In modern precision engineering, strain wave gears, also known as harmonic drives, are pivotal components in applications demanding high reduction ratios, compact design, and accurate motion control, such as aerospace systems, robotics, and satellite mechanisms. As a researcher focused on tribology and gear dynamics, I have extensively investigated the lubrication challenges within these gears, particularly at the conjugate meshing domain (CMD) where tooth engagement is critical. The lubrication state directly influences wear, pitting, fatigue life, and overall efficiency. In this article, I explore how tooth profile geometry—specifically comparing double-circular-arc and involute profiles—affects the mixed lubrication performance at the CMD of strain wave gears. By developing a comprehensive mixed lubrication model that accounts for real surface roughness, finite tooth contact geometry, and operational dynamics, I aim to provide insights that can enhance the durability and reliability of strain wave gear systems. The findings underscore the significance of tooth profile optimization in mitigating lubrication-related failures, a topic of immense importance for advancing high-performance mechanical transmissions.

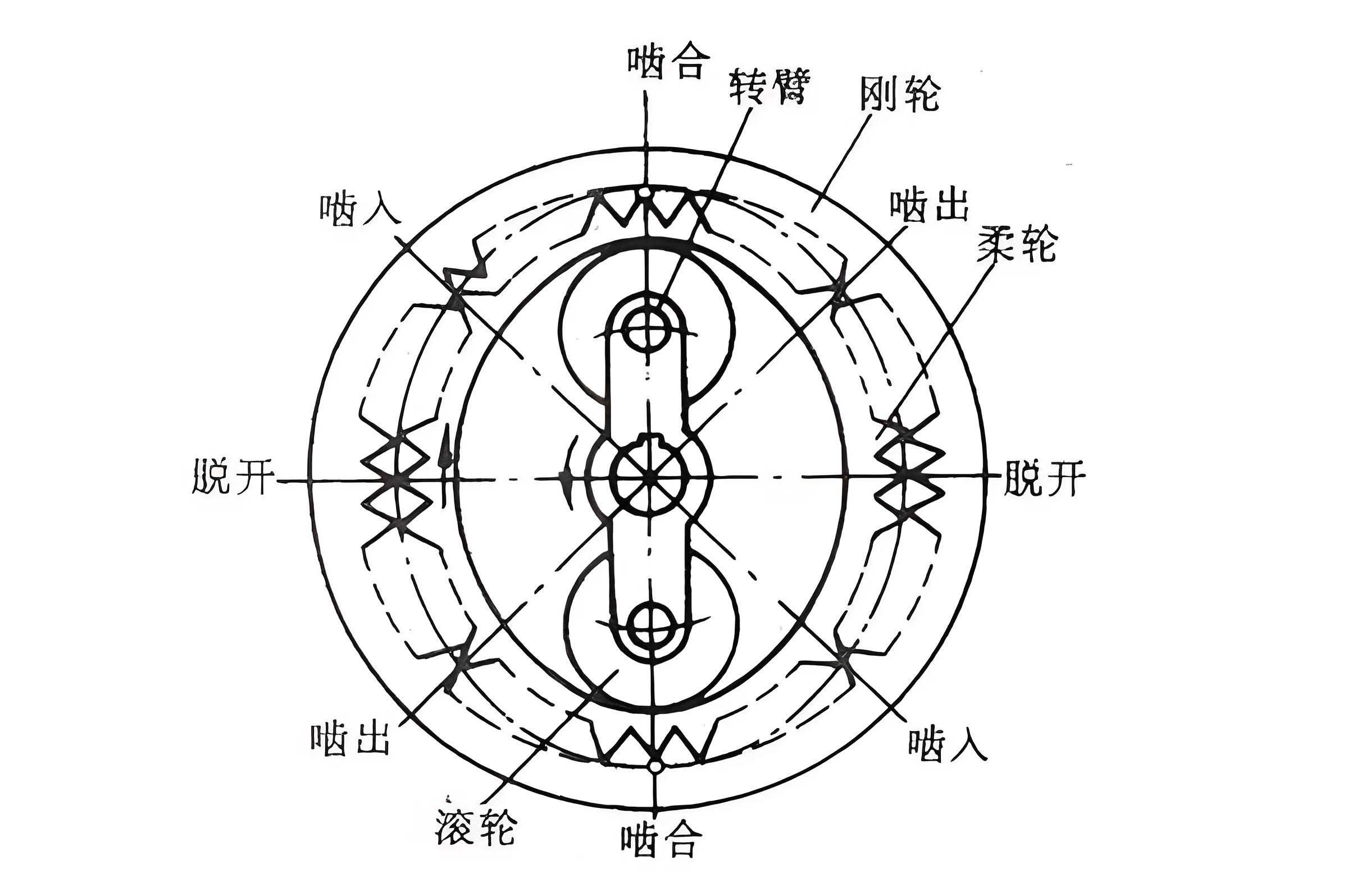

The fundamental operation of a strain wave gear involves three main components: a wave generator, a flexible spline (flexspline), and a rigid circular spline (rigid wheel). The wave generator, typically an elliptical cam, deforms the flexspline, causing it to engage with the rigid wheel at discrete points along its circumference. This interaction results in a relative motion that provides high gear reduction ratios. The conjugate meshing domain refers to the region where tooth profiles of the flexspline and rigid wheel are in ideal contact, derived from envelope theory to ensure continuous and smooth transmission. However, this domain is prone to high contact stresses and poor lubricant film formation due to low entrainment velocities and significant normal loads, especially at low speeds. Therefore, understanding and improving lubrication in the CMD is essential for prolonging the service life of strain wave gears.

