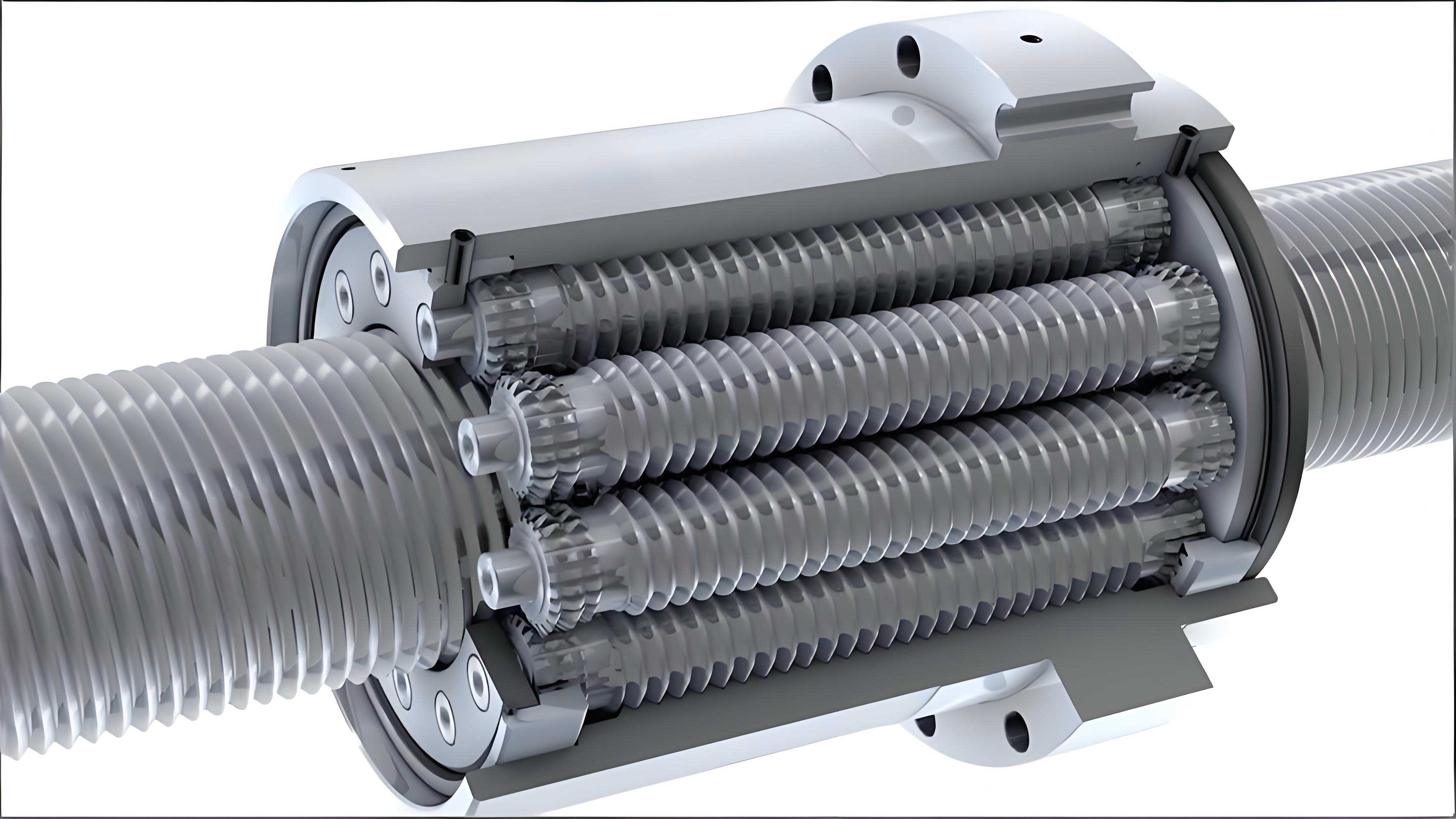

As a precision mechanical transmission component capable of converting rotary motion into linear motion, the planetary roller screw assembly (PRSM) represents a significant advancement over traditional ball screw mechanisms. Its superior load-carrying capacity, high stiffness, longevity, and resistance to shock have led to its increasing adoption in demanding fields such as aerospace, advanced vehicle systems, and high-precision machine tools. The core of its performance lies in the intricate contact interactions between the screw threads, the planetary rollers, and the nut threads. Therefore, a precise understanding of the contact characteristics, governed by the surface curvatures at the points of interaction, is paramount for predicting performance metrics like load distribution, efficiency, fatigue life, and thermal behavior. This paper aims to establish a generalized and rigorous analytical framework for calculating the principal curvatures at the contact interfaces within a planetary roller screw assembly and to subsequently analyze their influence on the Hertzian contact parameters.

