In the realm of precision motion control and robotics, the demand for compact, high-ratio, and accurate transmission systems is ever-growing. Among the various solutions, strain wave gear systems, often referred to as harmonic drives, have emerged as a cornerstone technology due to their exceptional performance characteristics. This article delves into the advanced design and performance evaluation of a strain wave gear system, focusing on the development of a triple-circular-arc spatial tooth profile and its impact on torsional stiffness under load. The primary objective is to establish a relationship between measurable torsional stiffness hysteresis and the immeasurable meshing characteristics, such as the number of engaging teeth, thereby providing a valuable metric for assessing and improving transmission capability.

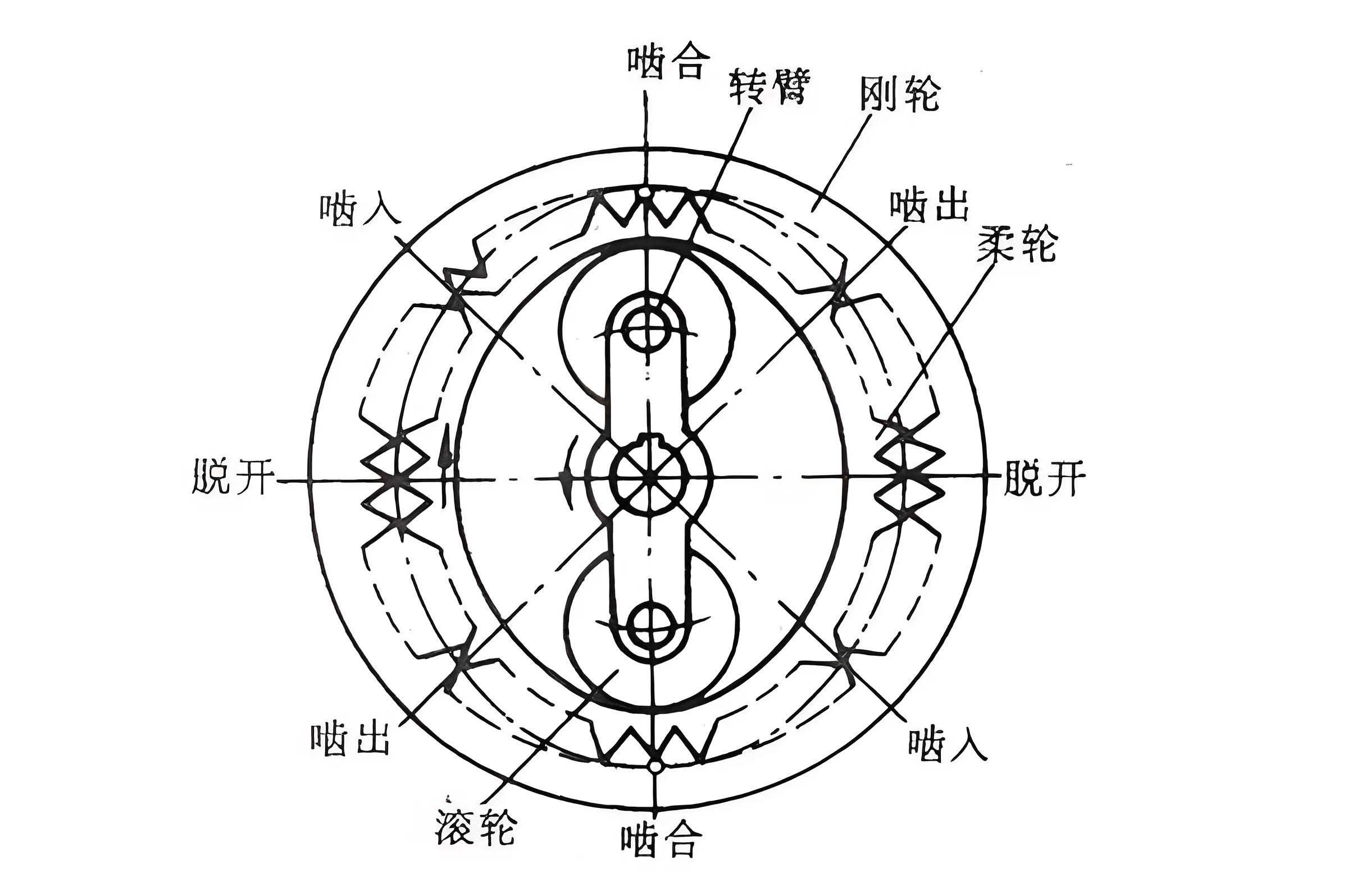

The fundamental operation of a strain wave gear relies on the elastic deformation of a flexible component, known as the flexspline, by a wave generator. This deformation creates a moving elliptical wave that engages teeth with a rigid circular spline, resulting in high reduction ratios within a compact envelope. The performance, including load capacity, precision, and stiffness, is heavily influenced by the tooth profile geometry and its spatial configuration. Traditional designs often utilize planar tooth profiles, but these can lead to suboptimal contact under load due to the complex, tapered deformation of the flexspline. To address this, a spatial tooth profile design is proposed, where the flexspline tooth geometry varies along its axial length to better match the deformed state induced by the wave generator.

The core of this work involves constructing a triple-circular-arc tooth profile for the flexspline. This profile consists of four smoothly connected circular arcs, offering greater flexibility in optimizing engagement characteristics compared to simpler profiles. The design parameters for the flexspline tooth profile are summarized in Table 1. The key parameters include the addendum height \(h_a\), dedendum height \(h_f\), radii of the upper, middle, and lower arcs (\(R_1, R_2, R_3\)), and the fillet radius \(R_4\). The design is performed on a nominal cross-section of the flexspline.

