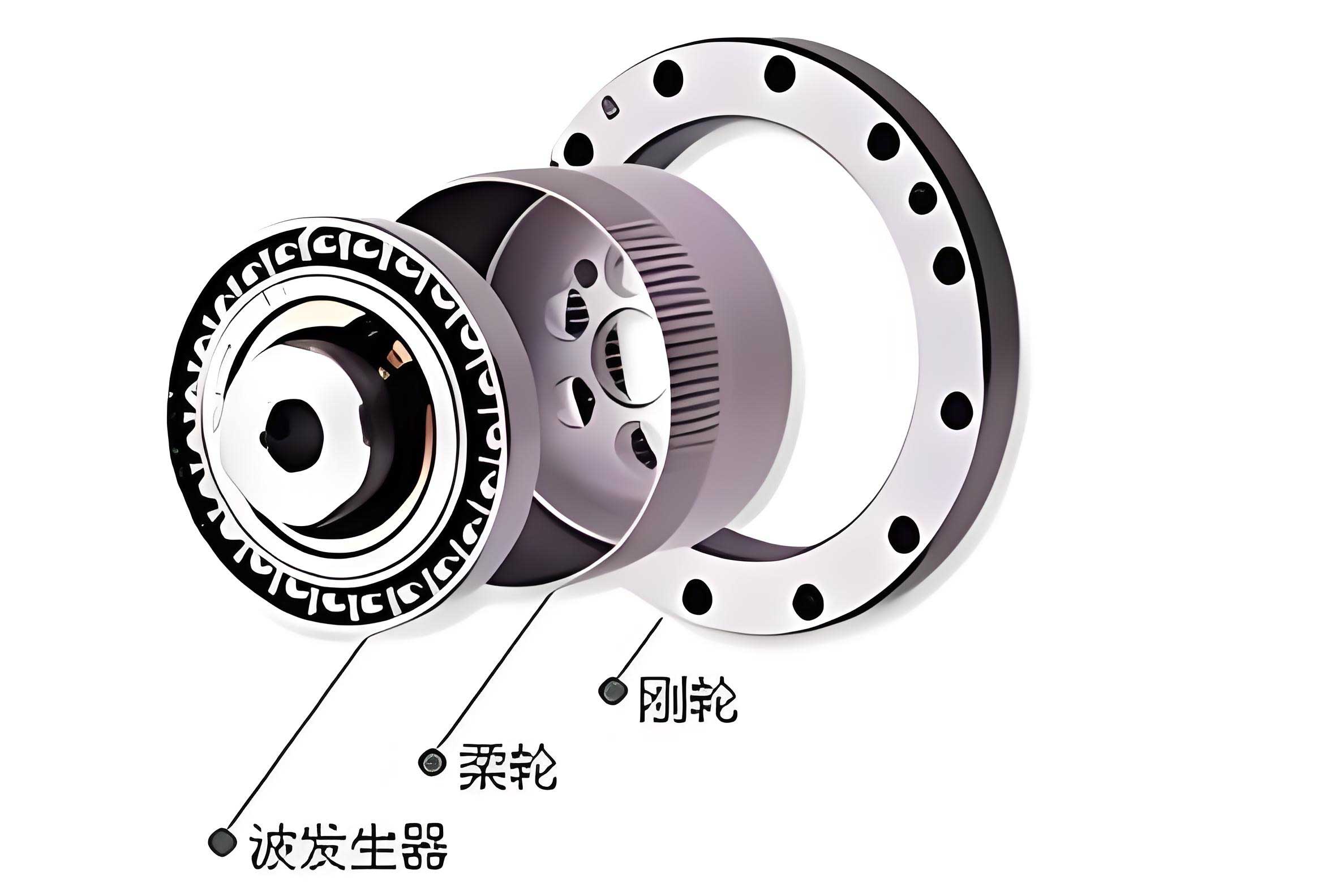

The design of the tooth profile is a fundamental aspect influencing the performance, reliability, and longevity of strain wave gears. Conventional profile design methodologies often rely on planar kinematic analysis, assuming that the deformation of the thin-walled flexspline is consistent across its entire tooth width. However, in a practical assembly, the flexspline undergoes a complex, three-dimensional spatial deformation. This deformation varies along the axial direction due to the boundary conditions imposed by the wave generator at one end and the connection to the output hub at the other. Ignoring this spatial deformation can lead to significant discrepancies between the theoretical and actual meshing conditions. A primary consequence is tooth profile interference, particularly at the ends of the tooth width, which induces elevated contact stresses, accelerates wear, increases frictional losses, and can ultimately lead to premature failure of the strain wave gear.

