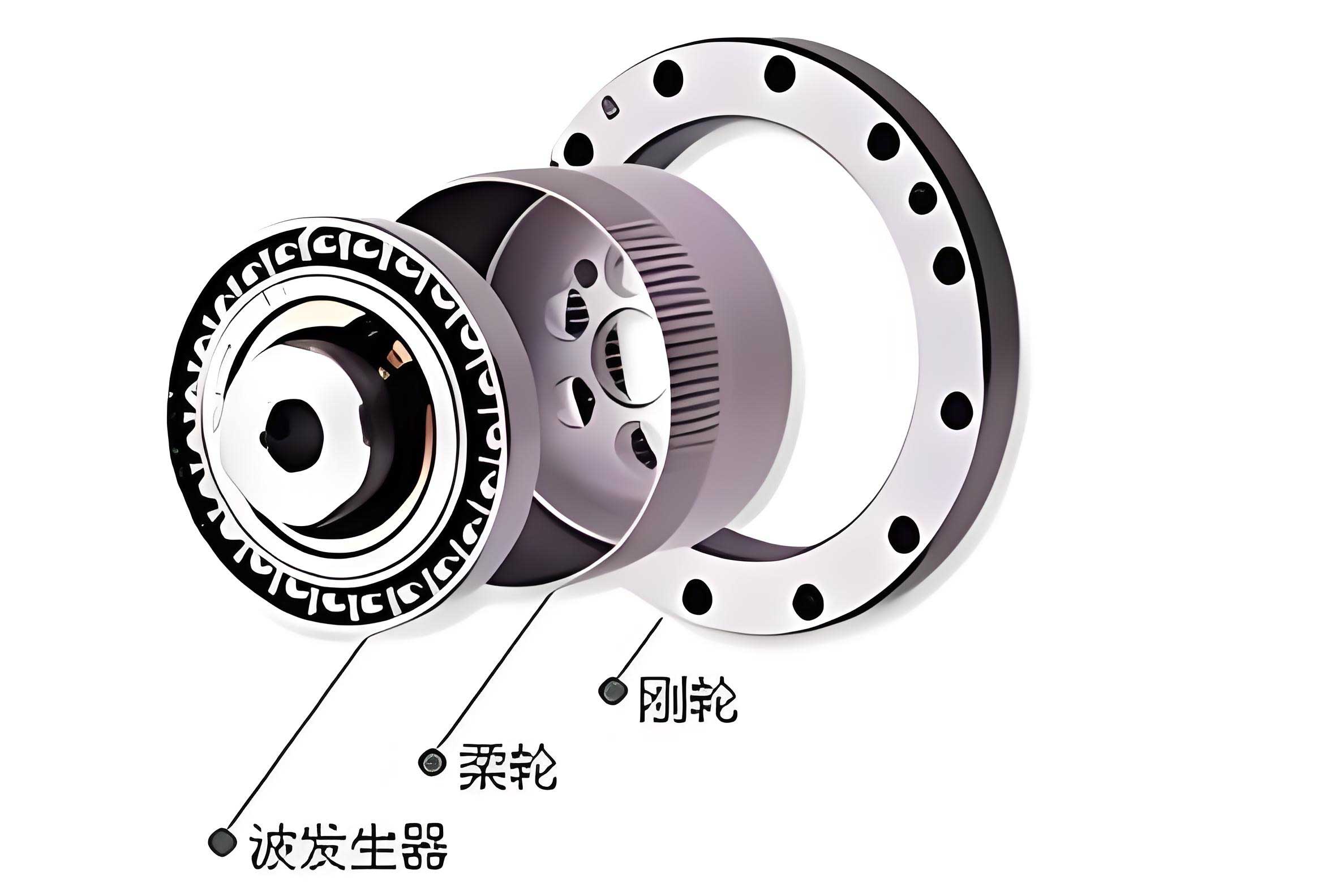

In the field of precision motion control and robotics, the demand for compact, high-ratio, and backlash-free transmission systems is ever-present. Among the various solutions, the strain wave gear, also commonly referred to as a harmonic drive, stands out due to its unique operating principle and exceptional performance characteristics. This mechanism achieves speed reduction and torque multiplication through the elastic deformation of a flexible spline, or “flexspline,” by an elliptical wave generator. The subsequent meshing with a rigid circular spline creates a high reduction ratio in a remarkably small package. The advantages of the strain wave gear are numerous, including high torque density, exceptional positional accuracy and repeatability, near-zero backlash, and coaxial input/output shafts. These properties make the strain wave gear indispensable in applications ranging from aerospace actuators and robotic joints to precision medical equipment and optical positioning systems.

Despite their widespread use, the design and analysis of strain wave gears present significant challenges, primarily due to the complex non-linear interactions between components. The process involves large deformations of the flexspline, evolving contact conditions between multiple surfaces, and material non-linearity. Traditional analytical methods often rely on simplifying assumptions that may not capture the true dynamic behavior or stress state within the gear, particularly under high loads or during transient conditions like startup and reversal. Therefore, advanced numerical simulation techniques have become essential tools for gaining deeper insights, optimizing designs, and predicting performance and fatigue life.

This article details a comprehensive methodology for simulating the complete operational cycle of a strain wave gear, from initial assembly to dynamic meshing under rotation, using the explicit dynamics solver LS-DYNA within the ANSYS software environment. We propose and validate a novel pre-processing and assembly simulation technique designed to overcome a critical hurdle in explicit dynamic analysis of strain wave gears: the initial geometric interference, or “penetration,” between components in their nominal CAD assembly state. Following the successful virtual assembly, we apply rotational motion to the wave generator to simulate the dynamic engagement of the strain wave gear, extracting detailed results on kinematic trajectories and stress distributions.

