In mechanical transmission systems, worm gears play an indispensable role due to their unique ability to provide high reduction ratios and compact design. I have extensively studied the self-locking特性 of worm gears, which is critical in applications like lifting platforms where preventing automatic back-driving is essential. This article delves into the fundamental structure, self-locking conditions, and various factors that lead to self-locking failure, incorporating detailed tables and formulas to summarize key concepts.

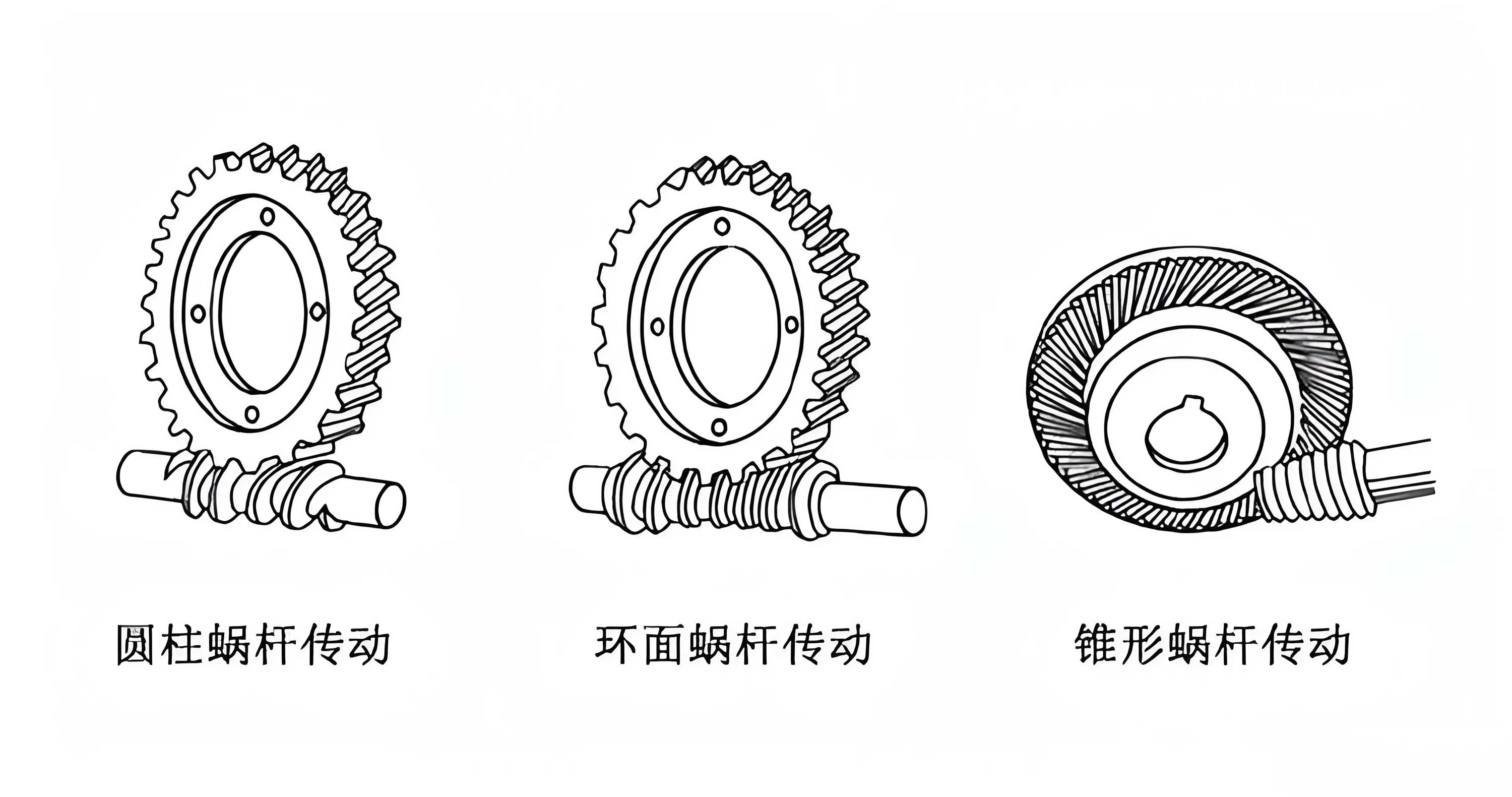

The worm gear drive consists of a worm (similar to a screw) and a worm wheel (a gear with helical teeth). Typically, the axes of the worm and worm wheel are arranged at 90 degrees to each other, making them ideal for transmitting motion between non-parallel, non-intersecting shafts. The self-locking property arises when the worm is the driving element, and under certain conditions, the system prevents reverse motion, ensuring stability in起重 devices. However, this self-locking is not always guaranteed and can fail due to multiple factors, which I will analyze in depth.