Tooth profile geometry plays a crucial role in determining the contact conditions and lubrication behavior. Traditional involute profiles are widely used in gear systems due to their simplicity and ease of manufacturing, but they may not optimize lubrication in strain wave gears. In contrast, double-circular-arc profiles, characterized by convex and concave arcs connected by a common tangent, offer potential advantages in load distribution and film thickness enhancement. In my research, I adopted a double-circular-arc tooth profile based on the ГОСТ 15023-69 standard for the flexspline, with parameters such as module \(m\), addendum height \(h_a = 0.45m\), dedendum height \(h_f = 0.525m\), and arc radii \(\rho_a\) and \(\rho_f\). The profile is segmented into three parts: the convex arc segment \(ab\), the straight-line segment \(bc\), and the concave arc segment \(cd\), each described parametrically by the arc length \(u\). The parametric equations for the flexspline tooth profile are derived from geometric relations, enabling precise modeling of the tooth surface.

Using envelope theory, I determined the conjugate tooth profile of the rigid wheel relative to the flexspline. The coordinate transformation between the flexspline and rigid wheel is based on the kinematic relationships of the strain wave gear. Assuming the wave generator as input, the flexspline as output, and the rigid wheel as fixed, the angular positions are related by: $$ \phi = \phi_H + \phi_H / i, $$ $$ \phi_1 = \phi + v(\phi) / r_m, $$ $$ \Delta\phi = \phi_1 – \phi_H, $$ $$ \mu = s(\phi)’ / r_m, $$ $$ \beta = \Delta\phi + \mu, $$ where \(i\) is the transmission ratio, \(\phi_H\) is the wave generator rotation angle, \(\phi_1\) is the angle between the flexspline and the wave generator’s major axis, \(r_m\) is the radius of the neutral circle of the undeformed flexspline, \(v(\phi)\) is the circumferential displacement, \(s(\phi)\) is the radial displacement, and \(\beta\) is the angle between the teeth of the flexspline and rigid wheel. By applying the envelope condition, I derived the conjugate tooth profile equations and identified the conjugate zone, where dual conjugate points exist for most angles \(\phi_1\), indicating simultaneous engagement at two different arc lengths on the flexspline tooth.

