In my extensive research and practical experience with precision transmission systems, I have dedicated significant effort to advancing the design and manufacturing of strain wave gears. These gears, also known as harmonic drives, are renowned for their compact size, high reduction ratios, and exceptional accuracy. The core principle of a strain wave gear relies on the elastic deformation of a flexible component, typically called the flexspline, which engages with a rigid circular spline via a wave generator. This unique mechanism allows for smooth motion transmission with minimal backlash, making strain wave gears indispensable in robotics, aerospace, and high-precision industrial applications. However, traditional steel-based strain wave gears face challenges related to material costs, manufacturing complexity, and weight. In my work, I have explored the substitution of steel with engineering thermoplastics, which offer advantages such as reduced weight, inherent lubricity, lower production costs, and excellent fatigue resistance relative to their elastic modulus. This article details my comprehensive approach to designing a plastic flexspline for a strain wave gear reducer and the corresponding injection mold, leveraging computer-aided engineering (CAE) for validation and optimization.

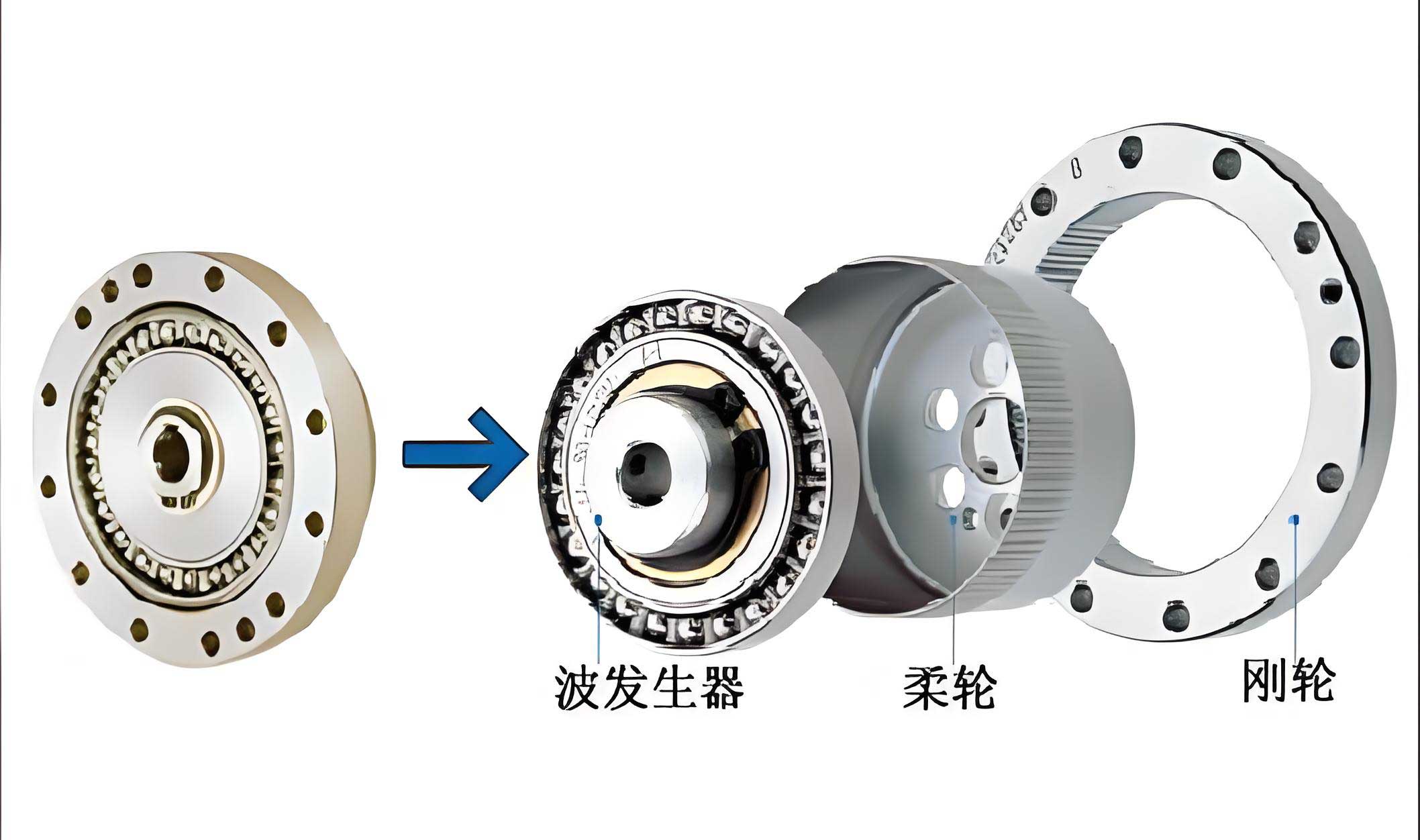

The fundamental configuration of a strain wave gear comprises three primary elements: the circular spline (a rigid internal gear), the flexspline (a thin-walled, flexible external gear), and the wave generator (an elliptical or cam-type component that deforms the flexspline). During operation, the wave generator induces a controlled elliptical deflection in the flexspline, causing its teeth to engage with those of the circular spline at two diametrically opposite regions. As the wave generator rotates, this engagement zone propagates, resulting in a relative motion between the flexspline and circular spline. The reduction ratio is determined by the difference in tooth counts between the two splines. A critical advantage of the strain wave gear is its ability to achieve high reduction ratios in a single stage, often exceeding 100:1, with exceptional torsional stiffness and positional accuracy. My focus has been on optimizing the flexspline, as it is the most critical and dynamically stressed component, undergoing cyclic elastic deformation during service.

