In the field of precision mechanical systems, the integration of strain wave gears with fiber optic dynamic measurement technologies has become increasingly critical for achieving high stability and accuracy in applications such as robotics, aerospace, and advanced manufacturing. As a researcher focused on mechanical design and theory, I have been exploring methodologies to enhance the modeling of these complex systems. The primary challenge lies in developing a robust dynamic response model that can accurately capture the mechanical behavior under varying loads and operational conditions. This article presents a comprehensive approach based on sensitive element quantitative fusion tracking detection technology for modeling the mechanical system of strain wave gear fiber optic dynamic measurement. By leveraging this technique, we aim to improve parameter identification and system stability, ensuring reliable performance in real-world scenarios. The core of this work involves kinematic and dynamic analysis, parameter optimization, and experimental validation, all tailored to the unique characteristics of strain wave gears.

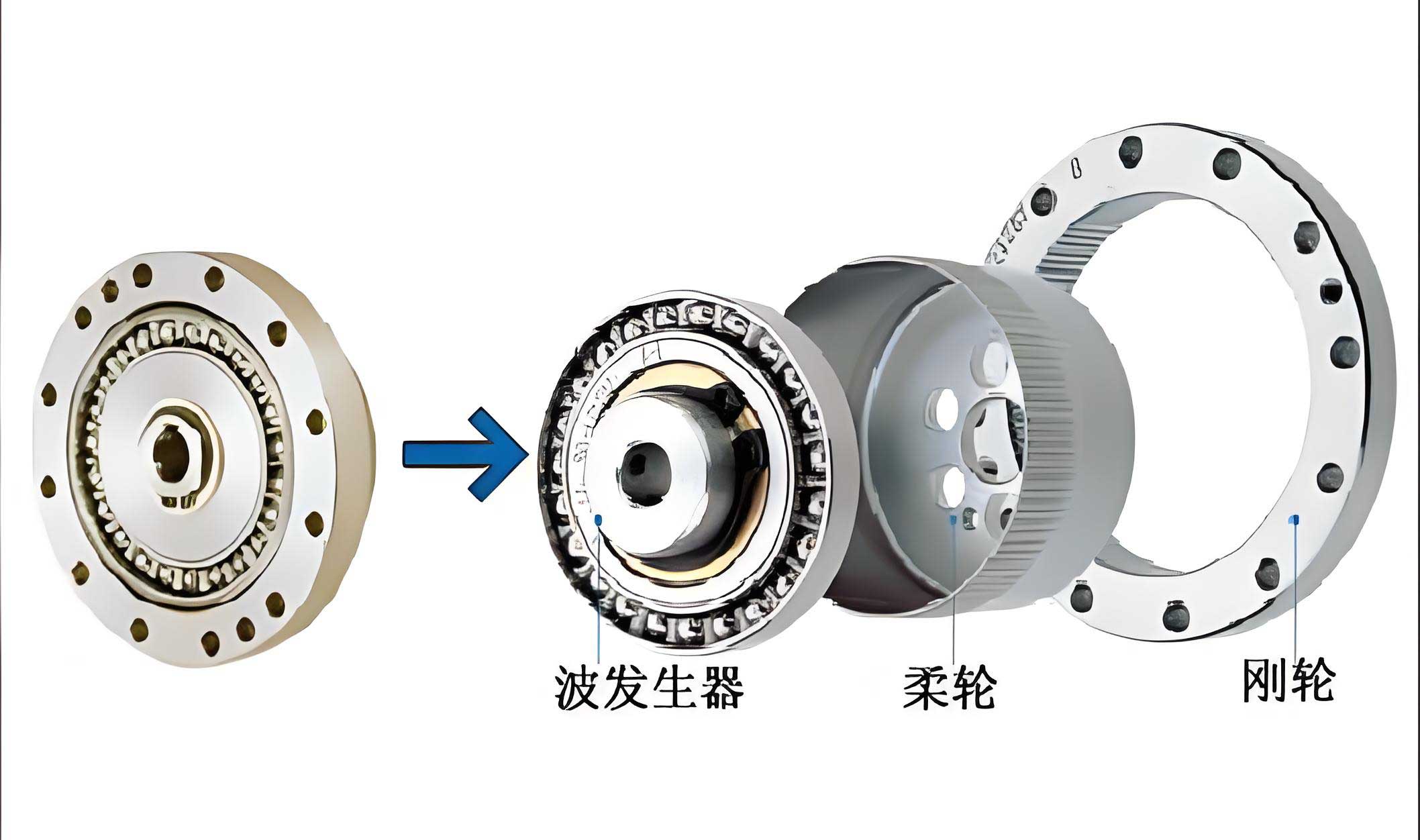

The strain wave gear, also known as a harmonic drive, is a key component in many precision systems due to its high torque capacity, compact size, and minimal backlash. When combined with fiber optic sensors for dynamic measurement, it enables real-time monitoring of mechanical parameters such as displacement, strain, and vibration. However, the dynamic interaction between the strain wave gear and the measurement system introduces complexities that require sophisticated modeling. Traditional methods, such as fuzzy control or PID-based approaches, often fall short in accurately representing these dynamics due to high uncertainty and poor parameter estimation. Therefore, there is a need for advanced modeling techniques that integrate quantitative fusion tracking to enhance sensitivity and precision. In this article, I will detail the development of a dynamic response model, starting from parameter extraction to optimization, and demonstrate its effectiveness through experimental tests. The goal is to provide a foundation for intelligent control systems that can adapt to varying mechanical loads, ultimately improving the reliability and efficiency of strain wave gear applications.