This article presents a novel, comprehensive design methodology for a double-circular-arc tooth profile that explicitly accounts for the spatial deformation of the flexspline. The core of this method is an extension of the bidirectional conjugate principle into the spatial domain. By performing conjugate calculations on distinct cross-sections of the flexspline tooth that experience different magnitudes of deformation, a tooth profile pair for the circular spline and flexspline is derived that maintains proper meshing contact and avoids interference under real-world deformed conditions. The validity of the theoretical spatial deformation model and the effectiveness of the proposed design approach are rigorously demonstrated through three-dimensional finite element analysis (FEA) of the complete strain wave gear assembly under both assembly and loaded conditions.

Analysis of Spatial Deformation in the Flexspline

The flexspline, a key component in the strain wave gear, is essentially a thin-walled cylindrical shell. Its deformation under the action of the wave generator is not uniform along its axis. A fundamental understanding of this deformation is crucial for accurate tooth profile design. The deformation can be analyzed using the semi-membrane theory for cylindrical shells. Under the assumption that the generator line of the cylindrical shell remains straight after deformation (a valid approximation for typical flexspline geometries), the radial deformation at any axial location can be modeled as varying linearly from the fixed end (the diaphragm or cup bottom) to the open end where the wave generator acts.

Let \( z \) define the axial coordinate measured from the fixed end (cup bottom) of the flexspline, and \( L_v \) be the axial distance from the fixed end to the main cross-section, typically located at the center of the wave generator’s bearing. The radial deformation \( \omega_z \) at an axial position \( z \) is related to the radial deformation \( \omega(\phi) \) at the main cross-section (where \( z = L_v \)) by the linear relationship:

$$

\omega_z(\phi) = \frac{z}{L_v} \omega(\phi)

$$

where \( \phi \) is the angular coordinate. At the main cross-section, the radial deformation \( \omega(\phi) \) is primarily dictated by the contour of the wave generator. For a standard elliptical wave generator, this is often approximated as \( \omega(\phi) = \omega_0 \cos(2\phi) \), where \( \omega_0 \) is the maximum radial deformation at the major axis.

A critical parameter arising from this spatial deformation is the conical deflection angle \( \theta_c \), which represents the tilt of the flexspline’s neutral surface at the major axis. It is derived from the maximum deformation:

$$

\theta_c = \arctan\left(\frac{\omega_0}{L_v}\right)

$$

This axial variation in deformation directly impacts the meshing geometry of the teeth. Consider three characteristic cross-sections along the tooth width \( b_R \): the Front Section (closest to the open end), the Central Section (aligned with the wave generator’s main cross-section), and the Back Section (closest to the fixed end). The distances from the central section to the front and back sections are denoted as \( l_2 \) and \( l_1 \), respectively.

The radial deformations at the front (\( \omega_f \)) and back (\( \omega_b \)) sections, relative to the central section deformation \( \omega(\phi) \), are given by:

$$

\omega_f(\phi) = \left(1 + \frac{l_2}{\omega_0} \tan \theta_c\right) \omega(\phi) = \left(1 + \frac{l_2}{L_v}\right) \omega(\phi)

$$

$$

\omega_b(\phi) = \left(1 – \frac{l_1}{\omega_0} \tan \theta_c\right) \omega(\phi) = \left(1 – \frac{l_1}{L_v}\right) \omega(\phi)

$$

For a tooth with its central section at the wave generator’s main cross-section, \( l_1 = l_2 = b_R/2 \). The key insight is that the deformation amplitude is larger at the front section and smaller at the back section compared to the central section. This difference can be significant, often exceeding 10% for typical strain wave gear dimensions. This “tooth tilting” effect means that a tooth profile perfectly conjugate in the central plane will be mismatched at the front and back sections, potentially leading to edge contact or interference.

