In this article, I will delve into the intricate workings of a specialized transmission mechanism known as the planetary roller screw assembly, with a particular focus on its bearing-type variant. The planetary roller screw assembly is a high-precision mechanical device that converts rotary motion into linear motion, or vice versa, through the meshing of threads and gears. Compared to traditional ball screw assemblies, the planetary roller screw assembly offers superior load capacity, longer service life, higher transmission accuracy, and compact size, making it indispensable in advanced fields such as robotics, aerospace, and new energy equipment. Here, I aim to analyze the motion principles, derive theoretical formulas, and investigate the contact forces under various external loads for the bearing-type planetary roller screw assembly. I will employ multi-body dynamics simulation software to validate theoretical models and provide insights that can aid in optimizing the overall performance of the planetary roller screw assembly.

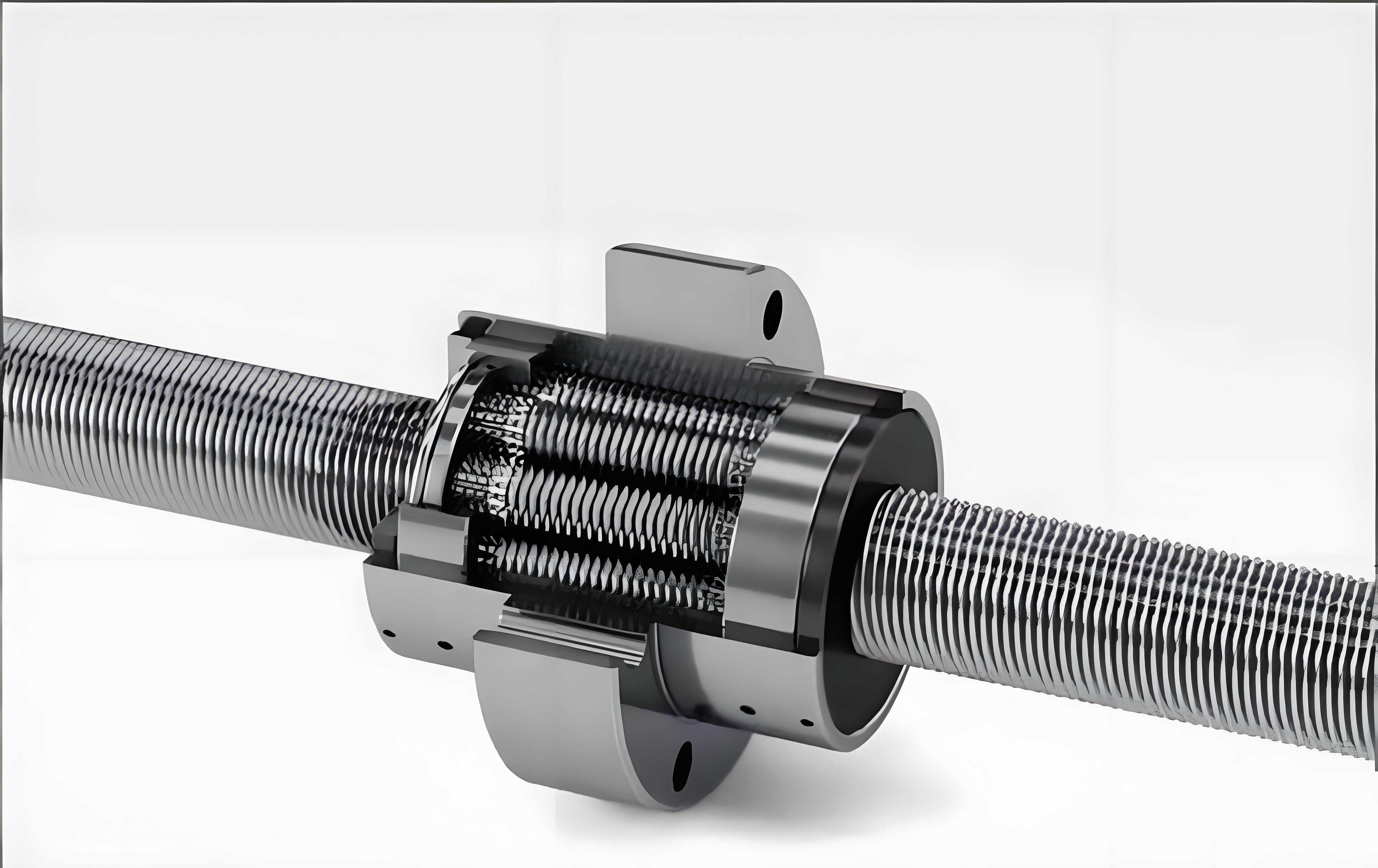

The bearing-type planetary roller screw assembly, a derivative of the standard planetary roller screw assembly, features a unique design where the screw engages with multiple rollers having ring-groove tooth profiles, and these rollers, in turn, engage with a nut that also has ring-groove teeth. This configuration enhances load distribution and reduces wear, further improving efficiency. I will begin by describing the structural composition of this planetary roller screw assembly, followed by a detailed derivation of its geometric motion relationships. Subsequently, I will establish a three-dimensional model and conduct dynamic simulations to obtain key motion parameters, comparing them with theoretical calculations. Finally, I will analyze the contact forces between critical components—such as the roller-screw, roller-nut, and threaded carrier-screw interfaces—under varying external loads, highlighting trends and implications for design optimization.

The core components of the bearing-type planetary roller screw assembly include the screw, rollers, nut assembly, and threaded carrier. The screw is a multi-start thread with a triangular tooth profile of 60°, while the rollers and the bearing ring (part of the nut assembly) feature ring-groove profiles without helix angles. Specifically, the rollers have spherical contour ring grooves that serve dual functions: transmitting motion and acting as an internal ring gear to maintain parallel alignment between the roller axes and the screw axis, preventing tilting. To boost load capacity