The quest for high precision, compactness, and high torque-to-weight ratio in modern mechanical transmission systems has positioned strain wave gear drives as a pivotal technology in fields ranging from robotics and aerospace to precision instrumentation. The fundamental principle of strain wave gearing involves the controlled elastic deformation of a flexible spline, or flexspline, by a wave generator to achieve motion and torque transmission with high reduction ratios and near-zero backlash. At the heart of this transmission’s performance lies the geometry of the meshing teeth. While early designs utilized simple pressure-angle tooth forms, the double-circular-arc (DCTP) tooth profile has emerged as a superior design due to its ability to facilitate multiple-tooth engagement, increase load capacity, and enhance torsional stiffness. A critical design objective for DCTP in strain wave gears is to maximize the “dual-conjugated” meshing zones, where two distinct segments of the flexspline tooth simultaneously engage with the rigid circular spline (CS), thereby significantly improving motion accuracy and stiffness. This article presents a detailed, first-person methodology for the parametric optimization of the flexspline tooth profile to achieve this goal, leveraging advanced mathematical modeling and numerical techniques.

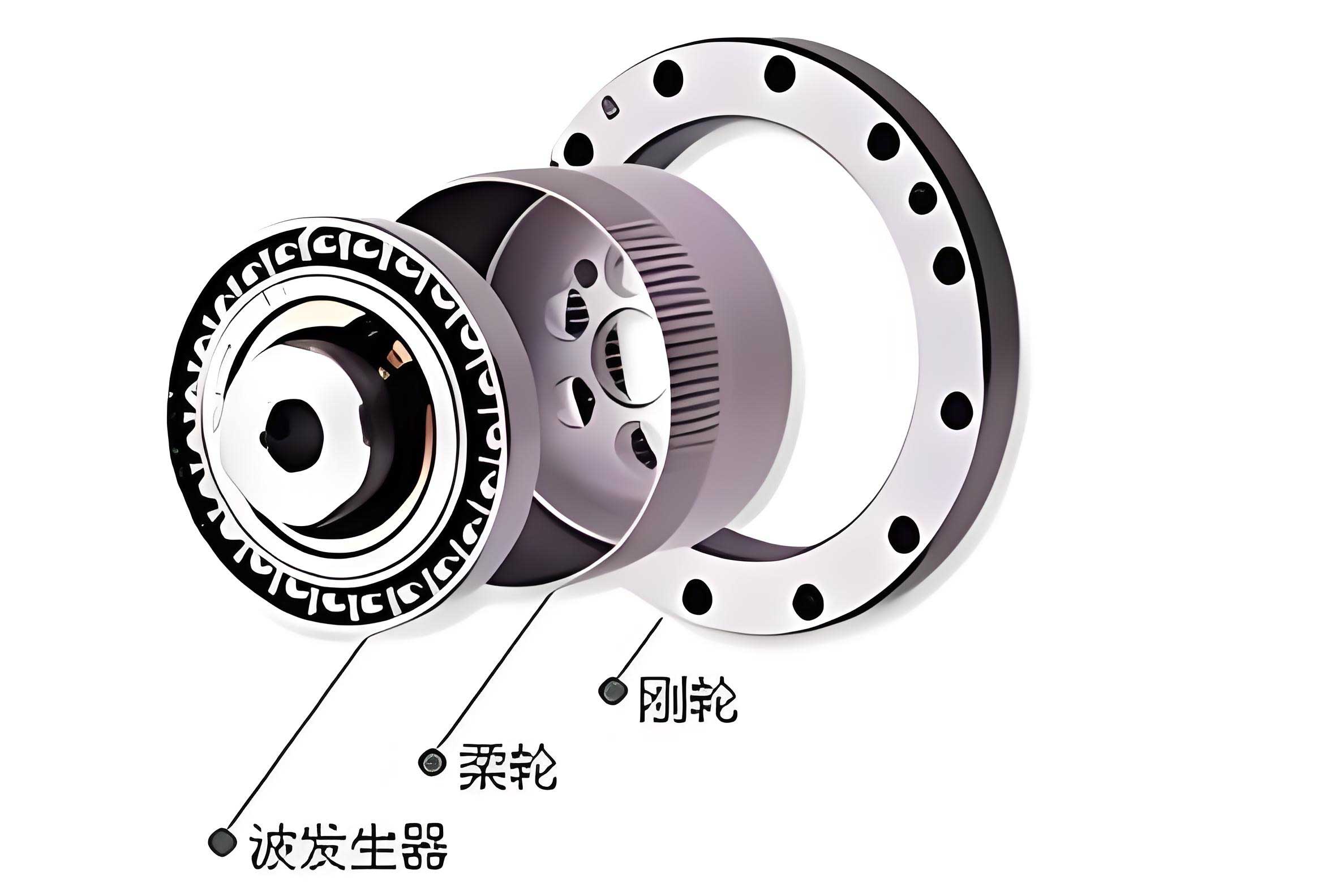

The core mechanical assembly of a strain wave gear consists of three primary components: the rigid Circular Spline (CS), the flexible Flexspline (FS), and the elliptical Wave Generator (WG). The wave generator, often an elliptical bearing or cam, is inserted into the flexspline, causing it to deform into an elliptical shape. This deformation engages the teeth of the flexspline with those of the circular spline at two diametrically opposite regions along the major axis of the ellipse. As the wave generator rotates, the points of engagement travel, creating a relative rotation between the flexspline and the circular spline. The high reduction ratio is a direct result of the difference in the number of teeth between the two splines, typically differing by 2 or 4. The unique kinematics, governed by the forced elastic deflection of the flexspline, demands a specialized tooth profile to ensure conjugate motion—where the common normal at the contact point passes through a fixed pitch point—throughout the engagement cycle. The DCTP profile, comprising convex and concave circular arcs connected by a common tangent (straight line), has proven particularly effective in meeting this challenge by creating extended and simultaneous contact regions.

