In the field of precision mechanical transmission, the strain wave gear, also known as harmonic drive, has emerged as a critical component for applications requiring high reduction ratios, compactness, and accuracy. As a researcher focused on advancing gear technology, I have investigated the limitations of traditional strain wave gear designs, particularly issues like tooth interference and uneven stress distribution. To address these, I developed a short-tooth biarc tooth profile for strain wave gears, which offers improved load capacity and smoother operation. However, manufacturing such complex profiles poses significant challenges, often leading to suboptimal meshing in practical applications. Therefore, in this work, I propose a method for designing and optimizing cutting tools using the tooth profile normal method, followed by virtual machining simulations to guide actual production. This approach significantly enhances the success rate of manufacturing short-tooth biarc strain wave gears, and I validate its feasibility through theoretical design and case studies. The integration of virtual reality techniques into the machining process represents a substantial step forward in realizing high-performance strain wave gear systems.

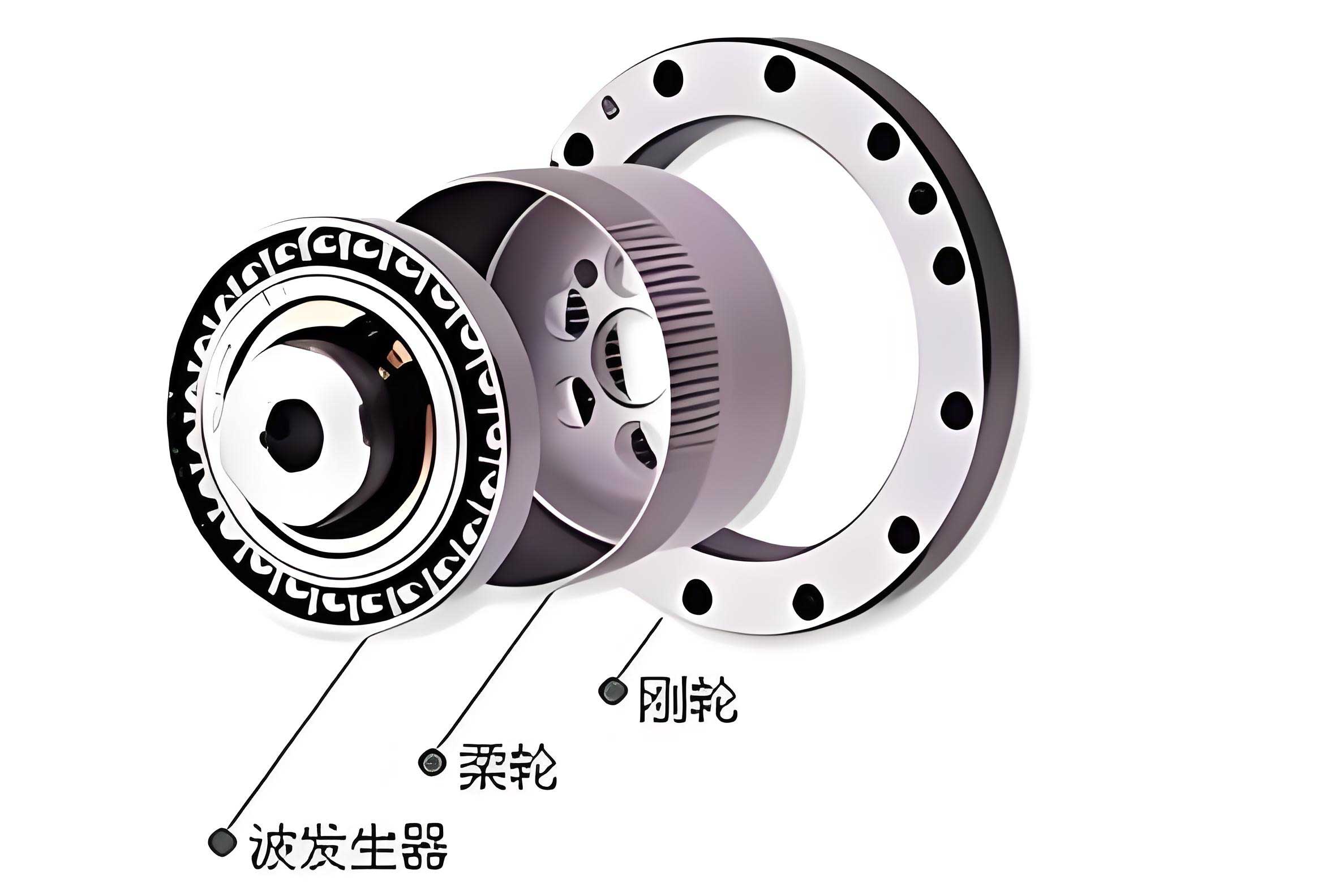

The strain wave gear mechanism relies on the elastic deformation of a flexible spline (flexspline) meshing with a rigid circular spline (circular spline) via a wave generator. This unique principle allows for advantages such as high torque capacity, near-zero backlash, and compact design. However, traditional tooth profiles, like the involute, can suffer from stress concentration and interference during meshing, especially under heavy loads or high precision demands. The short-tooth biarc profile, with its multi-segment circular arcs, mitigates these issues by providing a more uniform stress distribution and reduced tooth height, thereby minimizing the risk of jamming and improving durability. My research focuses on overcoming the manufacturing hurdles associated with this advanced profile, ensuring that the theoretical benefits translate into reliable real-world performance.

To understand the design process, it is essential to first analyze the tooth profile geometry of the short-tooth biarc strain wave gear. The flexspline and circular spline have distinct profiles composed of several circular arcs, each serving a specific function to enhance meshing. For the flexspline, which is the deformable component in the strain wave gear system, I established a coordinate system with its center as the origin. The single-side tooth profile consists of five arc segments: the tip arc, upper arc, connection arc, lower arc, and root arc. These segments are mathematically defined to ensure smooth transitions and optimal contact conditions. The equations for the flexspline profile are as follows:

Tip arc segment (AB): $$x^2 + \left(y – \frac{m z}{2} + h_f\right)^2 = \left(\frac{m z}{2}\right)^2$$