and minimize friction, thrust cylindrical roller bearings are incorporated at both ends of the bearing ring, allowing it to rotate freely. The threaded carrier, along with retaining rings, ensures uniform circumferential distribution of the rollers. Unlike other planetary roller screw assembly types, the nut in this variant is not a single part but an assembly comprising the bearing ring, housing, thrust cylindrical roller bearings, and end covers. This design disperses frictional forces circumferentially, enhancing transmission efficiency. The force transmission path in this planetary roller screw assembly is as follows: the screw transfers force to the rollers via thread-ring groove meshing, then to the bearing ring, followed by the thrust cylindrical roller bearings, and finally to the end covers. This intricate arrangement underscores the robustness of the planetary roller screw assembly in heavy-duty applications.

To understand the motion characteristics of the planetary roller screw assembly, I will derive the theoretical formulas for its kinematic parameters. Consider the schematic representation of the bearing-type planetary roller screw assembly, where the screw rotates about its axis, the rollers undergo both rotation about their own axes (self-rotation) and revolution around the screw axis, and the nut assembly primarily translates axially. Assuming negligible circumferential motion of the bearing ring, I can analyze the absolute velocities at key points. Let \(d_s\), \(d_r\), and \(d_n\) denote the pitch diameters of the screw, roller, and nut, respectively, and \(d_c\) be the revolution diameter of the rollers. The angular velocities are defined as: \(\omega_s\) for the screw, \(\omega_r\) for the roller self-rotation, and \(\omega_c\) for the roller revolution (i.e., the angular velocity of the threaded carrier). Based on the instant center of rotation, the absolute velocity at point O can be expressed as:

$$ v_o = \frac{v_\alpha}{2} = \frac{\omega_s d_s}{4} $$

where \(v_\alpha\) is the linear velocity of the screw at point α. Alternatively, this velocity can be written in terms of the revolution motion:

$$ v_o = \frac{\omega_c d_c}{2} $$

Equating these expressions yields the relationship for the revolution angular velocity:

$$ \omega_c = \frac{d_s}{2d_c} \omega_s $$

The planetary roller screw assembly operates akin to a planetary gear train, allowing me to apply the gear ratio formula. The transmission ratio between the screw and roller, considering the carrier (threaded carrier), is given by:

$$ i_{H}^{sr} = \frac{\omega_s – \omega_c}{\omega_r – \omega_c} = -\frac{d_r}{d_s} $$

