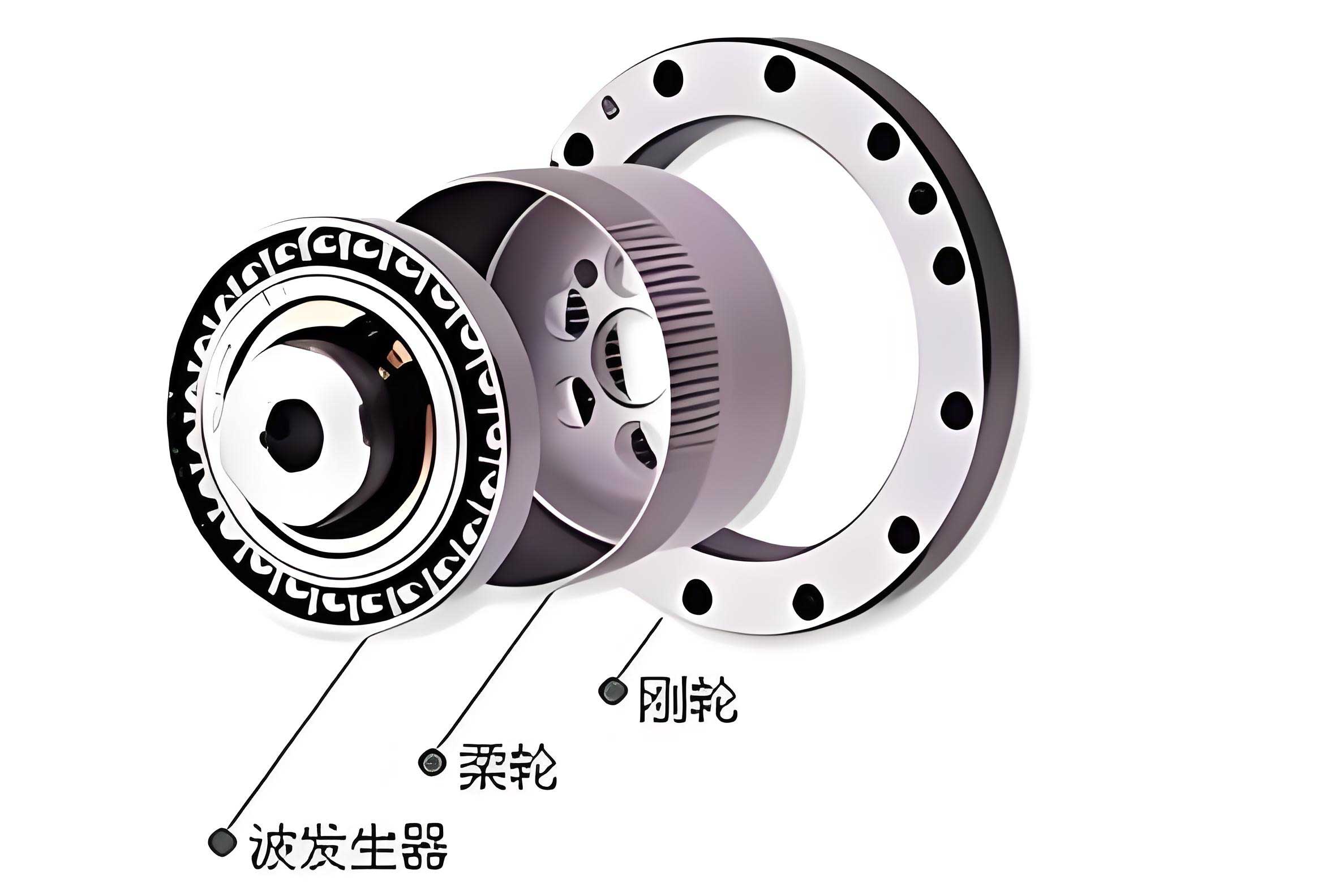

In the field of precision motion control, the strain wave gear, also known as harmonic drive, stands out due to its exceptional characteristics: compact size, light weight, high reduction ratio, and superior positional accuracy. These attributes have cemented its role as a critical component in demanding applications such as aerospace actuation systems, robotic joints, and satellite deployment mechanisms. The core of its performance lies in the unique meshing principle between a flexible spline (flexspline), a rigid circular spline, and a wave generator. Over the decades, significant research effort has been dedicated to optimizing the tooth profile of the flexspline to enhance load distribution, reduce stress concentration, minimize backlash, and ultimately improve the transmission’s longevity and stiffness. Among various profiles proposed—including involute, straight-sided, and circular arc—the double circular arc profile has shown promising results. Recently, a novel tri-arc flexspline profile has been introduced, claiming advantages over its double-arc predecessor. This article delves into a comprehensive design methodology for this tri-arc tooth profile within the strain wave gear context, employing an exact conjugate theory. A detailed parametric study investigates how the geometric parameters of the tri-arc flexspline influence the conjugate action zone, which is directly linked to the transmission’s precision and torsional rigidity.

The fundamental operation of a strain wave gear relies on the elastic deformation of the flexspline, typically a thin-walled cup, by an elliptical wave generator. This deformation causes the teeth of the flexspline to engage with those of the rigid circular spline at two diametrically opposite regions. As the wave generator rotates, these engagement zones travel, resulting in a slow relative rotation between the flexspline and the circular spline. The kinematic relationship is highly non-linear and depends critically on the assumed deformation shape of the flexspline’s neutral curve. For analytical simplicity, common assumptions are made: the system is under no-load or ideal light-load conditions, the neutral curve of the flexspline does not elongate during deformation, and it perfectly conforms to the contour of the wave generator after deformation. The tooth engagement is analyzed as a planar gear meshing problem in a cross-sectional view, considering a single tooth pair over one engagement cycle.

