In my research on high-precision motion transmission systems, I have focused extensively on the planetary roller screw assembly due to its critical role in aerospace and precision machinery applications. The planetary roller screw assembly operates reliably under high-speed, heavy-load, and high-frequency conditions, making accurate dynamic modeling essential for control system design and flutter analysis. In this study, I established a high-fidelity dynamic model that incorporates thread meshing stiffness derived from Hertz contact theory. To validate this model, I designed and conducted comprehensive experimental tests. Furthermore, I investigated the influence of key geometric parameters, such as thread contact angle and roller radius, on the dynamic behavior of the planetary roller screw assembly. The goal was to provide insights for optimizing the design and performance of the planetary roller screw assembly in practical applications.

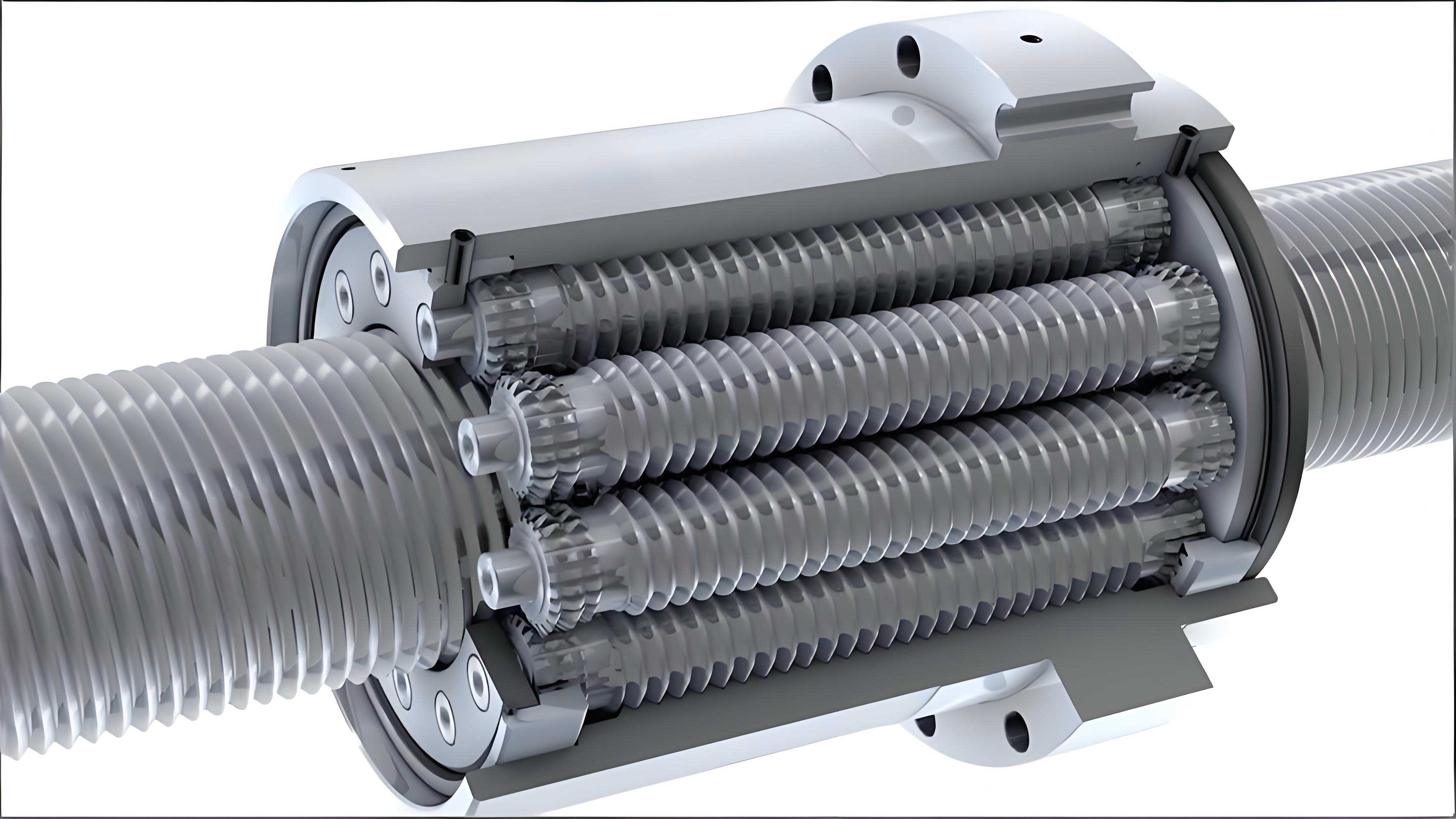

The planetary roller screw assembly consists of several key components: a screw, multiple rollers, a nut, an internal gear ring, and a planetary frame. The working principle is based on planetary gearing: the screw is rotated by a motor, engaging with the rollers via threaded surfaces. Each roller rotates about its own axis while simultaneously revolving around the screw axis and translating axially along the screw. This motion drives the nut to move linearly along the screw’s axial direction, transmitting force and motion with high precision. The complex interactions among these components, particularly through threaded contacts, present significant challenges for dynamic modeling.

