In the field of precision transmission systems, strain wave gears, also known as harmonic drives, play a pivotal role due to their high reduction ratios, compact design, and exceptional positional accuracy. These gears are extensively employed in aerospace, robotics, and precision instrumentation where reliable performance under load is critical. However, understanding the multi-tooth meshing behavior under various load conditions remains a complex challenge, directly influencing transmission efficiency, durability, and load capacity. This article, from my perspective as a researcher in mechanical engineering, delves into the load meshing performance of a strain wave gear featuring a novel tri-arc spatial tooth profile. Through advanced finite element analysis (FEA), I aim to unravel the distribution of meshing forces and contact pressures from no-load to the instantaneous maximum allowable torque, providing insights that can drive design improvements for enhanced load-bearing capability and stiffness.

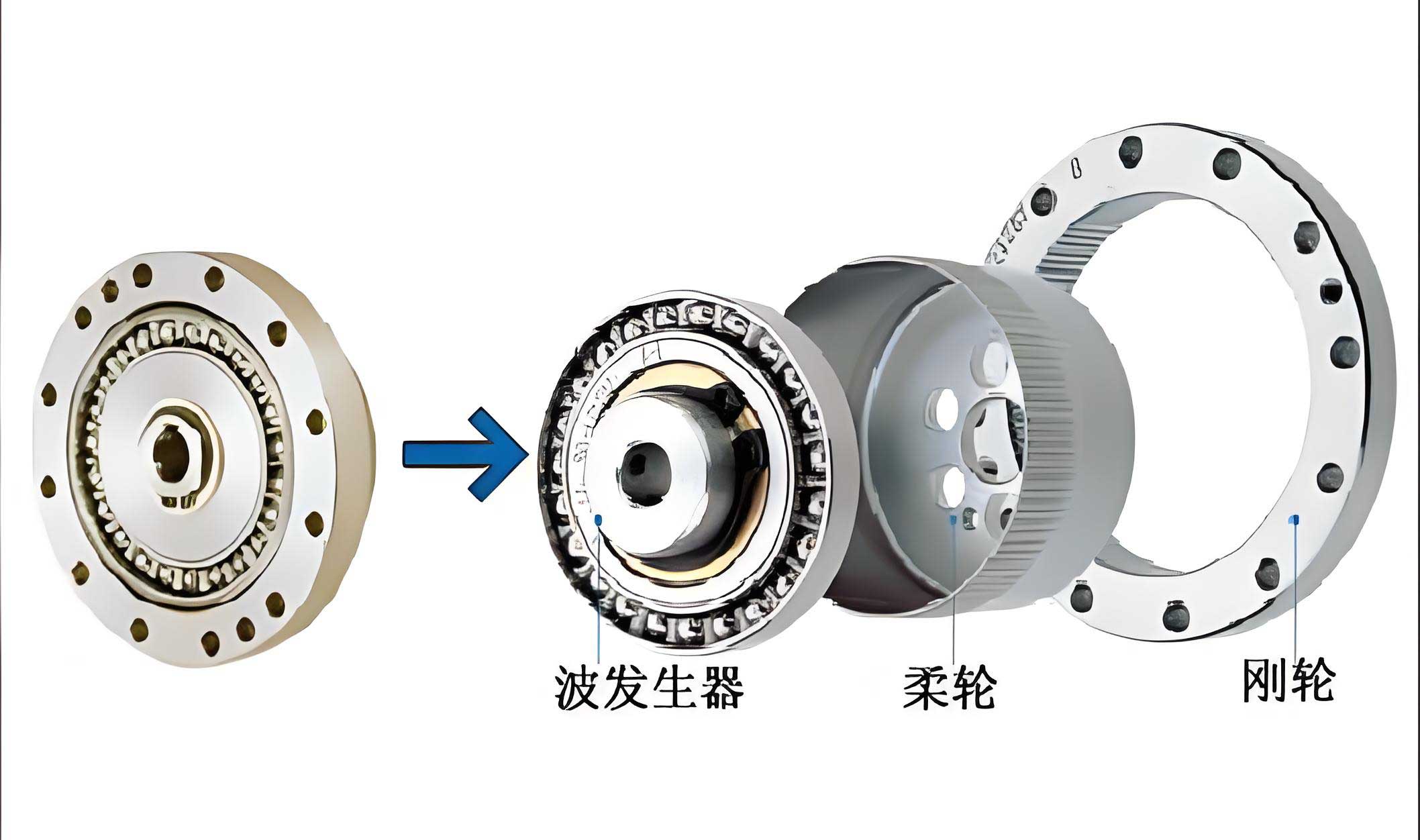

The core of a strain wave gear system consists of three primary components: a rigid circular spline, a flexible flexspline, and a wave generator. The wave generator, typically an elliptical cam, deforms the flexspline, causing its teeth to engage and disengage with those of the circular spline in a progressive wave-like motion. Traditional tooth profiles, such as involute or double-circular-arc, have been widely studied, but the tri-arc spatial profile offers potential advantages like more uniform backlash distribution, increased number of simultaneously engaged teeth, and larger contact areas. My focus is to rigorously evaluate whether these theoretical benefits translate into superior performance under practical load conditions. The load transmission in a strain wave gear is not borne by a single tooth pair but distributed across multiple teeth in the engagement zone. This distribution is highly nonlinear and influenced by factors such as the initial backlash, tooth profile geometry, radial deformation of the flexspline, and the applied torque. Consequently, accurately predicting the meshing force on each tooth and the ensuing contact pressure on the tooth surfaces is essential for preventing premature wear, pitting, and ensuring structural integrity. In this work, I establish a detailed three-dimensional solid-element finite element model that captures the intricate geometry of the tri-arc profile and the complex contact interactions.

The modeling process begins with the precise definition of the flexspline’s geometry. The cup-type flexspline, modeled in this study, comprises a thin-walled cylindrical body, a diaphragm, and a toothed ring. The tooth ring features a variable thickness achieved through radial modification along the tooth width (face width). This modification is crucial for managing the initial backlash distribution axially and preventing edge loading. The tri-arc tooth profile on the flexspline is constructed from