To establish the mathematical model, we first define the coordinate systems and the geometry of the tri-arc tooth profile. The flexspline tooth profile is composed of three tangential circular arcs: a convex arc near the tooth tip, an intermediate arc, and a concave arc near the tooth root. A tooth-fixed coordinate system \( S_1(O_1, X_1, Y_1) \) is attached to an individual flexspline tooth. The origin \( O_1 \) is located at the intersection of the tooth’s symmetry axis (the \( Y_1 \)-axis) and the neutral curve of the flexspline. The \( X_1 \)-axis is tangent to the neutral curve at \( O_1 \). The profile is defined from the tooth tip (Point A) to the root (Point D) using the arc length \( s \) as a parameter. The key geometric parameters of the tri-arc profile are illustrated below and summarized in Table 1.

The position vectors \( \mathbf{r}(s) \) and unit normal vectors \( \mathbf{n}(s) \) for each segment in homogeneous coordinates within \( S_1 \) are given as follows.

For the convex arc segment AB (\( s \in (0, l_1) \)):

$$

\mathbf{r}_{ab}(s) = \begin{bmatrix}

\rho_a \cos(\theta – s/\rho_a) + x_{oa} \\

\rho_a \sin(\theta – s/\rho_a) + y_{oa} \\

1

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

\mathbf{n}_{ab}(s) = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos(\theta – s/\rho_a) \\

\sin(\theta – s/\rho_a) \\

0

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where \( \theta = \arcsin((h_a + x_{oa})/\rho_a) \), \( y_{oa} = h – h_a + d – X_a \), and \( x_{oa} = -l_a \).

For the intermediate arc segment BC (\( s \in (l_1, l_2) \)):

$$

\mathbf{r}_{bc}(s) = \begin{bmatrix}

\rho_m \cos[\delta_1 – (s – l_1)/\rho_m] + x_{om} \\

\rho_m \sin[\delta_1 – (s – l_1)/\rho_m] + y_{om} \\

1

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

\mathbf{n}_{bc}(s) = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos[\delta_1 – (s – l_1)/\rho_m] \\

\sin[\delta_1 – (s – l_1)/\rho_m] \\

0

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where \( x_{om} = \rho_a \cos \delta_1 + x_{oa} – \rho_m \cos \delta_1 \), \( y_{om} = \rho_a \sin \delta_1 + y_{oa} – \rho_m \sin \delta_1 \), and \( l_2 = l_1 + \rho_m (\delta_1 – \delta_2) \).