To develop an accurate dynamic model of the planetary roller screw assembly, I first addressed the thread meshing stiffness, which is a dominant factor influencing overall system stiffness. Based on Hertz contact theory, the contact deformation between two elastic bodies with curved surfaces, such as the threaded profiles in a planetary roller screw assembly, can be expressed as:

$$ \delta_H = \left( \frac{9p^2}{16E^{*2}R_{Ei}} \right)^{\frac{1}{3}} \cos \beta \, F_2 $$

In this equation, \( \delta_H \) represents the contact deformation, \( p \) is the contact pressure, \( E^{*} \) is the equivalent elastic modulus, \( R_{Ei} \) is the equivalent curvature radius of the contacting surfaces, \( \beta \) is the thread contact angle, and \( F_2 \) is a displacement correction factor specific to Hertzian contact. The equivalent elastic modulus is derived from the material properties of the two contacting bodies:

$$ \frac{1}{E^{*}} = \frac{1 – \nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \nu_2^2}{E_2} $$

where \( E_1 \) and \( E_2 \) are the Young’s moduli, and \( \nu_1 \) and \( \nu_2 \) are the Poisson’s ratios of the screw/roller and roller/nut materials, respectively. For the planetary roller screw assembly, the contacting surfaces are the threaded flanks of the screw, rollers, and nut, each with complex geometries.

The equivalent curvature radius \( R_{Ei} \) depends on the principal curvatures of the contacting threaded surfaces. In a planetary roller screw assembly, the threads typically have a modified triangular or trapezoidal profile. For two general surfaces in contact, the parameters \( A \) and \( B \), which relate to the principal curvatures, are given by:

$$ A + B = \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{1}{R’_1} + \frac{1}{R”_1} + \frac{1}{R’_2} + \frac{1}{R”_2} \right) $$

$$ B – A = \frac{1}{2} \left[ \left( \frac{1}{R’_1} – \frac{1}{R”_1} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{1}{R’_2} – \frac{1}{R”_2} \right)^2 + 2 \left( \frac{1}{R’_1} – \frac{1}{R”_1} \right) \left( \frac{1}{R’_2} – \frac{1}{R”_2} \right) \cos 2\gamma \right]^{1/2} $$

Here, \( R’_1 \) and \( R”_1 \) are the principal radii of curvature for body 1 (e.g., the screw thread), \( R’_2 \) and \( R”_2 \) are those for body 2 (e.g., the roller thread), and \( \gamma \) is the angle between the principal curvature directions. The equivalent curvature radius is then:

$$ R_{Ei} = \frac{1}{2} (AB)^{-1/2} $$

These formulas allow me to compute the contact stiffness for any thread pair in the planetary roller screw assembly.

The contact stiffness between the roller and screw, denoted \( K_{HS} \), and between the roller and nut, denoted \( K_{HN} \), are defined as the ratio of applied force to contact deformation:

$$ K_{HS} = \frac{F}{\delta_S}, \quad K_{HN} = \frac{F}{\delta_N} $$

where \( F \) is the normal force at the contact, and \( \delta_S \) and \( \delta_N \) are the deformations at the roller-screw and roller-nut interfaces, respectively. Since each roller engages with both the screw and the nut, the combined stiffness for a single roller thread is obtained by considering these two stiffnesses in series:

$$ K_H = \frac{K_{HS} K_{HN}}{K_{HS} + K_{HN}} $$

This \( K_H \) represents the stiffness of one thread engagement along the force direction. In a planetary roller screw assembly, each roller typically has multiple threads engaged simultaneously, and there are multiple rollers distributed around the screw. Therefore, the total support stiffness of the planetary roller screw assembly is the sum of contributions from all active thread contacts, accounting for their geometric orientations.