Upper arc segment (BC): $$\left(x – \frac{\xi m}{2} + \rho_a\right)^2 + (y – h_s)^2 = \rho_a^2$$

Connection arc segment (CD): $$\left(x – l_b – \frac{\xi m}{2}\right)^2 + (y + h_a – h_b)^2 = \rho_b^2$$

Lower arc segment (DE): $$(x – l_c)^2 + (y – h_c)^2 = \rho_c^2$$

Root arc segment (EF): $$x^2 + (y + \rho_d – h_f)^2 = \rho_d^2$$

Here, \(m\) is the module, \(z\) is the number of teeth, and \(h_f\), \(h_s\), \(h_a\), \(h_b\), \(h_c\), \(\rho_a\), \(\rho_b\), \(\rho_c\), \(\rho_d\), \(l_b\), \(l_c\), and \(\xi\) are design parameters specific to the short-tooth biarc profile. This multi-arc structure reduces stress peaks, a common issue in conventional strain wave gear teeth, and the shortened tooth height prevents interference during the wave generator’s motion.

For the circular spline, which is the rigid internal gear in the strain wave gear assembly, I defined a similar but complementary profile. Using a coordinate system with the root bottom as the origin, the single-side tooth profile comprises arcs that conjugate with the flexspline profile. The equations are:

Root arc segment (A’B’): $$\left(x + \frac{\xi m}{2}\right)^2 + (y – h’_s)^2 = \rho’^{2}_a$$

Upper arc segment (B’C’): $$\left(x + \frac{\xi m}{2} + l’_b\right)^2 + (y – h’_b)^2 = \rho’^{2}_b$$

Connection arc segment (C’D’): $$\left(x – \frac{\xi m}{2} – l’_c\right)^2 + (y – h’_c)^2 = \rho’^{2}_c$$

Lower arc segment (D’E’): $$x^2 + y^2 = \rho’^{2}_d$$

Tip arc segment: $$x^2 + \left(y + \frac{m z}{2} + h_a\right)^2 = \left(\frac{m z}{2}\right)^2$$

The parameters with primes (e.g., \(h’_s\), \(\rho’_a\)) correspond to the circular spline and are designed to ensure proper meshing with the flexspline under deformation. The use of circular arcs at the tip and root regions enhances the contact pattern and stress distribution in the strain wave gear system. To summarize the key geometric parameters for both profiles, I have compiled them into a table, which aids in the design and analysis process.

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Typical Value Range (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Module | \(m\) | Basic size parameter for gear teeth | 0.3–1.0 |

| Number of Teeth (Flexspline) | \(z_f\) | Teeth count on the flexible spline | 100–200 |

| Number of Teeth (Circular Spline) | \(z_c\) | Teeth count on the circular spline | 102–202 |

| Tip Arc Radius (Flexspline) | \(\rho_a\) | Radius of the upper arc segment | 0.7–0.8 |

| Connection Arc Radius (Flexspline) | \(\rho_b\) | Radius of the transition arc | 0.4–0.6 |

| Lower Arc Radius (Flexspline) | \(\rho_c\) | Radius of the lower arc segment | 0.5–0.7 |

| Root Arc Radius (Flexspline) | \(\rho_d\) | Radius of the root arc segment | 0.3–0.5 |

| Tooth Height Reduction Factor | \(\xi\) | Parameter for short-tooth design | 0.1–0.3 |

This geometric foundation is crucial for the subsequent design of cutting tools, as the tool profiles must accurately replicate these complex shapes to produce functional strain wave gear components.

