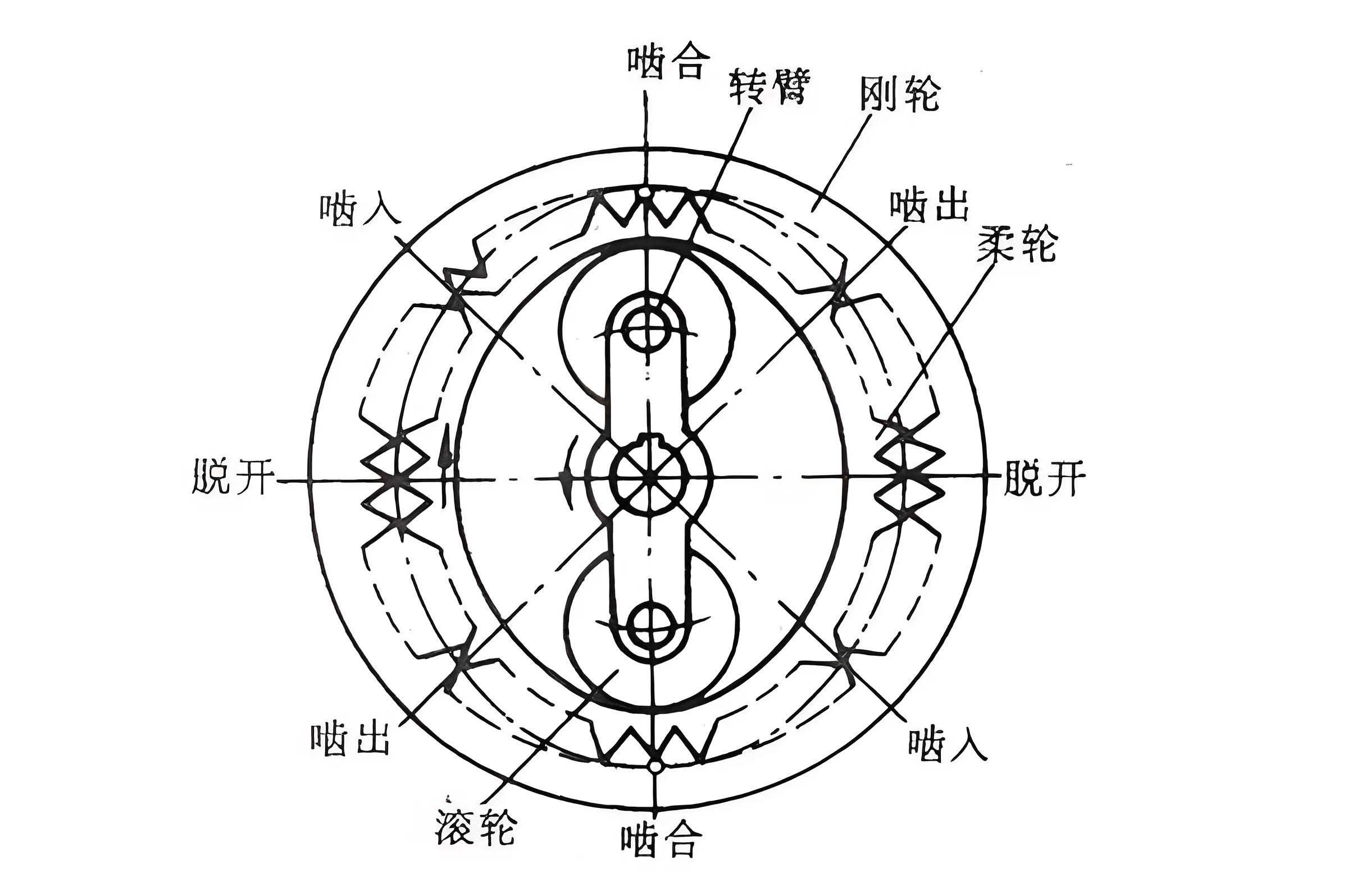

In the realm of precision motion control and robotics, the strain wave gear, often referred to as harmonic drive, stands out as a pivotal technology due to its exceptional characteristics: high reduction ratios, compactness, minimal backlash, and substantial torque capacity. My focus in this exploration is on a critical component within this system—the wave generator. Specifically, I delve into the design and analysis of a double disk wave generator, a configuration known for its structural simplicity and robust load-bearing capabilities. However, a inherent challenge arises because the two disks are axially offset on different planes, leading to asymmetrical deformation and stress distribution in the flexible spline, or flexspline, during operation. This asymmetry can compromise transmission accuracy and longevity. Therefore, I propose an enhanced design methodology where the parameters of the front and rear disks are independently calculated based on a straight generatrix assumption, aiming to achieve uniform radial deformation at a designated cross-section of the flexspline. This article meticulously details this design approach, presents a comparative finite element analysis using a real-world case study, and evaluates the resulting improvements in deformation characteristics and stress profiles. Throughout this discussion, the term ‘strain wave gear’ will be frequently emphasized to underscore its central role in advanced mechanical transmissions.

The fundamental operation of a strain wave gear relies on the elastic deformation of a thin-walled flexspline by a wave generator, typically comprising an elliptical cam or a set of disks, which meshes with a rigid circular spline. The double disk wave generator consists of two circular disks mounted on a common shaft but separated axially. When inserted into the flexspline, these disks force it into a non-circular shape, creating two major axes of engagement. The primary issue, as observed in conventional designs, is that the axial separation leads to different effective cone angles ($\alpha_1$ and $\alpha_2$) at the contact zones of the front and rear disks. This discrepancy causes non-uniform radial and circumferential displacements along the flexspline’s length, particularly noticeable in cup-type flexsplines. My objective is to mitigate this by tailoring each disk’s geometry—calculation radius and eccentricity—so that the radial deformation at a specific reference cross-section, often the midsection of the gear rim, matches a predetermined value. This approach ensures that both contact regions induce nearly identical deformation patterns, promoting smoother operation and enhanced performance of the strain wave gear.