Challenges in Explicit Dynamic Simulation of Strain Wave Gears

The primary obstacle when attempting a dynamic simulation of a pre-assembled strain wave gear model in an explicit code like LS-DYNA is the definition of the initial state. In a standard CAD model, the components of a strain wave gear—the wave generator, flexspline, and circular spline—are typically positioned in their theoretical working configuration. This implies that the major axis of the elliptical wave generator is already inserted into and deforming the flexspline, and the teeth of the flexspline are partially engaged with those of the circular spline. From a finite element perspective, this results in initial nodal penetration between the contacting surfaces.

Explicit solvers, which integrate equations of motion using a central difference scheme conditional on a very small time step, are highly sensitive to such initial conditions. Severe initial penetrations can lead to immense, non-physical contact forces at the very first time step, causing numerical instability and simulation failure. Therefore, a simulation strategy must address this issue by defining a geometrically compatible, penetration-free starting configuration from which the physical assembly and operational process can be dynamically simulated.

Proposed Methodology for Simulated Assembly

Our proposed solution involves a two-stage approach conducted entirely within the simulation environment: first, a simulated assembly process to bring the components from a separated, non-interfering state into their working configuration, followed by the dynamic meshing simulation. The key innovation lies in the pre-processing of the wave generator geometry to facilitate this assembly.

We begin with three independent, unmeshed CAD models: the flexspline, the circular spline, and a simplified wave generator. A critical simplification, common in strain wave gear analysis, is to model the wave generator and its compliant bearing as a single, rigid elliptical body. This is justified as the primary interest often lies in the response of the flexspline. The nominal dimensions are derived from a commercial strain wave gear unit, with key parameters summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Description | Value (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| $Z_r$ | Number of teeth on Flexspline | 160 |