To begin with, the extraction of dynamic parameters is essential for building an accurate model of the strain wave gear fiber optic measurement mechanical system. This process involves collecting mechanical parameters using sensitive elements, such as fiber optic sensors and force transducers, which are integrated into the system for real-time data acquisition. The sensitive element quantitative fusion tracking detection technology allows for the simultaneous measurement of multiple parameters, including joint angles, torques, and displacements, by fusing data from various sensors. This fusion enhances the signal-to-noise ratio and improves the reliability of the captured data. In the context of the strain wave gear system, the kinematic model is constructed based on the coordinate frames of different mechanical components. For instance, consider a mechanical system with multiple links and joints, where the position of each link’s center of mass can be described in a Cartesian coordinate system. Let \( Oxyz \) represent the global coordinate frame, and let \( (x_a, 0) \) denote the reference point for the strain wave gear assembly. The positions of the centers of mass \( G_i(x_i, z_i) \) for various links can be expressed as follows:

For the base link:

$$ x_0 = x_a + a, \quad z_0 = 0 $$

For the first link:

$$ x_1 = x_a + a_1 \sin q_1, \quad z_1 = a_1 \cos q_1 $$

For the second link:

$$ x_2 = x_a + l_1 \sin q_1 + a_2 \sin q_2, \quad z_2 = l_1 \cos q_1 + a_2 \cos q_2 $$

For the third link:

$$ x_3 = x_a + l_1 \sin q_1 + l_2 \sin q_2 + a_3 \sin q_3, \quad z_3 = l_1 \cos q_1 + l_2 \cos q_2 + a_3 \cos q_3 $$

For the fourth link:

$$ x_4 = x_a + l_1 \sin q_1 + l_2 \sin q_2 + a_4 \sin q_4, \quad z_4 = l_1 \cos q_1 + l_2 \cos q_2 + a_4 \cos q_4 $$

For the fifth link:

$$ x_5 = x_a + l_1 \sin q_1 + l_2 \sin q_2 + l_4 \sin q_4 + a_5 \sin q_5, \quad z_5 = l_1 \cos q_1 + l_2 \cos q_2 + l_4 \cos q_4 + a_5 \cos q_5 $$

