In the realm of precision engineering and robotics, the strain wave gear stands out as a pivotal component due to its exceptional characteristics, including high reduction ratios, compactness, minimal backlash, and efficient power transmission. As a key element in robotic joints and aerospace mechanisms, the strain wave gear relies on the elastic deformation of a flexible wheel, often termed the flexspline, which undergoes cyclic stress during operation. This study delves into the assembly stress analysis of the flexible wheel within a strain wave gear system, employing finite element methods to explore how varying geometric parameters influence stress distribution. The primary objective is to elucidate the stress behavior under both no-load and loaded conditions, providing actionable insights for optimizing the design and enhancing the durability of strain wave gear transmissions. Throughout this investigation, the term ‘strain wave gear’ is emphasized to underscore its significance in modern mechanical systems.

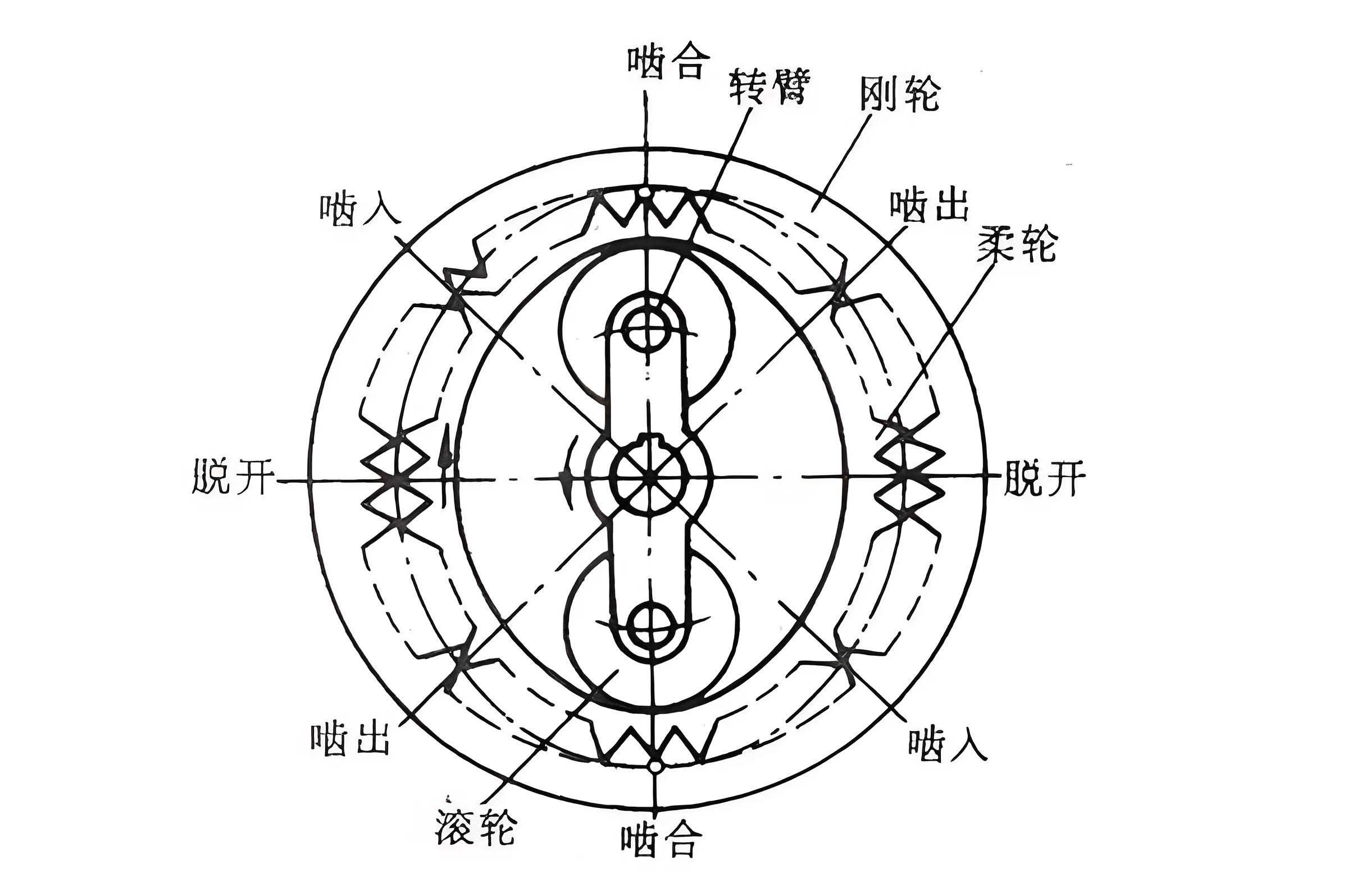

The strain wave gear mechanism operates on the principle of controlled elastic deformation, where a wave generator, typically an elliptical cam or bearing, is inserted into a flexible wheel, causing it to deform into an elliptical shape. This deformation enables meshing with a rigid circular spline, resulting in relative motion and torque transmission. The flexible wheel, often designed as a thin-walled cup-shaped structure, is subjected to alternating stresses due to repeated deformation, making it susceptible to fatigue failure. Consequently, a thorough understanding of stress distribution under assembly and operational loads is paramount for reliability. In this work, we leverage ANSYS finite element software to simulate the assembly process and analyze stress patterns, focusing on parameters such as aspect ratio, tooth width, and wall thickness. By adopting a control variable approach, we isolate the effects of each parameter, thereby offering a systematic framework for design improvements in strain wave gear applications.

