The pursuit of high-performance actuation in aerospace applications, such as missile guidance systems and robotic manipulators, demands transmission components that offer exceptional precision, compactness, and reliability. Among available technologies, strain wave gear drives, also commonly known as harmonic drives, have proven uniquely suited for these demanding roles. Their distinguishing advantages include high single-stage reduction ratios, near-zero backlash, high positional accuracy, and commendable torque-to-weight ratios. However, the very mechanism that grants the strain wave gear its superior characteristics—the controlled elastic deformation of its flexspline—introduces complex nonlinear dynamic behaviors. These nonlinearities, stemming from time-varying mesh stiffness, hysteresis losses, and the unavoidable presence of minute backlash, can significantly influence the performance metrics critical to closed-loop control systems: stability margins, tracking accuracy, phase lag, and transient response.

Traditional linear models often fall short in accurately predicting the dynamic response of a strain wave gear assembly under real-world operating conditions. Therefore, a comprehensive nonlinear dynamic analysis is not merely an academic exercise but an engineering necessity for optimizing system design and diagnosing operational issues. This article delves into the development of a nonlinear dynamic model for a strain wave gear transmission, its implementation in a simulation environment, and a detailed parametric study. The influence of key physical parameters such as viscous damping, gear tooth backlash, and torsional stiffness on system performance, particularly phase shift, is rigorously investigated. Furthermore, the correlation between simulation predictions and empirical test data is examined to validate the model and provide practical insights for design improvement.

