In modern precision servo transmission systems, such as robotic joints, the demand for compact and reliable strain wave gear mechanisms has increased significantly. Lubrication plays a critical role in ensuring the longevity and efficiency of these systems. By introducing a lubricant between two moving surfaces, a lubricating film is formed, separating the surfaces and transforming dry friction into fluid friction, thereby reducing wear and extending service life. However, maintaining adequate lubrication in strain wave gear drives, especially under vertical or inclined mounting conditions, remains a challenge. Traditional methods, like gravity-fed lubrication or oil-slinger cups, often fail to provide continuous lubricant supply to critical meshing areas, such as the wave generator and flexspline interface. This can lead to mixed or dry friction states, accelerating wear and potentially causing failure. To address this, we propose a novel vane-type active lubrication system designed to ensure consistent lubricant delivery in strain wave gear applications, regardless of mounting orientation or input shaft rotation direction.

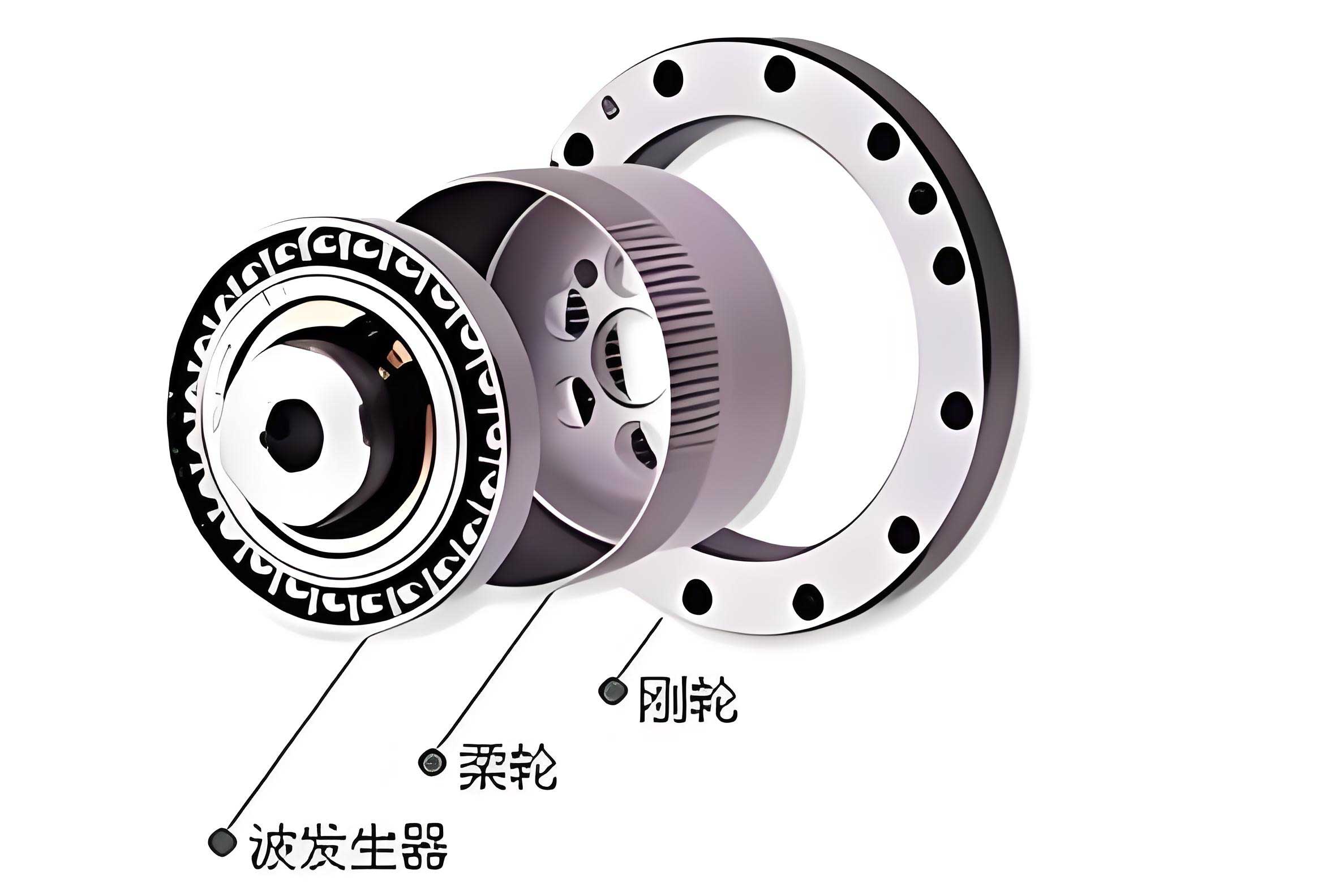

The strain wave gear, also known as a harmonic drive, is widely used in robotics and aerospace due to its high reduction ratio, compactness, and precision. Its operation involves the elastic deformation of a flexspline by a wave generator, creating a moving meshing zone with a circular spline. Effective lubrication in this zone is essential to minimize friction and wear. However, in vertical installations, lubricant tends to drain away from the meshing area due to gravity, while traditional oil-slinger cups may not efficiently redirect lubricant to the wave generator and flexspline interface. Moreover, with the trend toward miniaturization and the use of strain wave gear designs without flexible bearings, ensuring reliable lubrication becomes even more critical. Our study focuses on developing an active lubrication system that actively pumps lubricant to the necessary locations, overcoming the limitations of passive methods.

To design an effective active lubrication system for strain wave gear drives, we first analyzed the lubricant leakage characteristics under different operating conditions. Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), we modeled the lubricant flow between the wave generator and flexspline. The wave generator, typically an elliptical cam, and the flexspline form a thin film region filled with lubricant. For our analysis, we considered a common strain wave gear configuration with an elliptical sliding bearing model. The geometric parameters for the CFD model are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major axis of wave generator outer surface | a1 | 97.5 | mm |

