In my extensive experience in manufacturing and mechanical design, I have often encountered the critical challenge of finishing roller passes for high-frequency welded pipe machines. These rollers, essential tools that induce plastic deformation in metal during rolling, are subjected to severe wear, thermal fatigue, and significant rolling forces. Their precision directly impacts product quality, making the finishing process—particularly the turning of the成型槽—one of the most demanding and accuracy-sensitive operations in the entire production line. Traditionally, this task relied on manual worm gear systems, which I found to be fraught with inconsistencies and inefficiencies. Driven by the need for higher quality and productivity, I embarked on designing and researching an automatic worm gear turning device, a system that fundamentally transforms how these crucial components are machined.

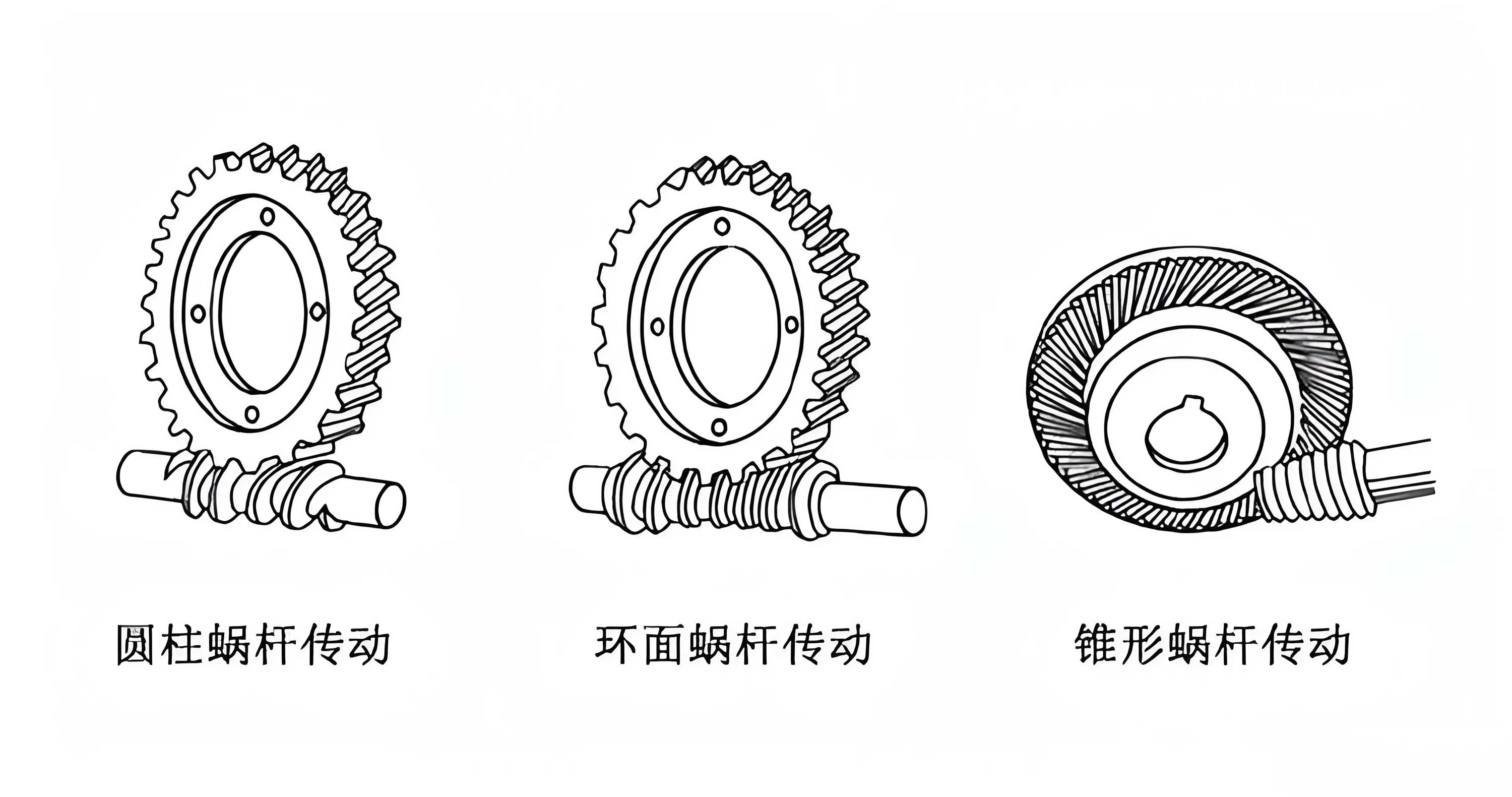

The roller, as the core tool, must maintain impeccable geometric accuracy and surface finish. Any deviation in圆度 (roundness) or excessive surface roughness leads to defective products, necessitating rework or replacement, which halts production and inflates costs. The成型槽’s complex contour, often a precise arc, requires a turning method that can trace a perfect circular path. For years, the industry standard involved a worm and worm gear副 (worm gears) mechanism operated manually via a handwheel. While mechanically sound in principle, this method places immense reliance on the operator’s skill and endurance. I have observed firsthand how this human dependency introduces variability. The hand-cranked feed of the worm gears leads to non-uniform tool movement, resulting in inconsistent roundness across the workpiece and visible tool marks that degrade surface integrity. Furthermore, maintaining coordination over long periods is physically and mentally taxing for the operator, limiting sustainable production rates and requiring highly trained personnel. The need for multiple finishing passes and subsequent polishing to achieve acceptable roughness further drags down efficiency. These limitations underscored the urgent need for an automated solution centered around the reliable motion control of worm gears.