Fundamental Working Principle and Nonlinear Characteristics

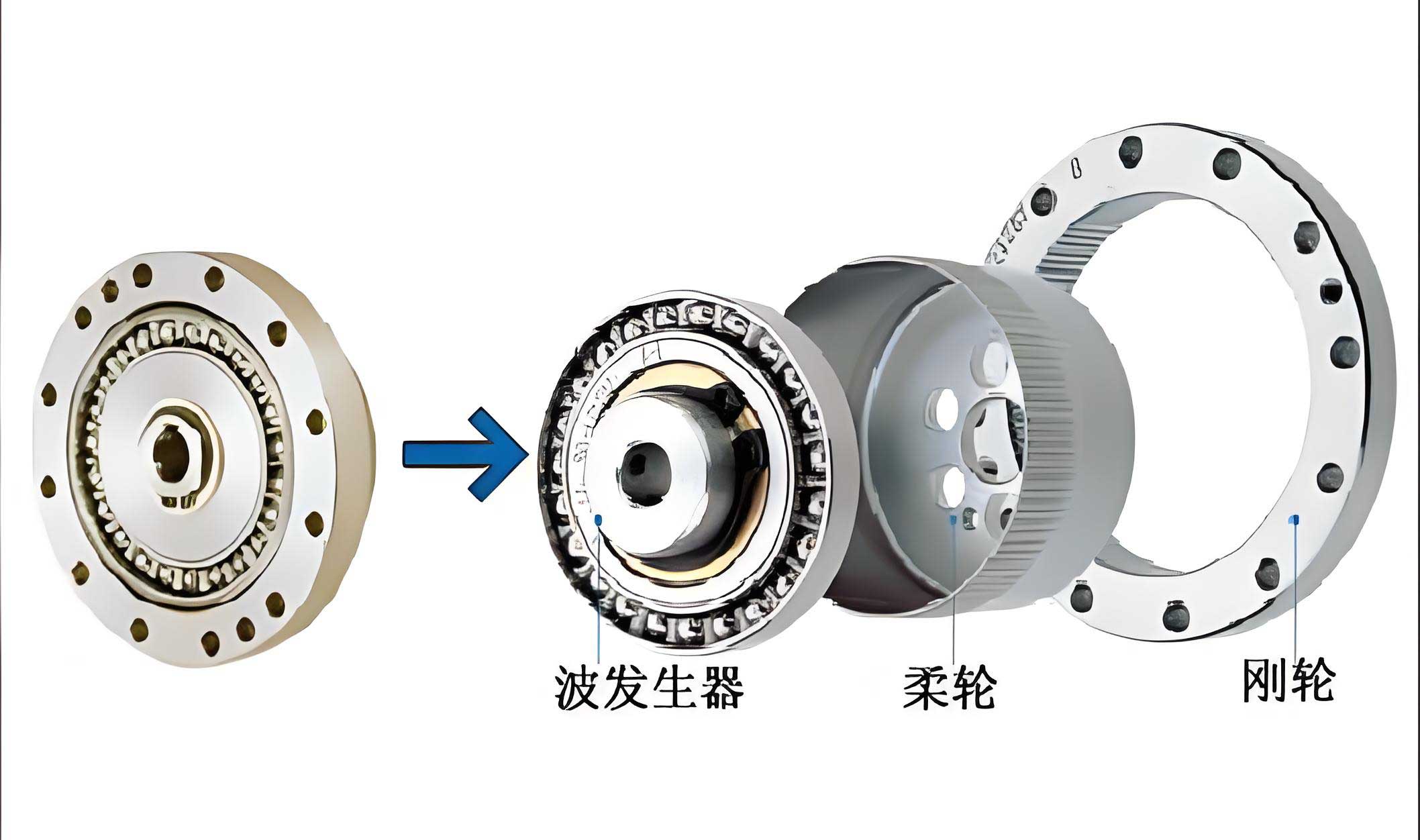

At its core, a strain wave gear operates on the principle of elastic kinematics. It comprises three primary elements: a rigid Circular Spline (CS), a flexible Flexspline (FS), and an elliptical or cam-type Wave Generator (WG). The WG, inserted into the FS, forces it into an elliptical shape, causing its external teeth to engage with the internal teeth of the CS at two diametrically opposite regions. As the WG rotates, the engagement zones travel, resulting in a relative motion between the FS and CS. The speed reduction ratio is determined by the difference in the number of teeth between the FS and the CS: \( i = – \frac{Z_{FS}}{Z_{CS} – Z_{FS}} \), where \( Z_{FS} \) and \( Z_{CS} \) are the number of teeth on the flexspline and circular spline, respectively.

The nonlinear dynamic behavior of a strain wave gear arises from several sources:

- Nonlinear Stiffness: The torsional stiffness is not constant. The periodic engagement/disengagement of teeth and the elastic deformation of the FS lead to a stiffness that varies with the angular position of the WG. Furthermore, the load-deflection curve exhibits a hysteresis loop due to internal friction and material damping within the flexing metal, making the restoring torque a function of both displacement and the history of motion.

- Backlash: Despite being minimal, a residual clearance or tooth flank backlash exists between mating teeth. This discontinuity causes a dead-zone in the torque transmission, a classic nonlinearity that can induce limit cycles, tracking errors, and instability.

- Friction: The system exhibits both viscous (speed-dependent) and Coulomb (constant-torque) friction components at bearings, seals, and the meshing interface. These dissipative forces are nonlinear and significantly affect efficiency and damping.

Mathematical Formulation of the Nonlinear Dynamic Model

To capture these effects, a lumped-parameter model is developed. The system is reduced to two primary inertias: the combined inertia of the motor rotor and the wave generator (\(J_m\)), and the load inertia (\(J_l\)). The elasticity and backlash of the strain wave gear assembly are aggregated into a single nonlinear element connecting these two inertias. The model is referred to the output side for analysis convenience. The equivalent inertia on the input (motor) side, when reflected to the output shaft, is \( J_i = J_m / i^2 \), where \( i \) is the gear ratio. The input displacement reflected to the output is \( \theta_i(t) = \theta_m(t) / i \).

The central element of the model is the description of the nonlinear elastic torque \( T_g(t) \) transmitted through the gear. This torque depends on the effective elastic deformation \( \Delta_e(t) \), which must account for the total backlash \( 2\beta \).

1. Backlash Nonlinearity Function:

The elastic deformation is defined as the difference between the reflected input angle and the output angle, processed through a dead-zone function representing backlash:

$$ \Delta_e(t) = B(\theta_i(t) – \theta_o(t), \beta) = \begin{cases}

\theta_i(t) – \theta_o(t) – \beta, & \text{if } \theta_i(t) – \theta_o(t) > \beta \\

0, & \text{if } |\theta_i(t) – \theta_o(t)| \le \beta \\

\theta_i(t) – \theta_o(t) + \beta, & \text{if } \theta_i(t) – \theta_o(t) < -\beta

\end{cases} $$

Here, \( \theta_o(t) \) is the output angular displacement and \( \beta \) is half the total angular backlash.

