The strain wave gear drive, a revolutionary transmission mechanism based on elastic deformation theory, has become indispensable in fields demanding high precision, compactness, and reliability, such as robotics, aerospace, and optical instrumentation. Its operation fundamentally relies on the controlled periodic elastic deformation of a flexible spline, a process initiated and sustained by a critical component: the flexible bearing. This bearing is subjected to severe and continuous elliptical deformation, making its dynamic response and contact behavior pivotal to the overall system’s load capacity, transmission accuracy, and operational lifespan. Failures, particularly fatigue fracture of the outer ring, often originate here. Therefore, a profound understanding of the dynamic and contact characteristics of the flexible bearing is essential for advancing the design and durability of strain wave gear systems. This article presents a comprehensive nonlinear finite element analysis, leveraging explicit dynamics to simulate the complex interactions within a deformed flexible bearing under operational conditions.

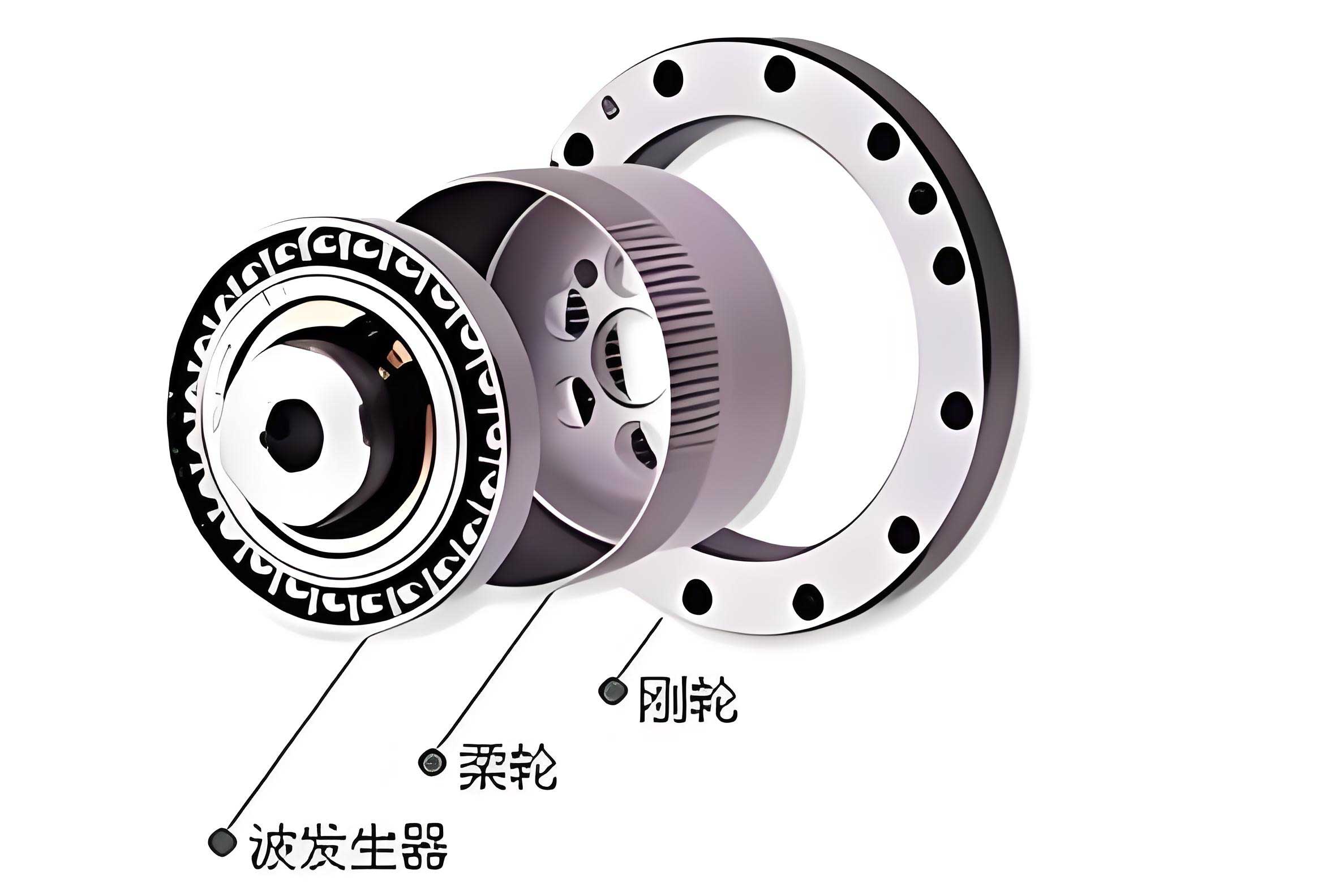

Strain wave gear transmission operates on a simple yet elegant principle involving three primary components: a circular spline, a flexible spline, and a wave generator. The wave generator, typically an elliptical cam, is assembled inside a thin-walled flexible bearing. This assembly is then fitted into the flexible spline, forcing it into an elliptical shape. The flexible spline meshes with the rigid circular spline at two diametrically opposite regions along the major axis of the ellipse. As the wave generator rotates, the elliptical deformation zone propagates, creating a traveling wave of elastic strain in the flexible spline. This results in a slow relative rotation between the flexible and circular splines. The flexible bearing is the linchpin of this mechanism; its outer ring conforms to the elliptical wave generator, while its inner ring typically rotates with the input shaft. The rolling elements within the bearing facilitate this motion while transmitting load, all while the entire bearing structure undergoes cyclic elastic deformation. This unique operating environment subjects the bearing components, especially the outer ring and rolling elements, to non-uniform and time-varying stresses unlike those in conventional rotary bearings.

To initiate the analysis, a precise geometric model of the pre-deformed flexible bearing assembly must be established. For this study, a model 3E905KAT2* flexible bearing is considered, operating with an elliptical cam wave generator. The key dimensions are summarized in Table 1. The initial deformed state is defined by the equidistant curve of the standard ellipse. Given an elliptic cam, the outer raceway of the flexible bearing assumes an elliptical profile post-assembly. The major axis diameter ($D_{major}$) and minor axis diameter ($D_{minor}$) of this deformed outer ring can be derived from the nominal bearing geometry and the radial deformation factor. A 3D assembly model, with appropriate transparency for visualization, forms the basis for subsequent meshing and analysis.