The following table summarizes the deformation parameters for a representative strain wave gear:

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth Width | \( b_R \) | 10 mm | Axial length of the flexspline tooth. |

| Front/Central Distance | \( l_2 \) | 5 mm | Distance from central to front section. |

| Back/Central Distance | \( l_1 \) | 5 mm | Distance from central to back section. |

| Central to Fixed End | \( L_v \) | 43 mm | Axial length from main section to cup bottom. |

| Max. Radial Deformation (Central) | \( \omega_0 \) | 0.25 mm | Radial deflection at major axis, central section. |

| Conical Deflection Angle | \( \theta_c \) | 0.005814 rad | Calculated tilt angle of the neutral surface. |

| Max. Radial Deformation (Front) | \( \omega_{f0} \) | 0.2791 mm | Radial deflection at major axis, front section. |

| Max. Radial Deformation (Back) | \( \omega_{b0} \) | 0.2209 mm | Radial deflection at major axis, back section. |

| Deformation Error (Front) | – | +11.64% | Percentage increase relative to central section. |

| Deformation Error (Back) | – | -11.64% | Percentage decrease relative to central section. |

The mathematical expressions for the deformation at the front and back sections become:

$$

\omega_f(\phi) = (\omega_0 + l_2 \tan \theta_c) \cos(2\phi) = \omega_{f0} \cos(2\phi)

$$

$$

\omega_b(\phi) = (\omega_0 – l_1 \tan \theta_c) \cos(2\phi) = \omega_{b0} \cos(2\phi)

$$

This analysis clearly shows that the effective operating geometry of the strain wave gear differs substantially between the front and back of the tooth. A design based solely on the central section will therefore be suboptimal and prone to the aforementioned issues.

Spatial Bidirectional Conjugate Design Methodology

To overcome the limitations of planar design, a spatial bidirectional conjugate method is proposed. This method systematically incorporates the spatially-varying deformation of the flexspline into the conjugate generation of the double-circular-arc tooth profiles for both the flexspline and the circular spline.

The fundamental principle of the bidirectional conjugate method is to generate the circular spline profile from a predefined flexspline convex arc, and then to generate the flexspline concave arc from the newly generated circular spline convex arc. The spatial adaptation involves selecting the appropriate deformed flexspline cross-section for each conjugate calculation step to ensure non-interference across the entire tooth width.

The step-by-step procedure is outlined below:

- Preset Flexspline Convex Arc: The design process begins by defining the convex arc profile of the flexspline tooth. This arc is typically defined in the central cross-sectional plane by its radius \( R_{f1} \) and its center coordinates relative to the flexspline neutral surface in its deformed state (at a specific rotation angle \(\phi\)).

- Generate Circular Spline Concave Arc (Using Front Section): The conjugate profile of this preset convex arc is calculated. Critically, this calculation uses the deformation parameters of the front section (\( \omega_f(\phi) \)). The front section experiences the largest radial deformation. By using this section to generate the mating concave arc of the circular spline, we ensure that at the front of the tooth—where over-deformation risk is highest—the flexspline tooth will not interfere with the circular spline root during the deepest meshing phase. The conjugate condition is governed by the equation of meshing, ensuring continuous tangency between the profiles. For a given point on the flexspline convex arc \( \mathbf{r}_f \), its corresponding point on the circular spline \( \mathbf{r}_c \) and the common normal must satisfy:

$$

\mathbf{n}_f \cdot \mathbf{v}_{fc} = 0

$$

where \( \mathbf{n}_f \) is the unit normal vector to the flexspline profile and \( \mathbf{v}_{fc} \) is the relative velocity vector between the flexspline and circular spline at that contact point, calculated using the kinematic model of the strain wave gear with front-section deformation. - Generate Circular Spline Convex Arc (Using Back Section): The next segment of the circular spline tooth profile, the convex arc, is generated. This time, the conjugate calculation is performed using the deformation parameters of the back section (\( \omega_b(\phi) \)). The back section has the smallest radial deformation. Using this section prevents interference at the tooth’s back edge during the initial meshing (engagement) phase, where the reduced deformation could otherwise cause the flexspline tooth tip to collide with the circular spline tooth tip. This step yields the tip region of the circular spline profile.