| $Z_g$ | Number of teeth on Circular Spline | 162 |

| $\mu$ | Gear Reduction Ratio ($\mu = \frac{Z_g}{Z_g – Z_r}$) | 80 |

| $d_w$ | Inner diameter of Flexspline barrel | 49.05 |

| $d_a$ | Major axis diameter of Wave Generator | 49.758 |

| $d_b$ | Minor axis diameter of Wave Generator | 48.302 |

| $L_3$ | Initial axial separation, WG to FS | 10.0 |

| $L_4$ | Initial axial separation, CS to FS | 20.0 |

The standard assembly issue is that $d_a > d_w$, meaning the wave generator cannot be axially inserted into the flexspline without causing interference. To solve this, we modify the wave generator geometry by adding a short, tapered section (a “draft”) at both of its axial ends. The geometry of this draft is calculated to provide a smooth transition for the flexspline’s inner surface to ride onto the wave generator’s major axis during the simulated axial insertion. The draft width is 1.0 mm with an angle $\delta = 25^\circ$. The modified wave generator and the initial spatial arrangement of all components are critical to the method’s success. The initial positions are defined such that all parts are separated, ensuring zero initial penetration in the finite element model.

The kinematic theory governing the strain wave gear assembly and operation stems from the wave-like deformation of the neutral line of the flexspline. When the wave generator is inserted, it imposes a radial displacement field on the flexspline. For a classical elliptical generator, this displacement can be approximated relative to a base circle of radius $r_0$ as:

$$ w(\theta) = w_m \cos(2\theta) $$

where $w(\theta)$ is the radial displacement at angular position $\theta$, and $w_m$ is the maximum radial displacement (equal to $(d_a – d_b)/4$). This deformation profile is fundamental to the conjugate action of the strain wave gear teeth and will be compared against our dynamic simulation results.

Finite Element Model Development

The separate CAD components are imported into ANSYS for pre-processing. All parts are meshed using the explicit SOLID164 element, an 8-node hexahedral element suitable for large deformation and contact analysis. A carefully controlled, predominantly hexahedral mesh is generated to ensure accuracy and stability. The final model consists of approximately 130,000 nodes and 80,000 elements. Material properties are assigned as follows, detailed in Table 2.

| Component | Material | Density $\rho$ (kg/m³) | Young’s Modulus $E$ (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio $\nu$ | LS-DYNA Material Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexspline | 30CrMnSi Alloy Steel | 7850 | 206 | 0.29 | *MAT_ELASTIC (Linear Elastic) |

| Wave Generator | 45# Carbon Steel | 7850 | 210 | 0.30 | *MAT_RIGID |

| Circular Spline | 45# Carbon Steel | 7850 | 210 | 0.30 | *MAT_RIGID |

Modeling the wave generator and circular spline as rigid bodies is a common and efficient practice in strain wave gear simulation. It significantly reduces computational cost while maintaining high fidelity in the force-displacement response of the flexspline, which is the component of primary interest for stress and fatigue analysis. The flexspline is modeled as a linear elastic material, which is valid for simulating kinematic motion and stress distribution under nominal operating conditions, though plasticity models can be incorporated for overload studies.

Contact is the most crucial aspect of the strain wave gear model. Two primary contact pairs are defined using the *CONTACT_AUTOMATIC_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE keyword in LS-DYNA:

1. Contact Pair 1: The outer surface of the wave generator (target) and the inner surface of the flexspline barrel (contact).

2. Contact Pair 2: The tooth flanks of the circular spline (target) and the tooth flanks of the flexspline (contact).

Friction coefficients are assigned based on typical values for lubricated steel-on-steel contact, as shown in Table 3.

| Contact Pair | Target Surface | Contact Surface | Static Friction | Dynamic Friction | Contact Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wave Generator | Flexspline Inner Bore | 0.08 | 0.04 | Surface-to-Surface |

| 2 | Circular Spline Teeth | Flexspline Teeth | 0.03 | 0.02 | Surface-to-Surface |

Boundary conditions are applied to replicate the physical mounting of the strain wave gear. The back rim of the flexspline is fully fixed in all degrees of freedom (DOF), simulating its attachment to a rigid housing or output flange. The circular spline is constrained to allow only translation along the axial direction, mimicking a configuration where it is free to float axially during assembly but is rotationally fixed as the ground member. The wave generator is initially constrained in all rotational DOFs except for the final driving rotation, which is applied later.