| Structural Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Bearing Width | 5.0 | mm |

| Bore Diameter (Inner Race) | 24.0 | mm |

| Outside Diameter (Nominal Outer Race) | 32.0 | mm |

| Ball Diameter | 3.0 | mm |

| Number of Balls | 21 | – |

| Outer Raceway Groove Curvature Radius | 1.62 | mm |

| Inner Raceway Groove Curvature Radius | 1.56 | mm |

The finite element model is constructed to capture the highly nonlinear contact dynamics. The explicit dynamics solver LS-DYNA via ANSYS is employed for its robustness in handling complex, transient contact events. The component definitions are as follows:

- Element Type: The rolling elements, inner ring, outer ring, and cage are discretized using the 8-node solid element, SOLID164. However, as this element lacks rotational degrees of freedom, the surface of the inner and outer rings are additionally coated with shell elements (SHELL163) to facilitate the application of rotational velocity constraints.

- Material Models: The outer ring and rolling balls, which experience severe cyclic elastic deformation and are prone to fatigue, are modeled as linear isotropic elastic materials (e.g., ZGCr15 steel). Properties include Young’s Modulus $E = 2.06 \times 10^{11}$ Pa and Poisson’s ratio $\nu = 0.3$. The inner ring, which undergoes a single, static deformation during assembly, and the nylon cage are modeled as rigid bodies to significantly reduce computational cost without sacrificing critical interaction fidelity.

- Meshing Strategy: A hybrid meshing approach ensures accuracy and efficiency. The cage is meshed with free quadrilateral elements. The inner and outer rings are meshed using a swept method with hexahedral elements. The rolling balls are meshed with mapped hexahedral elements. Crucially, the mesh is refined in the outer ring and rolling ball contact zones to accurately resolve stress gradients. The final model comprises approximately 49,582 nodes and 48,675 elements.

The contact interactions are the core of the simulation. Three primary contact pairs are defined using the automatic surface-to-surface (ASTS) algorithm in LS-DYNA:

1. Rolling Ball vs. Outer Ring

2. Rolling Ball vs. Inner Ring

3. Rolling Ball vs. Cage

These definitions account for friction and separation. The boundary and loading conditions simulate a typical operating scenario for a strain wave gear bearing: a fixed outer ring and a rotating inner ring. The constraints are detailed in Table 2.

| Component | Translational Constraint | Rotational Constraint |

|---|---|---|

| Inner Ring | Fixed in Z-direction | Free in X, Y |

| Outer Ring | Fixed in Z-direction | Fixed in X, Y, Z |

| Cage | Fixed in Z-direction | Free in X, Y |

The load application sequence is staged for numerical stability. First, a rotational speed of $\omega = 500$ rpm (approximately $52.36$ rad/s) is applied to the inner ring. After a short settling period ($t = 0.002$ s), a radial load $F_r$ is applied linearly from 0 N to 200 N at the outer ring, concentrated in the major axis region to simulate the reaction from the meshing gear teeth in the strain wave gear assembly. The simulation time is sufficient to capture several full revolutions and the stabilized dynamic response.