Solving for the roller self-rotation angular velocity \(\omega_r\), I obtain:

$$ \omega_r = \left[ \left( \frac{d_s}{d_r} + 1 \right) \omega_c – \frac{d_s}{d_r} \omega_s \right] $$

For the axial displacement, since the rollers have ring-groove profiles with zero pitch (\(p_r = 0\)), the relative axial displacement of the nut with respect to the screw can be derived. The axial displacement \(L\) of the roller relative to the screw over time \(t\) is:

$$ L = \left( \frac{\omega_r}{2\pi} p_r \pm \frac{\omega_c}{2\pi} n p_s \pm \frac{\omega_s}{2\pi} n p_s \right) t $$

where \(n\) is the number of screw starts, \(p_s\) is the screw pitch, and the ± signs indicate direction (positive for opposite rotations, negative for same rotations). Given \(p_r = 0\), this simplifies to the nut axial displacement \(L_n\):

$$ L_n = L = \left( \pm \frac{\omega_c}{2\pi} n p_s \pm \frac{\omega_s}{2\pi} n p_s \right) t $$

Differentiating with respect to time gives the axial velocity of the nut:

$$ v_n = \pm \frac{\omega_c}{2\pi} n p_s \pm \frac{\omega_s}{2\pi} n p_s $$

These formulas provide a foundational understanding of the motion in a planetary roller screw assembly. To further elucidate, I can summarize the key geometric parameters in a table, which aids in visualizing the design specifications.

| Component | Major Diameter (mm) | Pitch Diameter (mm) | Minor Diameter (mm) | Number of Starts | Tooth Angle (°) | Helix Angle (°) | Pitch/Spacing (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screw | 32.68 | 32.00 | 31.20 | 12 | 60 | 6.81 | 1.00 |

| Roller | 8.18 | 7.50 | 6.70 | — | 60 | — | 1.00 (ring groove spacing) |

| Nut | 47.80 | 47.00 | 46.32 | — | 60 | — | 1.00 (ring groove spacing) |

| Threaded Carrier | 32.80 | 32.00 | 31.32 | 12 | 60 | 6.81 | 1.00 |

This table encapsulates the critical dimensions of the planetary roller screw assembly components, facilitating subsequent analysis. Moving on, I will investigate the contact forces within the planetary roller screw assembly, as they directly impact durability and performance. When external loads are applied, contact forces arise at the meshing interfaces along the thread flanks. For the roller-screw contact, the normal contact force \(F_n\) can be decomposed into axial, radial, and tangential components: \(F_a\), \(F_r\), and \(F_t\), respectively. Similarly, for the roller-nut contact, the normal force \(F’_n\) decomposes into axial \(F’_a\) and radial \(F’_r\) components. Let \(\tau\) be the half-tooth angle and \(\lambda\) the helix angle of the screw. The relationships among these forces are:

$$ F_t = F_a \tan \lambda $$

$$ F_r = F_a \tan \tau $$

$$ F_n = F_a \sqrt{1 + \tan^2 \lambda + \tan^2 \tau} $$

For the roller-nut side:

$$ F’_r = F’_a \tan \tau $$

$$ F’_n = F’_a \sqrt{1 + \tan^2 \tau} $$

These equations are pivotal for evaluating load distribution in the planetary roller screw assembly. To validate the theoretical motion principles and analyze dynamic behavior, I developed a three-dimensional model of the bearing-type planetary roller screw assembly with 12 rollers, omitting some bearing rollers to reduce computational complexity. The model was imported into multi-body dynamics simulation software, where material properties were set to bearing steel, and appropriate joints and constraints were applied. For instance, fixed joints were used for non-moving parts, a revolute joint for the screw, cylindrical joints for carriers, and contacts were defined between interacting components using the Impact function for force calculation. The contact parameters included: stiffness coefficient \(K = 1 \times 10^5 \, \text{N/mm}\), stiffness exponent \(e = 1.5\), damping \(C = 50 \, \text{N·s/mm}\), and penetration depth \(d = 0.2 \, \text{mm}\). Friction was modeled using the Coulomb method with static friction coefficient \(\mu_s = 0.3\), dynamic friction coefficient \(\mu_d = 0.25\), static slip velocity \(v_s = 900 \, \text{mm/s}\), and dynamic slip velocity \(v_d = 1000 \, \text{mm/s}\). A rotational drive of \(157.08 \, \text{rad/s}\) was applied to the screw, and simulations were run for \(0.1 \, \text{s}\) with 100 steps. External loads were varied on the nut to study contact force responses.

The simulation results for motion parameters were compared with theoretical values. For the screw angular velocity \(\omega_s = 157.08 \, \text{rad/s}\), the theoretical revolution angular velocity from Equation (3) is \(\omega_c = 63.63 \, \text{rad/s}\). The simulated average revolution angular velocity was \(\omega’_c = 63.20 \, \text{rad/s}\), with fluctuations between \(52.98 \, \text{rad/s}\) and \(73.45 \, \text{rad/s}\). The theoretical roller self-rotation angular velocity from Equation (5) is \(\omega_r = -335.10 \, \text{rad/s}\), while the simulated average was \(\omega’_r = -327.97 \, \text{rad/s}\), ranging from \(-247.18 \, \text{rad/s}\) to \(-405.07 \, \text{rad/s}\). The nut axial velocity theoretical value from Equation (8) is \(v_n = -178.48 \, \text{mm/s}\), and the simulated average was \(v’_n = -178.83 \, \text{mm/s}\), with variations from \(-6.91 \, \text{mm/s}\) to \(-274.13 \, \text{mm/s}\). Over \(0.1 \, \text{s}\), the theoretical nut axial displacement is \(L_n = -17.85 \, \text{mm}\), and the simulated value was \(L’_n = -17.87 \, \text{mm}\). The relative errors between theoretical and simulated values ranged from \(0.14\%\) to \(2.13\%\), confirming the validity of the simulation approach for the planetary roller screw assembly. These comparisons are summarized in the table below, which highlights the close agreement and underscores the reliability of the derived formulas.

| Motion Parameter | Theoretical Value | Simulated Average Value | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revolution Angular Velocity (\(\omega_c\), rad/s) | 63.63 | 63.20 | 0.68% |

| Roller Self-Rotation Angular Velocity (\(\omega_r\), rad/s) | -335.10 | -327.97 | 2.13% |