- Generate Flexspline Concave Arc (Reverse Conjugate from Front Section): Finally, the concave arc of the flexspline tooth is generated. This is done via a reverse conjugate calculation, using the newly defined convex arc of the circular spline (from Step 3) as the driving profile. To maintain consistency and ensure a smooth connection with the preset convex arc, this reverse calculation is performed again using the front section deformation parameters. The resulting concave arc, combined with the initially preset convex arc, forms the complete double-circular-arc profile of the flexspline tooth.

The core innovation is the strategic selection of the reference deformation section for each conjugate operation. This spatial approach ensures that the final three-dimensional tooth profiles are optimized for the actual deformed state of the strain wave gear assembly, effectively eliminating edge interference.

The mathematical implementation involves coordinate transformations between the flexspline and circular spline coordinate systems, which are functions of the gear ratio, the rotation angle, and the spatially-dependent radial deformation \( \omega_z(\phi) \). The conjugate points are found by solving systems of nonlinear equations derived from the meshing condition and the geometry of the circular arcs.

Finite Element Verification and Comparative Analysis

To validate the theoretical spatial deformation model and the effectiveness of the proposed design methodology, a detailed three-dimensional finite element analysis (FEA) was conducted. A model of a complete strain wave gear assembly, including the flexspline, circular spline, and wave generator with its bearing, was constructed. The material properties, contacts, and boundary conditions were carefully defined to simulate the realistic assembly process and operational loading.

Verification of Spatial Deformation

The FEA results confirm the fundamental linear trend of radial deformation along the flexspline axis, as predicted by theory. The deformation pattern transitions from the elliptical shape at the open end to a nearly circular shape at the fixed end.

The following graph and table compare the theoretical and FEA-predicted radial deformations at the front and back cross-sections along the circumference (from 0° at the major axis to 180° at the minor axis):

(Note: A detailed comparison plot would show close alignment between the theoretical cosine curves and the FEA data points. The table below quantifies the maximum discrepancies.)

| Cross-Section | Deformation Component | Max. Theoretical Value (mm) | Max. FEA Value (mm) | Maximum Absolute Error (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front Section | Radial Deformation | 0.2791 | ~0.2715 | 7.6 |

| Circumferential Deformation | 0.1429* | ~0.1386 | 4.3 | |

| Back Section | Radial Deformation | 0.2209 | ~0.2148 | 6.1 |

| Circumferential Deformation | 0.1131* | ~0.1089 | 4.2 |

* Theoretical circumferential deformation maxima are approximate and location-dependent.

The errors between the linear theoretical model and the FEA results are on the order of micrometers. This level of accuracy is well within the typical manufacturing and assembly tolerances for precision strain wave gears, confirming the adequacy of the theoretical model for design purposes. The minor deviations can be attributed to factors not captured in the simple linear shell model, such as local bending stiffness of the tooth ring and the compliance of the wave generator bearing outer ring.

Meshing Performance and Stress Analysis

The most critical validation is the comparison of meshing performance between a tooth profile designed with the proposed spatial method and one designed using a conventional planar (central section only) bidirectional conjugate method.

1. Planar Design Result: Under a simulated load torque (e.g., 30 N·m), the planar design exhibits severe issues. Clear tooth profile interference is observed in the FEA contact results. Specifically:

– At the front section, the flexspline tooth, due to larger-than-designed deformation, interferes with the circular spline tooth root at the deepest point of mesh.

– At the back section, the flexspline tooth tip interferes with the circular spline tooth tip during the engagement phase.

This interference leads to pathological stress concentrations. The von Mises stress analysis reveals a maximum stress exceeding 1100 MPa, located locally at the point of tip interference at the back section. Such high localized stress would inevitably lead to rapid pitting, scuffing, or plastic deformation of the tooth surfaces, severely compromising the strain wave gear’s life and reliability.