| Symbol | Value (mm) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| \(z_1\) | 100 | Number of teeth on flexspline |

| \(m\) | 0.5066 | Module |

| \(h_a\) | 0.2837 | Addendum height |

| \(h_f\) | 0.3192 | Dedendum height |

| \(h_{la}\) | 0.2324 | Middle arc top height |

| \(h_{lf}\) | 0.0016 | Middle arc bottom height |

| \(R_1\) | 0.1317 | Upper arc radius |

| \(R_2\) | 1.3679 | Middle arc radius |

| \(R_3\) | 2.4318 | Lower arc radius |

| \(R_4\) | 0.3040 | Fillet radius |

| \(S\) | 0.5659 | Tooth thickness at pitch circle |

The motion of the flexspline teeth relative to the circular spline is governed by the deformation imposed by the elliptical wave generator. The neutral curve of the flexspline, initially a circle of radius \(r_m\), deforms into an elliptical shape described by the polar equation \(\rho(\phi_1)\). The relationship between the angular position on the undeformed circle \(\phi\) and on the deformed ellipse \(\phi_1\) is given by the constant arc length condition:

$$

\phi = \frac{1}{r_m} \int_{0}^{\phi_1} \sqrt{\rho^2 + \left(\frac{d\rho}{d\phi_1}\right)^2} d\phi_1

$$

The wave generator’s major axis rotates relative to the circular spline, and the orientation of the flexspline tooth symmetry line is determined by a combination of the polar angle and the normal deflection. The position of a point on the flexspline tooth profile in the coordinate system fixed to the circular spline can be expressed as:

$$

\begin{aligned}

x_{C}^{O_f} &= \rho \sin \theta \\

y_{C}^{O_f} &= \rho \cos \theta

\end{aligned}

$$

where \(\theta = \phi_1 – (z_1 / z_2) \phi\) and \(z_2\) is the number of teeth on the circular spline (102 in this case). This kinematic framework is essential for tracing the envelope of the flexspline tooth motion, which is used to design the conjugate tooth profile for the circular spline.