To systematically analyze and optimize the DCTP for a strain wave gear, we must first establish a precise mathematical model of the flexspline tooth and its motion relative to the circular spline. We adopt a planar modeling approach, discretizing the three-dimensional problem into representative cross-sections, a common and effective simplification given the coaxial nature of the drive. For a single flexspline tooth, we define a local coordinate system \( S_1(O_1-X_1Y_1) \) attached to the tooth. The right-hand side of the DCTP profile can be uniquely and continuously described using the arc length \( u \) as a parameter via a piecewise function. The profile consists of three segments: the convex arc \( S_1 \), the common tangent (straight line) \( S_2 \), and the concave arc \( S_3 \). Their position vectors \( \mathbf{r}_i^{(1)} \) and unit normal vectors \( \mathbf{n}_i^{(1)} \) in \( S_1 \) are given below, where \( i = 1, 2, 3 \).

Convex Arc Segment (\( S_1 \), \( u \in (0, l_1) \)):

$$

\mathbf{r}_1^{(1)}(u) = \begin{bmatrix}

\rho_a \cos(\theta – u/\rho_a) + x_{oa} \\

\rho_a \sin(\theta – u/\rho_a) + y_{oa} \\

1

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

\mathbf{n}_1^{(1)}(u) = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos(\theta – u/\rho_a) \\

\sin(\theta – u/\rho_a) \\

0

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where \( l_1 = \rho_a (\theta – \gamma) \), \( \theta = \arcsin((h_a + X_a)/\rho_a) \), \( x_{oa} = -l_a \), \( y_{oa} = h_f + t – X_a \).

Common Tangent Segment (\( S_2 \), \( u \in (l_1, l_2) \)):

$$

\mathbf{r}_2^{(1)}(u) = \begin{bmatrix}

x_B + (u – l_1) \sin \gamma \\

y_B – (u – l_1) \cos \gamma \\

1

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

\mathbf{n}_2^{(1)}(u) = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos \gamma \\

\sin \gamma \\

0

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where \( l_2 = l_1 + h_l / \cos \gamma \), \( x_B = \rho_a \cos \gamma + x_{oa} \), \( y_B = \rho_a \sin \gamma + y_{oa} \).

Concave Arc Segment (\( S_3 \), \( u \in (l_2, l_3) \)):

$$

\mathbf{r}_3^{(1)}(u) = \begin{bmatrix}

x_{of} – \rho_f \cos(\gamma + (u – l_2)/\rho_f) \\

y_{of} – \rho_f \sin(\gamma + (u – l_2)/\rho_f) \\

1

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

\mathbf{n}_3^{(1)}(u) = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos(\gamma + (u – l_2)/\rho_f) \\

\sin(\gamma + (u – l_2)/\rho_f) \\

0

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where \( l_3 = l_2 + \rho_f (\arcsin((X_f + h_f)/\rho_f) – \gamma) \), \( x_{of} = (\rho_a + \rho_f)\cos \gamma + h_l \tan \gamma – l_a \), \( y_{of} = h_f + t + X_f \).