2. Spatial Design Result: In contrast, the strain wave gear with the spatially-designed profiles shows excellent meshing behavior. No tooth profile interference is detected across the entire engagement cycle and along the full tooth width. The contact pressure distribution is smooth and continuous. Consequently, the stress state is significantly improved. The maximum von Mises stress is reduced to a level consistent with expected material yield limits (e.g., ~264 MPa), and its location shifts to the expected high-stress region: the tooth root fillet on the major axis. This is a normal and predictable stress concentration for a loaded gear tooth.

| Design Method | Max. von Mises Stress | Stress Location | Tooth Interference | Primary Cause of High Stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planar (Conventional) | >1100 MPa | Local point at back-section tooth tip | Severe (Front root, Back tip) | Geometric interference due to unaccounted spatial deformation. |

| Spatial (Proposed) | ~264 MPa | Tooth root fillet on major axis | None | Normal bending stress from load transmission. |

The elimination of interference has further beneficial implications:

– Reduced Wear and Friction: Smooth, continuous contact promotes the formation of elastohydrodynamic lubricant films.

– Improved Efficiency: Energy losses due to sliding friction at interference points are minimized.

– Higher Load Capacity: The load is distributed more evenly across the active tooth flanks, rather than being concentrated at edges.

– Enhanced Torsional Stiffness: The simultaneous contact of multiple teeth is maintained as designed, without premature loss of contact at the ends.

Conclusions

This work establishes a rigorous framework for the design of high-performance double-circular-arc tooth profiles in strain wave gears by directly addressing the critical issue of flexspline spatial deformation. The principal contributions and findings are summarized as follows:

- Spatial Deformation Model: A linear theoretical model based on cylindrical shell deformation effectively predicts the variation of radial and circumferential deformation along the flexspline axis. The model quantitatively confirms the “tooth tilting” phenomenon, where deformation amplitudes at the front and back tooth sections differ significantly (often >±10%) from the central design section.

- Spatial Bidirectional Conjugate Method: A novel design methodology is proposed, extending the planar bidirectional conjugate principle. By strategically performing conjugate calculations using the deformation parameters of the front section (for circular spline root generation and flexspline concave generation) and the back section (for circular spline tip generation), the resulting three-dimensional tooth profiles are intrinsically compensated for spatial deformation.

- Interference Elimination: The proposed method is proven to completely avoid the tooth profile interference that plagues planar design methods. This interference, which manifests as tip contact at the back and root contact at the front of the tooth, is a major source of premature failure in strain wave gears.

- FEA Validation: Comprehensive three-dimensional finite element analysis validates both the deformation model (with errors in the micrometer range) and the superior performance of the spatially-designed profiles. The spatially-designed strain wave gear exhibits a smooth, interference-free meshing pattern, a rational stress distribution with maximum stress at the tooth root, and a drastic reduction in peak contact stress compared to the planar design.

In conclusion, the explicit incorporation of flexspline spatial deformation into the tooth profile design process is not merely an academic refinement but an engineering necessity for realizing the full potential of the strain wave gear in terms of reliability, load capacity, efficiency, and service life. The presented spatial bidirectional conjugate method provides a practical and effective tool to achieve this goal, paving the way for more robust and high-performance strain wave gear designs.

| Aspect | Planar Design | Spatial Design (Proposed) |

|---|---|---|

| Design Basis | Single central cross-section deformation. | Multiple cross-sections (Front & Back) with actual deformation. |

| Key Problem | Ignores axial deformation gradient. | Explicitly accounts for axial deformation gradient. |

| Meshing Outcome | Predictable interference at tooth ends. | Interference-free meshing across full tooth width. |

| Stress State | Abnormally high, localized stress from interference. | Normal, predictable bending stress at tooth root. |

| Practical Implication | Requires empirical corrective profile modifications (e.g., tip/root relief). | Yields an optimal theoretical profile ready for manufacturing. |

| Suitability | Low-precision or heavily derated applications. | High-performance, precision strain wave gear applications. |