My design philosophy was to retain the fundamental kinematic advantage of the worm gear副 while eliminating human intervention from the feed motion. The worm gears provide an excellent means of converting rotary motion into precise, controlled angular displacement of a tool, ideal for generating arcs. The challenge was to achieve this control programmatically. The resulting automatic worm gear turning device replaces the manual handwheel with an electromechanical drive system. The core assembly consists of a driven worm wheel心轴 (spindle) holding the cutting tool, a worm shaft engaged with it, a motor to drive the worm, and a control unit. This setup ensures that the tool tip’s motion is governed purely by the rotational input to the worm, decoupling it from operator inconsistency.

The working principle is elegantly simple yet highly effective. Upon initiation, the controller activates the drive motor. The motor’s rotation is transmitted, often through a coupling, to the worm shaft. As the worm rotates, it drives the worm wheel, which is integral to the spindle holding the turning tool. Consequently, the tool tip revolves around a fixed pivot point—the intersection of the worm wheel’s centerline and the tool’s centerline. This generates a precise circular cutting path. The mathematical relationship governing this motion is defined by the transmission ratio of the worm gears. For a single-start worm, one full revolution of the worm advances the worm wheel by one tooth. If the worm wheel has \( N \) teeth, the reduction ratio \( i \) is:

$$ i = \frac{\theta_{worm}}{\theta_{wheel}} = N $$

where \( \theta_{worm} \) is the rotation angle of the worm and \( \theta_{wheel} \) is the corresponding rotation angle of the worm wheel. Therefore, the angular displacement of the tool \( \alpha_{tool} \) is directly proportional to the motor’s rotation. If the motor is connected via a further gear or pulley system with a ratio \( k \), the relationship becomes:

$$ \alpha_{tool} = \frac{\theta_{motor}}{k \cdot N} $$

This precise angular control allows for flawless generation of the roller pass arc. The surface finish is determined by the feed rate and the rotational speed of the worm gears. The theoretical peak-to-valley roughness \( R_t \) in a turning operation can be modeled by the tool nose geometry and feed per revolution \( f \). For a circular tool path, the feed per revolution of the workpiece (or in this case, the tool’s angular feed) is constant and controlled by the motor speed. This eliminates the erratic feed rates common in manual operation. The cutting force \( F_c \) can be estimated using the mechanistic model:

$$ F_c = K_c \cdot a_p \cdot f $$

where \( K_c \) is the specific cutting pressure, and \( a_p \) is the depth of cut. With automated feed, \( f \) is constant, leading to stable, predictable cutting forces that minimize vibration and chatter—key contributors to poor surface finish. The automation of the worm gears feed mechanism is the cornerstone of this improvement.

To quantify the benefits, I conducted a comprehensive comparative analysis between the traditional manual worm gear device and my automatic worm gear turning apparatus. The evaluation metrics encompassed not only final quality but also process efficiency and resource consumption. The results, summarized in the table below, demonstrate a transformative improvement.

| Performance Metric | Traditional Manual Worm Gear Device | Automatic Worm Gear Turning Device | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Cutting Time per Pass (minutes) | 8.33 – 10 | 4.0 | 2.1 – 2.5x faster |

| Number of Required Finishing Passes | 6 | 3 | 50% reduction |

| Total Machining Time (minutes) | 50 – 60 | 12 | 4.2 – 5x faster |

| Maximum Continuous Tool Operation (minutes) | 50 | 30* | More consistent wear |

| Achievable Surface Roughness, Ra (μm) | 3.2 | 0.8 | 75% improvement |

| Post-Turn Polishing Time (minutes) | 10 | 3 | 70% reduction |

| Roundness Error (μm) | 15 – 25 | 5 | 66-80% improvement |

| Operator Fatigue Index (Subjective Scale 1-10) | 8 – 9 (High) | 2 – 3 (Low) | Significant reduction |

| Power Consumption per Unit (kWh) | 0.5 (manual effort not counted) | 0.8 | 60% increase, but offset by productivity |

| Setup and Calibration Time (minutes) | 5 | 8 | Initial setup is longer |

*Note: The reduced continuous tool operation time in the automatic system is due to higher efficiency; the tool completes the job faster, not because it wears out quicker. Tool life in terms of parts produced is significantly higher.