| Symbol | Description | Typical Relation/Note |

|---|---|---|

| \( h_a \) | Addendum | – |

| \( h_f \) | Dedendum | – |

| \( \rho_a \) | Radius of convex arc | – |

| \( \rho_f \) | Radius of concave arc | Optimization variable |

| \( h_l \) | Longitudinal length of common tangent | Optimization variable |

| \( \gamma \) | Inclination angle of common tangent | Optimization variable |

| \( X_a, l_a \) | Convex arc center offset parameters | Determined by geometry |

| \( X_f \) | Concave arc center offset parameter | Determined by geometry |

| \( t \) | Distance from dedendum circle to neutral layer | – |

The kinematic analysis requires defining the relative motion between the flexspline and the fixed circular spline. We establish a fixed coordinate system \( S_2(O_2-X_2Y_2) \) attached to the circular spline. The complex motion of the flexspline tooth, combining rigid-body rotation and elastic deformation induced by the wave generator, is captured through a coordinate transformation matrix \( \mathbf{M}_{21} \) and its associated invariant matrix \( \mathbf{B} \). This approach, often referred to as the improved kinematics method, elegantly encapsulates the intricate motion parameters into a single matrix \( \mathbf{B} \), which remains constant for a given wave generator profile and motion, independent of the specific tooth geometry. This greatly simplifies the conjugate tooth profile calculation. The fundamental conjugate condition, stating that the relative velocity at the contact point must be orthogonal to the common surface normal, is expressed in matrix form as:

$$

(\mathbf{n}_i^{(1)})^T \mathbf{B} \mathbf{r}_i^{(1)} = 0, \quad i = 1, 2, 3

$$

where \( \mathbf{B} = \mathbf{W}_{12}^* \frac{d\mathbf{M}_{21}}{dt} \). For a standard elliptical wave generator, the elements of \( \mathbf{B} \) are functions of the angular position \( \varphi \) on the flexspline neutral line and its radial deformation \( \omega(\varphi) \), tangential deformation \( \nu(\varphi) \), and normal rotation \( \mu(\varphi) \). The conjugate tooth profile of the circular spline in \( S_2 \) is then obtained by the transformation:

$$

\mathbf{r}_i^{(2)} = \mathbf{M}_{21} \mathbf{r}_i^{(1)}, \quad \text{subject to the condition above}.

$$

Applying this theory to a DCTP reveals a critical insight. For a given flexspline profile, the conjugate condition yields multiple theoretical conjugate curves for each segment over different angular intervals \( \alpha \) of the wave generator’s rotation. Typically, the convex arc \( S_1 \) has two conjugate zones (I and II), the common tangent \( S_2 \) has one (I), and the concave arc \( S_3 \) has one (I’). The practical circular spline profile is synthesized from parts of these curves to avoid interference. Ideally, to maximize the dual-conjugated meshing, the conjugate curve generated by the concave arc \( S_3 \) in zone I’ should precisely match the secondary conjugate curve generated by the convex arc \( S_1 \) in zone II. When these two theoretical curves coincide, it implies that during the meshing in zone I, both the convex arc and the concave arc of the flexspline tooth can potentially contact the single, unified circular spline profile simultaneously, dramatically increasing the load-sharing capacity and stiffness of the strain wave gear. The central optimization problem is therefore to adjust the key flexspline parameters—\( \gamma \), \( h_l \), and \( \rho_f \)—to force this coincidence.

We formulate this as a numerical optimization problem. Let \( f_1(x) \) represent the secondary conjugate curve from the convex arc (Curve 2) and \( f_2(x) \) represent the conjugate curve from the concave arc (Curve 5). Discretizing these curves over their common domain into \( n \) points (e.g., \( n=50 \)), we define vectors \( \mathbf{F}_1 = [f_1(x_1), …, f_1(x_n)] \) and \( \mathbf{F}_2 = [f_2(x_1), …, f_2(x_n)] \). The difference between these curves, and hence the deviation from ideal dual-conjugation, is quantified by the Euclidean distance between these vectors:

$$

T(\gamma, h_l, \rho_f) = || \mathbf{F}_1 – \mathbf{F}_2 ||

$$

This function \( T \) serves as our objective function. The optimal parameters \( (\gamma^*, h_l^*, \rho_f^*) \) are those that minimize \( T \), meaning \( \Psi = \min T(\gamma, h_l, \rho_f) \). We first conduct single-parameter sensitivity analyses to understand individual effects before proceeding to a full multi-parameter optimization.

