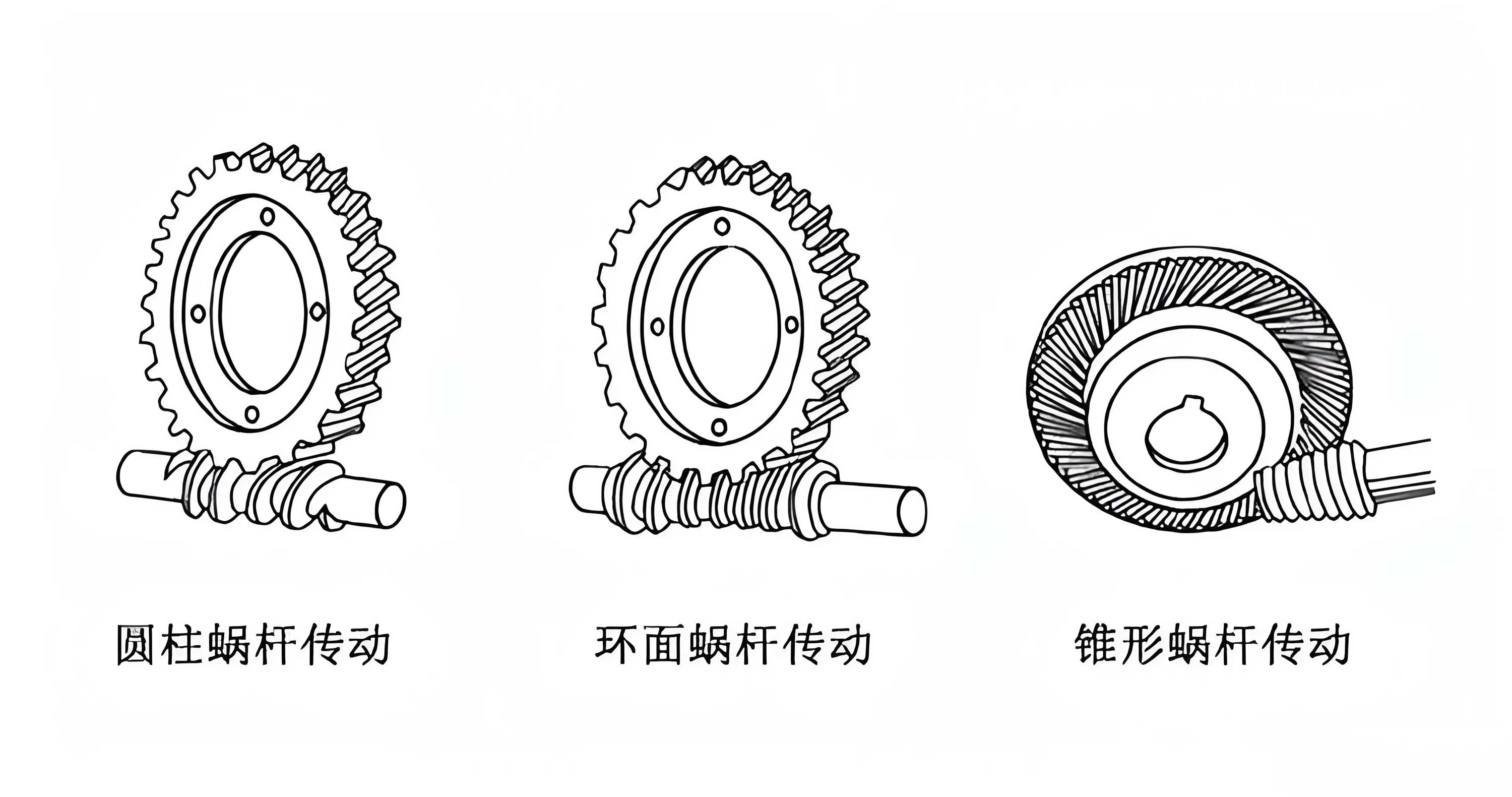

Worm gear drives are extensively utilized in mechanical systems requiring significant speed reduction within a compact design envelope, such as reducers for valve actuators in industrial applications. Their advantages, including high transmission ratios, smooth operation, and self-locking potential, make them indispensable in power transmission. The design and validation process for these critical components traditionally involves significant time and cost, particularly in achieving precise geometry for optimal meshing performance. This work details a comprehensive methodology for the accurate modeling and subsequent multi-physics analysis of a worm gear pair, demonstrating a streamlined workflow from digital design to physical validation.