For the strain wave gear system to achieve optimal performance under load, the initial no-load backlash must be minimized and uniformly distributed. Backlash is defined as the shortest circumferential distance between the working tooth surfaces of a mating pair within the engagement zone. The spatial variation of this backlash is critical. To improve this, a radial modification strategy is applied to the flexspline tooth profile along its axial direction. The goal is to make the outer envelopes of the meshing motion from different axial cross-sections coincide as closely as possible after the flexspline undergoes its characteristic tapered deformation. Assuming a linear variation of radial displacement from the cup bottom to the open end (the “straight generator” assumption), the deformed radius at an axial coordinate \(z\) is:

$$

\rho(\phi, z) = [\rho(\phi) – r_m] (z / z_0) + r_m \quad \text{for} \quad 0 < z < l

$$

where \(z_0\) is the axial distance from the cup bottom to the design reference cross-section, and \(l\) is the total length of the cylindrical shell. Seven cross-sections along the axial direction are defined, and their respective radial modification values are iteratively adjusted to minimize the deviation of their meshing envelopes from a target envelope (typically at a middle section). The optimized modification amounts for these sections are listed in Table 2.

| Cross-Section | Axial Position from Cup Bottom, \(z\) (mm) | Radial Modification, \(H_S\) (\(\mu m\)) |

|---|---|---|

| ZS1 | 25.3 | 76.82 |

| ZS2 | 23.678 | 46.55 |

| ZS3 | 22.057 | 17.27 |

| ZS4 | 20.435 | -8.00 |

| ZS5 | 19.223 | 1.81 |

| ZS6 | 18.012 | 13.62 |

| ZS7 | 16.8 | 30.40 |

Using the envelope method based on the outer envelope of the modified flexspline tooth motion, the conjugate tooth profile for the circular spline is designed. This profile is also a triple-circular-arc shape. Its key geometric parameters are provided in Table 3. The design ensures continuous conjugation and minimal functional backlash within the major engagement zone.

| Symbol | Value (mm) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| \(z_2\) | 102 | Number of teeth on circular spline |

| \(r_{a2}\) | 25.5 | Addendum circle radius |

| \(r_{f2}\) | 26.1122 | Dedendum circle radius |

| \(R_5\) | 0.6145 | Upper arc radius |

| \(R_6\) | 1.8705 | Middle arc radius |

| \(R_7\) | 0.7979 | Lower arc radius |

| \(R_8\) | 0.3 | Tip fillet radius |

To evaluate the load transmission performance of this spatial tooth profile design, a detailed finite element analysis (FEA) model is constructed. The model includes three main components: the cup-shaped flexspline with the spatially varying triple-circular-arc tooth profile, the circular spline with a planar triple-circular-arc tooth profile, and a simplified representation of the wave generator’s outer ring. The flexspline model is generated by creating tooth profiles at the seven defined cross-sections with their respective radial modifications and then performing an axial lofting operation within the FEA preprocessor to form a continuous solid. The circular spline is modeled as a rigid ring with its planar tooth profile extruded axially. The wave generator is simplified to a rigid elliptical shell of narrow width (\(b_w = 0.5 \text{ mm}\)) to represent its primary contact surface with the flexspline’s inner wall, ignoring minor effects from unsupported segments of the bearing raceway which have negligible impact on loaded conditions.

The material properties are assigned as linear elastic with Young’s modulus \(E = 210 \text{ GPa}\) and Poisson’s ratio \(\mu = 0.3\). The flexspline and circular spline are meshed with SOLID186 higher-order 3D solid elements, while the wave generator shell is meshed with SHELL63 elements. Careful attention is paid to mesh quality at the contact regions. The contact pairs are defined as follows: the tooth surfaces of the circular spline are set as target surfaces (TARGE170), and the tooth surfaces of the flexspline are set as contact surfaces (CONTA174). Similarly, the outer surface of the wave generator shell is the target, and the inner cylindrical surface of the flexspline is the contact surface. A friction coefficient of 0.1 is applied to all contacting surfaces to simulate realistic interaction.