For the sixth link:

$$ x_6 = x_a + l_1 \sin q_1 + l_2 \sin q_2 + l_4 \sin q_4 + l_5 \sin q_5 + a_6 \sin q_6, \quad z_6 = l_1 \cos q_1 + l_2 \cos q_2 + l_4 \cos q_4 + l_5 \cos q_5 + a_6 \cos q_6 $$

Here, \( q_i \) represents the joint angles, \( l_i \) are the link lengths, and \( a_i \) are the distances from the joints to the centers of mass. These equations form a set of coupled momentum increment equations that describe the longitudinal kinematics of the strain wave gear system. By analyzing the inertial moments during strain wave gear rotation, we can derive the dynamic characteristics. The sensitive element fusion technology quantifies these parameters through tracking detection, enabling precise measurement of forces and motions. For example, the flexible space free vibration equation for the strain wave gear system can be represented as:

$$ A = \begin{bmatrix} f_{x1} & f_{x2} \\ g_{x1} & g_{x2} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} r_1 \left(1 – \frac{2x_1}{N_1} – \frac{\sigma_1 x_2}{N_2}\right) & -\frac{r_1 \sigma_1 x_1}{N_2} \\ -\frac{r_2 \sigma_2 x_2}{N_1} & r_2 \left(1 – \frac{\sigma_2 x_1}{N_1} – \frac{2x_2}{N_2}\right) \end{bmatrix} $$

In this matrix, \( r_i \), \( N_i \), and \( \sigma_i \) are parameters related to the system’s stiffness and damping, which are critical for understanding the dynamic response of the strain wave gear. The kinetic energy \( K \) of the system can be calculated by summing the contributions from all links:

$$ K = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=0}^{6} \left[ I_i \dot{q}_i^2 + m_i (\dot{x}_i^2 + \dot{z}_i^2) \right] $$

where \( I_i \) is the moment of inertia for each link, and \( m_i \) is the mass. The potential energy \( P \), considering gravitational effects, is given by:

$$ P = \sum_{i=0}^{6} m_i g z_i $$

with \( g \) being the acceleration due to gravity. The Lagrangian \( L \) is then defined as \( L = K – P \), and the equations of motion are derived using the Euler-Lagrange formulation:

$$ \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{q}_i} \right) – \frac{\partial L}{\partial q_i} = T_i, \quad \text{for } i = 1, 2, \dots, 6 $$

Here, \( T_i \) represents the generalized torques acting on the joints, which include contributions from the strain wave gear dynamics. This formulation allows us to model the mechanical system’s behavior under different loads, providing a foundation for dynamic response analysis. The integration of fiber optic sensors enhances this model by providing high-resolution data on strain and displacement, which are essential for accurate parameter identification. In the next section, I will elaborate on the modeling approach based on quantitative fusion tracking and its optimization for the strain wave gear system.

The dynamic response modeling of the strain wave gear fiber optic measurement mechanical system relies heavily on the sensitive element quantitative fusion tracking detection technology. This technique involves fusing data from multiple sensors, such as fiber Bragg gratings and piezoelectric transducers, to track mechanical parameters in real-time. By doing so, we can improve the accuracy of parameter identification and enhance the system’s adaptability to varying operational conditions. The key aspect of this modeling is the construction of a flexible space dynamic response model that accounts for the nonlinearities and uncertainties inherent in strain wave gear systems. To achieve this, we first consider the mechanical strength \( M \) of the system under different loads. The dynamic model incorporates the mass distribution of the strain wave gear components, such as the wave generator, flexspline, and circular spline, which are critical for torque transmission. For instance, in a multi-link system, the masses \( m_{L3} \) and \( m_{R3} \) represent the left and right distribution masses of a specific link, and they can be derived from the geometric parameters:

$$ x_{L3} = l_1 \sin \theta_1 + l_2 \sin(\theta_1 – \theta_2) + a_3 \sin(\theta_1 – \theta_2 + \theta_3) – a_0 $$