For the concave arc segment CD (\( s \in (l_2, l_3) \)):

$$

\mathbf{r}_{cd}(s) = \begin{bmatrix}

x_{of} – \rho_f \cos[\delta_2 + (s – l_2)/\rho_f] \\

y_{of} – \rho_f \sin[\delta_2 + (s – l_2)/\rho_f] \\

1

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

\mathbf{n}_{cd}(s) = \begin{bmatrix}

-\cos[\delta_2 + (s – l_2)/\rho_f] \\

-\sin[\delta_2 + (s – l_2)/\rho_f] \\

0

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where \( x_{of} = \rho_m \cos \delta_2 + x_{om} + \rho_f \cos \delta_2 \), \( y_{of} = \rho_m \sin \delta_2 + y_{om} + \rho_f \sin \delta_2 \), \( l_1 = \rho_a (\theta – \delta_1) \), and \( l_3 = l_2 + \rho_f \{ \arcsin[(y_{of} – d)/\rho_f] – \delta_2 \} \).

Here, \( \rho_a, \rho_m, \rho_f \) are the radii of the convex, intermediate, and concave arcs, respectively. \( \delta_1 \) is the angle between the common tangent of the convex and intermediate arcs and the \( Y_1 \)-axis, while \( \delta_2 \) is the analogous angle for the intermediate and concave arcs. \( X_a, l_a, X_f, l_f \) are offset parameters, \( h, h_a, h_f \) are the total tooth height, addendum, and dedendum, and \( d \) is the distance from the tooth root circle to the neutral layer. The geometric relationships ensure tangency at the junction points B and C.

| Symbol | Description | Typical Value / Formula |

|---|---|---|

| \( m \) | Module | 0.32 mm |

| \( w_0^* \) | Radial deformation coefficient | 1.0 |

| \( h \) | Total tooth height | \( 1.5m \) |

| \( h_a \) | Addendum | \( 0.6m \) |

| \( h_f \) | Dedendum | \( 0.9m \) |

| \( z_R \) | Number of flexspline teeth | 160 |

| \( z_G \) | Number of circular spline teeth | 162 |

| \( \rho_a \) | Convex arc radius | Design variable (e.g., 0.62 mm) |

| \( \rho_m \) | Intermediate arc radius | Design variable (e.g., 2.7 mm) |

| \( \rho_f \) | Concave arc radius | Design variable (e.g., 0.62 mm) |

| \( \delta_1 \) | Convex-intermediate tangent angle | Design variable (e.g., 12.5°) |

| \( \delta_2 \) | Intermediate-concave tangent angle | Design variable (e.g., 10.7°) |

| \( X_a, l_a \) | Convex arc center offsets | Design variables |

| \( d \) | Root-to-neutral-layer distance | \( h_f – \text{(clearance)} \) |

The conjugate tooth profile of the rigid circular spline is derived using an exact kinematic method based on the theory of gearing. Three primary coordinate systems are defined for the strain wave gear assembly: \( S_2(O_2, X_2, Y_2) \) fixed to the circular spline, \( S(O, X, Y) \) fixed to the wave generator, and the previously defined \( S_1 \) fixed to the flexspline tooth under study. The circular spline is stationary. The wave generator, typically an elliptical cam, rotates with input angle \( \phi_2 \). The flexspline’s non-defoming end rotates by an angle \( \alpha \) relative to the circular spline, and its defoming end (the tooth ring) rotates by an angle \( \gamma \). The fundamental kinematic relationship assumes pure rolling between the circular spline’s pitch circle and the flexspline’s neutral curve in its deformed state. The transformation matrix \( \mathbf{M}_{21} \) that maps coordinates from \( S_1 \) to \( S_2 \) and the corresponding normal vector transformation matrix \( \mathbf{W}_{21} \) are crucial:

$$

\mathbf{M}_{21}(\phi_2) = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos\beta & \sin\beta & r\sin\gamma \\