Boundary conditions are applied to simulate the assembly and loading of the strain wave gear. The circular spline is fixed completely on its outer circumference. The wave generator is also fully constrained in space. The flexspline’s cup bottom flange has all degrees of freedom constrained except for rotation about its axis. To apply a pure torque to the output (the flexspline flange), a MASS21 element is created and coupled to all nodes on the outer rim of the flange. The load torque is then applied directly to this mass element. The analysis simulates the quasi-static assembly by first solving for the initial contact state with the wave generator deforming the flexspline. Subsequently, a series of load steps apply progressively increasing torque to the flexspline, up to and beyond the rated load torque (RLT) of \(25 \text{ N·m}\), followed by unloading and reverse loading to capture the full hysteresis behavior.

The simulation results first verify the no-load backlash distribution. The circumferential backlash is calculated from the deformed positions of the flexspline teeth at various axial sections and compared with theoretical predictions. The spatial design successfully yields a very small and uniformly distributed backlash in the primary engagement zone (near the middle cross-section), with values under \(4 \mu m\) over an engagement arc from approximately \(3.6^\circ\) to \(33^\circ\) from the major axis. This favorable initial condition promotes multi-tooth engagement even under light loads.

Under applied load, the distribution of meshing forces on the tooth surfaces is analyzed. Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of this distribution for one side of the engagement region at different load levels: 3%, 10%, 20%, 50%, and 100% of the RLT. At a mere 3% RLT, a small number of teeth near the major axis begin to share the load. By 10% RLT, the engagement zone expands to cover about \(40^\circ\), and this zone remains relatively constant with further load increase. This demonstrates that the wide-range minimal-backlash design effectively achieves a high number of contacting teeth at low loads. The force distribution within the engagement zone (\(3.6^\circ\) to \(39.6^\circ\)) is notably uniform, indicating good load-sharing characteristics of the proposed triple-circular-arc spatial profile for the strain wave gear.

The central performance metric investigated is the torsional stiffness of the output (flexspline) relative to the fixed input (wave generator/circular spline assembly). The simulation follows the standard test method: after assembly, a slowly increasing torque is applied to the output, then decreased, followed by torque application in the opposite direction. The resulting torque-angle relationship forms a hysteresis loop. The computed hysteresis curve is shown in Figure 2. The curve exhibits a distinct nonlinear region at low torque levels, transitioning into a more linear region at higher loads. The slope of this curve at any point represents the instantaneous torsional stiffness \(K\), calculated as:

$$

K = \frac{\Delta T}{\Delta \theta}

$$

where \(\Delta T\) is the incremental torque and \(\Delta \theta\) is the corresponding incremental angular displacement.

To quantify the stiffness variation, the torque range is divided into segments, and the average stiffness for each segment is computed. The relationship between this calculated torsional stiffness and the number of teeth in active contact (extracted from the FEA solution for each load step) is then established. The results are summarized in Table 4 and graphically depicted in Figure 3. A strong positive correlation is observed: the torsional stiffness increases sharply as more teeth come into contact during the initial low-load phase (up to about 20% RLT). Once the maximum practical number of teeth is engaged, the stiffness stabilizes and remains nearly constant, leading to the linear portion of the hysteresis curve. This finding is crucial because the number of meshing teeth is extremely difficult to measure in a physical strain wave gear assembly, whereas the torsional stiffness hysteresis is a standard, measurable performance characteristic.

| Load Level (% of RLT) | Approx. Torque (N·m) | Estimated Number of Meshing Teeth (One Side) | Torsional Stiffness, \(K\) (N·m/arcsec) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3% | 0.75 | 3-5 | Low, Highly Nonlinear |

| 10% | 2.5 | ~12 | Increasing Rapidly |

| 20% | 5.0 | ~15 | Near Maximum |

| 50% | 12.5 | ~16 | Maximum, Stable |

| 100% | 25.0 | ~16 | Maximum, Stable |

The implications of this relationship are significant for the design and evaluation of strain wave gear systems. By analyzing the shape of the experimentally obtained torsional stiffness hysteresis curve, engineers can infer the engagement behavior of the tooth profiles. A short, sharply rising nonlinear segment followed by a long linear segment indicates that the gear design achieves multi-tooth engagement quickly under low load, which is desirable for high positional accuracy and load capacity. Conversely, a prolonged nonlinear region suggests delayed multi-tooth contact, potentially leading to higher stress concentrations and greater elastic hysteresis loss. Therefore, the torsional stiffness characteristic serves as a powerful indirect indicator of the quality of the tooth profile design and manufacturing accuracy in a strain wave gear.