The fundamental challenge in analyzing the contact mechanics of a planetary roller screw assembly stems from the complex geometry of the interacting surfaces. The screw, rollers, and nut feature helical raceways or thread flanks, which are spatial spiral surfaces. Traditional simplified approaches, often borrowed from ball screw analysis, model the roller thread as an equivalent sphere. However, this simplification introduces significant inaccuracies because the principal curvatures of the screw and nut raceways are not zero in one of the principal planes—they are not straight lines but curves defined by the lead angle. Furthermore, existing methods that derive curvature from thread parameter equations often involve cumbersome coordinate transformations. To address these shortcomings, this work develops a unified mathematical model based on the explicit geometry of the components in their normal cross-section, leading to a more direct and accurate calculation of the essential curvature parameters required for Hertzian contact theory.

The analysis begins by defining the geometry. For each component in the planetary roller screw assembly (screw, roller, nut), a Cartesian coordinate system $$o_i x_i y_i z_i$$ (where $$i = S, R, N$$) is established with its origin on the component’s central axis. The key innovation is describing the thread profile in the normal cross-section—the plane perpendicular to the helix tangent. This aligns with practical manufacturing processes. A local normal coordinate system $$o’_i x’_i y’_i z’_i$$ is obtained by rotating the original system about the $$x_i$$-axis by the lead angle $$\lambda_i$$. The thread profile contour lies within the $$o’_i x’_i z’_i$$ plane, with its origin on the component axis, simplifying subsequent derivations immensely compared to models where the origin is placed at the thread tooth center.

The contour of the screw raceway consists of two straight flanks (upper and lower contact surfaces). For a point on the lower flank, its coordinate $$z’_S$$ is given by the contour function $$\eta_S(r_{PS})$$. Considering the thread geometry with normal flank angle $$\beta_n$$ and pitch $$p_S$$, the helical surface equation for the screw in its own coordinate system is derived as:

$$

f_S(r_{PS}, \theta_{PS}) = \left[\xi \tan\beta_n \left( r_{PS} – r_S \right) + \frac{p_S \cos\lambda_S}{4} \right] \cos\lambda_S + \frac{l_S \theta_{PS}}{2\pi}

$$

where $$\xi = +1$$ denotes the lower contact surface and $$\xi = -1$$ the upper surface, $$r_{PS}$$ and $$\theta_{PS}$$ are the parametric coordinates, $$r_S$$ is the screw’s nominal (pitch) radius, and $$l_S = n_S p_S$$ is the lead ($$n_S$$ is the number of starts).

The roller in a planetary roller screw assembly has a circular arc profile with radius $$r_{Re}$$ in its normal section. Following a similar procedure for a point on its lower contact surface, the helical surface equation is:

$$

f_R(r_{PR}, \theta_{PR}) = \left[ \xi \left( r_{Re} \cos\beta_n + \frac{p_R \cos\lambda_R}{4} – \sqrt{r_{Re}^2 – (r_{PR} – r_R)^2} \right) \right] \cos\lambda_R + \frac{l_R \theta_{PR}}{2\pi}

$$

Here, $$r_R$$ is the roller’s nominal radius and $$l_R = p_R$$ (single-start).

The nut, being an internal thread, has a contour similar to the screw’s but with an opposite sense. Its helical surface equation is:

$$

f_N(r_{PN}, \theta_{PN}) = \left[-\xi \tan\beta_n \left( r_{PN} – r_N \right) + \frac{p_N \cos\lambda_N}{4} \right] \cos\lambda_N + \frac{l_N \theta_{PN}}{2\pi}

$$

where $$r_N$$ is the nut’s nominal radius. These unified equations, of the general form $$z_i = f_i(r_{Pi}, \theta_{Pi}) = \eta_i(r_{Pi}) \cos\lambda_i + l_i \theta_{Pi} / 2\pi$$, are the foundation for curvature analysis.