-\sin\beta & \cos\beta & r\cos\gamma \\

0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

\mathbf{W}_{21}(\phi_2) = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos\beta & \sin\beta & 0 \\

-\sin\beta & \cos\beta & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where \( \beta = \alpha + \gamma – \mu \), \( r \) is the distance from the wave generator center to the point \( O_1 \) on the deformed neutral curve, and \( \mu \) is the angle of the vector \( \overrightarrow{OO_1} \). All angles are functions of the input rotation \( \phi_2 \) and the specific deformation function of the flexspline (e.g., an elliptical shape given by \( r = r_0 + w_0 \cos(2\phi_1) \), where \( r_0 \) is the nominal radius and \( w_0 \) is the major radial deformation).

The condition for conjugate contact (the equation of meshing) at any instant is that the relative velocity vector at the contact point is orthogonal to the common surface normal. For the two gears, this condition in coordinate system \( S_i \) is expressed as:

$$

\mathbf{n}^{(i)} \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)(i)} = 0, \quad (i=1,2)

$$

where \( \mathbf{n}^{(i)} \) is the unit normal vector of the tooth surface in system \( S_i \), and \( \mathbf{v}^{(12)(i)} \) is the relative velocity vector of the two surfaces in that system. Using the transformations, we have \( \mathbf{n}^{(2)} = \mathbf{W}_{21} \mathbf{n}^{(1)} \) and \( \mathbf{v}^{(12)(2)} = \frac{d\mathbf{r}^{(2)}}{dt} = \frac{d\mathbf{M}_{21}}{dt} \mathbf{r}^{(1)} \). Substituting the profile equations \( \mathbf{r}^{(1)}(s) \) and \( \mathbf{n}^{(1)}(s) \) into these relationships and enforcing the meshing condition yields a scalar equation linking the profile parameter \( s \) and the input angle \( \phi_2 \):

$$

F(s, \phi_2) = 0.

$$

Solving this equation for a given \( \phi_2 \) provides the specific point \( s \) on the flexspline profile that is in conjugate contact at that instant. The set of all solutions \( (\phi_2, s) \) defines the conjugate zone—the range of input rotation where true theoretical line contact occurs for that tooth pair. In practice, for strain wave gears, a single flexspline tooth typically experiences two separate conjugate engagement periods (double conjugate action) during one full cycle of the wave generator. The interval between these two conjugate zones is where only point contact or “tip” contact occurs, which is less desirable for load distribution and stiffness.

To illustrate and compare the performance, a computational case study is performed. The base parameters are chosen as per Table 1: module \( m=0.32 \text{ mm} \), radial deformation coefficient \( w_0^* = 1.0 \), tooth counts \( z_R=160 \), \( z_G=162 \). For the tri-arc profile, specific initial design parameters might be: \( \rho_a = 0.62 \text{ mm} \), \( \rho_m = 2.7 \text{ mm} \), \( \rho_f = 0.62 \text{ mm} \), \( \delta_1 = 12.5^\circ \), \( \delta_2 = 10.7^\circ \), with appropriate offsets \( X_a, l_a \) determined from geometric constraints. For comparison, a classic double circular arc (tangent type) profile is also analyzed with its typical parameters, where the profile consists of only a convex arc and a concave arc connected by a common tangent, eliminating the intermediate arc.