Selecting the appropriate material for the plastic strain wave gear flexspline is paramount. After evaluating various engineering thermoplastics, I chose Polyamide 66 (PA66) for this application. PA66 exhibits an excellent balance of mechanical properties, including high tensile strength, good fatigue endurance, and resilience. It maintains performance at elevated temperatures—crucial for operational environments up to 60°C—and has a favorable elastic modulus that allows for the necessary flexible deformation without permanent set. Furthermore, its wear resistance and low friction coefficient are beneficial for gear operation. The molding shrinkage of PA66, typically around 1.5%, must be meticulously accounted for in the mold design to ensure dimensional fidelity of the final strain wave gear component.

The design of the flexspline begins with defining its key geometric parameters based on the transmission requirements. For the target application, the specifications included a transmission ratio of 100, a wave number of 2, an input speed of 3000 rpm, an output torque of 500 N·m, and a service life of 3000 hours. The transmission scheme involves a fixed circular spline and a cup-type flexspline as the output element, driven by an eccentric disk wave generator. The primary dimensions—the pitch diameter, tooth number, and wave generator characteristics—are derived from torque capacity charts and standard gear design principles for strain wave gears. To compensate for the lower modulus of plastic compared to steel, the wall thickness of the plastic flexspline is typically increased. In my design, the wall thickness was set to approximately twice that of an equivalent metal flexspline to ensure sufficient structural integrity under load.

The tooth profile for the strain wave gear flexspline requires careful calculation. I employed a modified involute profile suitable for the deformation conditions. The key geometric parameters are calculated using the following fundamental gear equations and relationships specific to strain wave gearing. The module (m) is a fundamental parameter derived from the pitch diameter (d) and tooth count (z):

$$m = \frac{d}{z}$$

For the designed flexspline with a pitch diameter of 150 mm and 200 teeth, the module is:

$$m = \frac{150 \text{ mm}}{200} = 0.75 \text{ mm}$$

The pressure angle (α) for strain wave gears is often modified to optimize contact and stress distribution. In this design, a pressure angle of 29.2° was selected. The tooth addendum (h_a) and dedendum (h_f) are calculated as multiples of the module, with specific coefficients to account for the flexible meshing conditions:

$$h_a = k_a \cdot m$$

$$h_f = k_f \cdot m$$

where $k_a$ and $k_f$ are the addendum and dedendum coefficients, respectively. For this application, $k_a$ was 0.6563 and $k_f$ was 0.8437. The clearance (c) is given by:

$$c = k_c \cdot m = 0.1875 \cdot m$$

The complete set of geometric parameters for the plastic flexspline tooth profile is summarized in the table below.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (mm) | Calculation Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Module | m | 0.75 | $m = d / z$ |

| Pressure Angle | α | 29.2° | Optimized for strain wave contact |

| Addendum | $h_a$ | 0.4922 | $h_a = 0.6563 \times m$ |

| Dedendum | $h_f$ | 0.6328 | $h_f = 0.8437 \times m$ |

| Clearance | c | 0.1406 | $c = 0.1875 \times m$ |

| Pitch Diameter | d | 150.0 | Specified based on torque capacity |

| Tooth Count | z | 200 | Determined by transmission ratio ($i = z / (z – z_f)$) |

| Wall Thickness | t | 3.0 | Approx. 2x metal equivalent for strength |

The overall structure of the cup-type flexspline was modeled in 3D CAD software, featuring a cylindrical body with external teeth, a mounting flange with bolt holes, and a reinforced rim to manage stress concentrations. The total height of the flexspline component was 142.5 mm. The successful operation of a strain wave gear heavily depends on the precise geometry and elastic behavior of this flexspline.

Transitioning to manufacturing, injection molding was selected as the production method for the plastic strain wave gear flexspline due to its suitability for high-volume, cost-effective production of complex plastic parts. The mold design is critical to achieving the required dimensional accuracy and minimizing residual stresses that could affect the gear’s performance. My mold design philosophy centered on ensuring uniform filling, efficient cooling, and minimal deformation during ejection.

The mold is a two-plate cold runner system with a single cavity per mold half (1×1 layout, though multi-cavity is possible). The parting surface was placed at the largest peripheral contour of the flexspline, which is at the open end of the cup shape. This simplifies mold construction and facilitates part ejection. Since the flexspline flange contains six mounting holes, these are formed by incorporated inserts in the mold core. This approach enhances manufacturability and improves venting in these areas to avoid air traps.

The gating system is a critical aspect. I designed a side gate with a circular cross-section to feed material into the cavity. The gate land length is 2 mm with a diameter of 1 mm. The runner system uses a full-round runner with a diameter of 7 mm and a length of 32 mm. A Z-shaped cold slug well with a diameter of 10 mm is included at the end of the main runner to trap the initial cold material. To validate this design, I performed a filling analysis using CAE software. The results confirmed that the cavity fills completely without significant hesitation or weld lines, ensuring a homogeneous part. The following table outlines the key gating system parameters.

| Component | Feature | Dimension/Type |

|---|---|---|

| Gate | Type | Circular Side Gate |

| Land Length | 2.0 mm | |

| Diameter | 1.0 mm | |

| Runner | Shape | Full Round |

| Diameter | 7.0 mm | |

| Cold Slug Well | Type | Z-Shaped |

| Diameter | 10.0 mm |

The ejection system must remove the part without causing distortion. Given the cup shape of the strain wave gear flexspline, I employed a pattern of cylindrical ejector pins. Five pins are used per cavity: one central pin and four peripheral pins arranged symmetrically. Each pin has a diameter of 12 mm. The ejection stroke is calculated as the part height plus a safety margin. For a part height of 142.5 mm, the stroke was set to 160 mm to ensure complete release. The ejection force required can be estimated considering the shrinkage of PA66 on the core. The theoretical holding pressure ($P_h$) and ejection force ($F_e$) can be related by:

$$F_e = \mu \cdot P_h \cdot A_c$$

where $\mu$ is the coefficient of friction between the plastic and mold steel, $P_h$ is the residual pressure on the core, and $A_c$ is the contact area between the part and the core. For this design, the pin arrangement provides sufficient force distribution to prevent marking or bending of the thin-walled flexspline.