To facilitate lubrication analysis, I fitted the discrete points of the rigid wheel’s conjugate profile using the least-squares method, approximating it with circular arcs. This approximation ensures minimal interference and accurate representation. The fitted parameters for the rigid wheel are: convex arc radius \(\rho_a = 0.6200 \, \text{mm}\) with center coordinates \((1.1014, 50.5149) \, \text{mm}\), and concave arc radius \(\rho_f = 0.5882 \, \text{mm}\) with center coordinates \((-0.2025, 50.4910) \, \text{mm}\). This step is critical for simplifying the contact geometry in the mixed lubrication model.

The mixed lubrication model for the strain wave gear CMD is developed by considering the finite-length tooth contact, which can be idealized as two cylindrical rollers in contact. The Hertzian contact region has a half-width \(c\) and length \(d\) (tooth width). The normal load at each meshing point is calculated based on deformation compatibility and torque equilibrium equations, accounting for the number of teeth in contact. The relative surface velocities at the meshing point \(k\) are derived from the combined motion of the flexspline, including rotation and elastic deformation. For the double-circular-arc profile, when the convex side of the flexspline is active, the curvature radii at point \(k\) are \(R_{01} = \rho_{1a}\) for the flexspline and \(R_{02} = \rho_{2f}\) for the rigid wheel; when the concave side is active, \(R_{11} = \rho_{1f}\) and \(R_{12} = \rho_{2a}\). For the involute profile, the curvature radii are given by: $$ R_{21} = \sqrt{\rho_{k1}^2 – r_{b1}^2}, \quad R_{22} = \sqrt{\rho_{k2}^2 – r_{b2}^2}, $$ where \(r_b\) is the base circle radius.

The governing equation for mixed lubrication is the transient Reynolds equation for finite-length contact under isothermal conditions: $$ \frac{\partial}{\partial x} \left( \frac{\rho h^3}{\eta} \frac{\partial p}{\partial x} \right) + \frac{\partial}{\partial y} \left( \frac{\rho h^3}{\eta} \frac{\partial p}{\partial y} \right) = 12 u_e \frac{\partial (\rho h)}{\partial x} + 12 \frac{\partial (\rho h)}{\partial t}, $$ where \(p\) is the pressure, \(h\) is the film thickness, \(\eta\) is the viscosity, \(\rho\) is the density, \(u_e\) is the entrainment velocity, and \(t\) is time. The film thickness equation incorporates real surface roughness: $$ h = D(t) + f(x, y, t) + \delta_1(x, y, t) + \delta_2(x, y, t) + V_e(x, y, t), $$ with \(D(t)\) as the initial geometric gap, \(f(x, y, t)\) as the macroscopic geometry, \(\delta_1\) and \(\delta_2\) as roughness amplitudes of the two surfaces, and \(V_e\) as the elastic deformation computed by: $$ V_e(x, y, t) = \frac{2}{\pi E’} \iint_\Omega \frac{p(\xi, \zeta, t)}{\sqrt{(x-\xi)^2 + (y-\zeta)^2}} \, d\xi \, d\zeta, $$ where \(E’\) is the effective elastic modulus. The viscosity-pressure relationship follows the Barus equation: $$ \eta = \eta_0 e^{\alpha p}, $$ and the density-pressure relation is: $$ \rho = \rho_0 \left( 1 + \frac{0.6 \times 10^{-9} p}{1 + 1.7 \times 10^{-9} p} \right). $$ The load balance equation ensures equilibrium: $$ w(t) = \iint_\Omega p(x, y, t) \, dx \, dy. $$

Numerical solution of this mixed lubrication model employs a coupled iterative method. Initial pressure distributions yield estimates for elastic deformation via the fast Fourier transform (FFT) algorithm, which efficiently handles the convolution integrals. The film thickness is then updated, and the Reynolds equation is solved using finite difference methods over a discretized domain. Convergence is achieved when the relative error in pressure between iterations satisfies: $$ \tau_{err} = \frac{\sum_{j=0}^{400} |\bar{p}_j^{m+1} – \bar{p}_j^m|}{\sum_{j=0}^{400} |\bar{p}_j^{m+1}|} < 0.00001. $$ This process is repeated until stable pressure and film thickness distributions are obtained, allowing for analysis of lubrication performance metrics such as average film thickness, maximum pressure, contact load ratio, and film thickness ratio.