Finite element modeling begins with the geometric construction of the flexible wheel and wave generator. The flexible wheel is modeled as a cup-shaped component with involute teeth, characterized by dimensions like tooth tip diameter, inner and outer wall diameters, tooth width, cylinder wall thickness, transition arc radius, flange thickness, and bottom hole diameter. The wave generator is represented as an elliptical cam with specified major and minor axis diameters. Material properties are assigned based on 55Si2Mn steel, with an elastic modulus of 197 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.2548. The wave generator is treated as a rigid body to simplify contact interactions, while the flexible wheel is discretized using hexahedral elements via swept meshing after partitioning into regions like the tooth ring, cylinder, transition arc, and flange. This meshing strategy ensures accuracy and computational efficiency, with mesh convergence verified through refinement studies.

Contact conditions are defined using a “rigid-flexible” surface-to-surface approach, where the wave generator’s outer surface serves as the target and the flexible wheel’s inner surface as the contact. Frictional contact with a coefficient of 0.1 is assumed, and the augmented Lagrange method is employed for solution stability. Boundary conditions involve fixing the flange at the bottom of the flexible wheel to simulate mounting constraints. The assembly simulation focuses on static conditions without rotational motion, allowing us to examine preload stresses induced by the wave generator. This setup forms the basis for subsequent analyses under various loading and parametric scenarios.

Under no-load conditions, the assembly of the wave generator into the flexible wheel results in characteristic elliptical deformation. The deformation is most pronounced at the cup mouth along the major axis of the wave generator and attenuates axially toward the flange. This attenuation can be mathematically described by an exponential decay function:

$$ \delta(z) = \delta_0 \cdot e^{-\alpha z} $$

where $\delta(z)$ represents the radial deformation at axial position $z$, $\delta_0$ denotes the maximum deformation at the cup mouth (measured as 0.79634 mm in our simulation), and $\alpha$ is a decay constant influenced by material stiffness and geometry. For the modeled strain wave gear, $\alpha \approx 0.15 \, \text{mm}^{-1}$, indicating a rapid decrease in deformation with distance from the mouth.