| Minor axis of wave generator outer surface | b1 | 97.4 | mm |

| Major axis of flexspline inner surface | a2 | 97.4 | mm |

| Minor axis of flexspline inner surface | b2 | 95.2 | mm |

| Width in z-direction | L | 20 | mm |

The lubricant used in our analysis is a grease with NLGI grade II, modeled using the Herschel-Bulkley constitutive equation to account for its non-Newtonian behavior. The parameters for the lubricant are given in Table 2.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | ρ | 930 | kg/m³ |

| Consistency index | K | 20.6 | Pa·sn |

| Flow behavior index | n | 0.605 | – |

| Yield stress | τ0 | 650 | Pa |

| Critical shear rate | γ̇0 | 32 | s-1 |

The CFD simulation domain represents the fluid region between the wave generator and flexspline. The oil film thickness varies with the rotational angle θ, from a maximum at θ = 0° to a minimum at θ = 90°. The thickness function h(θ) can be approximated based on the elliptical geometry. For an elliptical wave generator, the film thickness as a function of angular position is given by:

$$ h(θ) = \frac{a_1 b_1}{\sqrt{a_1^2 \sin^2 θ + b_1^2 \cos^2 θ}} – \frac{a_2 b_2}{\sqrt{a_2^2 \sin^2 θ + b_2^2 \cos^2 θ}} $$

However, for simplicity in CFD setup, we used a direct 3D model with specified boundaries. The wave generator rotates at speed n1, while the flexspline rotates in the opposite direction at n1/i, where i is the transmission ratio of the strain wave gear. The boundary conditions were set as pressure inlet and outlet at gauge pressure zero, corresponding to the locations of maximum film thickness at θ = 0° and θ = 180°.

We simulated lubricant leakage from the side openings of this film region at various wave generator speeds. The leakage rate Qleak as a function of speed n1 is shown in Figure 2 of the original text, but here we summarize the trend: for speeds above 5000 rpm, leakage increases linearly with speed. Based on typical operational ranges for strain wave gear drives in high-performance applications, we selected a design speed of 10000 rpm. At this speed, the leakage rate serves as the minimum required output flow rate for our active lubrication system. This ensures that the system can compensate for lubricant loss during operation, maintaining an adequate film in the strain wave gear meshing zone.

The core of our active lubrication system is a vane-type pump integrated into the strain wave gear assembly. This pump features a single vane within a cycloidal-shaped cavity, as illustrated in Figure 3 of the original text. The cavity design ensures that as the vane rotates, the chamber volume changes, drawing lubricant in at the inlet and expelling it at the outlet. The pump is driven directly by the input shaft of the strain wave gear, ensuring synchronization with the gear operation.