2. Transmission Torque Model:

The transmitted torque \( T_g(t) \) is modeled as a function of this elastic deformation and its rate of change. A simplified yet effective representation combines a linear stiffness term with a viscous damping term representing internal losses:

$$ T_g(t) = K \cdot \Delta_e(t) + C \cdot \frac{d}{dt}\Delta_e(t) $$

Where \( K \) is the equivalent nonlinear stiffness coefficient (which could be modeled as a polynomial or piecewise function for higher fidelity) and \( C \) is an equivalent viscous damping coefficient for the gear mesh. In a more advanced model, \( K \) could be replaced by a hysteresis operator.

3. System Equations of Motion:

Applying Newton’s second law to the input-side and output-side inertias, the coupled differential equations are:

$$ T_i(t) – T_g(t) – f_i \dot{\theta}_i – c_i \theta_i = J_i \ddot{\theta}_i $$

$$ T_g(t) – T_l(t) – f_o \dot{\theta}_o – c_o \theta_o = J_o \ddot{\theta}_o $$

Where:

- \( T_i(t) \): Reflected input torque (motor torque / i).

- \( T_l(t) \): External load torque.

- \( f_i, f_o \): Viscous friction coefficients on input and output sides.

- \( c_i, c_o \): Static imbalance or linear drag coefficients (often small).

- \( J_o \): Load inertia.

The nonlinear coupling is embedded within \( T_g(t) \) through \( \Delta_e(t) \).

Simulation Model Development and Parametric Analysis

The mathematical model is implemented in MATLAB/Simulink, a platform well-suited for simulating nonlinear dynamic systems. The block diagram model incorporates the following key components:

- Input Source Blocks: Generating reference signals (step, sinusoidal) for motor command.

- Motor/Controller Model: A simplified model representing the servo motor’s torque generation in response to input.

- Nonlinear Gear Subsystem: This core block encapsulates the backlash function \( B(\cdot) \) and the transmission torque calculation \( T_g = K \cdot \Delta_e + C \cdot \dot{\Delta_e} \).

- Inertia and Damping Blocks: Representing \( J_i, J_o, f_i, f_o \).

- Scopes and Data Logging: To capture time-domain responses of input vs. output angle, transmitted torque, and phase difference.

The simulation is performed on a model representing a high-performance strain wave gear with the following nominal parameters, typical for aerospace servo applications:

$$ i = 80, \quad J_i = 2.2 \times 10^{-4} \, \text{kg·m}^2, \quad J_o = 0.284 \, \text{kg·m}^2, \quad K = 1 \times 10^4 \, \text{Nm/rad}, \quad f_i = f_o = 0.01 \, \text{Nm·s/rad}, \quad 2\beta = 8′ \, (\text{approx. } 2.32 \times 10^{-3} \, \text{rad}) $$

The analysis focuses on quantifying the impact of three critical parameters: viscous damping coefficient (\(f\)), backlash (\(2\beta\)), and stiffness (\(K\)). Performance is evaluated through the system’s response to sinusoidal inputs (to measure phase lag and waveform distortion) and step inputs (to assess settling time and overshoot).

1. Influence of Viscous Damping Coefficient

Viscous damping, arising from lubricant shearing and internal friction, is a primary source of energy dissipation. Simulations were run with damping coefficients varied over an order of magnitude. The phase lag between input and output under sinusoidal excitation and the step response were analyzed.

Observations:

- Stability vs. Responsiveness Trade-off: Higher damping (\(f\) increased by 5x) significantly improves stability, virtually eliminating oscillations in the step response. However, this comes at the cost of increased phase lag in the frequency response and a longer settling time. The system becomes more sluggish.

- Amplitude and Efficiency: The amplitude of the output for a given input torque decreases with higher damping, indicating lower transmission efficiency, as more energy is dissipated as heat.

- Mechanism: The damping term \( f \dot{\theta} \) acts as a stabilizing force opposing velocity, which suppresses oscillations but also retards motion.