The stress distribution under no-load is derived from the von Mises criterion, which accounts for multi-axial stress states. The equivalent stress $\sigma_{\text{eq}}$ is calculated as:

$$ \sigma_{\text{eq}} = \sqrt{ \frac{1}{2} \left[ (\sigma_1 – \sigma_2)^2 + (\sigma_2 – \sigma_3)^2 + (\sigma_3 – \sigma_1)^2 \right] } $$

where $\sigma_1$, $\sigma_2$, and $\sigma_3$ are the principal stresses. Our results indicate that the maximum equivalent stress occurs at the tooth root near the major axis, reaching values up to 300 MPa. The stress distribution along the cylinder wall exhibits a gradual reduction axially, albeit with localized increases near the transition arc due to geometric discontinuities. Circumferentially, stress varies significantly, with the major axis experiencing higher stresses compared to the minor axis. This pattern can be approximated by the function:

$$ \sigma(\theta, z) = \sigma_{\text{max}} \cdot \cos^2(\theta) \cdot e^{-\beta z} $$

where $\theta$ is the angular coordinate (0° at the major axis), $\sigma_{\text{max}}$ is the peak stress at the cup mouth, and $\beta$ is an attenuation factor. The symmetry of stress about the X and Y axes under no-load aligns with the elliptical deformation imposed by the wave generator in the strain wave gear assembly.

To quantify the stress variations, we extract data along critical paths and summarize key findings in tables. For instance, the axial stress profile on the cylinder outer wall shows an initial rise near the tooth ring, followed by a decline and a slight resurgence near the transition arc. This behavior underscores the complexity of stress distribution in thin-walled structures like the flexible wheel of a strain wave gear.

Under loaded conditions, torque application alters the stress landscape. We simulate torques of 0 N·m, 40 N·m, and 80 N·m by applying tangential forces to nodes on the tooth pitch circle. The torque $T$ relates to the tangential force $F_t$, number of nodes $n$, and pitch radius $r_p$ through:

$$ T = F_t \cdot n \cdot r_p $$

As load increases, the overall stress magnitude escalates, and the location of maximum stress shifts in the direction of torque application. For example, at 40 N·m, the peak stress rises to approximately 350 MPa and shifts by 15°, while at 80 N·m, it reaches 400 MPa with a 30° shift. This shift arises from additional bending moments induced by the torque, breaking the symmetry observed under no-load. The relationship between applied torque and maximum stress can be linearized as:

$$ \sigma_{\text{max}}(T) = \sigma_0 + k_T \cdot T $$

where $\sigma_0$ is the no-load stress and $k_T$ is a proportionality constant (approximately 1.25 MPa/N·m based on our data). This linear trend highlights the sensitivity of the strain wave gear flexible wheel to operational loads, necessitating careful consideration during design.

We now turn to the impact of geometric parameters on stress under no-load conditions. Using the control variable method, we vary aspect ratio, wall thickness, and tooth width independently while holding other dimensions constant. The results are encapsulated in tables below, along with empirical formulas derived from curve fitting.

First, the aspect ratio (AR), defined as the ratio of cylinder length to diameter, influences stress significantly. Table 1 presents the maximum equivalent stress for different aspect ratios, demonstrating an inverse relationship.

| Aspect Ratio (AR) | Maximum Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1050 |

| 0.6 | 900 |

| 0.7 | 800 |

| 0.8 | 700 |

| 0.9 | 650 |

| 1.0 | 631 |

The data reveals a 39% reduction in stress as AR increases from 0.5 to 1.0. This trend can be modeled by a power-law equation:

$$ \sigma_{\text{max}}(AR) = k_1 \cdot AR^{-n_1} $$

where $k_1 = 1200 \, \text{MPa}$ and $n_1 = 0.8$ provide a good fit. The decreasing stress with higher AR is attributed to better load distribution along the cylinder length, reducing stress concentrations. However, larger AR may compromise compactness, a key advantage of strain wave gear systems, thus necessitating a trade-off in design optimization.