Common approaches for modeling worm gears include using gear toolboxes within CAD software like Creo or SolidWorks, or dedicated gear generators like KiSSsoft. While convenient, automated toolboxes can sometimes yield models with improper meshing when assembled. Dedicated generators offer high precision but may limit later design modifications and integration into broader product development workflows. To overcome these limitations and achieve a highly accurate, flexible model suitable for advanced simulation, we employed CATIA software for the parametric and precise geometric construction of a worm gear set intended for a secondary reduction stage in a mining valve actuator gearbox.

Geometric Modeling Workflow in CATIA

The modeling process begins with the fundamental geometric parameters of the worm and worm gear. The specifications for the ZI-type (ZI stands for ZI – Zahnstangen-Involute, a German standard for involute helicoid worm) worm gear pair are listed in the table below.

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | ZI | Worm Reference Diameter, d1 (mm) | 20.00 |

| Center Distance, a (mm) | 46.00 | Worm Tip Diameter, da1 (mm) | 23.6 |

| Transmission Ratio, i | 40.00 | Worm Root Diameter, df1 (mm) | 19.68 |

| Number of Worm Threads, Z1 | 1 | Worm Lead Angle, γb (°) | 5.14 |

| Number of Worm Gear Teeth, Z2 | 40 | Worm Face Width, b1 (mm) | 25 |

| Module, m (mm) | 1.80 | Worm Gear Reference Diameter, d2 (mm) | 72 |

| Normal Pressure Angle, αn (°) | 20 | Worm Gear Root Diameter, df2 (mm) | 67.68 |

| Worm Gear Profile Shift Coefficient, x2 | -0.1 | Worm Gear Addendum, ha2 (mm) | 1.62 |

From these primary parameters, the fundamental force and kinematic data were calculated, as summarized in the following table, providing essential inputs for subsequent analyses.

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal Worm Torque, T1 (N·m) | 0.80 | Worm Gear Radial Force, Fr2 (N) | 342.06 |

| Nominal Worm Gear Torque, T2 (N·m) | 32.60 | Sliding Velocity, Vs (m/s) | 0.76 |

| Worm Tangential Force, Ft1 (N) | 81.71 | Worm Rotational Speed, n1 (rpm) | 723.00 |

| Worm Axial Force, Fx1 (N) | 907.77 | Worm Gear Rotational Speed, n2 (rpm) | 18.08 |

| Worm Radial Force, Fr1 (N) | 342.06 | Worm Pitch Line Velocity, v1 (m/s) | 0.76 |

| Worm Gear Tangential Force, Ft2 (N) | 907.77 | Worm Gear Pitch Line Velocity, v2 (m/s) | 0.07 |

| Worm Gear Axial Force, Fx2 (N) | 81.71 |

Worm Modeling: The worm model was created using the helical sweep function. First, the axial profile of the ZI worm was precisely sketched based on its defined parameters. A helix with a pitch equal to the worm’s axial pitch was then constructed. Sweeping the profile along this helix generates the precise worm thread surface. Additional manufacturing features such as chamfers and keyways were added to complete the worm model.

Worm Gear Modeling: Creating the conjugate worm gear tooth form is more complex. We utilized the DMU Kinematics simulator within CATIA to simulate the generating process, where the modeled worm acts as the hob cutter. By defining a kinematic mechanism that replicates the relative motion between the hob and the gear blank, the software calculates the envelope of the worm’s movement. This envelope data, representing the family of surfaces swept by the worm, is then processed to construct the precise tooth flank of the worm gear. This method ensures perfect theoretical conjugacy between the worm and worm gear teeth.