Simulation Procedure: Assembly and Dynamics

The entire simulation is executed as a single analysis with multiple load steps, orchestrated via prescribed motions. This sequence is detailed in Table 4.

| Step | Time Interval (s) | Action | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0 – 0.001 | Wave Generator Axial Insertion | The wave generator is moved axially at constant velocity to close the gap $L_3$. The tapered ends guide the flexspline onto the major axis, dynamically assembling the wave generator-flexspline sub-assembly without penetration. |

| 2 | 0.001 – 0.0015 | Circular Spline Engagement | With the wave generator now statically deforming the flexspline, the circular spline is moved axially at constant velocity to close the gap $L_4$, engaging its teeth with the pre-deformed flexspline teeth. |

| 3 | 0.0016 – 0.30 | Dynamic Meshing | The assembly is complete. A constant angular velocity $\omega_{wg} = 200 \text{ rad/s}$ is prescribed to the wave generator about its axis. This drives the dynamic meshing cycle of the strain wave gear. |

The explicit dynamics formulation in LS-DYNA solves the equation of motion:

$$ \mathbf{M}\ddot{\mathbf{u}}(t) + \mathbf{C}\dot{\mathbf{u}}(t) + \mathbf{K}\mathbf{u}(t) = \mathbf{F}(t) $$

where $\mathbf{M}$ is the mass matrix, $\mathbf{C}$ is the damping matrix, $\mathbf{K}$ is the stiffness matrix, $\ddot{\mathbf{u}}$, $\dot{\mathbf{u}}$, $\mathbf{u}$ are the acceleration, velocity, and displacement vectors, and $\mathbf{F}$ is the external force vector. The explicit central difference method is conditionally stable, requiring a time step $\Delta t$ smaller than the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) condition based on the smallest element size and material wave speed: $\Delta t \le \frac{l_e}{c_d}$, where $l_e$ is the characteristic element length and $c_d = \sqrt{\frac{E}{\rho}}$ is the dilatational wave speed.

Results and Discussion

Kinematic Analysis: Motion Trajectories

The dynamic simulation provides a rich dataset for analyzing the complex motion of points on both the flexspline and the wave generator. To investigate the kinematics of the strain wave gear meshing, we track a specific node (Node 9005) located on the root circle of a flexspline tooth, initially positioned on the positive Y-axis (aligning with the wave generator’s major axis).

The X and Y-displacement histories of this node over the dynamic meshing phase are extracted. When these displacement components are plotted against each other, they reveal the planar trajectory of the node relative to the fixed global coordinate system. The resulting trajectory, shown conceptually by the data, forms a characteristic “teardrop” or elliptical-like closed loop. This loop represents the path of the flexspline material point as it is carried through one complete wave generator rotation. The shape of this trajectory is a direct consequence of the traveling wave deformation. The theoretical radial displacement $w(\theta)$ given earlier, combined with the rotational transformation, predicts a similar loopy path. The close agreement between the simulated trajectory and the classical theoretical approximation validates the fidelity of our assembly and dynamic simulation methodology for capturing the fundamental kinematics of the strain wave gear.

$$ x_{traj}(t) = -w_m \cos(2(\theta_0 – \omega_{fs} t)) \cdot \sin(\theta_0 – \omega_{fs} t) $$

$$ y_{traj}(t) = w_m \cos(2(\theta_0 – \omega_{fs} t)) \cdot \cos(\theta_0 – \omega_{fs} t) $$

where $\omega_{fs} = \omega_{wg} / \mu$ is the slow rotational speed of the flexspline, and $\theta_0$ is the initial angular position of the tracked point. While not a perfect match due to the discrete nature of tooth engagement and elastic distortions, the simulation captures this essential kinematic behavior.

Similarly, the motion of a node on the rigid wave generator (Node 1951) was tracked. Its displacement history shows near-perfect sinusoidal variation in the X and Y directions, consistent with a point on a purely rotating elliptical body, confirming the correct application of the rotational velocity boundary condition.