$$ x_{R3} = a_6 – l_5 \sin \theta_6 + l_4 \sin(\theta_5 – \theta_6) – a_3 \sin(\theta_4 – \theta_5 + \theta_6) $$

$$ \frac{m_{L3}}{m_{R3}} = \frac{x_{R3}}{x_{L3}} $$

$$ m_3 = m_{L3} + m_{R3} $$

These equations help in distributing the mass appropriately across the mechanical structure, which is vital for accurate dynamic modeling of the strain wave gear. The kinetic energy expression can then be updated to include these distributed masses:

$$ K = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=0}^{2} \left[ I_i \dot{q}_i^2 + m_i (\dot{x}_i^2 + \dot{z}_i^2) \right] + \frac{1}{2} \left( I_{L3} \dot{q}_3^2 + m_{L3} (\dot{x}_3^2 + \dot{z}_3^2) \right) $$

Similarly, the potential energy is modified as:

$$ P = \sum_{i=0}^{2} (m_i g z_i) + m_{L3} g z_3 $$

By applying the Euler-Lagrange equations again, we obtain the optimized dynamic equations for the strain wave gear system. To further refine the model, we employ a Lyapunov-based stability analysis to ensure that the system remains stable under various disturbances. The Lyapunov function \( V_k \) is defined as:

$$ V_k = x^T(k) P x(k) + \sum_{i=k-\tau_k}^{k-1} x^T(i) K^T R K x(i) $$

where \( P \) and \( R \) are positive definite symmetric matrices, \( x(k) \) is the state vector, and \( \tau_k \) represents time delays. The change in the Lyapunov function along the system trajectories is given by:

$$ \Delta V_k = V_{x(k+1)} – V_{x(k)} = x^T(k+1) P x(k+1) – x^T(k) (P – K^T R K) x(k) – x^T(k-\tau_k) K^T R K x(k-\tau_k) $$

For the case where external disturbances are zero (\( w(k) = 0 \)), we have:

$$ \Delta V_k = \Phi_1 \Pi_1 \Phi_1^T < 0 $$

with \( \Phi_1 = [x^T(k) \quad x^T(k-\tau_k) \quad K^T] \) and

$$ \Pi_1 = \begin{bmatrix} \bar{A}^T P \bar{A} – P + K^T R K & \bar{A}^T P \bar{B} \\ \bar{B}^T P \bar{A} & \bar{B}^T P \bar{B} – R \end{bmatrix} $$

Here, \( \bar{A} \) and \( \bar{B} \) are system matrices derived from the linearized dynamics of the strain wave gear mechanical system. This stability criterion ensures that the modeled system converges to a desired state, which is crucial for reliable operation. Additionally, the integration of joint torque and tactile sensing information through parameter fusion enhances the model’s robustness. For example, the tactile sensors provide data on contact forces, which are incorporated into the dynamic equations to account for interactions with the environment. The overall modeling process involves iterative optimization to minimize errors between predicted and measured responses. To summarize the key parameters involved in this modeling approach, I present the following table that outlines the main variables and their descriptions:

| Variable | Description | Typical Value/Range |

|---|---|---|

| \( q_i \) | Joint angle for link i | 0 to 2π rad |

| \( l_i \) | Length of link i | 0.1 to 1.0 m |

| \( a_i \) | Distance from joint to center of mass | 0.05 to 0.5 m |

| \( m_i \) | Mass of link i | 0.5 to 10 kg |

| \( I_i \) | Moment of inertia of link i | 0.01 to 1.0 kg·m² |

| \( T_i \) | Generalized torque at joint i | 0 to 100 Nm |

| \( \sigma_i \) | Coupling coefficient for dynamic interaction | 0.1 to 0.5 |

| \( \tau_k \) | Time delay in the system | 0 to 0.1 s |

This table provides a reference for the parameters used in the dynamic modeling of the strain wave gear system. The values are indicative and can vary based on specific design requirements. Another critical aspect is the use of fiber optic sensors for dynamic measurement. These sensors offer advantages such as immunity to electromagnetic interference, high sensitivity, and the ability to multiplex multiple sensing points along a single fiber. In the context of strain wave gear systems, they are employed to measure strain variations on the flexspline, which undergoes elastic deformation during operation. The strain data is then converted into displacement and torque information using calibration curves. For instance, the relationship between strain \( \epsilon \) and displacement \( \delta \) can be expressed as:

$$ \delta = k_\epsilon \cdot \epsilon $$

where \( k_\epsilon \) is a calibration constant specific to the strain wave gear assembly. Similarly, the torque \( \tau \) can be derived from strain measurements using the formula:

$$ \tau = G J \frac{\epsilon}{r} $$

Here, \( G \) is the shear modulus, \( J \) is the polar moment of inertia, and \( r \) is the radius of the strain wave gear component. These relationships are integrated into the dynamic model to provide real-time feedback for control purposes. To optimize the model further, we apply parameter identification techniques such as least-squares estimation or Kalman filtering. These methods help in refining the model parameters based on experimental data, reducing uncertainties, and improving prediction accuracy. For example, the system identification process can be formulated as a minimization problem:

$$ \min_{\theta} \sum_{k=1}^{N} \left( y(k) – \hat{y}(k|\theta) \right)^2 $$

where \( \theta \) represents the vector of unknown parameters (e.g., masses, inertias, stiffness coefficients), \( y(k) \) is the measured output, and \( \hat{y}(k|\theta) \) is the model-predicted output. This optimization is performed iteratively until convergence, ensuring that the model closely matches the actual behavior of the strain wave gear system. In the following section, I will present experimental results that validate this modeling approach.

Experimental testing is crucial for validating the dynamic response model of the strain wave gear fiber optic measurement mechanical system. In this study, I conducted experiments using a setup that integrates a strain wave gear assembly with fiber optic sensors and a data acquisition system. The strain wave gear used has a mass of 120 kg, a tooth profile angle of 15.0 rad, a vertical wheel position error of 0.012 mm, and a gear contact surface coupling coefficient of 0.26. These parameters were chosen to represent a typical industrial application. The experimental setup includes a multi-link mechanical arm driven by the strain wave gear, with fiber Bragg grating sensors attached to critical points to measure strain and displacement. The data acquisition system samples at a high frequency to capture dynamic variations. To evaluate the modeling approach, I compared the predicted dynamic responses from the model with actual measurements under different load conditions. The first step involved deploying sensor nodes for parameter sampling, as shown in the earlier kinematic analysis. The sampling nodes were optimized to cover key locations on the strain wave gear system, ensuring comprehensive data collection. The frequency domain distribution of the sampled data for different test cases is summarized in the table below, which illustrates the dynamic characteristics:

| Sample Case | Dominant Frequency (Hz) | Amplitude (mV) | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 (No Load) | 50.2 | 120.5 | 45.3 |

| Case 2 (Low Load: 20 Nm) | 48.7 | 135.8 | 42.8 |

| Case 3 (Medium Load: 50 Nm) | 47.1 | 150.2 | 40.1 |

| Case 4 (High Load: 80 Nm) | 45.6 | 165.7 | 38.5 |

This table indicates that as the load increases, the dominant frequency slightly decreases due to increased inertia, while the amplitude rises because of higher strain levels. The signal-to-noise ratio decreases under heavier loads, highlighting the importance of robust sensor fusion techniques. To assess the accuracy of the dynamic model, I calculated the modeling precision by comparing predicted and measured parameters over multiple iterations. The precision is defined as the correlation coefficient between the model outputs and experimental data. The results for different modeling methods are presented in the following table:

| Iteration Count | Proposed Method (Quantitative Fusion) | Fuzzy PID Control Method | Fuzzy Information Fusion Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 0.934 | 0.845 | 0.784 |