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Module (\( m \)) | 0.3175 mm | Addendum (\( h_a \)) | 0.6m |

| Full Tooth Height (\( h \)) | 1.5m | Dedendum (\( h_f \)) | 0.9m |

| Convex Radius (\( \rho_a \)) | 0.6000 mm | \( X_a \) | 0.1009 mm |

| Distance \( t \) | 0.4150 mm | Flexspline Teeth (\( Z_r \)) | 160 |

| Circular Spline Teeth (\( Z_g \)) | 162 | Wave Generator | Elliptical Cam |

Single-Parameter Optimization: Holding \( h_l = 0.050 \) mm and \( \rho_f = 0.65 \) mm constant, we vary \( \gamma \). The function \( T(\gamma) \) exhibits a clear minimum. For the base parameters, the minimum occurs near \( \gamma^* \approx 12.1^\circ \). Changing \( \gamma \) away from this optimum causes \( T \) to increase rapidly, indicating a strong sensitivity and a precise optimal value for achieving curve coincidence. Similarly, optimizing \( h_l \) with fixed \( \gamma \) and \( \rho_f \) yields a distinct minimum, for example, \( h_l^* \approx 0.047 \) mm for the base case. Optimizing \( \rho_f \) alone also shows a minimum, but the variation of \( T \) with respect to \( \rho_f \) over a practical range (e.g., 0.55 mm to 0.65 mm) is noticeably less pronounced compared to variations with \( \gamma \) or \( h_l \). This preliminary analysis suggests that the objective function \( T \) is most sensitive to the common tangent parameters \( \gamma \) and \( h_l \), and less sensitive to the concave arc radius \( \rho_f \).

Multi-Parameter Optimization: To find the global optimum, we perform a coordinated search over the three-dimensional parameter space defined by reasonable intervals for each variable: \( \gamma \in [11^\circ, 13^\circ] \), \( h_l \in [0.02, 0.08] \) mm, \( \rho_f \in [0.55, 0.65] \) mm. Discretizing each interval and evaluating \( T \) for all parameter combinations, we identify the global minimum.

$$

\Psi = \min T(\gamma, h_l, \rho_f) = T(11.52^\circ, 0.0408 \text{ mm}, 0.562 \text{ mm}) \approx 2.1 \times 10^{-3} \text{ mm}

$$

At this optimum, the maximum pointwise deviation between \( f_1(x) \) and \( f_2(x) \) is below \( 8 \times 10^{-4} \) mm, and the average deviation is around \( 4 \times 10^{-4} \) mm. For precision strain wave gear applications, this level of coincidence is functionally equivalent to perfect matching, effectively maximizing the dual-conjugated meshing zone.

| Parameter | Sensitivity of \( T \) | Practical Manufacturing Consideration | Optimization Strategy Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Tangent Angle (\( \gamma \)) | High | Relatively easy to control via tooling setup or grinding. | Should be set close to its optimal value for performance. |

| Tangent Length (\( h_l \)) | High | Easily controlled in tool profile generation. | Should be set close to its optimal value for performance. |

| Concave Arc Radius (\( \rho_f \)) | Low | May be constrained by available standard cutting tools or hobs for economic batch production. | Can be adjusted away from its theoretical optimum with minimal performance penalty to accommodate tooling constraints. |

The analysis reveals a crucial practical insight for the design of strain wave gear drives. While the multi-parameter optimization yields a mathematically optimal set \( (\gamma^*, h_l^*, \rho_f^*) \), the low sensitivity of \( T \) to \( \rho_f \) provides valuable design flexibility. In real-world manufacturing, the concave arc radius \( \rho_f \) is often dictated by the availability of standardized cutting tools or hobs. A designer can therefore select a standard, readily available tool radius for \( \rho_f \) that is near the optimum, and then finely adjust the highly sensitive parameters \( \gamma \) and \( h_l \) to re-optimize and minimize \( T \) for that chosen \( \rho_f \). This two-stage approach marries optimal meshing performance with manufacturing practicality and economy, a vital consideration for the successful implementation of high-performance strain wave gearing systems.

In conclusion, the methodology presented here provides a rigorous and practical framework for the optimization of double-circular-arc tooth profiles in strain wave gear drives. By establishing a piecewise arc-length parameterization of the flexspline tooth and employing the invariant matrix method for kinematic analysis, the complex problem of conjugate theory is rendered tractable. Defining an objective function based on the coincidence of critical theoretical conjugate curves directly targets the enhancement of “dual-conjugated” meshing, a key driver for superior stiffness and accuracy. The subsequent single and multi-parameter optimization not only identifies optimal parameter sets but also elucidates the sensitivity landscape, empowering designers to make informed trade-offs between peak theoretical performance and manufacturing constraints. This optimization process is fundamental to advancing the state-of-the-art in strain wave gear design, enabling their use in ever more demanding precision applications.