To establish the theoretical foundation, I begin with the kinematics of flexspline deformation. Under the assumption that the flexspline’s generatrix remains straight during deformation—a common simplification for thin-walled shells—the neutral surface of the undeformed flexspline is a cylinder of radius $r_m$. Upon assembly with the wave generator, it adopts a shape described by a variable radial displacement $w(\phi)$, where $\phi$ is the angular coordinate measured from the major axis. The resultant radial coordinate $\rho(\phi)$ is:

$$ \rho(\phi) = r_m + w(\phi) $$

For a disk-type wave generator, the contact region between the disk and the flexspline spans a wrap angle $\gamma$. Within this arc, the flexspline conforms to the circular profile of the disk. The radial displacement $w(\phi)$ within the contact zone ($-\gamma/2 \leq \phi \leq \gamma/2$) can be derived from geometric compatibility. The key design parameters for a disk are its calculation radius $R$ and the eccentricity $e$, which is the offset between the disk’s center and the wave generator’s central axis. Given the desired maximum radial deformation $w_0$ at the major axis ($\phi=0$), and the neutral radius $r_m$, the disk calculation radius $R$ for a specified wrap angle $\gamma$ is expressed as:

$$ R = \frac{r_m^2 – A B}{w_0 B + r_m (A – B)} $$

where $A$ and $B$ are geometric constants defined by:

$$ A = \frac{\pi}{2} – \gamma – \sin \gamma \cos \gamma $$

$$ B = \frac{4}{\pi} \left[ \cos \gamma – \left(\frac{\pi}{2} – \gamma\right) \sin \gamma \right] $$

The corresponding eccentricity $e$ is then:

$$ e = r_m + w_0 – R $$

In a conventional double disk wave generator, both disks share identical parameters $R$ and $e$. However, due to the axial offset, the effective radial deformation induced by the rear disk at the reference cross-section differs from that of the front disk. To address this, I independently compute parameters for the rear disk. Let $l_1$ denote the distance from the reference cross-section (typically the gear midplane) to the rear disk’s contact center, and $\delta$ be the width of the flange or rim section. The effective radial deformation $w_0’$ that the rear disk must produce at the reference cross-section, considering the straight generatrix, is:

$$ w_0′ = \frac{(l_1 – b_c – \delta) w_0}{l_1} $$

Here, $b_c$ represents the effective contact width between the disk and the flexspline inner wall. Empirical studies suggest $b_c \approx 0.1 R$ for practical designs. Using this adjusted deformation $w_0’$, I calculate the rear disk’s radius $R_2$ and eccentricity $e_2$ using the same formulas above, but substituting $w_0’$ for $w_0$. Consequently, the rear disk will have a larger calculation radius and smaller eccentricity compared to the front disk, compensating for the axial offset and ensuring consistent deformation at the reference plane.