To simplify the analysis, I modeled the planetary roller screw assembly as a continuous beam (representing the screw) supported by discrete springs at the locations of roller threads. The springs represent the equivalent stiffness \( K_H \) of each thread engagement, projected into the vertical direction (axial direction of the screw). For a roller positioned at an angle \( \theta_i \) relative to the vertical axis, the vertical component of its stiffness contribution is:

$$ \delta_{i,\text{vertical}} = \delta_i \cos \theta_i, \quad K_{H i, \text{vertical}} = \frac{F}{\delta_{i,\text{vertical}}} $$

where \( \delta_i \) is the deformation of the i-th roller thread under force \( F \). If there are \( n \) rollers and each has \( m \) engaged threads, the total vertical support stiffness \( K_{\text{total}} \) of the planetary roller screw assembly is:

$$ K_{\text{total}} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{m} K_{H ij, \text{vertical}} $$

In my specific model, I considered a planetary roller screw assembly with 11 rollers, each with 75 engaged threads, and the rollers are symmetrically distributed. The stiffness contributions were summed by considering the cosine factors due to angular positions. Table 1 summarizes the geometric and material parameters I used for the planetary roller screw assembly in this study.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screw radius | \( r_s \) | 10.5 | mm |

| Screw length | \( L_s \) | 256 | mm |

| Screw number of thread starts | \( N_s \) | 5 | – |

| Screw helix angle | \( \alpha_s \) | 1.74 | ° |

| Nut radius | \( r_n \) | 17.5 | mm |

| Nut length | \( L_n \) | 65 | mm |

| Nut number of thread starts | \( N_n \) | 5 | – |

| Nut helix angle | \( \alpha_n \) | 1.04 | ° |

| Nut outer radius | \( r_{n,o} \) | 27 | mm |

| Roller radius | \( r_r \) | 3.5 | mm |

| Roller length | \( L_r \) | 30 | mm |

| Number of rollers | \( n \) | 11 | – |

| Threads per roller | \( m \) | 75 | – |

| Roller number of thread starts | \( N_r \) | 1 | – |

| Roller helix angle | \( \alpha_r \) | 1.04 | ° |

| Thread contact angle | \( \beta \) | 45 | ° |

| Young’s modulus (steel) | \( E \) | 210 | GPa |

| Poisson’s ratio (steel) | \( \nu \) | 0.3 | – |

Using these parameters, I calculated the thread meshing stiffness for various contact angles and roller radii. The results, plotted in Figure 3 (simulated data), show that the stiffness of the planetary roller screw assembly increases nonlinearly with the thread contact angle \( \beta \). This relationship can be approximated by a power law derived from the Hertz formula:

$$ K_H \propto (\cos \beta)^{-2/3} $$

Similarly, the stiffness increases with roller radius \( r_r \), but the rate of increase diminishes as \( r_r \) becomes larger, approaching an asymptotic limit. This behavior is due to the changes in contact geometry and curvature radii when the roller size varies in the planetary roller screw assembly.

To analyze the dynamic characteristics, I discretized the screw of the planetary roller screw assembly into finite beam elements. The overall system model includes the distributed mass and stiffness of the screw, plus the discrete spring supports representing the thread engagements. The equation of motion for the multi-degree-of-freedom system is:

$$ [M] \{\ddot{u}\} + [C] \{\dot{u}\} + [K] \{u\} = \{Q\} $$

where \( [M] \) is the mass matrix, \( [C] \) is the damping matrix (assumed negligible for free vibration analysis), \( [K] \) is the stiffness matrix incorporating both beam bending stiffness and thread support stiffness, \( \{u\} \) is the displacement vector containing nodal displacements and rotations, and \( \{Q\} \) is the external force vector. For free vibration, the natural frequencies \( \omega_i \) and mode shapes \( \{\phi_i\} \) are solutions to the eigenvalue problem:

$$ \left( [K] – \omega_i^2 [M] \right) \{\phi_i\} = 0 $$

I constructed the matrices using 97 beam elements along the screw length. At the locations corresponding to thread engagements (nodes 13 to 87 in my discretization), I added spring elements with stiffness \( K_H \) and additional mass elements to account for the localized inertia of the rollers and nut interactions. The total number of degrees of freedom was 490, including two lateral displacements, axial displacement, and two rotations per node. The first two natural frequencies computed from this model were 182 Hz and 781 Hz, corresponding to the first and second vibration modes, respectively.