The principal curvatures at any point on a surface determine the shape and size of the contact patch under load. They are derived using differential geometry. First, the surface vector $$\mathbf{F}_i$$, its first derivatives ($$\mathbf{F}_{i,r}$$, $$\mathbf{F}_{i,\theta}$$), and second derivatives ($$\mathbf{F}_{i,rr}$$, $$\mathbf{F}_{i,r\theta}$$, $$\mathbf{F}_{i,\theta\theta}$$) are obtained from the parametric equation. The unit normal vector $$\mathbf{n}_i$$ at a point is calculated from the gradient of the implicit surface function $$F_i(r, \theta, z)=f_i(r, \theta)-z=0$$.

$$

\mathbf{n}_i(r_{Pi}, \theta_{Pi}) = \frac{ \text{grad} F_i }{ |\text{grad} F_i| }

$$

The first fundamental form coefficients (E, F, G) and the second fundamental form coefficients (L, M, N) are then computed:

$$

\begin{aligned}

E_i &= \mathbf{F}_{i,r} \cdot \mathbf{F}_{i,r}, \quad F_i = \mathbf{F}_{i,r} \cdot \mathbf{F}_{i,\theta}, \quad G_i = \mathbf{F}_{i,\theta} \cdot \mathbf{F}_{i,\theta} \\

L_i &= \mathbf{F}_{i,rr} \cdot \mathbf{n}_i, \quad M_i = \mathbf{F}_{i,r\theta} \cdot \mathbf{n}_i, \quad N_i = \mathbf{F}_{i,\theta\theta} \cdot \mathbf{n}_i

\end{aligned}

$$

The Gaussian curvature $$K_i$$ and the mean curvature $$H_i$$ follow:

$$

K_i = \frac{L_i N_i – M_i^2}{E_i G_i – F_i^2}, \quad H_i = \frac{G_i L_i – 2 F_i M_i + E_i N_i}{2(E_i G_i – F_i^2)}

$$

Finally, the principal curvatures $$\rho_{i,\text{max}}$$ and $$\rho_{i,\text{min}}$$ are:

$$

\rho_{i,\text{max}} = H_i + \sqrt{H_i^2 – K_i}, \quad \rho_{i,\text{min}} = H_i – \sqrt{H_i^2 – K_i}

$$

A positive curvature indicates a convex surface, while negative indicates concave.

For the contact mechanics analysis of the planetary roller screw assembly, we consider two interfaces: the screw-roller interface and the nut-roller interface. At each contact point, there are four principal curvatures: two for Body I (e.g., screw) and two for Body II (e.g., roller). According to Hertzian theory for elastic contact of two smooth surfaces, the contact area is generally an ellipse. The key parameters are the sum and the difference of the principal curvatures:

$$

\Sigma\rho = \rho_{\text{min}}^{I} + \rho_{\text{max}}^{I} + \rho_{\text{min}}^{II} + \rho_{\text{max}}^{II}

$$

$$

F(\rho) = \frac{ \left| \rho_{\text{max}}^{I} – \rho_{\text{min}}^{I} \right| + \left| \rho_{\text{max}}^{II} – \rho_{\text{min}}^{II} \right| }{\Sigma\rho}

$$

The function $$F(\rho)$$, related to the ellipticity parameter, determines the shape of the contact ellipse. For a given normal load $$Q$$ per thread contact and the equivalent elastic modulus $$E’$$ ($$1/E’ = (1-\nu_1^2)/E_1 + (1-\nu_2^2)/E_2$$), the semi-axes $$a$$ (major) and $$b$$ (minor) of the contact ellipse and the maximum contact stress $$\sigma_{\text{max}}$$ are:

$$

a = a^* \left( \frac{3Q}{2E’ \Sigma\rho} \right)^{1/3}, \quad b = b^* \left( \frac{3Q}{2E’ \Sigma\rho} \right)^{1/3}, \quad \sigma_{\text{max}} = \frac{3Q}{2\pi a b}

$$

The dimensionless coefficients $$a^*$$ and $$b^*$$ depend solely on $$F(\rho)$$ and are found from standard Hertzian solutions or tabulated values.

To validate the presented model and demonstrate its advantages, a numerical example is analyzed. The basic parameters of a standard planetary roller screw assembly are listed in the table below.

| Component | Nominal Radius (mm) | Lead (mm) | Number of Starts | Lead Angle (°) | Pitch (mm) | Normal Flank Angle (°) | Roller Profile Radius (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screw (S) | 15.0 | 10.0 | 5 | 6.0566 | 2.0 | 45 | — |

| Roller (R) | 5.0 | 2.0 | 1 | 3.6426 | 2.0 | 45 | 7.0700 |

| Nut (N) | 25.0 | 10.0 | 5 | 3.6426 | 2.0 | 45 | — |

Using the derived equations, the principal curvatures at the approximate contact points (using nominal radii) are calculated. The results are compared with those from the traditional equivalent ball model, as shown in the following table. The equivalent ball model assumes the roller profile curvature is the only non-zero principal curvature for the roller and that the screw/nut raceway has one zero curvature, which is a significant simplification.

