Strain wave gearing, a revolutionary power transmission concept, has established itself as a critical technology in modern precision engineering. Its unique operating principle, predicated on the controlled elastic deformation of a flexible component, enables performance characteristics unattainable by conventional geared systems. Since its conceptual inception and subsequent patenting, the strain wave gear has evolved from a novel idea to a cornerstone component in fields demanding compactness, high reduction ratios, and exceptional positional accuracy, such as robotics, aerospace, and semiconductor manufacturing. This article provides a comprehensive, first-person overview of the technology, delving into its fundamental principles, historical development, and the multifaceted contemporary research landscape that continues to push its boundaries.

Fundamental Principles and Characteristics

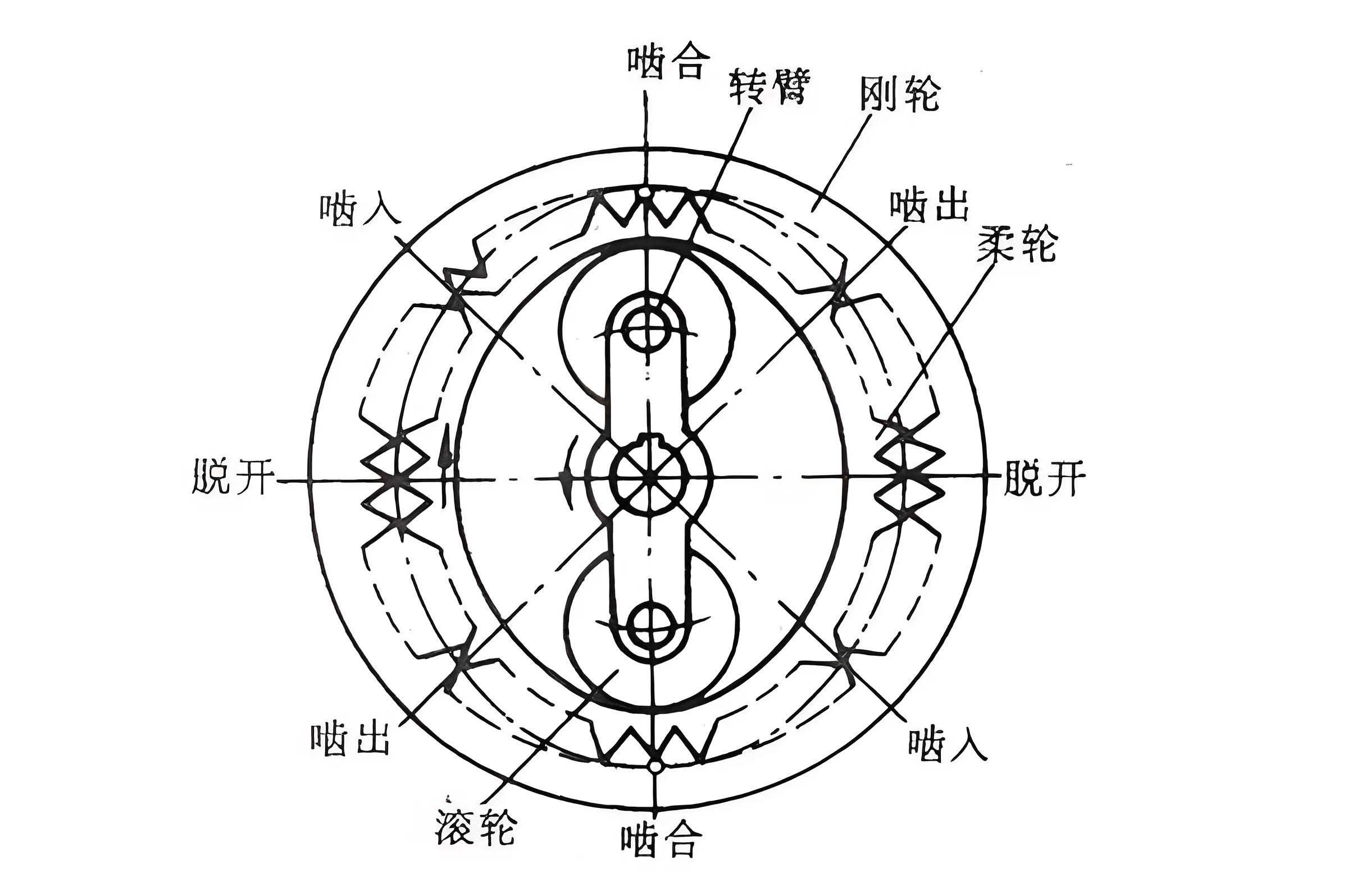

At its core, a strain wave gear system operates on a fascinating principle of elastic kinematics. It comprises three primary elements: a rigid circular spline (the circular spline), a flexible circular spline (the flexspline), and a wave generator. The wave generator, typically an elliptical cam or a set of rotating bearings, is inserted into the flexspline, causing it to deform into a controlled, non-axisymmetric shape. This deformation forces the teeth of the flexspline to engage with the teeth of the circular spline at two diametrically opposed regions.