Second, the wall thickness of the cylinder ($t$) affects both stiffness and stress. Table 2 summarizes stress values for varying thicknesses.

| Wall Thickness, $t$ (mm) | Maximum Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|

| 0.7 | 850 |

| 0.8 | 880 |

| 0.9 | 910 |

| 1.0 | 940 |

| 1.1 | 950 |

| 1.2 | 960 |

Contrary to intuition, stress increases with wall thickness, albeit at a diminishing rate, approaching an asymptotic value around 960 MPa. This behavior stems from increased rigidity leading to higher stress concentrations under deformation. The relationship can be expressed as an exponential saturation model:

$$ \sigma_{\text{max}}(t) = \sigma_{\infty} – k_2 \cdot e^{-\beta t} $$

with $\sigma_{\infty} = 960 \, \text{MPa}$, $k_2 = 110 \, \text{MPa}$, and $\beta = 2.0 \, \text{mm}^{-1}$. This implies that beyond a thickness of 1.2 mm, further thickening yields minimal stress reduction, while thinner walls risk excessive deformation or buckling. Hence, an optimal thickness around 1.0 mm may balance stress and structural integrity in strain wave gear flexible wheels.

Third, tooth width ($w$) plays a critical role in stress distribution. Table 3 outlines the stress variation with tooth width.

| Tooth Width, $w$ (mm) | Maximum Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|

| 10 | 550 |

| 11 | 650 |

| 12 | 750 |

| 13 | 850 |

| 14 | 900 |

| 15 | 967 |

A 43% stress increase is observed as tooth width expands from 10 mm to 15 mm, indicating a strong positive correlation. This can be approximated by a linear function:

$$ \sigma_{\text{max}}(w) = k_3 \cdot w + c $$

where $k_3 = 83.4 \, \text{MPa/mm}$ and $c = -284 \, \text{MPa}$. Wider teeth enhance rigidity but also amplify stress due to uneven load sharing across the tooth ring. Designers of strain wave gear systems must therefore select tooth widths that compromise between strength and stress limits, possibly targeting intermediate values like 12-13 mm based on our data.

To synthesize these parametric effects, we propose a combined empirical model for maximum stress in the flexible wheel of a strain wave gear under no-load:

$$ \sigma_{\text{max}} = C \cdot (AR)^{-0.8} \cdot (1 + \gamma t) \cdot (1 + \eta w) $$

where $C$, $\gamma$, and $\eta$ are constants derived from regression analysis. This model, though simplified, captures the interactive influences of key geometric parameters and can serve as a preliminary design tool for strain wave gear components.

Further analysis considers the stress distribution across different sections of the flexible wheel. For instance, at the tooth ring cross-section (z=0), circumferential stress exhibits fluctuations with peaks at the major and minor axes, as described by:

$$ \sigma_{\theta}(\theta) = \sigma_a \cos(2\theta) + \sigma_b $$

where $\sigma_a$ and $\sigma_b$ are constants determined from FEA results. These fluctuations underscore the periodic loading experienced by the strain wave gear during operation, which can lead to fatigue if not properly managed.

In discussing the implications of our findings, it is evident that the strain wave gear’s performance hinges on the flexible wheel’s stress response. The asymmetric stress shift under load necessitates designs that account for torque direction, possibly through asymmetric reinforcement or material grading. Moreover, the parametric trends highlight trade-offs: higher aspect ratios reduce stress but increase size, thicker walls may not always lower stress, and wider teeth elevate stress despite added strength. These insights are crucial for advancing strain wave gear technology, particularly in robotics where compactness and reliability are paramount.

Future work should extend this analysis to dynamic conditions, incorporating rotational speeds and thermal effects, which are common in operational strain wave gear systems. Experimental validation using strain gauges or optical methods would corroborate our FEA predictions. Additionally, fatigue life estimation based on stress amplitudes could guide material selection and safety factors. The continuous evolution of strain wave gear designs benefits from such detailed stress analyses, paving the way for more robust and efficient transmission systems.

In conclusion, through finite element simulation, we have examined the assembly stress in the flexible wheel of a strain wave gear transmission mechanism. Under no-load, stress distribution is symmetric and concentrated at the tooth ring near the major axis, with deformation decaying axially. Applied torque increases stress magnitudes and induces asymmetric shifts. Parametric studies reveal that aspect ratio inversely affects stress, while wall thickness and tooth width have direct but saturating effects. These outcomes provide a foundation for optimizing flexible wheel geometries in strain wave gear applications, ultimately enhancing durability and performance in demanding mechanical systems.