Structural Analysis: Stress in the Flexspline

The dynamic simulation also yields the time-varying stress field within the flexspline, which is critical for durability assessment. The von Mises stress is a key metric for evaluating yield propensity under multi-axial stress states. For a linear elastic material, the von Mises stress $\sigma_{vM}$ is calculated from the Cauchy stress tensor $\boldsymbol{\sigma}$ as:

$$ \sigma_{vM} = \sqrt{ \frac{(\sigma_{xx}-\sigma_{yy})^2 + (\sigma_{yy}-\sigma_{zz})^2 + (\sigma_{zz}-\sigma_{xx})^2 + 6(\tau_{xy}^2 + \tau_{yz}^2 + \tau_{zx}^2) }{2} } $$

During one full rotation of the wave generator, the stress field within the flexspline undergoes a complete cycle. The maximum stress concentrations are consistently observed in two primary locations, which migrate around the flexspline circumference in sync with the wave generator:

1. The Inner Surface of the Flexspline Barrel at the Major Axis Regions: This is where the bending deformation imposed by the wave generator is most severe. The stress here is primarily bending stress.

2. The Tooth Root Fillets of Engaged Teeth: This is a classic region of stress concentration due to the geometric notch effect, compounded by the bending load from transmitting torque.

The simulation successfully captures the propagation of these high-stress zones. At a given time instance, high von Mises stress is visible on the inner barrel surface near the instantaneous major axis of the wave generator. Simultaneously, high stress is evident at the root fillets of the teeth that are in full engagement near the minor axis region, where the relative motion between flexspline and circular spline teeth is minimal, and force transmission is maximal. As the wave generator rotates, these high-stress regions travel circumferentially, creating a cyclic, alternating stress state at every material point in the flexspline. This cyclic stress is the root cause of fatigue in strain wave gears, and the ability to accurately map its magnitude and distribution is a primary outcome of this dynamic simulation approach.

Conclusion and Future Work

This study has successfully demonstrated a robust and effective methodology for the virtual assembly and dynamic simulation of a strain wave gear using ANSYS/LS-DYNA explicit dynamics. The core achievement is the development of a pre-processing and multi-step simulation strategy that circumvents the critical issue of initial geometric penetration, a common showstopper for explicit analysis of pre-assembled strain wave gear models. By strategically modifying the wave generator geometry with tapered leads and simulating the axial assembly process prior to applying rotation, we establish a stable, physically valid initial condition for the dynamic meshing phase.

The results of the dynamic simulation provide valuable, high-fidelity insights that are difficult or impossible to obtain through analytical means alone. The kinematic trajectories of points on the flexspline confirm the fundamental wave motion principle of the strain wave gear, while the dynamic stress visualization reveals the traveling patterns of stress concentration, crucial for fatigue life prediction and design optimization. This methodology provides a powerful digital tool for analyzing strain wave gears, enabling engineers to study the effects of geometric parameters, materials, loads, and speeds on performance and durability without the need for physical prototypes.

Future work will focus on several extensions of this foundational model:

1. Material Non-Linearity: Incorporating elastoplastic or composite material models for the flexspline to study yield behavior and ultimate strength under extreme loads.

2. Advanced Contact and Friction: Implementing more sophisticated friction models that account for lubricant behavior and wear.

3. Thermo-Mechanical Coupling: Simulating the effects of frictional heat generation on the performance and stress state of the strain wave gear.

4. Parametric Optimization: Using this validated simulation framework as a component within a design optimization loop to automatically refine tooth profile, gear geometry, and material selection for specific performance targets (e.g., maximizing torque capacity, minimizing stress, or optimizing efficiency).

5. Dynamic Loading: Applying transient torque loads to the output (flexspline) to simulate real-world operational conditions like start-stop cycles and impact loads in robotic applications.

In conclusion, the integration of advanced explicit dynamics simulation with intelligent model setup techniques opens a new avenue for the in-depth analysis and development of high-performance strain wave gear transmissions, pushing the boundaries of their capability in next-generation precision mechanical systems.