The conjugate zones calculated for both profiles are presented in Table 2. The input angle \( \phi_2 \) is measured in degrees relative to an initial position. The conjugate zone is defined by the start and end angles of the first and second conjugate engagement periods for a representative flexspline tooth.

| Tooth Profile Type | First Conjugate Zone \( [\phi_{2,\text{start}}^1, \phi_{2,\text{end}}^1] \) (°) | Second Conjugate Zone \( [\phi_{2,\text{start}}^2, \phi_{2,\text{end}}^2] \) (°) | Conjugate Interval (Gap) (°) | Total Conjugate Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double Circular Arc | [2.90405, 9.17592] | [14.25278, 45.70194] | 9.17592 to 14.25278 (≈5.07686) | ≈38.52209 |

| Tri-Arc | [2.90405, 10.34781] | [10.86511, 45.70194] | 10.34781 to 10.86511 (≈0.51730) | ≈42.88479 |

The results clearly demonstrate the advantage of the tri-arc profile in the context of strain wave gear design. The tri-arc profile significantly expands both the first and second conjugate zones. More importantly, it drastically reduces the non-conjugate interval (the gap) from over 5 degrees to just about 0.52 degrees. This implies that for a larger portion of the wave generator’s rotation cycle, the tooth pair maintains theoretical line contact, leading to more teeth being in simultaneous conjugate engagement. This characteristic is highly beneficial for improving the torsional stiffness and positional accuracy of the strain wave gear transmission, as it reduces the reliance on less stable point contacts.

The theoretical conjugate profiles of the circular spline corresponding to each segment of the tri-arc flexspline can be calculated. However, not all theoretically conjugate segments are practically usable due to potential interference during the meshing cycle. Typically, the practical circular spline profile is synthesized from the first conjugate profile of the convex arc, the first conjugate profile of the intermediate arc, and the second conjugate profile of the convex arc. The concave arc segment of the flexspline generally does not participate in functional conjugate contact during the standard engagement, as its conjugate action occurs outside the practical motion range or would cause interference.

A critical aspect of designing an optimal strain wave gear is understanding the sensitivity of performance metrics to the geometric parameters of the tooth profile. We therefore conduct a parametric analysis on the tri-arc profile, focusing on how variations in \( \rho_a \), \( \rho_m \), \( \rho_f \), \( \delta_1 \), and \( \delta_2 \) influence the conjugate zone characteristics. The base parameters from the previous case are used, and one parameter is varied at a time while others are held constant. The effects are quantified in terms of changes in the start and end angles of the conjugate zones and the length of the conjugate interval. The trends are summarized in Table 3 and discussed below.

| Parameter | Trend of Increase | Effect on 1st Conjugate Zone | Effect on 2nd Conjugate Zone | Effect on Conjugate Interval (Gap) | Overall Impact on Total Conjugate Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convex Arc Radius \( \rho_a \) | Increase | Very slight decrease (end angle) | Significant decrease (start angle increases) | Slight decrease | Reduces total conjugate zone substantially. |

| Intermediate Arc Radius \( \rho_m \) | Increase | Significant decrease | Significant decrease (start angle increases) | Increases | Reduces total conjugate zone and widens the gap, detrimental. |

| Concave Arc Radius \( \rho_f \) | Increase | Negligible change for functional arcs* | Changes only for non-functional concave arc engagement. | No practical effect | Minimal impact on actual meshing performance. |

| Angle \( \delta_1 \) | Increase | Significant decrease | Significant decrease (start angle increases) | Increases | Reduces total conjugate zone and widens the gap, detrimental. |

| Angle \( \delta_2 \) | Increase | No change for convex arc; decreases for intermediate arc segment. | No change for convex arc; decreases intermediate arc contribution. | Increases | Reduces the conjugate zone contribution from the intermediate arc and widens the gap. |

* The concave arc’s own conjugate zones are not part of the practical meshing cycle due to interference.