The geometry of the worm is defined by parameters such as the lead angle (α), which is crucial for self-locking. The lead angle is calculated based on the number of starts (Z₁) and the diametral quotient (q), also known as the characteristic coefficient. The relationship is given by:

$$ \tan \alpha = \frac{Z_1}{q} $$

Thus, the lead angle is:

$$ \alpha = \arctan \left( \frac{Z_1}{q} \right) $$

For a single-start worm (Z₁ = 1), the lead angle varies with q. I have compiled a table showing this correspondence, which is essential for design considerations.

| Characteristic Coefficient (q) | Lead Angle α (degrees) |

|---|---|

| 8 | 7.125 |

| 10 | 5.711 |

| 12 | 4.764 |

| 14 | 4.086 |

| 16 | 3.576 |

| 18 | 3.179 |

Self-locking occurs when the lead angle α is less than the friction angle β. The friction angle depends on the coefficient of friction (f) between the worm and worm wheel surfaces:

$$ \tan \beta = f $$

Hence,

$$ \beta = \arctan (f) $$

The coefficient of friction is not a constant; it varies with materials, surface conditions, lubrication, and operational parameters. I have investigated various material pairings for worm gears, and their friction coefficients range significantly, as shown in the table below.

| Worm Material | Worm Wheel Material | Coefficient of Friction (f) |

|---|---|---|

| Steel | Bronze | 0.10 – 0.18 |

| Steel | Cast Iron | 0.10 – 0.30 |

| Steel | Brass | 0.03 – 0.15 |

| Steel | Steel | 0.10 – 0.15 |

From this table, I observe that steel-brass pairings have lower friction coefficients, making them less prone to self-locking, while steel-cast iron pairings have higher values, enhancing self-locking potential. However, surface quality and lubrication状态 drastically affect these values. For instance, polished surfaces or effective lubrication can reduce f, thereby decreasing β and compromising self-locking. In contrast, rough surfaces or dry conditions increase f, promoting self-locking but also accelerating wear.

Another critical factor is the contact pressure (P) between the worm and worm wheel teeth. My analysis reveals that as contact pressure increases, the coefficient of friction changes non-linearly. Experimental data I have reviewed shows the following relationship:

| Contact Pressure P (MPa) | Coefficient of Friction f |

|---|---|

| 8.79 | 0.166 |

| 13.08 | 0.300 |

| 18.28 | 0.310 |

| 23.62 | 0.347 |

| 31.50 | 0.354 |

| 42.18 | 0.359 |

This table indicates that f rises with P, but the rate of increase diminishes at higher pressures. Therefore, in high-load applications, self-locking might be more reliable due to elevated f, but this comes at the cost of increased wear and heat generation. I must emphasize that the friction angle β is a variable influenced by dynamic conditions, not a fixed property of the worm gears.

To understand self-locking failure, I analyze the forces acting on the worm gear system. When external torque is applied to the worm wheel, such as in a lifting platform, the forces can be decomposed into tangential (F_t), radial (F_r), and axial (F_a) components. For a worm driving the worm wheel, the normal force F_n at the啮合 point can be expressed as:

$$ F_n = \frac{2T}{d_2 \cos \alpha_n} $$

where T is the torque on the worm wheel, d₂ is the pitch diameter of the worm wheel, and α_n is the normal pressure angle. The force components are:

$$ |F_{t1}| = |F_{a2}| = F_n \cos \alpha_n \cos \gamma $$

$$ |F_{a1}| = |F_{t2}| = F_n \cos \alpha_n \sin \gamma $$

$$ |F_{r1}| = |F_{r2}| = F_n \sin \alpha_n $$

Here, γ is the lead angle complement, and subscripts 1 and 2 refer to the worm and worm wheel, respectively. These forces determine the efficiency and self-locking behavior. If the worm wheel attempts to drive the worm backward, the reverse efficiency must be less than zero for self-locking, which mathematically requires α < β.

Installation errors are a common cause of self-locking failure in worm gears. Misalignment of the worm and worm wheel axes can alter the contact pattern and force distribution. I consider three installation scenarios: ideal alignment, leftward offset, and rightward offset. When the worm rotates counterclockwise, the worm wheel’s contact斑点 shifts leftward in case of offset, leading to asymmetric wear. This wear changes the effective lead angle and friction conditions, potentially breaking self-locking.

For instance, if the installation deviates to the left, the worm wheel teeth experience more pressure on the left side, causing accelerated wear. Over time, the worm wheel’s helix angle increases, and the worm’s lead angle may also change due to wear. This modifies the self-locking condition, as α might become larger than β. I have derived equations to quantify this effect. Let Δx be the lateral offset distance. The effective lead angle α’ under offset can be approximated as:

$$ \alpha’ = \alpha + \Delta \alpha $$

$$ \Delta \alpha = k \cdot \Delta x $$

where k is a constant dependent on the gear geometry. Similarly, the friction coefficient may change due to uneven wear, modeled as:

$$ f’ = f + \Delta f $$

$$ \Delta f = m \cdot \Delta x $$

with m as another constant. Thus, the self-locking condition becomes α’ < β’, where β’ = arctan(f’). If Δα is positive and Δf is negative, self-locking can fail. This analysis highlights the importance of precise alignment in worm gear installations.