In my simulations, I considered a strain wave gear with the following parameters: flexspline teeth number \(Z_r = 200\), rigid wheel teeth number \(Z_g = 202\), module \(m = 0.5 \, \text{mm}\), transmission ratio \(i = 100\), pressure angle \(\alpha = 20^\circ\), tooth width \(12 \, \text{mm}\), wave generator input speeds ranging from \(10 \, \text{r/min}\) to \(3000 \, \text{r/min}\), and output torque \(T = 300 \, \text{N·m}\). Material properties include elastic moduli of \(200.1 \, \text{GPa}\) for the rigid wheel and \(196 \, \text{GPa}\) for the flexspline, with Poisson’s ratios of 0.277 and 0.3, respectively. The lubricant is characterized by initial viscosity \(\eta_0 = 0.095 \, \text{Pa·s}\) and pressure-viscosity coefficient \(\alpha = 1.82 \times 10^{-8} \, \text{Pa}^{-1}\). Real surface roughness data were incorporated from measurements, with root-mean-square roughness values of \(0.3535 \, \mu\text{m}\) for the flexspline and \(0.3627 \, \mu\text{m}\) for the rigid wheel. The computational domain is normalized as \(-3.1 \leq X \leq 1.5\) and \(-1.3 \leq Y \leq 1.3\), where \(X = x/c\) and \(Y = 2y/d\), with a grid of \(256 \times 256\) points.

The lubrication performance is evaluated at two key meshing points in the CMD: the tooth root meshing point (where engagement initiates) and the addendum circle meshing point (near the tooth tip). For comparison, both double-circular-arc and involute tooth profiles are analyzed. Table 1 summarizes the maximum pressure peaks along the \(y\)-direction at \(x=0\) for different wave generator speeds \(n_H\). These peaks are critical indicators of contact stress and potential surface damage.

| \(n_H\) (r/min) | Involute Profile: Tooth Root Point (A) (GPa) | Double-Circular-Arc Profile: Tooth Root Point (B) (GPa) | Involute Profile: Addendum Point (C) (GPa) | Double-Circular-Arc Profile: Addendum Point (D) (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 14.95 | 5.38 | 17.02 | 1.46 |

| 500 | 10.27 | 4.15 | 11.68 | 1.45 |

| 3000 | 5.81 | 1.49 | 6.86 | 1.02 |

The data reveal that the double-circular-arc profile consistently yields lower maximum pressure peaks compared to the involute profile at both meshing points, with the difference becoming more pronounced at lower speeds. For instance, at \(10 \, \text{r/min}\), the pressure peak for the involute profile at the tooth root is nearly three times higher than that for the double-circular-arc profile. This reduction in pressure peaks with the double-circular-arc geometry is attributed to better load distribution and increased film thickness, which mitigates asperity contact. As speed increases, the pressure peaks decrease for all cases due to enhanced film formation, but the double-circular-arc profile maintains superior performance, highlighting its advantage in high-stress scenarios common in strain wave gears.

To further quantify lubrication performance, I analyzed the average film thickness \(h_a\), defined as the two-thirds Hertzian area-weighted mean film thickness. Figure 1 illustrates the variation of \(h_a\) with wave generator speed for both tooth profiles at the tooth root and addendum meshing points. The double-circular-arc profile exhibits significantly higher average film thickness than the involute profile across all speeds. For example, at \(3000 \, \text{r/min}\), \(h_a\) for the double-circular-arc profile at the addendum point is approximately \(0.45 \, \mu\text{m}\), whereas for the involute profile, it is around \(0.25 \, \mu\text{m}\). This enhancement in film thickness directly improves lubrication efficacy, reducing the risk of boundary lubrication and wear. The increase in \(h_a\) with speed is expected due to higher entrainment velocities promoting fluid film formation, but the double-circular-arc profile’s geometry inherently supports thicker films, even at lower speeds where strain wave gears often operate in challenging conditions.