The influence of the convex arc radius \( \rho_a \) is primarily on the second conjugate zone. A smaller \( \rho_a \) tends to advance the start of the second conjugate zone (\( \phi_{2,\text{start}}^2 \) becomes smaller), thereby extending the total conjugate zone. However, its effect on shrinking the conjugate interval is minimal. The intermediate arc parameters \( \rho_m \) and \( \delta_1 \) have a strong and similar influence. Increasing either \( \rho_m \) or \( \delta_1 \) significantly shrinks both conjugate zones and, critically, widens the non-conjugate interval. This is undesirable. Therefore, to maximize the conjugate action and minimize the gap in a strain wave gear, designers should aim for smaller values of \( \rho_m \) and \( \delta_1 \), within manufacturing and strength constraints. The angle \( \delta_2 \) mainly affects the portion of conjugate action contributed by the intermediate arc segment. A larger \( \delta_2 \) reduces this contribution and also increases the gap. Hence, a smaller \( \delta_2 \) is preferable. The concave arc radius \( \rho_f \) has negligible influence on the practically used conjugate zones originating from the convex and intermediate arcs. Its theoretical conjugate action is often irrelevant because it would lead to interference with other parts of the meshing cycle. Thus, \( \rho_f \) can be chosen primarily based on root fillet and stress concentration considerations rather than conjugate performance.

These parametric trends can be further visualized and quantified through systematic equations. For instance, the relationship between the conjugate condition and the profile parameter \( s \) can be approximated for sensitivity analysis. The meshing condition \( F(s, \phi_2)=0 \) can be differentiated implicitly to examine how changes in a geometric parameter \( p \) (e.g., \( \rho_a \)) affect the critical angles \( \phi_2 \).

$$

\frac{\partial F}{\partial s} ds + \frac{\partial F}{\partial \phi_2} d\phi_2 + \frac{\partial F}{\partial p} dp = 0.

$$

At the boundaries of the conjugate zones, specific conditions often hold (e.g., contact at the endpoints of the arc segments), allowing for analytical insights. For example, the end of the first conjugate zone for the convex arc might correspond to the point where contact leaves the convex arc and transitions to the intermediate arc. This transition condition is sensitive to \( \delta_1 \) and \( \rho_m \).

The benefits of a widened conjugate zone and a minimized non-conjugate interval in a strain wave gear are multifaceted. Firstly, it increases the number of tooth pairs that are in theoretically ideal contact at any given input angle. This leads to a more uniform load distribution across the teeth, reducing peak contact stresses and the risk of pitting or wear. Secondly, the transmission error, which is a critical measure of precision, is minimized because the motion transfer relies more on deterministic conjugate action and less on ambiguous contact points that can vary with load or manufacturing tolerances. Thirdly, the torsional stiffness of the strain wave gear assembly is enhanced. When teeth are in line contact (conjugate condition), they resist torsional deflection more effectively than when in point contact. A smaller conjugate interval means the stiffness dip associated with the transition period is reduced, leading to a more consistent and higher overall stiffness throughout the rotation. This is particularly important for servo applications in robotics and aerospace where high stiffness and low backlash are paramount.

In conclusion, the tri-arc tooth profile presents a significant advancement in the design of high-performance strain wave gears. By introducing an intermediate circular arc between the traditional convex and concave arcs, the engagement characteristics are markedly improved. The comprehensive design methodology, rooted in exact conjugate theory, allows for precise determination of the circular spline profile and analysis of the conjugate zones. The parametric study unequivocally shows that careful selection of the tri-arc parameters—specifically, using smaller convex arc radii, significantly smaller intermediate arc radii, and smaller angles \( \delta_1 \) and \( \delta_2 \)—can yield a strain wave gear with a substantially expanded total conjugate zone and a dramatically reduced non-conjugate interval. This design strategy effectively promotes conjugate line contact over a greater portion of the engagement cycle, reducing tip contact and its associated drawbacks. Consequently, adopting the optimized tri-arc profile can lead to strain wave gear transmissions with superior accuracy, higher torsional stiffness, and potentially longer operational life, meeting the ever-increasing demands of precision engineering applications. Future work may involve multi-objective optimization incorporating stress constraints, thermal effects, and detailed lubrication analysis for these advanced strain wave gear tooth profiles.