| Nut Axial Velocity (\(v_n\), mm/s) | -178.48 | -178.83 | 0.20% |

| Nut Axial Displacement (\(L_n\), mm) | -17.85 | -17.87 | 0.11% |

Next, I analyzed the contact forces in the planetary roller screw assembly under different external loads applied to the nut: 40 kN, 70 kN, and 100 kN. The contact forces between roller-nut and roller-screw interfaces were extracted from simulations. For an external load \(F = 40 \, \text{kN}\), the roller-nut contact force fluctuated between \(2857.93 \, \text{N}\) and \(3597.57 \, \text{N}\), with an average of \(3333.90 \, \text{N}\). The roller-screw contact force ranged from \(3022.33 \, \text{N}\) to \(3611.35 \, \text{N}\), averaging \(3278.18 \, \text{N}\). At \(F = 70 \, \text{kN}\), the roller-nut contact force was between \(5362.77 \, \text{N}\) and \(6433.75 \, \text{N}\) (average \(5819.23 \, \text{N}\)), and the roller-screw contact force between \(5012.65 \, \text{N}\) and \(6083.01 \, \text{N}\) (average \(5533.97 \, \text{N}\)). For \(F = 100 \, \text{kN}\), the roller-nut contact force varied from \(7789.30 \, \text{N}\) to \(8942.79 \, \text{N}\) (average \(8330.07 \, \text{N}\)), and the roller-screw contact force from \(7452.67 \, \text{N}\) to \(8037.85 \, \text{N}\) (average \(7759.24 \, \text{N}\)). Clearly, both contact forces increase with external load, but the roller-nut contact force consistently exceeds the roller-screw contact force, with the gap widening as load rises. This is attributed to the threaded carrier分担部分 of the roller-screw contact force. To quantify, the contact forces for the threaded carrier-screw interfaces were also examined. For two threaded carriers (labeled 1 and 2), the average contact forces at \(F = 40 \, \text{kN}\) were \(257.12 \, \text{N}\) and \(399.96 \, \text{N}\); at \(F = 70 \, \text{kN}\), \(1627.89 \, \text{N}\) and \(1805.26 \, \text{N}\); and at \(F = 100 \, \text{kN}\), \(3405.57 \, \text{N}\) and \(3818.81 \, \text{N}\), respectively. These forces also escalate with external load, and carrier 2 experiences higher forces than carrier 1, likely due to asymmetric load distribution in the planetary roller screw assembly. The trends are encapsulated in the following table, which provides a comprehensive view of contact force behavior.

| External Load (kN) | Average Roller-Nut Contact Force (N) | Average Roller-Screw Contact Force (N) | Average Threaded Carrier 1-Screw Contact Force (N) | Average Threaded Carrier 2-Screw Contact Force (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 3333.90 | 3278.18 | 257.12 | 399.96 |

| 70 | 5819.23 | 5533.97 | 1627.89 | 1805.26 |

| 100 | 8330.07 | 7759.24 | 3405.57 | 3818.81 |

To further elaborate on the motion dynamics, I can derive additional formulas for the planetary roller screw assembly. For instance, the efficiency of the planetary roller screw assembly can be approximated by considering the friction losses at contact interfaces. The mechanical advantage is influenced by the helix angle and tooth geometry. A general expression for the transmission efficiency \(\eta\) might involve the ratio of output work to input work, accounting for friction coefficients at the roller-screw and roller-nut contacts. If \(\mu\) represents the effective friction coefficient, then for a screw-driven planetary roller screw assembly, the efficiency can be estimated as:

$$ \eta = \frac{\tan \lambda}{\tan(\lambda + \phi)} $$

where \(\phi = \arctan \mu\) is the friction angle. However, this is a simplified model; in reality, the planetary roller screw assembly has multiple contact points, complicating the efficiency calculation. Advanced modeling might incorporate the load distribution among rollers, which for a planetary roller screw assembly with \(N\) rollers, the load per roller \(F_{\text{roller}}\) under axial load \(F_{\text{axial}}\) can be expressed as:

$$ F_{\text{roller}} = \frac{F_{\text{axial}}}{N \cos \lambda \cos \tau} $$

assuming uniform load sharing. This formula highlights how the planetary roller screw assembly distributes loads across multiple rollers, enhancing its capacity. Moreover, the stiffness of the planetary roller screw assembly is crucial for precision applications. The axial stiffness \(k_{\text{axial}}\) can be derived from the contact stiffness at the interfaces. For a single roller-screw contact, the normal stiffness \(k_n\) relates to the material properties and contact geometry via Hertzian contact theory. For two bodies in contact with curvature radii \(R_1\) and \(R_2\), the contact stiffness per roller is:

$$ k_n = \frac{2E^* \sqrt{R^* \delta}}{3} $$

where \(E^*\) is the equivalent Young’s modulus, \(R^*\) is the equivalent radius, and \(\delta\) is the deformation. For the planetary roller screw assembly, the total axial stiffness involves summing contributions from all rollers in series and parallel combinations, leading to a complex expression that underscores the assembly’s robustness.