The key to the high reduction ratio lies in the slight difference in the number of teeth between the two splines. As the wave generator rotates, the region of engagement progresses. However, because the flexspline has fewer teeth (typically by 2, 4, or more) than the circular spline, each full rotation of the wave generator results in only a small angular displacement of the flexspline relative to the circular spline. The fundamental kinematic relationship is given by:

$$

i = -\frac{N_f}{N_c – N_f}

$$

where \( i \) is the reduction ratio (wave generator input to flexspline output), \( N_f \) is the number of teeth on the flexspline, and \( N_c \) is the number of teeth on the circular spline. The negative sign indicates that the output rotation is opposite to the input. For a configuration where the circular spline is fixed and the flexspline outputs rotation, the ratio becomes:

$$

i = \frac{N_f}{(N_c – N_f)}

$$

This simple yet ingenious mechanism yields a suite of remarkable advantages. Strain wave gears offer exceptionally high single-stage reduction ratios (often 30:1 to 320:1), compact size and low mass, high positional accuracy and repeatability, zero-backlash operation (when properly preloaded), high torque capacity for their size, and coaxial input/output alignment. These characteristics make the strain wave gear, also commonly known as the harmonic drive, indispensable in applications ranging from robotic joint actuators and satellite pointing mechanisms to precision medical devices and machine tool axes.

Historical Development and Global Landscape

The genesis of the strain wave gear concept is credited to mid-20th-century engineering. The theoretical groundwork involving elastic deformation for motion transfer was laid in the late 1940s. The practical invention of the device as we recognize it today, however, was achieved in the 1950s with the seminal work of C.W. Musser in the United States, leading to a patented design. This innovation was initially driven by the demanding requirements of aerospace and defense applications, which valued its compactness and precision.

The subsequent decades saw rapid global development and specialization:

| Region/Country | Key Developments and Focus |

|---|---|

| United States | Pioneering work and early patents (USM Company). Initial standardization and series production for both military and civilian use. Focus on high-reliability space applications. |

| Soviet Union / Russia | Comprehensive theoretical research in institutes. Development of circular arc tooth profiles. Establishment of national standards for strain wave gear reducers. |

| Japan | Commercialization and mass-production leadership (e.g., Harmonic Drive Systems Inc.). Advanced tooth profile development (e.g., “S” tooth, evolved cup designs). Dominance in the industrial robotics market. Global expansion through subsidiaries and partnerships. |

| Europe | Diverse research across nations (Germany, France, UK, Switzerland, Italy). Focus on precision engineering applications, micro-system integration (e.g., LIGA process for micro gears), and novel actuation principles (e.g., magnetic strain wave gears). |

| China | Technology introduction in the 1960s, followed by significant domestic R&D. Establishment of research laboratories and national standards (GB/T). Growing industrial capacity with companies targeting the robotics market. Active research on new tooth profiles (e.g., CTC, P-type) and optimization techniques. |

This global effort has transformed the strain wave gear from a specialized aerospace component into a widely available, standardized mechanical element, with continuous innovation driven by new application demands.

Contemporary Research Frontiers

Despite its maturity, the strain wave gear remains a fertile ground for research. Current investigations are deeply interdisciplinary, combining advanced mechanics, materials science, manufacturing engineering, and control theory to enhance performance, reliability, and applicability.

1. Meshing Theory and Tooth Profile Optimization

The heart of a strain wave gear’s performance lies in its tooth meshing behavior. Early profiles like the straight-sided or standard involute teeth were simplifications that did not fully account for the complex, load-induced deformations of the flexspline. Modern research focuses on deriving precise conjugate tooth profiles that ensure optimal contact conditions under load, maximizing load distribution and minimizing stress concentrations.