The displacement per revolution of the vane pump is crucial for matching the lubricant leakage. The volumetric displacement Q per revolution can be derived from the geometry of the cavity. The cavity inner wall follows a limacon curve, with polar radius ρ given by:

$$ ρ = R + e \cos θ $$

where R is the base radius of the cavity, e is the eccentricity, and θ is the angle. In our design, we use a specific limacon with ρ = 10 + 1.5 cos θ mm. The maximum chamber volume occurs when the vane is at θ = 90°. The volume Vmax for one chamber is calculated by integrating the area swept by the vane. For a cavity with axial length l, the maximum volume is:

$$ V_{\text{max}} = l \left[ \frac{1}{2} \int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2} ρ^2 dθ – \frac{1}{2} π r^2 – \frac{1}{2} (2R – 2r) s \right] $$

where r is the radius of the drive shaft, s is the thickness of the vane, and the integral represents the area of the cavity segment. Since the pump has two pumping actions per revolution (due to the single vane design), the total displacement per revolution Q is:

$$ Q = n l \left[ R^2 \epsilon (4 – \epsilon^2) \pi + 2\pi – (2R – 2r) s \right] $$

where ε = e/R is the relative eccentricity, and n is the number of revolutions per unit time (speed). For our design, we set parameters to achieve the required flow rate at 10000 rpm. Based on the CFD leakage data and structural constraints of the strain wave gear, we determined the values listed in Table 3.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cavity axial length | l | 25 | mm |

| Cavity base radius | R | 10 | mm |

| Relative eccentricity | ε | 0.15 | – |

| Drive shaft radius | r | 8.5 | mm |

| Vane thickness | s | 4 | mm |

| Design speed | n | 10000 | rpm |

With these parameters, the pump displacement Q can be calculated to ensure it exceeds the leakage rate at the design speed, guaranteeing sufficient lubricant supply to the strain wave gear meshing interface.

Next, we performed a force analysis on the vane to ensure structural integrity under operational loads. The vane is subjected to inertial forces due to rotation, pressure differential forces from the pumping action, and frictional forces from contact with the cavity walls and rotor. The inertial forces include centrifugal force, Coriolis force, and relative acceleration force. Figure 4 of the original text depicts the inertial forces acting on the vane. We denote the following:

- Fe: Centrifugal force due to牵连 acceleration.

- Fr: Force due to relative acceleration.

- Fc: Coriolis force.

- FΔp: Force due to pressure difference across the vane.

The friction coefficients are μr for vane-rotor contact and μc for vane-cavity contact. We set μr = 0.1 and μc = 0.19 based on typical material pairings. The forces generate reaction forces and frictional forces at the contacts. Using force and moment balance equations, we derived the equilibrium conditions. For instance, when the vane is at rotational angle φ = 0, the resultant force Ri from inertial components is maximum, calculated as 145 N. The frictional force due to inertia at the vane tip against the cavity wall is approximately:

$$ μ_c F_{3i} ≈ μ_c R_i = 0.19 × 145 = 27.55 \text{ N} $$

The pressure differential force FΔp contributes additional friction. Solving the balance equations, the frictional force from pressure at the vane tip is about 2 N. Thus, the total maximum frictional force at the tip is around 29.55 N. The vane experiences bending due to these forces. The maximum bending moment Mmax occurs at the vane root and is calculated as:

$$ M_{\text{max}} = (μ_c F_{3i} + μ_c F_{3g}) × (2R – 2r) + F_{Δp} × (R – r) $$

Substituting values:

$$ M_{\text{max}} = (27.55 + 2) × (20 – 17) × 10^{-3} + F_{Δp} × (10 – 8.5) × 10^{-3} $$

With FΔp estimated from the pressure differential (assumed 0.5 MPa over vane area), we compute Mmax ≈ 1.3 × 10-1 N·m. The vane has length l = 25 mm and thickness s = 4 mm, so the maximum bending stress σmax is:

$$ σ_{\text{max}} = \frac{6 M_{\text{max}}}{l s^2} = \frac{6 × 0.13}{0.025 × (0.004)^2} = 1.95 × 10^6 \text{ Pa} $$

The vane material is selected as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which has a yield strength of approximately 20.7 × 106 Pa. Since σmax is much lower than the yield strength, the vane design is safe against mechanical failure. This analysis ensures that the vane can withstand operational loads in the strain wave gear lubrication system.

The complete active lubrication system for strain wave gear drives comprises several key components: a drive shaft, top cover, pump body, base, and the vane. The drive shaft connects to the input shaft of the strain wave gear, ensuring direct drive. The assembly is illustrated in Figure 5 of the original text. The pump body contains the cycloidal cavity, and the vane is mounted on the drive shaft. As the input shaft rotates, the vane sweeps through the cavity, creating volume variations. This action reduces pressure at the inlet, drawing lubricant from a reservoir, and increases pressure at the outlet, forcing lubricant through a passage in the drive shaft toward the wave generator and flexspline meshing area. Check valves are incorporated at the inlet and outlet to ensure unidirectional flow, allowing consistent lubricant delivery even when the input shaft reverses direction, which is common in servo applications for strain wave gear mechanisms.