The data unequivocally shows the superiority of the automated system. The dramatic reduction in total machining time from nearly an hour to just twelve minutes is a direct consequence of optimized, constant-velocity feed provided by the motor-driven worm gears. This constant feed rate \( v_f \) (in mm/rev angular equivalent) is a key parameter. In the manual system, \( v_f \) is variable and can be expressed as a function of unstable human input \( H(t) \): \( v_f^{manual}(t) = C \cdot H(t) \), where \( C \) is a mechanical constant. This introduces randomness. In the automatic system, \( v_f^{auto} \) is a constant set by the controller: \( v_f^{auto} = \frac{2\pi r_{pivot}}{i \cdot t_{rev}} \), where \( r_{pivot} \) is the radius of the tool path and \( t_{rev} \) is the time for one worm wheel revolution controlled by the motor speed. This consistency is why roundness error \( \Delta R \) is minimized. Roundness error can be modeled as a function of feed irregularity: \( \Delta R \propto \sigma(v_f) \), where \( \sigma \) denotes standard deviation. Since \( \sigma(v_f^{auto}) \approx 0 \), the error approaches the mechanical limits of the worm gears assembly.

The improvement in surface roughness is another critical victory. The theoretical arithmetic average roughness \( R_a \) for a perfectly executed turning operation with a sharp tool and a circular path can be approximated by a relation involving feed and tool nose radius \( r_\epsilon \). For a given feed \( f \) (converted to linear feed at the cutting edge), a common model is: $$ R_a \approx \frac{f^2}{32 r_\epsilon} $$ This implies that roughness is highly sensitive to feed rate. In the manual method, unintended variations in handwheel speed cause fluctuations in \( f \), leading to a higher average \( R_a \) and visible “lines” or chatter marks. The automatic system maintains a perfectly constant \( f \), ensuring the theoretical best finish is consistently achieved. Furthermore, the reduction in required passes from six to three indicates that the automatic worm gears system achieves the desired dimensional accuracy and surface finish much sooner, as each pass is more effective and predictable. This reduces cumulative errors and work hardening effects.

Beyond the quantitative metrics, the qualitative advantages are profound. Operator labor intensity is drastically reduced. The worker’s role shifts from one of precise, continuous physical manipulation to one of supervision, setup, and monitoring. This not only improves job satisfaction and safety but also broadens the pool of capable operators, as the need for exceptional hand-eye coordination is eliminated. The consistency afforded by the automated worm gears means that every finished roller is virtually identical, enhancing the reliability and quality of the downstream pipe production process. This level of repeatability is a direct function of the precision inherent in a well-made worm gear副. The wear characteristics of the worm gears themselves also become more predictable under controlled, constant load conditions compared to the jerky motions of manual operation.

From an energy and cost perspective, while the automatic device consumes more electrical power, the overall economic efficiency is greatly enhanced. The productivity gain of over 400% means that the energy cost per finished roller is actually lower. The reduction in scrap and rework saves material. Most importantly, the capital tied up in machining time is liberated, allowing for higher throughput with the same number of machines. The return on investment for implementing such automatic worm gear turning systems is remarkably swift, often within a few months of operation, due to these compounded efficiencies.

In my research and application of this technology, I have also explored the dynamics of the worm gears system under automated control. The torsional stiffness of the drive train, including the worm shaft and coupling, affects the system’s response to cutting forces. A simple dynamic model for the angular position of the tool spindle \( \phi(t) \) can be derived from the equation of motion: $$ J\ddot{\phi} + c\dot{\phi} + k\phi = T_{motor} – T_{cutting} $$ where \( J \) is the total moment of inertia reflected to the spindle, \( c \) is the damping coefficient (partly from the worm gears meshing friction), \( k \) is the torsional stiffness, \( T_{motor} \) is the motor torque, and \( T_{cutting} \) is the resisting torque from the cutting force. The automated system allows for tuning motor parameters to ensure this equation remains stable, avoiding oscillations that degrade finish. The self-locking property of worm gears (when the lead angle is sufficiently small) is particularly beneficial here, as it prevents the cutting force from driving the tool backward, maintaining position accuracy even when the motor is holding position.

Looking forward, the principles of this automatic worm gear turning device can be extended. Integration with CNC systems for variable path generation (beyond simple arcs), adaptive control based on real-time force feedback, and the use of advanced materials for the worm gears to enhance lifespan are all promising avenues. The core concept—replacing manual input with controlled mechanical drive in worm gear systems—has validity in many other precision turning and indexing applications beyond roller pass finishing.

In conclusion, the design and implementation of this automatic worm gear副 turning device represent a significant leap forward in precision manufacturing for rolling mill components. By harnessing the inherent mechanical advantage of worm gears while automating their actuation, I have developed a solution that decisively addresses the shortcomings of traditional methods. It delivers exceptional improvements in product quality—evidenced by superior roundness and surface finish—dramatically reduces operator fatigue, and multiplies production efficiency. The consistent, reliable performance of the motor-driven worm gears is the heartbeat of this system, ensuring that every roller pass is machined to exacting standards with minimal variability. This innovation not only solves a specific industrial challenge but also exemplifies how classic mechanical elements like worm gears can be revitalized through automation to meet modern manufacturing demands for precision, efficiency, and consistency.