Analytical methods like the envelope method, the theory of gearing using the “B-matrix” approach, and kinematic simulation are employed to generate these profiles. The goal is to define a flexspline tooth shape such that its envelope of motion, under the deformation imposed by the wave generator, perfectly matches the conjugate circular spline tooth profile. The contact path and transmission error can be modeled as functions of the tooth profile parameters \( \theta \) and deformation \( \delta \):

$$

\text{Contact Path} = f(\theta, \delta, \text{Profile Geometry})

$$

$$

\text{Transmission Error} = \phi_{output} – \frac{\phi_{input}}{i}

$$

This has led to the development and refinement of specialized tooth profiles, summarized below:

| Tooth Profile Type | Key Characteristics and Advantages | Research/Application Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Involute | Standard, easier to manufacture. Prone to edge contact under load, leading to higher stress. | Baseline for comparison; used in many standard designs. |

| Circular Arc / Double Circular Arc | Superior load distribution, higher contact ratio, reduced bending stress at the tooth root. Allows for adjustable backlash control. | Widely adopted in high-performance commercial strain wave gears. Research on optimal arc radii and pressure angles. |

| “S” Tooth / Conjugate Tooth Profile | Specifically designed for harmonic drives. Aims for perfect or near-perfect conjugate action under deformation. | Proprietary designs (e.g., by Harmonic Drive Systems). Focus on maximizing simultaneous tooth pair contact. |

| “P” Type / “CTC” Type | Modern optimized profiles. Features low tooth height, wide tooth width, and large root fillet. Designed to increase torsional stiffness, torque capacity, and flexspline fatigue life. | Active area of research and commercial development (e.g., in Chinese industry). Finite Element Analysis (FEA) used extensively for validation. |

| Parametric/Spline-Based | Using B-splines or other parametric curves to define the tooth flank, allowing for multi-variable optimization of the contact pattern and stress state. | Academic research focused on developing flexible, optimization-friendly profile definitions. |

2. Flexspline Strength, Fatigue, and Structural Optimization

The flexspline is the most critical and life-limiting component in a strain wave gear. It undergoes cyclic elastic deformation, leading to multi-axial stress states that drive fatigue failure. Research in this area employs a three-pronged approach: theoretical analysis, experimental testing, and computational simulation.

- Theoretical Models: Based on thin-shell elasticity theory, these models approximate the flexspline as a cylindrical shell to calculate membrane and bending stresses. The stress at a critical point (often the cup rim or tooth root) can be expressed as a function of geometry, material properties, and load:

$$

\sigma_{max} = K_t \cdot \left( \frac{E \cdot t \cdot \delta}{R^2} + C \cdot \frac{T}{A \cdot R} \right)

$$

where \( K_t \) is a stress concentration factor, \( E \) is Young’s modulus, \( t \) is wall thickness, \( \delta \) is radial deformation, \( R \) is mean radius, \( C \) is a torque coefficient, \( T \) is transmitted torque, and \( A \) is a cross-sectional area.

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA): This is the dominant tool for detailed stress analysis. Advanced nonlinear FEA models incorporate contact, large deformations, and material plasticity. They are used to map stress distributions, identify weak points, and perform parametric studies to optimize geometry (cup length, wall thickness transitions, tooth fillet radius, diaphragm shape).

- Structural Optimization: Using FEA results within optimization algorithms (e.g., topology optimization, parametric optimization with response surface methodology) to find the best compromise between weight, stiffness, and fatigue life. Key objectives often include minimizing the peak von Mises stress \( \sigma_{vM}^{max} \) or maximizing the safety factor \( SF \) against fatigue.

$$

\text{Minimize: } \sigma_{vM}^{max}(\mathbf{x}) \quad \text{Subject to: } V(\mathbf{x}) \leq V_0, \quad \delta(\mathbf{x}) \geq \delta_{min}

$$

where \( \mathbf{x} \) is a vector of design variables (e.g., \( t_{cup}, r_{fillet}, L_{cup} \)), \( V \) is volume, and \( \delta \) is a stiffness-related displacement.

3. Transmission Accuracy and Error Modeling

For precision applications like robotics, understanding and minimizing transmission error (TE) is paramount. TE is the deviation between the actual output position and the ideal position predicted by the kinematic ratio. Sources of error in a strain wave gear are complex and include:

- Manufacturing errors (tooth profile deviations, pitch errors, eccentricity).

- Assembly errors (wave generator misalignment, bearing clearance).

- Elastic deformation under load (time-varying torsional stiffness, hysteresis).

- Thermal effects.

Research focuses on creating comprehensive error models that aggregate these sources. A simplified static model might sum contributions:

$$

TE_{total} = TE_{manufacturing} + TE_{assembly} + \Delta \theta_{torsion}(T)

$$

where \( \Delta \theta_{torsion}(T) \) is the angular deflection due to torsional compliance as a function of torque \( T \). Dynamic models incorporate these errors into the equations of motion of a drive system. Experimental techniques like laser interferometry or high-resolution encoders are used to measure TE spectra, which guide both design improvements and precision manufacturing processes.

4. Dynamic Characteristics and Nonlinear Modeling

As strain wave gears are deployed in high-bandwidth servo systems, their dynamic behavior becomes critical. The nonlinear stiffness, damping, and friction within the gear can induce resonance, limit cycle oscillations, and impact control stability. Research involves developing high-fidelity dynamic models.