Design Implication: For a strain wave gear in a high-bandwidth servo system, damping must be minimized to preserve quick response and low phase lag, but not eliminated entirely to ensure adequate stability margins. Lubricant selection is critical here.

| Parameter Change | Phase Lag (Sinusoidal) | Step Response Overshoot | Settling Time | System Character |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Damping (0.5×f_nom) | Minimal | High | Long (oscillatory) | Fast, Underdamped |

| Nominal Damping (f_nom) | Moderate | Acceptable | Moderate | Well-balanced |

| High Damping (5×f_nom) | Significantly Increased | None | Long (sluggish) | Stable, Overdamped |

2. Influence of Gear Tooth Backlash

Backlash, the angular free play between mated components, is a severe nonlinearity. Its effect was simulated by varying \( 2\beta \) from near-zero to a perceptible clearance.

Observations:

- Dead Zone and Tracking Error: The primary effect is a dead zone in the transmission. For small command signals that do not overcome the backlash, no output motion occurs, leading to static positioning error.

- Limit Cycles and Vibration: In dynamic operation, especially under reversal of motion, backlash causes a momentary loss of contact, leading to an impact when contact is re-established. This can induce persistent, low-amplitude limit cycle oscillations in the output, even when the input is steady. This self-excited vibration degrades stability and precision.

- Phase Distortion and Waveform Fidelity: The sinusoidal response waveform shows flattening or distortion near the zero-crossing points due to the dead zone, and the effective phase lag increases irregularly.

Design Implication: Minimizing backlash is paramount for precision in strain wave gear applications. This requires meticulous control of manufacturing tolerances, tooth profile design, and assembly preload. While some minimal clearance is necessary for lubrication, the goal is to reduce it to a level negligible for the control system’s sensitivity threshold.

| Backlash Level | Static Error | Dynamic Stability | Output Waveform | Key Issue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negligible (≈0) | None | Excellent | Clean, sinusoidal | Ideal, difficult to achieve |

| Low (Nominal) | Small | Good, minor vibration | Slight distortion at zero-crossing | Acceptable for many apps |

| High (2×Nominal) | Significant | Poor, clear limit cycles | Severe distortion, flat spots | Unacceptable for servo control |

3. Influence of Torsional Stiffness

The equivalent torsional stiffness \( K \) of the strain wave gear transmission is a dominant factor in determining the system’s natural frequency. Its value was varied in the simulation to assess the impact.

Observations:

- Natural Frequency and Bandwidth: A higher stiffness directly increases the natural frequency of the mechanical resonance (\( \omega_n \propto \sqrt{K/J} \)). This pushes the resonant peak in the frequency response to a higher frequency, effectively widening the system’s usable control bandwidth.

- Phase Lag Reduction: At a given operating frequency, a stiffer system exhibits less phase lag due to the reduced compliance. The phase margin of the control loop improves.

- Torque Ripple Transmission: While beneficial for bandwidth, higher stiffness can also mean less attenuation of high-frequency torque ripple from the motor or load disturbances.

Design Implication: Maximizing the torsional stiffness of the strain wave gear assembly is highly beneficial for dynamic performance. The stiffness is often dominated by the output shaft and the flexspline’s radial compliance. Therefore, design efforts should focus on reinforcing the output shaft and optimizing the flexspline’s wall thickness and material properties without compromising its necessary flexibility for the wave-generating motion.

The relationship between the natural frequency \( \omega_n \), stiffness \( K \), and inertia \( J_{eq} \) (the equivalent inertia of the system) is given by:

$$ \omega_n = \sqrt{\frac{K}{J_{eq}}} $$

where \( J_{eq} \) is a combination of \( J_i \) and \( J_o \). A 4x increase in \( K \) yields a 2x increase in \( \omega_n \), dramatically improving the dynamic response.

Case Study: Correlation with Experimental Data and Problem Resolution

The validity of the nonlinear simulation model was tested against empirical data from a strain wave gear used in a developmental aerospace project. Dynamic performance tests were conducted by driving the gear with a sinusoidal input and measuring the output under varying environmental temperatures.