The integration of this vane-type pump into the strain wave gear assembly offers several advantages. First, it provides active, positive displacement lubrication independent of orientation, solving the issue of lubricant starvation in vertical or inclined mounts. Second, it compensates for lubricant leakage dynamically, maintaining optimal film thickness in the meshing zone. Third, its compact design aligns with the miniaturization trend in strain wave gear applications. Finally, the use of a single vane and limacon cavity simplifies construction while ensuring reliable performance.

To further validate the design, we can consider performance metrics. The pump’s flow rate Q should match or exceed the leakage rate Lleak at the operating speed. From CFD, Lleak at 10000 rpm is approximately 0.05 L/min. Using our pump formula with the parameters in Table 3, we compute Q. First, calculate the eccentricity e = εR = 0.15 × 10 = 1.5 mm. The term R²ε(4 – ε²)π = 100 × 0.15 × (4 – 0.0225) × π ≈ 100 × 0.15 × 3.9775 × 3.1416 ≈ 187.5 mm². Then, 2π ≈ 6.283, and (2R – 2r)s = (20 – 17) × 4 = 12 mm². So, the expression in brackets is approximately 187.5 + 6.283 – 12 = 181.783 mm². With l = 25 mm and n = 10000 rpm = 166.67 rev/s, the displacement per second is Q = 166.67 × 25 × 181.783 × 10-9 m³/s ≈ 0.000757 m³/s = 0.757 L/s, which is far above the leakage rate. This indicates the pump is highly capable, but in practice, we might adjust parameters to optimize size and power consumption. However, for safety and to account for efficiency losses, this over-capacity is beneficial.

Moreover, the rheology of the lubricant is crucial for strain wave gear performance. The Herschel-Bulkley model captures the shear-thinning behavior of grease. The shear stress τ is given by:

$$ τ = τ_0 + K \dot{γ}^n $$

where τ0 is the yield stress, K is the consistency index, n is the flow index, and γ̇ is the shear rate. In the thin film of the strain wave gear, shear rates can be high, affecting viscosity and leakage. Our CFD analysis incorporated this model to accurately predict leakage rates. The results show that at higher speeds, the lubricant thins, leading to increased leakage but also reduced pumping power requirements.

In terms of system dynamics, the active lubrication pump must operate smoothly without introducing significant vibration or power loss. The vane’s motion within the cavity can be analyzed kinematically. The angular position of the vane φ relates to the volume V(φ) of the pumping chamber. For a limacon cavity with ρ = R + e cos θ, and with the vane aligned radially, the chamber volume as a function of φ can be derived. This allows us to model the flow ripple and pressure pulses, which should be minimized to ensure steady lubricant supply to the strain wave gear. The flow rate variation ΔQ can be expressed as:

$$ ΔQ = \frac{dV}{dφ} \frac{dφ}{dt} $$

By optimizing the cavity profile, we can reduce dV/dφ variations, leading to smoother flow. This is particularly important for precision strain wave gear applications where consistent lubrication is key to maintaining low friction and high positional accuracy.

Another aspect is thermal management. The pumping action and shear in the lubricant generate heat, which can affect lubricant viscosity and strain wave gear performance. The temperature rise ΔT in the lubricant can be estimated from the power dissipation Pdiss due to viscous shear and pumping work. For a Newtonian approximation, the shear power in the film is:

$$ P_{\text{shear}} = ∫ τ \dot{γ} dV $$

Using the Herschel-Bulkley model, this becomes more complex. However, in our design, the active lubrication system may help in heat dissipation by circulating cooler lubricant from the reservoir. This can enhance the thermal stability of the strain wave gear system.

In conclusion, we have designed a vane-type active lubrication system specifically for strain wave gear drives. The system addresses the lubrication challenges in vertical or complex orientations by actively pumping lubricant to the critical meshing interfaces. Through CFD analysis, we determined the lubricant leakage characteristics and set the design parameters for the pump. The vane pump, with a limacon cavity, provides sufficient displacement to compensate for leakage at high speeds. Force analysis confirmed the structural integrity of the vane. The integrated design ensures unidirectional lubricant flow regardless of input shaft rotation direction, making it suitable for dynamic servo applications. This active lubrication approach enhances the reliability and longevity of strain wave gear mechanisms, supporting their use in advanced robotics and precision machinery. Future work may involve prototyping and experimental validation under various operating conditions to optimize performance further.

The strain wave gear technology continues to evolve, and innovations in lubrication like this vane-type system contribute to its advancement. By ensuring continuous and effective lubrication, we can unlock higher performance and durability for strain wave gear applications in demanding environments. The integration of such active systems represents a step forward in the design of maintenance-friendly and robust transmission systems for the next generation of mechanical assemblies.