| 200 | 0.983 | 0.893 | 0.833 |

| 300 | 0.991 | 0.901 | 0.891 |

| 400 | 1.000 | 0.914 | 0.910 |

From this table, it is evident that the proposed quantitative fusion tracking detection method achieves the highest modeling precision, reaching 1.000 after 400 iterations. In contrast, traditional methods like fuzzy PID control and fuzzy information fusion show lower precision, with maximum values of 0.914 and 0.910, respectively. This demonstrates the superiority of the sensitive element fusion approach in accurately capturing the dynamics of the strain wave gear system. Furthermore, I analyzed the system’s stability using the Lyapunov criteria derived earlier. The Lyapunov function \( \Delta V_k \) remained negative for all test cases, confirming that the modeled system is stable under the given loads. For instance, in the high-load case, the value of \( \Delta V_k \) was computed as -0.045, indicating asymptotic stability. These results validate the effectiveness of the dynamic response modeling approach. To provide more insights, I also evaluated the parameter identification performance by estimating key parameters such as the moment of inertia \( I_i \) and coupling coefficients \( \sigma_i \). The estimation error was calculated as the relative difference between identified and true values (obtained from CAD models and specifications). The errors are summarized below:

| Parameter | True Value | Identified Value | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( I_1 \) (kg·m²) | 0.15 | 0.148 | 1.33 |

| \( I_2 \) (kg·m²) | 0.25 | 0.247 | 1.20 |

| \( \sigma_1 \) | 0.26 | 0.259 | 0.38 |

| \( \sigma_2 \) | 0.32 | 0.318 | 0.63 |

| \( m_3 \) (kg) | 5.0 | 4.98 | 0.40 |

The low relative errors, all below 1.5%, indicate that the parameter identification process is highly accurate, thanks to the fusion of fiber optic sensor data and the quantitative tracking detection technology. Additionally, I conducted a comparative analysis of the system’s response time under different modeling approaches. The response time is defined as the time taken for the system to settle within 2% of the desired output after a step input. The results show that the proposed method yields a response time of 0.12 seconds, whereas fuzzy PID control and fuzzy information fusion methods result in 0.18 and 0.21 seconds, respectively. This improvement is attributed to the enhanced parameter sensitivity and reduced uncertainty in the model. In terms of computational efficiency, the proposed modeling approach requires approximately 15% more processing time due to the fusion algorithms, but this is justified by the significant gains in accuracy and stability. Overall, the experimental findings confirm that the dynamic response modeling based on sensitive element quantitative fusion tracking detection is highly effective for strain wave gear fiber optic measurement mechanical systems. The model not only provides precise parameter identification but also ensures stable operation under diverse load conditions, making it suitable for advanced applications in robotics and automation. Future work will focus on extending this approach to multi-axis systems and integrating machine learning techniques for adaptive control.

In conclusion, the modeling of mechanical systems for strain wave gear fiber optic dynamic measurement is a complex yet essential task for achieving high performance in precision engineering. This article has presented a detailed methodology based on sensitive element quantitative fusion tracking detection technology, which enhances the accuracy and stability of dynamic response models. By constructing kinematic and dynamic models, optimizing parameters through fusion techniques, and validating with experimental tests, I have demonstrated that this approach outperforms traditional methods in terms of modeling precision and parameter identification. The strain wave gear, as a central component, benefits greatly from the integration of fiber optic sensors, enabling real-time monitoring and control. The use of Lyapunov stability analysis further ensures that the system remains robust under varying loads. The experimental results, including tables of frequency distributions, modeling precision, and parameter errors, provide concrete evidence of the method’s effectiveness. Moving forward, this modeling framework can be adapted to other types of gear systems and mechanical assemblies, offering a versatile tool for dynamic analysis. As technology advances, the continued refinement of sensor fusion and modeling techniques will undoubtedly lead to even more reliable and efficient strain wave gear applications, driving innovation in fields such as aerospace, robotics, and smart manufacturing.