The core of my methodology lies in the design of cutting tools using the tooth profile normal method. This technique ensures that the tool and gear profiles are conjugate, meaning they generate each other correctly during machining. For the circular spline, which is an internal gear, I designed an internal插齿刀 (pinion cutter), while for the flexspline, an external gear, I developed a rack-type tool (essentially a滚刀 or hob) based on the same principle. The tooth profile normal method involves calculating the normal lines at various points on the gear tooth profile and transforming coordinates to derive the corresponding tool profile.

Considering the circular spline first, let the tooth profile in its coordinate system be represented by \(y = f(x)\), which is a piecewise function due to the multiple arcs. During meshing in a strain wave gear, the flexspline deforms elliptically, and its pitch curve rolls without slip against the circular spline’s pitch curve. To avoid interference, the circular pitch must match, allowing determination of the modification coefficient. For the pinion cutter design, I avoid undercutting by applying a shift modification. At any point \(M(x_1, y_1)\) on the circular spline profile, the angle \(\alpha\) between the tangent and the x-axis is computed. Through coordinate transformations accounting for the relative motion between the gear and cutter, the contact condition yields the tool profile coordinates. The transformation matrix is:

$$\begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ y_1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\phi_1 – \phi_2) & -\sin(\phi_1 – \phi_2) & -a \sin(\phi_2) \\ \sin(\phi_1 – \phi_2) & \cos(\phi_1 – \phi_2) & -a \cos(\phi_2) \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x \\ y \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}$$

where \(\phi_1 = \frac{\pi}{2} – (\alpha + \phi)\), \(\phi\) is derived from \(\cos \phi = \frac{x_1 \cos \alpha + y_1 \sin \alpha}{r}\), \(r = a \cdot \frac{z_g}{z_g – z_d}\) is the pitch radius of the circular spline, \(a\) is the center distance between the circular spline and cutter, \(z_g\) is the number of teeth on the circular spline, and \(z_d\) is the number of teeth on the cutter. \(\phi_2\) is the rotation angle of the cutter when point \(M\) becomes a contact point. This transformation maps the circular spline profile to the cutter profile, ensuring conjugacy.

For the flexspline, which is an external gear, the tool design follows a similar approach but with a rack-type tool due to its external meshing nature. The coordinate transformation for deriving the rack tool profile from the flexspline profile is:

$$\begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ y_1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos \phi_2 & \sin \phi_2 & r_2 (\sin \phi_2 – \phi_2 \cos \phi_2) \\ -\sin \phi_2 & \cos \phi_2 & r_2 (\cos \phi_2 + \phi_2 \sin \phi_2) \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x \\ y \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}$$

where \(r_2\) is the pitch radius of the flexspline. This rack tool profile can then be used to manufacture the flexspline via hobbing or shaping processes. During design, I paid special attention to several critical aspects: first, the piecewise nature of the profiles requires smooth interpolation at segment junctions to ensure derivative continuity, which is vital for accurate tool path generation; second, since the circular spline is an internal gear, its cutter design differs from that for external gears, necessitating separate optimization routines; third, to prevent undercutting, I added a tip relief or clearance to the tool profiles, typically set to \(0.25m\), where \(m\) is the module. This clearance ensures that the generated gear teeth have proper root shapes without interference.

To validate the tool designs and simulate the manufacturing process, I conducted virtual machining using MATLAB. This approach mimics the actual cutting operations by modeling the relative motion between the tool and gear blank. For the flexspline, the simulation involves a rack tool translating and rotating relative to a gear blank. Initially, the tool translates by a distance \(S = R \phi\), where \(R\) is the pitch radius and \(\phi\) is the rotation angle, and then rotates accordingly. The transformation for any point on the tool is given by:

First, translation: $$x_1 = x – R \phi, \quad y_1 = y$$

Then, rotation: $$x_2 = R_1 \sin \phi_1 + x_0, \quad y_2 = R_1 \cos \phi_1 + y_0$$

where \(R_1 = \sqrt{(x_1 – x_0)^2 + (y_1 – y_0)^2}\), \(\phi_1 = \phi_0 – \phi\), and \(\phi_0 = \arctan\left(\frac{x_1 – x_0}{y_1 – y_0}\right)\).