The Observed Anomaly: While the gear performed excellently at room temperature and elevated temperatures (+70°C), showing minimal phase lag and clean waveforms, a severe performance degradation was recorded at low temperature (-40°C). The symptoms included a substantial increase in phase lag, a noticeable drop in output amplitude (indicating loss of efficiency), and a generally “stiff” response.

Analysis Using the Model Framework: Initial hypotheses focused on potential structural changes (e.g., material embrittlement). However, finite element analysis ruled out significant alterations in component stiffness or natural frequencies. The simulation-based parametric study pointed towards a change in the viscous damping parameter as the most likely culprit. The primary variable affecting this parameter in the assembly is the lubricating grease.

Lubricant Investigation: The gear was originally lubricated with a general-purpose aerospace grease (Grease A) with a broad operational temperature range. An examination of its properties revealed that while it remained functional at -40°C, its base oil viscosity increased dramatically at low temperatures. This high viscosity would lead to a significant increase in the viscous damping coefficients (\(f_i, f_o, C\)) within the strain wave gear model.

Simulation vs. Experiment Correlation: The simulation model was reconfigured with damping values calibrated to represent the high-viscosity condition. The simulated output closely matched the experimental data from the low-temperature test: increased phase lag and reduced amplitude. Subsequently, a test was performed using a specialized low-temperature grease (Grease B) formulated with a synthetic base oil maintaining a much lower viscosity at -40°C.

| Lubricant | Base Oil Viscosity at -40°C | Simulated Damping Coeff. (Relative) | Experimental Phase Lag at -40°C | System Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grease A (Original) | Very High (~1100 mPa·s) | High (5× nominal) | Large (> 15°) | Poor, sluggish, inefficient |

| Grease B (Low-temp) | Low (~300 mPa·s) | Near Nominal (1.2×) | Small (< 5°) | Good, responsive, efficient |

The experimental results with Grease B showed a dramatic recovery of performance, with phase lag and amplitude returning to near room-temperature levels. This confirmed that the increased viscous damping due to improper lubricant selection was the root cause. The case perfectly validated the simulation’s prediction regarding the sensitivity of strain wave gear dynamic performance to the damping parameter.

Conclusions and Design Guidelines

This nonlinear dynamic analysis of a strain wave gear transmission system provides a framework for understanding and optimizing its performance in high-precision servo applications. The key conclusions are:

- Model Fidelity: A nonlinear model incorporating backlash and a stiffness/damping representation is essential for accurate dynamic performance prediction, especially when investigating stability, phase lag, and transient response.

- Parameter Sensitivity: The system exhibits strong sensitivity to three key parameters:

- Viscous Damping: Must be carefully optimized. Too little causes instability; too much degrades bandwidth and efficiency. Lubricant selection is a critical design decision.

- Backlash: Must be minimized to the greatest extent possible through precision manufacturing and assembly to avoid dead zones, limit cycles, and tracking errors.

- Torsional Stiffness: Should be maximized, primarily by designing a robust output shaft and an optimally stiff flexspline, to raise the natural frequency and improve phase response.

- Practical Validation: The correlation between simulation and experiment in the low-temperature case study demonstrates the model’s practical utility for diagnostic problem-solving and design validation.

Recommended Design Practices for High-Performance Strain Wave Gear Systems:

- Select lubricants based on their viscosity-temperature profile for the entire operational envelope, prioritizing low viscous drag for servo applications.

- Implement stringent tolerance control and consider slight pre-loading (where applicable) to functionally eliminate backlash.

- Conduct a stiffness analysis of the entire transmission path, focusing on the output stage. Use high-strength materials and optimal geometries.

- In high-performance systems, consider placing an additional, small-ratio precision gear stage between the motor and the strain wave gear input. This reduces the inertia reflected to the motor, can further attenuate high-frequency errors, and allows the strain wave gear to operate at a more optimal speed.

Future Work: The presented model can be enhanced by incorporating a more sophisticated representation of the stiffness hysteresis loop and distributed frictional effects. Furthermore, integrating this nonlinear gear model with a complete electro-mechanical servo actuator model, including motor dynamics and controller algorithms, would enable full system-level optimization for specific aerospace guidance and control tasks.