Perhaps the most crucial system in the mold for a precision part like a strain wave gear component is the cooling system. Non-uniform cooling can lead to warpage, residual stresses, and dimensional inaccuracies, particularly in the critical inner diameter of the flexspline where engagement with the wave generator occurs. My cooling circuit design aims for maximum uniformity and efficiency. In the fixed mold half (cavity side), a combination of straight-through channels and a serial layout is used. The channels have a diameter of 8 mm and a pitch of 40 mm. In the moving mold half (core side), which cools the inner surface of the flexspline cup, a dual-circuit layout with channels running longitudinally is implemented. The distance from the channel center to the core surface is maintained at 43 mm to ensure effective heat extraction. The cooling time ($t_c$) can be estimated using the formula for plate cooling:

$$t_c \approx \frac{s^2}{\pi \cdot \alpha} \cdot \ln\left(\frac{8}{\pi^2} \cdot \frac{T_m – T_w}{T_e – T_w}\right)$$

where $s$ is the wall thickness, $\alpha$ is the thermal diffusivity of the plastic, $T_m$ is the melt temperature, $T_w$ is the mold wall temperature, and $T_e$ is the ejection temperature. For PA66 with a wall thickness of 3 mm, the calculated cooling time is within the cycle time constraints. CAE cooling analysis confirmed that this design maintains temperature variation across the part within acceptable limits, resulting in a predicted deformation of the flexspline’s inner diameter of less than 0.3 mm, which meets the tight tolerance requirement for proper strain wave gear operation.

The complete mold assembly incorporates standard components: the clamp plate, cavity plate, core plate, ejector plate, support blocks, and guiding elements. The mold base is designed for compatibility with a standard injection molding machine. The injection process begins with molten PA66 being injected through the sprue, runner, and gate into the cavity. After packing and holding phases, coolant circulates through the designed channels to solidify the part. Once cooled, the mold opens, and the ejector system advances to push the strain wave gear flexspline off the core. The molded part then undergoes minimal post-processing before assembly into the strain wave gear reducer.

To further illustrate the design relationships and performance metrics, I have developed several key formulas that govern the behavior and manufacturing of plastic strain wave gears. The transmission ratio ($i$) of a strain wave gear with a fixed circular spline is given by:

$$i = -\frac{z_f}{z_c – z_f}$$

where $z_f$ is the number of teeth on the flexspline and $z_c$ is the number of teeth on the circular spline. The negative sign indicates direction reversal. For a design with $z_f = 200$ and $z_c = 202$ (a common configuration for a 100:1 ratio), we have:

$$i = -\frac{200}{202 – 200} = -100$$

The bending stress ($\sigma_b$) in the flexspline tooth root is a critical design parameter and can be approximated using Lewis formula adapted for flexible gears:

$$\sigma_b = \frac{F_t}{m \cdot b \cdot Y} \cdot K_a \cdot K_v \cdot K_m$$

where $F_t$ is the tangential tooth load, $b$ is the face width, $Y$ is the Lewis form factor (modified for the tooth profile), and $K_a$, $K_v$, $K_m$ are application, velocity, and mounting factors, respectively. For plastic gears, a fatigue strength ($\sigma_{fat}$) check against this stress is essential. The tangential load relates to output torque ($M$) and pitch radius ($r$):

$$F_t = \frac{M}{r}$$

Another vital aspect is the radial deflection ($\delta_r$) of the flexspline under the influence of the wave generator, which is central to the operation of the strain wave gear. This can be modeled considering the flexspline as a thin-walled cylinder:

$$\delta_r \approx \frac{p \cdot r^3}{E \cdot I}$$

where $p$ is the distributed pressure from the wave generator, $E$ is the elastic modulus of the plastic, and $I$ is the area moment of inertia of the flexspline wall cross-section. Ensuring this deflection is within elastic limits and provides proper tooth engagement is key.

Injection molding parameters also play a role in final part quality. The required injection pressure ($P_{inj}$) to fill the cavity can be described by a simplified Bernoulli’s equation modified for non-Newtonian flow:

$$P_{inj} \approx \Delta P_{runner} + \Delta P_{gate} + \Delta P_{cavity}$$

$$\Delta P_{cavity} \propto \frac{12 \cdot \eta \cdot L \cdot Q}{w \cdot h^3}$$

where $\eta$ is the melt viscosity, $L$ is flow length, $Q$ is volumetric flow rate, and $w$ and $h$ are the cavity width and thickness. Optimizing these parameters minimizes residual stresses.