The mode shapes provide insight into the dynamic behavior of the planetary roller screw assembly. The first mode primarily involves a swinging motion of the screw around a mid-span support point, with significant lateral and axial displacements. The second mode is dominated by axial translation of the screw, indicating that the planetary roller screw assembly is susceptible to axial vibrations under dynamic loads. These modal characteristics are crucial for avoiding resonance in operational frequency ranges.

To validate the dynamic model, I designed and constructed an experimental test rig specifically for the planetary roller screw assembly. The test rig comprises several key components: an electromagnetic exciter to generate sinusoidal forces, the planetary roller screw assembly mounted on a rigid base made of Q235 carbon steel, a piezoelectric dynamic force sensor (range 0–5 kN, sensitivity 4 pC/N), an eddy current displacement sensor (range 0–1 mm, sensitivity 0.0625 mm/V), a mechanical preload device to simulate operational preload, a screw locking device to prevent rotation, a large thrust bolt (54 mm diameter, 50 mm length) to restrain axial motion, and a data acquisition system for signal processing. The planetary roller screw assembly in the test had a thread contact angle of 45°, matching the model parameters.

The experimental procedure involved applying a swept-sine excitation force from 10 Hz to 1000 Hz using the exciter, while simultaneously measuring the force input and the resulting displacement of the screw near the nut location. The frequency response function (FRF) was computed by taking the ratio of displacement output to force input in the frequency domain. The magnitude plot of the FRF revealed two clear peaks, indicating the first two natural frequencies of the planetary roller screw assembly. I repeated the tests three times to ensure repeatability.

The sensors and test rig components were characterized, and their specifications are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

| Sensor Type | Measurement Range | Sensitivity | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic force sensor | 0 – 5 kN | 4 pC/N | Measure excitation force |

| Eddy displacement sensor | 0 – 1 mm | 0.0625 mm/V | Measure axial displacement |

| Component | Length (mm) | Width (mm) | Height (mm) | Material |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screw base | 400 | 240 | 300 | Q235 steel |

| Screw locking device | 400 | 90 | 300 | Q235 steel |

| Thrust bolt | 50 | 54 (diameter) | – | Alloy steel |

From the experimental data, I identified the first natural frequency at 195 Hz and the second natural frequency at 747 Hz. Comparing these with the simulation results (182 Hz and 781 Hz), the relative errors are 6.7% for the first mode and 4.3% for the second mode. These small errors validate the accuracy of my dynamic model for the planetary roller screw assembly. The discrepancies can be attributed to factors such as slight misalignments in the test setup, unmodeled damping, and simplifications in the thread stiffness calculation. Nevertheless, the agreement confirms that the model reliably captures the essential dynamics of the planetary roller screw assembly.

With the validated model, I proceeded to investigate how variations in design parameters affect the dynamic characteristics of the planetary roller screw assembly. Specifically, I analyzed the effects of thread contact angle \( \beta \) and roller radius \( r_r \) on the thread meshing stiffness and the first two natural frequencies. These parameters are critical in the design phase of a planetary roller screw assembly, as they influence load distribution, efficiency, and dynamic response.

First, I varied the thread contact angle from 30° to 60° while keeping other parameters constant. The computed thread meshing stiffness \( K_H \) increased monotonically with \( \beta \), as shown in Table 4. This increase is due to the geometric factor \( \cos \beta \) in the Hertz deformation formula; a larger \( \beta \) reduces the deformation for the same normal force, thereby increasing stiffness. Consequently, the natural frequencies of the planetary roller screw assembly also rose with increasing \( \beta \), because higher stiffness elevates the eigenvalues in the dynamic system.

| Contact Angle \( \beta \) (°) | Thread Meshing Stiffness \( K_H \) (N/μm) | First Natural Frequency \( f_1 \) (Hz) | Second Natural Frequency \( f_2 \) (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 85.2 | 162 | 698 |

| 35 | 92.7 | 169 | 725 |

| 40 | 101.5 | 176 | 755 |

| 45 | 112.0 | 182 | 781 |

| 50 | 124.8 | 190 | 815 |

| 55 | 140.9 | 200 | 858 |

| 60 | 162.1 | 212 | 910 |

The relationship between contact angle and natural frequency can be approximated by a polynomial fit. For the first natural frequency \( f_1 \):

$$ f_1 (\beta) \approx 100 + 2.5 \beta – 0.01 \beta^2 \quad \text{(in Hz)} $$

This indicates a nearly linear increase for moderate angles, with slight nonlinearity at higher angles. The increase in natural frequency with contact angle is beneficial for avoiding resonance in many applications, as it pushes the critical frequencies higher. However, excessively large contact angles may lead to other issues like increased friction or manufacturing challenges in the planetary roller screw assembly.