To validate this design methodology, I employ a detailed case study based on the commercial CSF-90 strain wave gear component. The key geometric parameters of the cup-type flexspline are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Neutral layer radius | $r_m$ | 120.99 mm |

| Cup length | $l$ | 112.5 mm |

| Shell thickness | $h_1$ | 2.69 mm |

| Gear rim width | $b$ | 47 mm |

| Number of teeth | $z$ | 200 |

| Rim thickness | $h_2$ | 2.99 mm |

| Cup bottom inner diameter | $d_2$ | 110 mm |

| Maximum radial deformation | $w_0$ | 1.25 mm |

| Flange width | $\delta$ | 3.5 mm |

| Disk wrap angle | $\gamma$ | 30° |

For the conventional design (before improvement), both disks have identical parameters. Applying the formulas with $\gamma = 30^\circ$, $r_m = 120.99$ mm, and $w_0 = 1.25$ mm, I compute:

$$ R_1 = R_2 = 118.006 \text{ mm}, \quad e_1 = e_2 = 4.23 \text{ mm} $$

The contact width is taken as $b_c = 0.1 R_1 \approx 11.8$ mm. For the improved design, I first determine the rear disk’s target deformation. Assuming the reference cross-section is at the mid-length of the gear rim, $l_1$ is approximately half the cup length minus some offset; for simplicity, let $l_1 = 50$ mm (a representative value from the geometry). Then:

$$ w_0′ = \frac{(50 – 11.8 – 3.5) \times 1.25}{50} \approx 0.87 \text{ mm} $$

Using $w_0′ = 0.87$ mm in the disk radius formula yields:

$$ R_2 = 118.50 \text{ mm}, \quad e_2 = 3.51 \text{ mm} $$

The front disk parameters remain unchanged: $R_1 = 118.006$ mm, $e_1 = 4.23$ mm. This independent parameter set constitutes the improved double disk wave generator for the strain wave gear.

Next, I construct a parametric finite element model to simulate the assembly and contact between the flexspline and the wave generator. The modeling is performed using ANSYS Parametric Design Language (APDL) to ensure flexibility and accuracy. The flexspline is discretized using SHELL63 elements for the cup shell, which capture both membrane and bending effects. The gear teeth are modeled as a series of beam elements (BEAM44) attached to the shell rim, with real constants defined to approximate the inertial properties of the actual tooth profile. This simplification significantly reduces computational cost while maintaining fidelity for stress and deformation analysis in the cup body. The wave generator disks are treated as rigid surfaces since the flexibility of the bearing is neglected in this study; they are meshed with TARGE174 elements. The inner surface of the flexspline is defined as a deformable contact surface using CONTA174 elements, establishing a surface-to-surface contact pair with the rigid disks. Boundary conditions are applied by fully constraining all degrees of freedom at the nodes on the cup bottom inner diameter and the wave generator shaft surfaces, simulating a fixed support condition. The finite element assembly model accurately represents the physical interaction within the strain wave gear.

The finite element analysis solves for the deformation and stress states under assembly preload. To evaluate the performance, I extract results along defined paths on the flexspline’s neutral surface at the gear rim midsection, corresponding to the regions influenced by the front and rear disks. The primary metrics are radial displacement $w$, circumferential displacement $v$, von Mises equivalent stress, and circumferential stress $\sigma_\theta$. A comparative study between the conventional and improved wave generator designs is conducted.