Assembly and Verification: The individually modeled worm and worm gear were assembled in CATIA’s Assembly Design module. The interference detection tool confirmed no geometric clashes. The meshing clearance was measured at the contact interface, with a maximum total clearance of 0.027 mm. According to the GB/T 10089-2018 standard, the single-flank composite deviation for an accuracy grade 8 worm gear pair should be less than 0.064 mm. Therefore, the modeled clearance meets this requirement, validating the geometric accuracy of the modeling approach.

Finite Element Analysis of Worm Gear Contact

To evaluate the structural performance and contact stress distribution under load, the assembled CATIA model was imported into ANSYS for static structural analysis. Key steps included material property assignment, application of realistic boundary conditions, and high-fidelity meshing.

| Component | Material | Density (kg/m³) | Poisson’s Ratio | Elastic Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worm | 42CrMo | 7850 | 0.28 | 212 |

| Worm Gear | QAL10-4-4 | 7500 | 0.34 | 114 |

Boundary conditions simulated a locked-output scenario. The worm was constrained to rotate 5° clockwise about its axis while all other degrees of freedom were fixed. A resisting torque of 32 N·m was applied to the worm gear. A fine mesh of tetrahedral elements, totaling over 930,000 elements, ensured convergence of contact stresses. The analysis revealed the contact stress distribution on the tooth surfaces. The maximum contact stress was found to be approximately 241.36 MPa, located near the root area of the worm gear teeth, indicating the region of highest loading during mesh engagement.

Dynamic Analysis Using ADAMS

While FEA provides stress under a static or quasi-static condition, dynamic analysis captures the time-varying forces and impacts during operation. The model was transferred to ADAMS for multi-body dynamics simulation.

Rigid-Body Dynamics Analysis

In the initial analysis, both the worm and worm gear were treated as rigid bodies. A critical aspect of dynamic contact simulation in ADAMS is the proper definition of the contact force model, which is based on Hertzian elastic impact theory. For two bodies in contact, the normal force \( F_n \) is related to the penetration depth \( \delta \) by:

$$ F_n = K \delta^{n} $$

where \( K \) is the contact stiffness coefficient and \( n \) is the force exponent (typically 1.5 for metals). The stiffness coefficient \( K \) is derived from material properties and geometry:

$$ K = \frac{4}{3} R^{1/2} E^{*} $$

The equivalent radius \( R \) and equivalent modulus \( E^{*} \) are calculated as:

$$ \frac{1}{R} = \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} $$

$$ \frac{1}{E^{*}} = \frac{1 – \mu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \mu_2^2}{E_2} $$

where \( R_1, R_2 \) are the contact radii (approximated by the pitch radii of the worm and worm gear), and \( \mu_1, \mu_2, E_1, E_2 \) are the Poisson’s ratios and Elastic moduli of the worm and worm gear materials, respectively. Substituting the values yields \( K \approx 3.08 \times 10^{5} \, \text{N/mm}^{1.5} \). A damping coefficient of 40 N·s/mm was determined through iterative simulations to minimize numerical error. A step function was used to apply the 32 N·m load torque smoothly over 0.5 seconds to avoid numerical instability. Simulations were run with worm input speeds of 1.3, 2.6, and 3.9 revolutions per second (rps). The resulting meshing force profiles showed an initial impact peak followed by steady-state oscillation around an average value. Key results are summarized below:

| Worm Speed (rps) | Avg. Worm Gear Speed, ω (°/s) | Max Meshing Force, F_max (N) | Avg. Meshing Force, F_avg (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.3 | 11.62 | 677.49 | 621.97 |

| 2.6 | 23.60 | 677.69 | 621.88 |

| 3.9 | 35.18 | 677.87 | 621.72 |

The analysis shows that the average meshing force remains remarkably consistent across different speeds, hovering around 622 N, which aligns well with the theoretically derived forces. The frequency of force oscillation increased proportionally with the worm speed, corresponding to a higher tooth engagement frequency.