Similarly, for the circular spline, I simulated the action of an internal pinion cutter meshing with a gear blank. These simulations allow me to visualize the generation of the tooth profiles and identify any potential issues, such as profile errors or undercutting, before physical manufacturing. The virtual machining process is integral to improving the success rate of producing high-quality strain wave gear components, as it provides a digital twin of the cutting operation.

To demonstrate the practical application, I selected a case study with specific parameters: a strain wave gear set with a circular spline tooth count \(z_c = 162\), a flexspline tooth count \(z_f = 160\), and a module \(m = 0.5\) mm. Using the geometric models described earlier, I derived the tooth profiles for both components. The flexspline profile features arc radii such as \(\rho_a = 0.760\) mm and \(\rho_c = 0.500\) mm, while the circular spline has corresponding radii \(\rho’_a = 0.737\) mm and \(\rho’_c = 0.494\) mm. The slight differences are due to the deformation of the flexspline during operation, ensuring conjugate meshing in the strain wave gear system. The connection arcs (e.g., \(\rho_b\) and \(\rho’_b\)) provide smooth transitions, reducing stress concentration—a key advantage for the durability of strain wave gears.

Based on these profiles, I designed the cutting tools. For the circular spline, I created a pinion cutter with 100 teeth, incorporating a tip clearance to avoid undercutting. For the flexspline, I designed a rack-type tool equivalent to a hob. The tool profiles were optimized using the tooth profile normal method, and the results are summarized in the table below, which compares key tool parameters with the gear parameters.

| Tool Type | Number of Teeth/Cutter Profile | Key Design Parameters | Clearance Added |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular Spline Cutter (Pinion) | 100 teeth | Based on circular spline profile with transformation matrix | 0.25m = 0.125 mm |

| Flexspline Tool (Rack/Hob) | Rack profile conjugate to flexspline | Derived from flexspline profile using rack transformation | 0.25m = 0.125 mm |

I then performed virtual machining simulations in MATLAB. For the circular spline, the simulation showed that the generated tooth profile matched the theoretical design perfectly, confirming the correctness of the cutter design. Similarly, for the flexspline, the rack tool simulation produced accurate teeth without errors. The virtual machining process effectively predicted the manufacturing outcome, demonstrating that the tools can produce the desired short-tooth biarc profiles for strain wave gears. This validation is crucial because it minimizes trial-and-error in actual production, saving time and resources while ensuring high precision.

The benefits of this approach extend beyond mere profile accuracy. By using virtual machining, I can analyze the meshing behavior of the manufactured strain wave gear under load, predict stress distributions, and optimize the profiles further if needed. For instance, the short-tooth design reduces tooth height, which decreases bending stresses and enhances the load capacity of the strain wave gear. Moreover, the multi-arc structure distributes contact forces more evenly, leading to smoother operation and longer service life. These advantages make the short-tooth biarc strain wave gear particularly suitable for demanding applications like robotics, aerospace, and precision machinery, where reliability and performance are paramount.

In terms of implementation, the tooth profile normal method proved robust for designing complex tool geometries. However, I encountered challenges such as ensuring numerical stability at profile junctions and handling the piecewise functions in MATLAB. To address this, I used spline interpolation to smooth the transitions, ensuring that the tool paths were continuous and differentiable. Additionally, the virtual machining simulations required careful setting of simulation parameters, such as step sizes for tool motion, to avoid discretization errors. These practical insights are valuable for engineers looking to adopt similar methods for manufacturing advanced strain wave gear systems.

Looking forward, the integration of virtual reality and digital twin technologies into gear manufacturing holds great promise. By combining the tooth profile normal method with advanced simulation platforms, we can create comprehensive virtual prototypes of strain wave gears, testing them under various operating conditions before physical production. This not only improves manufacturing success rates but also accelerates the development cycle for new gear designs. Furthermore, as additive manufacturing techniques evolve, the ability to produce complex tool geometries directly from digital models could revolutionize the production of strain wave gear components, making them more accessible and cost-effective.

In conclusion, my research presents a systematic approach to designing and simulating cutting tools for short-tooth biarc strain wave gears. Through detailed geometric modeling, application of the tooth profile normal method, and virtual machining validation, I have demonstrated that this method significantly enhances manufacturing accuracy and efficiency. The case study with specific parameters confirms the feasibility, and the resulting strain wave gear prototypes exhibit improved performance characteristics. This work contributes to the ongoing advancement of strain wave gear technology, offering a practical solution to manufacturing challenges and paving the way for more reliable and high-performance transmission systems in various industrial applications. The repeated emphasis on strain wave gear throughout this paper underscores its importance as a key innovation in mechanical engineering, and I believe that continued research in this area will yield even greater benefits for future technologies.