In conclusion, this work presents a comprehensive methodology for designing and evaluating a high-performance strain wave gear system. The proposed triple-circular-arc spatial tooth profile for the flexspline, coupled with its conjugate planar profile for the circular spline, effectively minimizes no-load backlash and promotes uniform load distribution. The finite element simulation model successfully captures the complex nonlinear behavior under load. The key finding is the strong positive correlation between the output torsional stiffness and the number of teeth in contact. This allows for the assessment of critical, yet immeasurable, meshing characteristics through standard stiffness tests. For designers, aiming for a spatial tooth profile that yields a rapid transition to linear stiffness behavior is advantageous, as it maximizes the benefits of multi-tooth engagement—enhancing load capacity, reducing wear, and improving the precision and repeatability of the strain wave gear transmission. Future work may explore the optimization of the modification law using this stiffness relationship as an objective function and investigate the dynamic performance based on the characterized nonlinear stiffness.

The mathematical foundation for the kinematic analysis can be further elaborated. The elliptical deformation of the flexspline neutral curve is given by:

$$

\rho(\phi_1) = \frac{a b}{\sqrt{a^2 \sin^2 \phi_1 + b^2 \cos^2 \phi_1}}

$$

where \(a = r_m + w_0\) and \(b = \frac{1}{2}r_m – \frac{7}{9}a + \frac{4}{9}\sqrt{a(3r_m – 2a)}\), with \(w_0\) being the maximum radial deformation. The derivative \(\rho'(\phi_1)\) is needed for calculating the normal tilt angle \(\theta_{uz}\) of the flexspline tooth:

$$

\theta_{uz} = -\arctan\left( \frac{\rho'(\phi_1)}{\rho(\phi_1)} \right)

$$

The final orientation angle \(\Phi\) of the flexspline tooth symmetry line relative to the circular spline’s tooth space symmetry line is:

$$

\Phi = \theta_{uz} + \theta = \theta_{uz} + \left( \phi_1 – \frac{z_1}{z_2} \phi \right)

$$

These equations are integral to the envelope-based tooth profile generation process for the circular spline in a strain wave gear system.

Furthermore, the stiffness model can be related to the structural compliance of the flexspline. The total angular deflection \(\theta\) under torque \(T\) is a sum of contributions from the torsional deformation of the cup body, the bending and shear deformation of the teeth, and the local contact deformation. The nonlinearity arises because the number of load-sharing teeth \(N_{mesh}\) is a function of the load itself. A simplified expression for the overall compliance \(C = 1/K\) might be:

$$

C(T) \approx \frac{C_{cup} + C_{teeth}(T) + C_{contact}(T)}{N_{mesh}(T)}

$$

where \(C_{cup}\) is the constant compliance of the cup, and \(C_{teeth}\) and \(C_{contact}\) are effective compliances that may also vary with load. The inverse relationship with \(N_{mesh}(T)\) explains the observed stiffness increase. When \(N_{mesh}(T)\) saturates, the stiffness reaches its maximum. This conceptual model reinforces the simulation findings and provides a theoretical link between meshing characteristics and macroscopic stiffness in a strain wave gear.

In summary, the advanced design and analysis presented here underscore the importance of integrated spatial tooth profile design and thorough finite element simulation for unlocking the full potential of strain wave gear technology. By establishing a clear link between measurable torsional hysteresis and internal meshing state, this work provides engineers with a valuable tool for performance prediction and design refinement, ultimately contributing to more reliable and capable precision drive systems across various industrial and robotic applications.