Rigid-Flexible Coupled Dynamics Analysis

To obtain more realistic stress results within a dynamic framework, a rigid-flexible coupled analysis was performed. The worm and worm gear geometries were converted into flexible bodies by performing a modal analysis in ANSYS. The first six natural modes were extracted, with the first natural frequency being 874 Hz, confirming the bodies are sufficiently stiff for the operating frequency range. The resulting Modal Neutral Files (MNF) were imported into ADAMS. The same contact parameters, constraints, and loading were applied to these flexible bodies. The computed meshing forces from the rigid-flexible analysis were very close to those from the pure rigid-body analysis, as shown in the comparison below, but exhibited more high-frequency vibrational content, which is more physically accurate.

| Analysis Model | Max Meshing Force, F_max (N) | Avg. Meshing Force, F_avg (N) |

|---|---|---|

| Rigid-Body | 677.49 | 621.97 |

| Rigid-Flexible | 686.64 | 622.90 |

A significant advantage of the rigid-flexible coupled analysis is the ability to extract dynamic stress histories. The contact stress at the tooth root of three consecutive worm gear teeth was monitored throughout the engagement cycle. The maximum dynamic root stress was found to be 228.56 MPa. This value is in close agreement with the 241.36 MPa maximum contact stress from the static FEA, with a deviation of only about 5.3%. The stress-time histories for the three teeth showed phased peaks corresponding to their entry into and exit from the meshing zone, accurately reflecting the load-sharing behavior of the worm gear teeth.

Experimental Validation and Testing

The digital models were directly used to generate CNC machining code via CATIA’s machining module. A worm was manufactured on a CNC lathe, and its mating worm gear was produced on a machining center, both targeting an accuracy grade of 8. The physical worm gear assembly was tested on a dedicated worm gear testing machine. The primary validation checks were radial runout and contact pattern.

Radial Runout Test: The average radial runout measured during rotation was 0.024 mm. The GB/T 10089-2018 standard specifies a maximum permissible radial runout of 0.030 mm for a grade 8 worm gear pair, confirming the manufactured components met this criterion.

Contact Pattern Test: The worm thread was coated with a marking compound (red lead paste) and rotated against the worm gear. The resulting contact pattern on the worm gear teeth was examined. The pattern was located in the mid-region of the tooth flank, slightly towards the outlet side. The contact area ratio was measured to be approximately 70% along the tooth height and 60% along the tooth length. The standard requires a minimum of 55% and 50% respectively for a grade 8 pair, confirming excellent meshing quality.

Full Reducer Endurance Test: The worm gear pair was integrated into the complete four-stage valve actuator reducer. The entire unit underwent a rigorous accelerated life test on a comprehensive test bench under lubricated conditions. The test simulated extreme duty cycles, operating continuously for 24 hours per day with frequent starts under full load (58 kN). After accumulating 1,200 hours of operation—equivalent to a significant portion of the target service life—the reducer was disassembled for inspection. The worm and worm gear teeth showed no visible signs of pitting, wear, or fatigue damage, successfully meeting the partner enterprise’s durability requirements.

Conclusion

This work presented an integrated digital engineering workflow for worm gear design and validation. The methodology centered on generating a precise geometric model of a worm gear pair using advanced simulation techniques within CATIA software, ensuring perfect theoretical conjugacy. This accurate model served as a robust digital twin, enabling seamless transition to various physics-based analyses. Finite Element Analysis in ANSYS provided detailed static contact stress distributions. Dynamic analysis in ADAMS, both rigid-body and rigid-flexible coupled, yielded time-history data for meshing forces and dynamic stresses. The strong correlation between the FEA contact stress (241.36 MPa) and the dynamic root stress from rigid-flexible analysis (228.56 MPa), with a deviation of only 5.3%, cross-validates both simulation approaches. Furthermore, the physical prototypes manufactured directly from the digital models demonstrated excellent meshing characteristics in standardized tests and passed a demanding full-scale endurance test. The results conclusively demonstrate that the proposed CATIA-based modeling method for worm gears is accurate, efficient, and reliable. It provides a powerful reference framework that can significantly shorten design cycles, reduce prototyping costs, and enhance product confidence in the development of power transmission systems utilizing worm gear drives.