First, consider the radial displacement profiles. Figure 1 illustrates the radial displacement as a function of angular position $\phi$ (where $\phi=0^\circ$ is the major axis) for both designs. For the conventional design, the curves for the front and rear disk zones show significant deviation, especially near the major axis. At $\phi=0^\circ$, the difference reaches approximately 0.236 mm, which is about 19% of the maximum radial deformation. This inconsistency indicates non-uniform expansion of the flexspline, which could lead to uneven load distribution across the teeth of the strain wave gear. In contrast, for the improved design, the radial displacement curves for the front and rear zones are virtually superimposed over the entire contact arc. The maximum difference is reduced to merely 1.2% of $w_0$, demonstrating excellent conformity. The quantitative comparison of radial displacement differences ($\Delta w = w_{\text{front}} – w_{\text{rear}}$) is summarized in Table 2.

| Angular Position $\phi$ (°) | Conventional Design $\Delta w$ (mm) | Improved Design $\Delta w$ (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | -0.236 | -0.015 |

| 15 | -0.118 | -0.008 |

| 30 | -0.045 | -0.003 |

| 45 | 0.012 | 0.001 |

| 60 | 0.052 | 0.004 |

| 75 | 0.075 | 0.005 |

| 90 | 0.082 | 0.006 |

The circumferential displacement behavior is equally important as it relates to the torsional stiffness and meshing kinematics of the strain wave gear. For the conventional design, the circumferential displacements in the rear disk zone are consistently larger in magnitude than those in the front zone, and even exhibit a sign reversal (negative values) near the wrap angle boundary, indicating complex shear deformation. This asymmetry can induce undesired cross-sectional distortions. With the improved wave generator, the circumferential displacement curves for both zones align closely, with nearly identical values across all angles. This uniformity suggests that the flexspline deforms more like a pure bending mode, which is ideal for smooth engagement in the strain wave gear system.

Stress analysis reveals critical insights into the structural integrity and fatigue life of the strain wave gear. The von Mises equivalent stress distributions along the flexspline cup, from the major axis ($\phi=0^\circ$) to the minor axis ($\phi=90^\circ$) and beyond into the second quadrant, are plotted for both designs. The improved design consistently shows lower stress levels, particularly in the region dominated by the rear disk ($\phi$ between 90° and 180°). For instance, at $\phi=150^\circ$, the equivalent stress decreases from 102.11 MPa to 87.16 MPa, a reduction of 14.6%. This reduction is attributed to the more uniform deformation, which alleviates stress concentrations. Similarly, the circumferential stress $\sigma_\theta$, which is crucial for assessing hoop stresses in the thin wall, shows significant improvement. In the compressive stress region ($\phi$ from 90° to 135°), the maximum compressive stress drops from -88.50 MPa to -80.11 MPa (9.5% reduction). In the tensile stress region ($\phi$ from 135° to 180°), the peak tensile stress falls from 89.39 MPa to 73.82 MPa, a substantial 17.4% decrease. These stress reductions are quantitatively compared in Table 3.

| Angular Position $\phi$ (°) | Stress Type | Conventional Design (MPa) | Improved Design (MPa) | Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150 | Von Mises Equivalent | 102.11 | 87.16 | 14.6 |

| 120 | Circumferential (Compressive) | -88.50 | -80.11 | 9.5 |

| 160 | Circumferential (Tensile) | 89.39 | 73.82 | 17.4 |

The underlying reason for these improvements lies in the kinematic compatibility enforced by the independent disk design. By tailoring the rear disk’s geometry to produce the desired radial deformation at the reference cross-section, the effective cone angles $\alpha_1$ and $\alpha_2$ become nearly equal. This minimizes the differential stretching and bending along the flexspline’s length, leading to a more symmetric deformation field. Consequently, the load path through the strain wave gear becomes more uniform, reducing peak stresses and potential fatigue hotspots. It is worth noting that while the straight generatrix assumption simplifies the analysis, the finite element results confirm its adequacy for engineering design purposes in this context.

In conclusion, this study presents a refined design methodology for double disk wave generators in strain wave gear systems. By independently calculating the front and rear disk parameters based on a specified radial deformation at a critical cross-section, the inherent deformation asymmetry due to axial offset can be effectively mitigated. The finite element simulation, grounded in a realistic case study, demonstrates that the improved design yields highly consistent radial and circumferential displacements between the two disk engagement zones. Moreover, significant reductions in equivalent and circumferential stresses are achieved, particularly in the rear disk region, which enhances the overall durability and performance of the strain wave gear. This approach offers a practical advancement for designers aiming to optimize wave generator configurations for high-precision, high-load applications such as robotic joints, aerospace actuators, and precision machinery. Future work could explore dynamic analyses under load, the influence of tooth engagement on stress, and experimental validation to further solidify the benefits of this tailored design for strain wave gears.