four smoothly connected circular arcs. Let the coordinate system for the flexspline tooth profile be defined with its origin at the tooth center on the pitch circle. The profile consists of arcs defined by their radii and center coordinates. The upper flank (near the tooth tip) and lower flank (near the tooth root) are designed using specific arc segments to ensure conjugate action with the circular spline. The profile parameters can be summarized in a table for clarity.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth | \(z_f\) | 240 |

| Pitch Circle Radius | \(r_{0f}\) | 31.712 |

| Arc 1 Radius (Tip) | \(R_1\) | 0.142 |

| Arc 2 Radius | \(R_2\) | 0.793 |

| Arc 3 Radius | \(R_3\) | 0.516 |

| Arc 4 Radius (Root) | \(R_4\) | 0.132 |

| Tooth Addendum | \(h_a\) | 0.238 |

| Tooth Dedendum | \(h_f\) | 0.317 |

| Face Width | \(b\) | 10.0 |

| Radial Mod. (Front) | \(\delta_f\) | 20.053 |

| Radial Mod. (Rear) | \(\delta_b\) | 20.035 |

The circular spline, with \(z_c = 242\) teeth, possesses a conjugate tooth profile derived from the envelope of the flexspline’s motion. Its profile is also composed of circular arcs and tangent lines. The key parameters for the circular spline tooth profile are tabulated below. The design ensures that under no-load and assembled conditions, a specific initial backlash distribution is achieved, which is minimal near the major axis of the wave generator and increases gradually towards the ends of the engagement zone and along the tooth width from the middle to the rear section.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth | \(z_c\) | 242 |

| Pitch Circle Radius | \(r_{0c}\) | 31.947 |

| Arc 1 Radius (Root) | \(R_{c1}\) | 0.237 |

| Arc 2 Radius | \(R_{c2}\) | 0.410 |

| Arc 3 Radius | \(R_{c3}\) | 0.396 |

| Arc 4 Radius (Tip) | \(R_{c4}\) | 0.083 |

The finite element model is constructed using high-order 3D solid elements (SOLID186) for the flexspline to accurately capture stress and deformation. The circular spline, being significantly stiffer, is modeled as a rigid body in the contact simulations to reduce computational cost without sacrificing accuracy for the phenomena of interest. The wave generator is simplified to its elliptical contact surface and treated as an analytical rigid body. The core of the simulation setup lies in defining the contact interactions. Surface-to-surface contact pairs are established between the wave generator and the inner wall of the flexspline, and between the tooth flanks of the flexspline and circular spline. The flexspline material is assigned linear elastic properties with a Young’s modulus \(E = 210\) GPa and Poisson’s ratio \(\mu = 0.3\). The boundary conditions fix the diaphragm end of the flexspline, while a progressively increasing angular displacement is applied to the circular spline to simulate the application of load torque. This method allows for the simulation of the meshing state from no-load, through rated torque, and up to the instantaneous maximum allowable torque.