The following table provides a comparative summary of key properties between traditional steel and the selected engineering plastic (PA66) for strain wave gear flexsplines, highlighting the rationale for material substitution.

| Property | Steel (Typical Alloy) | PA66 (Glass-Filled) | Implication for Strain Wave Gear Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | 7.85 | 1.45 | Significant weight reduction (~80%) with plastic. |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 500-1000 | 80-120 | Lower strength necessitates thicker sections in plastic design. |

| Elastic Modulus (GPa) | 200 | 2.8-3.0 | Much lower stiffness allows larger elastic deformation, beneficial for flexspline function. |

| Fatigue Endurance Limit (MPa) | 200-400 | 25-35 | Lower but sufficient for many applications when designed appropriately. |

| Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | 50 | 0.25 | Plastic is an insulator, requiring efficient mold cooling. |

| Coefficient of Friction | 0.1-0.3 (lubricated) | 0.2-0.4 (dry) | Plastic can run with less or no lubrication, simplifying maintenance. |

| Manufacturing Cost | High (machining, finishing) | Low (injection molding) | Molding enables complex geometries at low unit cost for high volumes. |

My validation process heavily relied on CAE simulations beyond filling analysis. Structural finite element analysis (FEA) was conducted on the 3D model of the plastic flexspline to assess stress distribution under load. The analysis applied the torque and the deformation induced by the wave generator. The results indicated that the maximum von Mises stress in the plastic flexspline remained well below the yield strength of PA66, with a safety factor greater than 2. The deformation pattern confirmed that the elliptical deflection required for strain wave gear operation was achieved without over-stressing critical areas like the tooth roots or the rim. Furthermore, modal analysis was performed to ensure the natural frequencies of the flexspline were sufficiently distant from the operating frequency to avoid resonance, which could lead to premature fatigue failure in the strain wave gear assembly.

The design of the strain wave gear assembly also considers the interaction between the plastic flexspline and the other metal components (circular spline and wave generator). The difference in thermal expansion coefficients between plastic and metal must be accounted for to maintain proper clearance and interference under varying temperatures. The diametral clearance ($C_d$) at assembly temperature ($T_a$) and its change at operating temperature ($T_o$) can be expressed as:

$$C_d(T) = D_c(T) – D_f(T)$$

$$D_f(T) = D_{f0} \cdot [1 + \alpha_f \cdot (T – T_a)]$$

$$D_c(T) = D_{c0} \cdot [1 + \alpha_c \cdot (T – T_a)]$$

where $D_{f0}$ and $D_{c0}$ are the diameters of flexspline and circular spline at assembly, and $\alpha_f$ and $\alpha_c$ are their coefficients of thermal expansion. For reliable operation of the strain wave gear, $C_d$ must remain within a specified range across the temperature spectrum.

In conclusion, my comprehensive design and analysis demonstrate the viability of using engineering plastics for manufacturing strain wave gear flexsplines. The process involves meticulous geometric design tailored to the unique demands of elastic gear meshing, careful material selection, and a robust injection mold design validated through CAE tools. The plastic strain wave gear offers compelling advantages in weight, cost, and performance for suitable applications. The mold design, with its optimized gating, cooling, and ejection systems, ensures the production of precise and reliable flexspline components. This approach paves the way for broader adoption of polymer-based strain wave gears in industries where lightweight, corrosion-resistant, and economically produced precision reducers are increasingly demanded. Future work may explore advanced composites for even higher performance or additive manufacturing techniques for prototyping and low-volume production of custom strain wave gear designs.

The journey of designing a plastic strain wave gear reinforces the importance of an integrated approach, combining mechanical design principles with polymer science and advanced manufacturing engineering. As the technology evolves, the potential for innovative applications of strain wave gears continues to expand, driven by the unique benefits that engineered plastics bring to this fascinating field of precision motion control.