In terms of thermal effects, the planetary roller screw assembly may experience temperature rises due to friction, affecting clearance and accuracy. The heat generation rate \(Q\) can be approximated as:

$$ Q = \mu F_n v_{\text{slip}} $$

where \(v_{\text{slip}}\) is the slip velocity at contacts. Managing thermal expansion is vital for maintaining the performance of the planetary roller screw assembly in continuous operation. Additionally, wear in the planetary roller screw assembly is influenced by contact pressures and sliding distances. The Archard wear model provides a framework: wear volume \(V\) is proportional to load \(F_n\) and sliding distance \(s\), inversely proportional to hardness \(H\):

$$ V = k \frac{F_n s}{H} $$

where \(k\) is a wear coefficient. For the planetary roller screw assembly, optimizing material hardness and lubrication can extend service life. These aspects, while beyond the immediate scope, are integral to the holistic design of a planetary roller screw assembly.

Returning to the contact force analysis, the disparity between roller-nut and roller-screw contact forces in the planetary roller screw assembly can be attributed to the reaction forces from the threaded carrier. As external load increases, the threaded carrier engages more deeply, redirecting forces and causing the roller-nut interface to bear a higher proportion. This behavior has implications for fatigue life; since the roller-nut contact force is larger, that interface may be more prone to wear, necessitating enhanced material treatment or lubrication in the planetary roller screw assembly. Furthermore, the nonlinear increase in contact forces with load suggests that the planetary roller screw assembly exhibits some stiffness hardening, which is beneficial for maintaining accuracy under heavy loads. To visualize the force relationships, I can present another table summarizing the force components based on the earlier formulas. Assume typical values: \(\lambda = 6.81^\circ\), \(\tau = 30^\circ\) (since tooth angle is 60°), and axial force \(F_a = 1000 \, \text{N}\) for illustration. Then, using the equations:

$$ F_t = 1000 \tan(6.81^\circ) \approx 119.4 \, \text{N} $$

$$ F_r = 1000 \tan(30^\circ) \approx 577.4 \, \text{N} $$

$$ F_n = 1000 \sqrt{1 + \tan^2(6.81^\circ) + \tan^2(30^\circ)} \approx 1000 \sqrt{1 + 0.0142 + 0.3333} \approx 1160.5 \, \text{N} $$

For the roller-nut side, with \(F’_a = 1000 \, \text{N}\):

$$ F’_r = 1000 \tan(30^\circ) \approx 577.4 \, \text{N} $$

$$ F’_n = 1000 \sqrt{1 + \tan^2(30^\circ)} \approx 1000 \sqrt{1 + 0.3333} \approx 1154.7 \, \text{N} $$

This breakdown elucidates how forces are distributed in the planetary roller screw assembly. In practice, for the bearing-type planetary roller screw assembly, the presence of thrust cylindrical roller bearings alters force paths, potentially reducing \(F’_a\) and thus contact forces, but my simulation accounted for this. To generalize, the performance of a planetary roller screw assembly depends on numerous factors: number of rollers, pitch diameter ratios, helix angles, and lubrication conditions. Future work could explore optimizing these parameters for specific applications, such as high-speed or high-precision planetary roller screw assembly designs.

In conclusion, my analysis of the bearing-type planetary roller screw assembly has yielded several key insights. The derived theoretical formulas for motion parameters—such as angular velocities and axial displacement—align closely with dynamic simulation results, with relative errors within 2.13%, validating the kinematic model. The contact force study reveals that both roller-screw and roller-nut contact forces increase proportionally with external load, but the roller-nut interface consistently experiences higher forces, a gap that widens under heavier loads due to the involvement of the threaded carrier in the planetary roller screw assembly. Additionally, the threaded carrier-screw contact forces also rise with load, indicating load-sharing mechanisms. These findings emphasize the importance of considering contact force distributions in the design and maintenance of planetary roller screw assemblies to enhance durability and efficiency. For engineers, optimizing the tooth profiles, material selection, and preload in a planetary roller screw assembly can mitigate excessive contact stresses. Ultimately, the planetary roller screw assembly represents a sophisticated transmission solution, and continued research into its dynamics will further unlock its potential in advanced mechanical systems. I hope this comprehensive exploration serves as a valuable reference for those working with planetary roller screw assemblies, guiding improvements in performance and reliability.