The initial backlash, a critical design parameter, is defined as the shortest distance between conjugate tooth profiles when the gear is assembled under no load. For the tri-arc spatial profile, the backlash varies both circumferentially and axially. The circumferential distribution at the middle section of the tooth width is designed to be minimal near the major axis (approximately at 3° from the axis in this model) and increases symmetrically towards the engagement boundaries. Axially, due to the radial modification of the flexspline tooth ring, the backlash is smallest at the middle section and increases towards the front and rear sections, with a more pronounced increase towards the rear. This axial variation is intended to promote a wider contact area along the tooth face under load. The theoretical no-load backlash \(b_{th}(\theta, z)\) can be expressed as a function of circumferential position \(\theta\) and axial coordinate \(z\):

$$ b_{th}(\theta, z) = b_{0}(\theta) + \Delta b(z) $$

where \(b_{0}(\theta)\) is the middle-section backlash and \(\Delta b(z)\) is the axial variation component. The FEA model’s no-load state was verified by comparing the computed backlash with the theoretical values, showing good agreement, especially at the middle section.

To investigate the load meshing performance, a series of load steps corresponding to different torque levels were analyzed. The torque values for the specific strain wave gear model (size 25, reduction ratio 120) are given below.

| Load Condition | Symbol | Torque Value (N·m) | Relative to Rated Torque |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Load | NL | 0 | 0% |

| 10% Rated | 10% RAT | 6.7 | 10% |

| 50% Rated | 50% RAT | 33.5 | 50% |

| Rated Torque | RAT | 67 | 100% |

| Average Max Torque | AVT | 108 | ~161% |

| Start/Stop Peak Torque | STT | 167 | ~249% |

| Instantaneous Max Torque | MIT | 304 | ~454% |

For each load case, the simulation solves the nonlinear contact problem iteratively. The primary outputs extracted are: 1) The total meshing force on each engaged tooth of the flexspline, resolved as the resultant force from the contact pressures on its flank. 2) The distribution of contact pressure over the surface of each engaged tooth. 3) The size and location of the contact area on each tooth. The analysis of these outputs across the load range reveals the evolution of the load-sharing mechanism in this strain wave gear.

The circumferential distribution of meshing forces at different load levels presents a clear picture of how the strain wave gear shares the load. At very low torque (10% RAT), only teeth in a narrow zone near the major axis (from about -6° to 13.5°) carry measurable load. The force distribution is roughly symmetric with a single peak near the point of minimum initial backlash. As the load increases to 50% RAT, the engagement zone expands significantly, especially towards the right side (the “mesh-in” side during rotation), covering approximately from -12° to 32°. At rated torque (RAT), the zone extends from about -16.5° to 43.5°, meaning around 30% of the flexspline’s teeth are sharing the load. A key observation is that as torque increases beyond RAT, the expansion of the engagement zone on the right side slows down, and very few additional teeth enter engagement after exceeding the STT condition. This saturation indicates that the gear’s kinematic design limits the maximum number of teeth that can be in simultaneous contact, regardless of load.

More importantly, the shape of the meshing force distribution changes with load. While at lower loads it resembles a symmetric bell curve, at higher loads it becomes distinctly asymmetric. The peak meshing force shifts from the minimum backlash point (around 3°) towards the right side. Furthermore, on the right side (approximately between 24° and 36°), the meshing forces increase at a faster rate than those on the left side, forming a plateau-like distribution at the highest loads (MIT). This plateau suggests that a group of teeth on the mesh-in side collectively bear a substantial portion of the total torque. This behavior can be attributed to the axial variation of initial backlash and stiffness. Teeth on the right side, especially towards the rear section, have a progressively smaller initial gap due to the design, allowing them to engage more firmly as the flexspline twists under load. The relationship between the applied torque \(T\) and the sum of meshing forces can be conceptually expressed as:

$$ T = r_{0f} \sum_{i=1}^{N_{eng}} F_i \cdot \cos(\beta_i) $$

where \(F_i\) is the meshing force on the \(i\)-th tooth, \(N_{eng}\) is the number of engaged teeth, \(r_{0f}\) is the flexspline pitch radius, and \(\beta_i\) is the pressure angle variation at the contact point. The simulation provides the discrete values of \(F_i\) across the engagement zone.