Analysis of Dynamic Characteristics

The motion of the deformed bearing components is complex, involving superimposed rigid-body and elastic motions. To analyze this, nodes on the outer ring at the major and minor axis positions, and specific elements on rolling balls at different angular positions relative to the major axis, are tracked.

Outer Ring Dynamic Response: The radial displacement of nodes on the outer ring’s major and minor axes oscillates with equal magnitude but in opposite phase. This confirms the preserved elliptical deformation shape during rotation. The displacement amplitude $\Delta r$ is approximately 0.3 mm, consistent with the prescribed radial deformation of the strain wave gear. The velocity of these nodes, however, exhibits a fluctuating profile with alternating peaks and troughs. This fluctuation is not due to gross rigid-body motion (the outer ring is fixed) but is induced by the discrete, periodic contact forces from the passing rolling balls and their interaction with the cage pockets. The velocity magnitude and fluctuation pattern are essentially identical for nodes at different positions on the ellipse, indicating a consistent dynamic excitation mechanism around the circumference.

The velocity $v_{node}(t)$ can be conceptually described as a response to a series of impulse forces from the rolling elements:

$$ v_{node}(t) = \sum_{i=1}^{N_b} h(t – \tau_i) * F_{contact,i}(t) $$

where $N_b$ is the number of balls, $h(t)$ is the impulse response function of the outer ring structure, $\tau_i$ are the times of contact events, and $F_{contact,i}$ are the contact force histories.

Rolling Ball Dynamic Response: The motion of a rolling ball is a combination of planetary motion (revolution around the bearing axis) and spin about its own axis. The displacement curve of a ball element shows a high-frequency oscillation superimposed on a steadily increasing trend. The oscillatory component represents the ball’s spin and its orbital motion within the variable-clearance elliptical raceway, while the steady increase corresponds to its revolution with the cage. The velocity analysis is particularly revealing. The velocity of a ball element fluctuates cyclically between a high peak and a low trough. The peak velocity corresponds to the instant when the ball is in contact with the rotating inner race, and its value approaches the tangential velocity of the inner race contact point. The trough velocity occurs when the ball is in contact with the stationary outer race. The formula for the theoretical maximum (spin) velocity of a ball in a simple bearing is adapted for the elliptical case:

$$ \omega_{ball, spin} \approx \frac{R_{inner}}{r_{ball}} \cdot \omega_{inner} \cdot \left(1 – \frac{\delta(\theta)}{D_{pw}}\right) $$

where $R_{inner}$ is the inner race radius, $r_{ball}$ is the ball radius, $\omega_{inner}$ is the inner race speed, $\delta(\theta)$ is the radial deformation as a function of angular position $\theta$, and $D_{pw}$ is the pitch diameter. The term $(1 – \delta(\theta)/D_{pw})$ modulates the spin speed based on local deformation. Crucially, the mean velocity and the amplitude of velocity fluctuation decrease for balls located farther from the major axis towards the minor axis. This is because the relative slip between the ball and the races varies with the local conformity and load distribution imposed by the elliptical deformation in the strain wave gear assembly.

Analysis of Contact Characteristics

The contact stress and force distributions are paramount for assessing fatigue life and load distribution in the flexible bearing of a strain wave gear.

Stress Distribution in the Outer Ring and Rolling Balls: The von Mises stress distribution at a given time instant clearly shows a highly non-uniform pattern. Stress is heavily concentrated in the outer ring region near the major axis of the ellipse, where the radial load is applied and the deformation is maximal. The stress value attenuates progressively towards the minor axis. The maximum equivalent stress $\sigma_{max}$ on the outer ring is found to be approximately 272.6 MPa near the major axis contact zone, while it drops to as low as 11.37 MPa near the minor axis. The stress history for a material point on the outer ring at the major axis shows intermittent, sharp spikes. These spikes correspond directly to the passage of individual rolling balls through the high-load zone. The stress for a point at the minor axis also shows fluctuations but with much lower magnitude and a slight phase lag relative to the major axis stress, reflecting the propagation of the deformation wave.

The contact stress $\sigma_c$ between a ball and a raceway can be estimated by the classic Hertzian contact theory, though the elliptical deformation modifies the effective curvature:

$$ \sigma_{c, max} = \frac{3Q}{2\pi a b} $$

$$ a = \alpha \sqrt[3]{\frac{3Q}{2E’} \sum \rho} , \quad b = \beta \sqrt[3]{\frac{3Q}{2E’} \sum \rho} $$

where $Q$ is the contact load, $a$ and $b$ are the semi-major and semi-minor axes of the contact ellipse, $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are coefficients dependent on the curvature difference, $\sum \rho$ is the sum of principal curvatures, and $E’$ is the equivalent elastic modulus. In the flexible bearing, $Q$ varies dramatically with angular position $\theta$.