| Contact Interface & Component | Principal Curvature 1 (mm⁻¹) | Principal Curvature 2 (mm⁻¹) | Equivalent Ball Model Result (Error) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screw-Roller Side: Screw | 0.0476 | -2.564×10⁻⁴ | 0.0469, 0 (Substantial error for 2nd curvature) |

| Screw-Roller Side: Roller | 0.1289 | 0.1543 | 0.1414, 0.1414 (Error ~9.9% and 8.3%) |

| Nut-Roller Side: Roller | 0.1289 | 0.1543 | 0.1414, 0.1414 (Error ~9.9% and 8.3%) |

| Nut-Roller Side: Nut | -0.0284 | 5.663×10⁻⁵ | -0.0282, 0 (Noticeable error for 2nd curvature) |

The comparison clearly shows that the equivalent ball model, while simpler, introduces considerable inaccuracies, particularly in calculating the second principal curvature for the screw and nut, which it incorrectly assumes to be zero. The curvature in the direction along the helix is indeed very small but non-zero due to the lead angle. The error for the roller’s principal curvatures is also significant (around 8-10%). This confirms the necessity of the more rigorous model developed in this work for accurate contact analysis in a planetary roller screw assembly.

Next, the influence of key design parameters of the planetary roller screw assembly on the contact characteristics is investigated. Assuming a normal load of Q = 200 N per engaged thread, we analyze the effects of varying the pitch $$p$$ and the normal flank angle $$\beta_n$$. The computed parameters are the curvature difference $$F(\rho)$$, the contact ellipse area $$A_{ell} = \pi a b$$, and the maximum contact stress $$\sigma_{max}$$ for both the screw-roller (S-R) and nut-roller (N-R) interfaces.

Effect of Pitch/Lead Angle: Increasing the pitch (and consequently the lead angle, for a fixed nominal radius) directly affects the geometry of the helical surfaces. The analysis yields the following trends:

– The curvature difference $$F(\rho)$$ increases for both contact interfaces as the pitch grows. This indicates that the contact ellipse becomes more eccentric (elongated).

– Interestingly, the contact ellipse area remains almost constant despite the change in pitch.

– The maximum contact stress is also largely insensitive to changes in pitch within the practical range.

– A consistent finding is that the contact area on the nut-roller side is larger than that on the screw-roller side, leading to a lower maximum contact stress on the N-R interface. This asymmetry is an inherent characteristic of the planetary roller screw assembly geometry.

The underlying reason is that while $$\Sigma\rho$$ changes with pitch, the functional relationship in the Hertz equations compensates in a way that keeps the product $$a b$$ relatively stable for a given load. However, the change in $$F(\rho)$$ signifies a change in the ellipse’s shape, which could influence lubrication and wear patterns.

Effect of Normal Flank Angle: The normal flank angle $$\beta_n$$ is a critical parameter defining the thread profile. Its variation shows a distinct influence:

– Increasing $$\beta_n$$ causes the curvature difference $$F(\rho)$$ to decrease for both interfaces. This means the contact ellipse becomes more circular.

– Simultaneously, the contact ellipse area decreases with a larger flank angle.

– Consequently, the maximum contact stress $$\sigma_{max}$$ increases significantly with $$\beta_n$$, as the same load is distributed over a smaller area.

This analysis provides crucial design insight for the planetary roller screw assembly. While a larger flank angle reduces sliding (by making the contact more circular) and might simplify manufacturing, it leads to higher contact stresses. Excessive contact stress accelerates fatigue and increases friction, potentially reducing efficiency and service life. Therefore, optimizing the normal flank angle involves a trade-off between reducing sliding friction and minimizing contact stress to ensure durability.

In conclusion, this work presents a comprehensive and generalized analytical framework for the precise calculation of principal curvatures at the contact interfaces within a planetary roller screw assembly. By deriving unified helical surface equations based on normal cross-section profiles, the method eliminates the need for tedious coordinate transformations inherent in some previous models and provides a more accurate foundation than the simplified equivalent ball approach. The results conclusively demonstrate that the principal curvatures of the screw and nut raceways are not zero in any principal plane, and using nominal radii for initial curvature estimation is acceptably accurate. Applying Hertzian contact theory with these accurately calculated curvatures allows for a detailed analysis of how key design parameters—specifically the pitch and the normal flank angle—affect the contact ellipse geometry and stress state. The findings offer valuable guidance for the design and optimization of planetary roller screw assemblies, emphasizing the need to balance geometric parameters to achieve desired performance characteristics such as load capacity, efficiency, and longevity. Future work may integrate these local contact models into a system-level analysis to predict overall load distribution, stiffness, and thermal behavior of the complete planetary roller screw assembly.