The contact pressure distribution on individual tooth flanks offers a microscopic view of the meshing performance. Under low load, contact initiates at discrete patches, often on the front section (near the free end) of teeth on the left side (mesh-out side) and on the middle section of teeth near the major axis. The tri-arc profile, where the flexspline’s middle arc (convex) engages with the circular spline’s corresponding concave arc segment near the major axis, results in a relatively large, uniform contact patch with lower peak pressure. This convex-concave pairing is a favorable condition for load bearing. As load increases, these contact patches grow in size and often merge. For teeth near the major axis, contact spreads axially, covering a significant portion of the face width from the front to the rear section. At the rated torque, for teeth in the central engagement zone, more than half of the tooth face width is in contact.

At the maximum simulated load (MIT), the contact pattern is extensive. Teeth on the left side (-33° to -4.5°) have contact primarily on the front and middle sections of the face. Teeth around the major axis (-1.5° to 7.5°) exhibit contact over nearly the entire face width, indicating excellent utilization of the tooth geometry. Teeth on the right side (9° to 40.5°) have contact mainly on the middle and rear sections. For teeth beyond 42°, contact recedes to the middle section only. This axial progression of the main contact zone from front-to-rear as one moves circumferentially from left to right is a direct consequence of the deliberately designed axial backlash gradient. A crucial finding is that the maximum contact pressure on any tooth typically occurs at the middle section of the face width, where the flexspline receives direct radial support from the wave generator. This location benefits from higher local stiffness, allowing it to sustain higher pressures without excessive deformation, thereby enhancing the overall load capacity of the strain wave gear.

The circumferential distribution of the maximum contact pressure (the highest pressure found on each engaged tooth) reveals a distinct pattern under high load. Instead of a single peak, the distribution shows three peaks: one on the left side (around -20°), one near the major axis, and one on the right side (around 36°). The peak on the left is associated with contact occurring primarily on the tooth’s front edge, a smaller area leading to higher pressure. The central peak is moderate due to the beneficial convex-concave contact with a large area. The peak on the right side becomes the absolute maximum at very high loads (MIT). This right-side peak corresponds to a region where engagement transitions to a convex-convex contact between the flexspline tooth tip and the circular spline tooth tip, a condition that inherently produces higher Hertzian contact stress due to smaller equivalent radius of curvature. The pressure \(p_{max}\) in such a contact can be approximated by the Hertzian formula for two cylinders:

$$ p_{max} = \sqrt{ \frac{F E^*}{\pi \rho^*} } $$

where \(F\) is the normal load per unit width, \(E^*\) is the equivalent Young’s modulus, and \(\rho^*\) is the equivalent radius of curvature. For the convex-convex tip contact, \(\rho^*\) is small, leading to high \(p_{max}\) even for moderate \(F\).

Tracking the absolute maximum contact pressure in the entire gear model against the applied torque yields an important curve. The relationship is nonlinear. Initially, for torques up to about 14% of RAT, the maximum pressure rises steeply. This corresponds to the initial take-up of backlash where only a few small contact areas exist. From 14% to nearly 300% of RAT, the pressure increase is more gradual. This plateau region, encompassing the rated and typical overload conditions, indicates robust performance where the increasing number of contact teeth and expanding contact areas effectively compensate for the rising load. Beyond this, the pressure rises steeply again, signaling the onset of severe loading conditions where the contact geometry on the mesh-in side becomes the limiting factor. This behavior underscores the importance of the tri-arc profile and axial modification in extending the safe operating range of the strain wave gear.

The number of teeth in simultaneous contact, \(N_{eng}\), is a direct measure of the gear’s load-sharing capability. For the tri-arc design, \(N_{eng}\) increases with torque but asymptotically approaches a limit. At MIT, approximately 45% of the flexspline’s teeth are engaged. The load-sharing is not equal. An effective load-sharing factor \(\xi_i\) for tooth \(i\) can be defined as the ratio of its meshing force to the average force if the total torque were shared equally among all theoretically engaged teeth. The simulation allows calculation of these factors, showing that teeth near the boundaries of the engagement zone carry less load than those near the center and the high-stiffness right-side plateau.