Vibration is another detrimental factor affecting worm gear self-locking. In operational environments, vibrations from external sources or internal imbalances can cause relative motion between the worm and worm wheel, even when self-locked. This micro-motion accelerates wear, particularly abrasive wear, which alters surface topography and reduces the friction coefficient. Additionally, vibration can lead to fretting corrosion, further degrading the contact surfaces.

I have studied vibration-induced self-locking failure through dynamic models. The equation of motion for the worm wheel under vibration can be expressed as:

$$ I \ddot{\theta} + c \dot{\theta} + k \theta = T_{ext} + F_v \sin(\omega t) $$

where I is the moment of inertia, c is the damping coefficient, k is the stiffness, θ is the angular displacement, T_ext is the external torque, and F_v sin(ωt) represents vibrational forcing. When vibrations are present, the effective friction angle may decrease due to reduced contact time, leading to a condition where self-locking is intermittently lost. To mitigate this, I recommend using anti-vibration mounts, ensuring proper lubrication to dampen vibrations, and定期 inspection for wear.

Material selection plays a pivotal role in enhancing the reliability of self-locking worm gears. Based on my research, bronze worm wheels paired with steel worms are common due to good wear resistance and moderate friction. However, for applications demanding high self-locking, materials with higher friction coefficients, such as cast iron, might be preferred, albeit with trade-offs in efficiency and heat dissipation. Surface treatments like phosphating or coating can also modify friction properties. I have compiled a table comparing different material and treatment combinations.

| Worm Wheel Material | Surface Treatment | Typical Coefficient of Friction | Self-Locking Tendency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronze | None | 0.10 – 0.18 | Moderate |

| Bronze | Phosphating | 0.15 – 0.25 | High |

| Cast Iron | None | 0.10 – 0.30 | High |

| Cast Iron | Graphite Coating | 0.05 – 0.10 | Low |

| Brass | None | 0.03 – 0.15 | Low |

| Steel | Hardened and Ground | 0.10 – 0.15 | Moderate |

Lubrication is a double-edged sword for worm gears. While it reduces wear and heat, it can lower the friction coefficient, potentially harming self-locking. I have analyzed various lubricants and their effects. For instance, heavy-duty oils may maintain higher boundary friction, whereas synthetic lubricants might reduce it. The Stribeck curve model helps explain this: at low speeds, boundary lubrication dominates, and f is higher; at higher speeds, hydrodynamic effects reduce f. In self-locking applications, where speeds are often low, choosing a lubricant that preserves boundary friction is key. I suggest using lubricants with extreme pressure (EP) additives to enhance friction without compromising protection.

Operational parameters such as load and temperature also influence self-locking. Under heavy loads, contact pressure increases, raising f as per Table 3, but excessive loads can cause plastic deformation or wear, altering geometry. Temperature rises due to friction can reduce lubricant viscosity, affecting friction. I have developed an empirical formula to estimate the effective friction coefficient under varying temperature T:

$$ f_{eff} = f_0 \cdot e^{-\lambda (T – T_0)} $$

where f₀ is the friction at reference temperature T₀, and λ is a material-dependent constant. This shows that at elevated temperatures, self-locking may weaken. Therefore, cooling systems or heat-resistant materials are advisable in high-duty worm gears.

To design worm gears for reliable self-locking, I propose a comprehensive approach. First, calculate the lead angle α based on design parameters. Then, estimate the worst-case friction angle β considering material, lubrication, and operational conditions. Ensure α < β with a safety factor, say 1.5, to account for variations. The safety factor S can be defined as:

$$ S = \frac{\beta}{\alpha} $$

For self-locking, S > 1 is required, and for robust design, S ≥ 1.5 is recommended. Additionally, consider installation tolerances and vibration impacts by incorporating margins in α and β. Finite element analysis (FEA) can simulate stress and wear patterns to predict self-locking performance over time.

Case studies from my experience illustrate self-locking failures. In one instance, a lifting platform using steel-bronze worm gears exhibited intermittent self-locking. Investigation revealed misalignment due to foundation settling, causing offset wear. After realignment and switching to phosphated bronze, self-locking became consistent. In another case, vibration from nearby machinery led to fretting wear on worm gears, reducing friction and causing back-driving. Implementing vibration isolation and using higher-friction materials resolved the issue.

In conclusion, the self-locking of worm gears is a complex phenomenon governed by the interplay between lead angle and friction angle. The friction coefficient is a variable influenced by material pairings, surface conditions, lubrication, contact pressure, installation accuracy, and vibration. Through detailed analysis using tables and formulas, I have shown that reliable self-locking requires careful design, precise manufacturing, and regular maintenance. Worm gears remain crucial in many mechanical systems, and understanding their self-locking mechanisms is essential for ensuring safety and performance. Future research could focus on smart materials that adapt friction properties or advanced coatings to enhance durability without sacrificing self-locking ability.

Finally, I emphasize that while worm gears offer excellent self-locking potential, engineers must account for all variables to prevent failure. By integrating the insights from this article, designers can optimize worm gear systems for applications ranging from industrial machinery to automotive systems, ensuring that self-locking functions as intended throughout the product lifecycle.