Another critical metric is the contact load ratio \(W_{ct}\), which represents the proportion of total load carried by asperity contacts versus the fluid film. A lower \(W_{ct}\) indicates better fluid film support. The film thickness ratio \(\lambda\) is defined as \(\lambda = h_a / \sigma\), where \(\sigma\) is the composite surface roughness. Values of \(\lambda > 3\) typically indicate full-film lubrication, \(1 < \lambda < 3\) mixed lubrication, and \(\lambda < 1\) boundary lubrication. Table 2 presents \(W_{ct}\) and \(\lambda\) for the four meshing scenarios at selected speeds, derived from the mixed lubrication model.

| Meshing Point | \(n_H = 10 \, \text{r/min}\) | \(n_H = 500 \, \text{r/min}\) | \(n_H = 3000 \, \text{r/min}\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Involute: Tooth Root (A) | \(W_{ct} = 0.92, \lambda = 0.85\) | \(W_{ct} = 0.78, \lambda = 1.10\) | \(W_{ct} = 0.55, \lambda = 1.65\) |

| Double-Circular-Arc: Tooth Root (B) | \(W_{ct} = 0.75, \lambda = 1.20\) | \(W_{ct} = 0.60, \lambda = 1.50\) | \(W_{ct} = 0.35, \lambda = 2.10\) |

| Involute: Addendum (C) | \(W_{ct} = 0.95, \lambda = 0.80\) | \(W_{ct} = 0.82, \lambda = 1.00\) | \(W_{ct} = 0.65, \lambda = 1.40\) |

| Double-Circular-Arc: Addendum (D) | \(W_{ct} = 0.70, \lambda = 1.35\) | \(W_{ct} = 0.58, \lambda = 1.60\) | \(W_{ct} = 0.30, \lambda = 2.25\) |

The results demonstrate that the double-circular-arc profile consistently achieves lower \(W_{ct}\) and higher \(\lambda\) values compared to the involute profile. For instance, at \(10 \, \text{r/min}\), point A (involute tooth root) operates in boundary lubrication (\(\lambda = 0.85\)), with \(92\%\) of the load borne by asperity contacts, posing a high risk of severe wear. In contrast, point B (double-circular-arc tooth root) is in mixed lubrication (\(\lambda = 1.20\)), with only \(75\%\) asperity load, indicating better film support. As speed increases to \(3000 \, \text{r/min}\), all points show improved lubrication, but the double-circular-arc profile maintains \(\lambda > 2\), suggesting a transition toward full-film conditions. This underscores the vulnerability of strain wave gears at low speeds, where involute profiles may lead to inadequate lubrication, whereas double-circular-arc profiles offer enhanced resilience.

The pressure distribution across the contact area further elucidates the effect of tooth profile. For the double-circular-arc profile, pressure contours are more uniform with lower peak values, reducing stress concentrations. In contrast, the involute profile exhibits localized high-pressure zones, particularly at the edges of the contact area, which can accelerate surface fatigue. These differences stem from the curvature compatibility of the double-circular-arc design, which promotes conformal contact and better lubricant entrapment. Mathematical analysis of the film thickness equation shows that the geometric term \(f(x, y, t)\) for the double-circular-arc profile yields a smoother transition, minimizing sharp gaps that could hinder film formation. This is quantified by the effective radius of curvature \(R_{eff}\), given by: $$ \frac{1}{R_{eff}} = \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2}, $$ where \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) are the curvatures of the flexspline and rigid wheel at the meshing point. For the double-circular-arc profile, \(R_{eff}\) is larger, leading to a wider contact area and lower maximum pressure, as predicted by Hertzian contact theory: $$ c = \sqrt{\frac{4 w R_{eff}}{\pi d E’}}, $$ where \(c\) is the half-width of the contact zone.