Similarly, the rolling balls experience their highest stress when they traverse the major axis region. The stress on a ball element cycles between high and low values. The high-stress peaks occur during contact with the inner race under load, and the lower peaks occur during contact with the outer race. A ball’s stress history over several revolutions shows distinct high-stress periods (when orbiting through the major axis sector) and low-stress periods (when orbiting through the minor axis sector). The maximum ball stress observed was approximately 2.03 GPa, occurring at the ball-inner race contact in the major axis zone.

Contact Force Analysis: The time-history of contact forces at the three interfaces provides direct insight into load sharing and dynamic loading. The contact forces between the rolling balls and both the inner and outer rings are nearly identical in magnitude and exhibit large, synchronized fluctuations. Their mean value closely matches the applied external radial load divided by the number of balls in the load zone ($\approx 5$ balls), confirming static equilibrium. The fluctuation amplitude is significant, driven by the varying compliance of the bearing as balls enter and exit the loaded elliptical region—a phenomenon inherent to the operation of the strain wave gear. In contrast, the contact force between the rolling balls and the cage is considerably smaller in magnitude and shows much less volatility. This force is primarily associated with guiding the balls and is less affected by the large radial load fluctuations.

The fluctuating contact force $Q_i(t)$ on the $i$-th ball can be related to the radial deflection $\delta(\theta_i)$ at its angular position $\theta_i = \omega_c t + \phi_i$, where $\omega_c$ is the cage speed and $\phi_i$ is the initial phase. For a nonlinear Hertzian contact, the force-deflection relationship is:

$$ Q_i(t) = K_n \cdot [\delta(\theta_i(t)) – \delta_0]_+^{3/2} $$

where $K_n$ is the contact stiffness constant, $\delta_0$ is any initial clearance, and $[x]_+$ denotes the positive part (i.e., no force if there is no contact). The elliptical radial deflection profile $\delta(\theta)$ is the source of the periodic fluctuation.

| Characteristic | Observation | Key Value / Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Outer Ring Radial Displacement | Opposite phase at major/minor axis, equal amplitude. | Amplitude $\Delta r \approx 0.3$ mm |

| Rolling Ball Velocity | Alternating peaks (inner race contact) and troughs (outer race contact). Decreases from major to minor axis. | Modulated by $\delta(\theta)$ |

| Outer Ring Stress | Concentrated near major axis, attenuates to minor axis. Fluctuates with ball passage. | $\sigma_{max} \approx 272.6$ MPa, $\sigma_{min} \approx 11.4$ MPa |

| Rolling Ball Stress | Maximum at ball-inner race contact on major axis. Cycles between high/low stress zones. | $\sigma_{ball, max} \approx 2.03$ GPa |

| Ball-Race Contact Force | Large fluctuations, mean equals external load share. | $Q_{mean} \approx F_r / N_{load-zone}$ |

| Ball-Cage Contact Force | Smaller magnitude, low volatility. | Relatively constant |

Conclusion

This detailed nonlinear finite element analysis provides critical insights into the operational behavior of the flexible bearing, a component whose performance is fundamental to the strain wave gear. The simulation reveals that the dynamic characteristics of the outer ring are uniform circumferentially in terms of fluctuation pattern, but the magnitude of motion and stress is dictated by the elliptical deformation field. The rolling balls exhibit a complex velocity profile that is a direct consequence of alternating contact with the rotating inner race and the stationary, deformed outer race, with their kinematic state being a function of position within the wave generator’s strain field.

Most significantly, the contact stress analysis confirms that both the outer ring and the rolling balls are subjected to severe, cyclical, and highly non-uniform stress fields. Stress is intensely concentrated in the major axis region, with values decaying sharply away from it. This stress concentration and the associated fluctuating contact forces are the primary drivers of fatigue failure in flexible bearings. The contact force analysis further quantifies the dynamic loading, showing that the ball-race interfaces carry the brunt of the external load with significant fluctuations due to variable compliance, while the cage plays a more stable guiding role.

The findings underscore the exceptional mechanical environment within a strain wave gear flexible bearing. The analysis methodology and results presented here form a valuable foundation for optimizing bearing geometry (e.g., raceway profiles, ball size, and count), selecting appropriate materials and heat treatments, and developing more accurate life prediction models for these critical components, ultimately enhancing the reliability and performance of strain wave gear transmission systems.