A typical lumped-parameter torsional model for a servo system with a strain wave gear might be:

$$

J_m \ddot{\theta}_m + b_m \dot{\theta}_m = \tau_m – \tau_g

$$

$$

\tau_g = K(\Delta\theta) \cdot (\theta_m/i – \theta_l) + D(\Delta\dot{\theta}) \cdot (\dot{\theta}_m/i – \dot{\theta}_l) + \tau_{friction}(\dot{\theta}_m/i – \dot{\theta}_l)

$$

$$

J_l \ddot{\theta}_l + b_l \dot{\theta}_l = \tau_g – \tau_{load}

$$

Here, \( J_m, J_l \) are motor and load inertias, \( \theta_m, \theta_l \) are positions, \( b_m, b_l \) are damping coefficients, \( \tau_m, \tau_g, \tau_{load} \) are motor, gear, and load torques. The core complexity lies in modeling the gear torque \( \tau_g \), which depends nonlinearly on the deflection \( \Delta\theta \) and its rate \( \Delta\dot{\theta} \):

- Stiffness \( K(\Delta\theta) \): Non-linear, hysteretic, and often modeled as a polynomial or piecewise function.

- Damping \( D(\Delta\dot{\theta}) \): Combines material hysteresis and viscous effects.

- Friction \( \tau_{friction} \): Includes pre-sliding (Dahl, LuGre models) and sliding regimes.

Identifying these parameters and validating the model against experimental frequency response data is a key research activity to predict and mitigate unwanted dynamic phenomena.

5. Advanced Materials and Manufacturing

Breaking from traditional alloy steels, researchers are exploring novel materials to enhance strain wave gear performance. Composite materials, particularly carbon-fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRP) for the flexspline cup body (with metallic teeth), offer higher specific stiffness and superior damping characteristics, potentially reducing vibration and acoustic noise. Additive manufacturing (3D printing) is being investigated for prototyping complex flexspline geometries or creating integrated lightweight structures.

Manufacturing processes are also advancing. Beyond conventional hobbing and shaping, processes like precision skiving for teeth, high-speed dry cutting, and fine blanking are being adopted to improve accuracy and surface finish. For micro strain wave gears, photochemical machining and LIGA-like processes are essential for creating high-aspect-ratio teeth on miniature flexsplines.

6. New Frontiers: Miniaturization and Novel Actuation

The principles of the strain wave gear are being extended to new scales and domains.

- Micro Strain Wave Gears: Devices with outer diameters below 10 mm are being developed for micro-robotics and precision instrumentation. This presents immense challenges in micro-machining, assembly, and modeling of scale-dependent material behavior.

- Magnetic and Piezoelectric Strain Wave Gears: These “gearless” actuators replace the mechanical wave generator with a rotating magnetic field or traveling ultrasonic waves that directly induce the traveling deformation wave in the flexspline. This eliminates mechanical wear in the wave generator and can enable operation in vacuum or extreme environments. The torque transmission in a magnetic strain wave gear can be related to magnetic flux \( \Phi \) and structural stiffness:

$$

\tau \propto \frac{\partial W_m}{\partial \theta}, \quad W_m = \int \frac{B^2}{2\mu} dV

$$

where \( W_m \) is magnetostatic co-energy, \( B \) is magnetic flux density, and \( \mu \) is permeability.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

In my analysis, the strain wave gear stands as a testament to the power of innovative mechanical design. From its theoretical origins to its current status as a high-tech commodity, its journey has been shaped by relentless global research and development. Today, the technology is being refined on multiple fronts: through advanced conjugate tooth profiles that enhance load capacity and efficiency; through sophisticated FEA and optimization tools that extend fatigue life and minimize weight; through dynamic modeling that ensures stability in high-performance servo loops; and through explorations into new materials and actuation principles.

Looking forward, several challenges and opportunities persist. The pursuit of ever-higher power density pushes the limits of flexspline fatigue strength, demanding better materials and surface treatments. The trend towards ultra-compact, “pancake” designs with very short flexsplines intensifies stress concentrations, requiring novel structural solutions. Achieving consistent, sub-arc-minute accuracy at high volume production remains a manufacturing challenge. Furthermore, fully integrating the nonlinear dynamic model of the strain wave gear into real-time motion controllers to achieve ultimate tracking performance is an ongoing research goal in mechatronics.

The convergence of these research streams—enabled by advancements in computational power, material science, and precision metrology—ensures that the strain wave gear will continue to evolve. It will remain a key enabling technology as robotics becomes more pervasive, as space exploration advances, and as the demand for miniaturized, intelligent mechanical systems grows across all sectors of industry. The fundamental elegance of using controlled elastic deformation for motion transmission, the core idea of the strain wave gear, promises to inspire solutions to engineering challenges for decades to come.