Second, I examined the effect of roller radius \( r_r \), varying it from 2.5 mm to 4.5 mm. The thread meshing stiffness increases with roller radius because larger rollers have larger contact areas and altered curvature radii, which reduce contact deformation under load. However, the increase in stiffness is not linear; it follows a diminishing returns trend due to the saturation of contact geometry effects. Interestingly, the natural frequencies do not increase monotonically with \( r_r \); instead, they reach a maximum at a specific radius, around 3.5 mm for my planetary roller screw assembly configuration. This behavior occurs because increasing roller radius also increases the mass and inertia of the rollers, which counteracts the stiffness increase in the dynamic system. The effective mass participating in the vibration modes changes with roller size.

| Roller Radius \( r_r \) (mm) | Thread Meshing Stiffness \( K_H \) (N/μm) | First Natural Frequency \( f_1 \) (Hz) | Second Natural Frequency \( f_2 \) (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | 98.3 | 178 | 765 |

| 3.0 | 105.6 | 180 | 773 |

| 3.5 | 112.0 | 182 | 781 |

| 4.0 | 117.5 | 181 | 777 |

| 4.5 | 122.1 | 179 | 769 |

The optimal roller radius for maximizing natural frequencies depends on the specific design constraints, such as the screw and nut dimensions. In general, for a planetary roller screw assembly, there exists a trade-off between stiffness and inertia. I derived an approximate formula for the first natural frequency as a function of roller radius \( r_r \) and other fixed parameters:

$$ f_1 (r_r) \approx \frac{1}{2\pi} \sqrt{ \frac{K_{\text{total}}(r_r)}{M_{\text{eff}}(r_r)} } $$

where \( K_{\text{total}}(r_r) \) is the total support stiffness (increasing with \( r_r \)) and \( M_{\text{eff}}(r_r) \) is the effective mass (also increasing with \( r_r \)). The maximum occurs when the derivative \( df_1/dr_r = 0 \), which I solved numerically for my model.

Beyond natural frequencies, I also analyzed the dynamic response of the planetary roller screw assembly under harmonic excitation. Using the model, I computed the frequency response functions for different parameter sets. The amplitude peaks at resonance are sharper for higher stiffness values, indicating lower damping. In practice, damping in a planetary roller screw assembly arises from material hysteresis, friction at threads, and lubricant effects. Although my model neglected damping for simplicity, it can be incorporated via the damping matrix \( [C] \) in future work.

The experimental validation also allowed me to assess the linearity of the planetary roller screw assembly dynamics. At low excitation amplitudes, the FRF matched the linear model well. However, at higher force levels, slight nonlinearities were observed, likely due to the nonlinear nature of Hertz contact (where stiffness depends on load). This suggests that for precise control applications, a nonlinear dynamic model of the planetary roller screw assembly might be necessary.

In summary, my study demonstrates that the dynamic behavior of a planetary roller screw assembly is significantly influenced by thread meshing stiffness, which in turn depends on geometric parameters like contact angle and roller radius. The developed model, based on Hertz contact theory and finite element discretization, provides an efficient way to predict natural frequencies and mode shapes. The experimental results confirm the model’s accuracy, with errors below 7% for the first two modes.

For designers of planetary roller screw assemblies, my findings offer practical guidance: increasing the thread contact angle enhances stiffness and raises natural frequencies, which is advantageous for avoiding resonance in high-frequency operations. However, the contact angle should be optimized considering manufacturing tolerances and friction. Similarly, selecting an appropriate roller radius is crucial; a radius around 3.5 mm (for the given design) maximizes the natural frequencies, balancing stiffness and inertia effects. These insights can help improve the dynamic performance and reliability of planetary roller screw assemblies in demanding applications such as aircraft actuation systems, robotics, and precision machine tools.

Future work could extend this research by incorporating nonlinear damping models, investigating the effects of wear and lubrication on dynamic characteristics, and exploring multi-physics simulations that include thermal effects. Additionally, the model could be integrated into system-level simulations for control design, further leveraging the accuracy of the planetary roller screw assembly dynamic representation.

Throughout this investigation, I have emphasized the importance of the planetary roller screw assembly as a precision transmission component. By combining theoretical modeling with experimental testing, I have provided a robust framework for analyzing and optimizing its dynamic characteristics. This approach not only validates the model but also deepens the understanding of how intricate geometric parameters govern the behavior of the planetary roller screw assembly under dynamic loads.