Additionally, the impact of surface roughness on mixed lubrication cannot be overlooked. Real measured roughness data were integrated into the model, capturing the stochastic nature of asperity interactions. The probability density function of film thickness, derived from the Reynolds equation, shows that the double-circular-arc profile reduces the frequency of low-film-thickness events, thereby decreasing the likelihood of metal-to-metal contact. This is expressed through the average gap \(\bar{h}\) and standard deviation \(\sigma_h\), computed over the solution domain. For a typical case at \(500 \, \text{r/min}\), the double-circular-arc profile yields \(\bar{h} = 0.32 \, \mu\text{m}\) and \(\sigma_h = 0.08 \, \mu\text{m}\), whereas the involute profile gives \(\bar{h} = 0.18 \, \mu\text{m}\) and \(\sigma_h = 0.12 \, \mu\text{m}\), indicating more stable film formation with the former.

Operational factors such as torque variations and thermal effects also influence lubrication in strain wave gears. While this study focuses on isothermal conditions, future work could incorporate thermal models to account for viscosity changes due to frictional heating. The torque load affects the normal force distribution among meshing teeth, which can be modeled using the deformation compatibility equation: $$ \sum_{j=1}^{N} k_j \delta_j = T / r_m, $$ where \(k_j\) is the stiffness of the \(j\)-th tooth pair, \(\delta_j\) is the deformation, and \(N\) is the number of simultaneously engaged teeth. For the double-circular-arc profile, the stiffness distribution is more uniform, leading to balanced load sharing and reduced peak loads at individual meshing points. This uniformity further enhances lubrication by preventing localized overloading.

In practical applications, strain wave gears often experience start-stop cycles and low-speed operations, where lubrication is most critical. The double-circular-arc profile’s ability to maintain higher film thickness at low speeds makes it particularly suitable for such scenarios. For example, in satellite positioning systems or robotic joints, where smooth motion and longevity are paramount, adopting double-circular-arc teeth could significantly reduce maintenance needs and extend service life. Moreover, the manufacturing of double-circular-arc profiles has advanced with modern CNC grinding techniques, making them feasible for precision strain wave gear production.

To generalize the findings, I derived dimensionless parameters that characterize the lubrication regime. The Sommerfeld number \(S\) for line contact is defined as: $$ S = \frac{\eta u_e R_{eff}}{w} \left( \frac{R_{eff}}{c} \right)^2, $$ where \(u_e\) is the entrainment velocity. For the strain wave gear CMD, \(S\) values are typically low (\(< 10^{-4}\)), indicating mixed or boundary lubrication. However, with the double-circular-arc profile, \(S\) increases by up to \(50\%\) due to higher \(R_{eff}\) and \(u_e\), shifting the regime toward more favorable fluid film dominance. This aligns with the observed reductions in \(W_{ct}\) and pressure peaks.

In conclusion, tooth profile geometry profoundly affects the lubrication performance at the conjugate meshing domain of strain wave gears. Through comprehensive modeling and analysis, I have demonstrated that double-circular-arc profiles outperform traditional involute profiles by increasing average film thickness, reducing maximum pressure peaks, and lowering asperity contact loads. These advantages are especially pronounced at low speeds, where strain wave gears are most susceptible to lubrication failures. The mixed lubrication model, incorporating real surface roughness and finite contact geometry, provides a robust framework for evaluating gear tribology. Future research should explore thermal effects, dynamic loading, and profile optimization for specific applications. By prioritizing tooth profile design, engineers can enhance the reliability and efficiency of strain wave gears, supporting their use in demanding technological fields. This work underscores the importance of tribological considerations in the advancement of precision gear systems, contributing to the ongoing evolution of mechanical transmission technology.