The axial modification of the flexspline tooth ring, leading to the spatial (three-dimensional) tooth profile, proves to be highly effective. By setting the smallest initial backlash at the middle section and allowing it to increase towards the rear, the design ensures that under load, the contact zone spreads axially. This avoids stress concentration at the tooth edges and creates a wider “load belt” across the face width. The benefits are twofold: it reduces the peak contact pressure for a given torque, and it increases the total frictional force area, which can contribute to higher torsional stiffness. The radial stiffness of the flexspline assembly plays a key role. The deformation of the flexspline under load is not purely torsional; it involves a complex combination of bending, shearing, and membrane strains. The finite element model captures this coupled deformation field. The load-dependent torsional stiffness \(K_T(\theta)\) of the strain wave gear can be inferred from the overall twist angle \(\phi\) of the flexspline relative to the circular spline under torque \(T\): \(K_T = T / \phi\). The simulation shows that \(K_T\) increases with \(T\) initially as more teeth engage, then tends to stabilize at higher loads, reflecting the nonlinear engagement characteristic.

In summary, the comprehensive finite element simulation of the strain wave gear with a tri-arc spatial tooth profile provides deep insights into its load meshing performance. The key conclusions are as follows: First, the strategic placement of the minimum initial backlash near the wave generator’s major axis, combined with a convex-concave tooth pairing in that region, creates a low-pressure, high-area contact zone capable of carrying significant load efficiently. Second, the axial modification, which generates a controlled increase in initial backlash from the middle to the rear tooth section, successfully promotes the formation of a wider axial contact area under load, optimizing the use of the available tooth face width. Third, the load distribution among teeth is highly nonlinear. With increasing torque, the engagement zone expands, but the peak meshing force migrates towards the mesh-in side, where a group of teeth eventually form a plateau carrying substantial load. Fourth, the maximum contact pressure distribution around the circumference develops three peaks under high load. The absolute maximum pressure at the extreme load occurs on the mesh-in side due to a less favorable convex-convex contact, but the pressure in the major axis region remains relatively well-controlled due to the profile geometry. Finally, the maximum contact pressure consistently locates at the middle section of the tooth face, where radial support from the wave generator is strongest, thereby enhancing the effective load capacity and stiffness of the transmission.

This analysis underscores the value of advanced, non-linear FEA in the design and validation of high-performance strain wave gears. The methodology allows for the virtual testing of different profile geometries, modification schemes, and load scenarios before physical prototyping. Future work could involve coupling these mechanical simulations with thermal analysis to predict efficiency and heat generation, or with fatigue models to estimate service life. The insights gained specifically validate the tri-arc spatial profile as a promising design direction for strain wave gears demanding high torque capacity, stiffness, and reliability in precision applications such as robotic joints and aerospace actuators. The continuous evolution of strain wave gear technology relies on such detailed understanding of the intricate interplay between geometry, contact, and load.

To further quantify the relationships, let’s consider some derived parameters. The total engaged arc length \(\Theta_{eng}\) (in degrees) as a function of torque \(T\) can be fitted to a saturation curve:

$$ \Theta_{eng}(T) = \Theta_{max} \left(1 – e^{-k T}\right) + \Theta_0 $$

where \(\Theta_{max}\) is the maximum possible engagement arc, \(k\) is a constant, and \(\Theta_0\) is the arc at negligible load. From the simulation data, one can approximate these values. Similarly, the overall gear torsional stiffness \(K_{gear}\) can be expressed as a function of the meshing stiffness per tooth pair \(k_{mesh}\) and the number of engaged teeth. However, due to the non-uniform load sharing, the effective stiffness is:

$$ K_{gear} \approx r_{0f}^2 \sum_{i=1}^{N_{eng}} k_{mesh,i} \cdot \cos^2(\beta_i) $$

where \(k_{mesh,i}\) is the nonlinear mesh stiffness of the \(i\)-th pair, which depends on the contact area and penetration depth. The FEA simulation inherently accounts for this complexity by solving the complete contact mechanics problem. The superiority of the tri-arc profile in this strain wave gear context is evident from the extended uniform contact areas and the managed contact pressure levels across a broad load range, contributing to a more robust and predictable transmission behavior under demanding operational conditions.