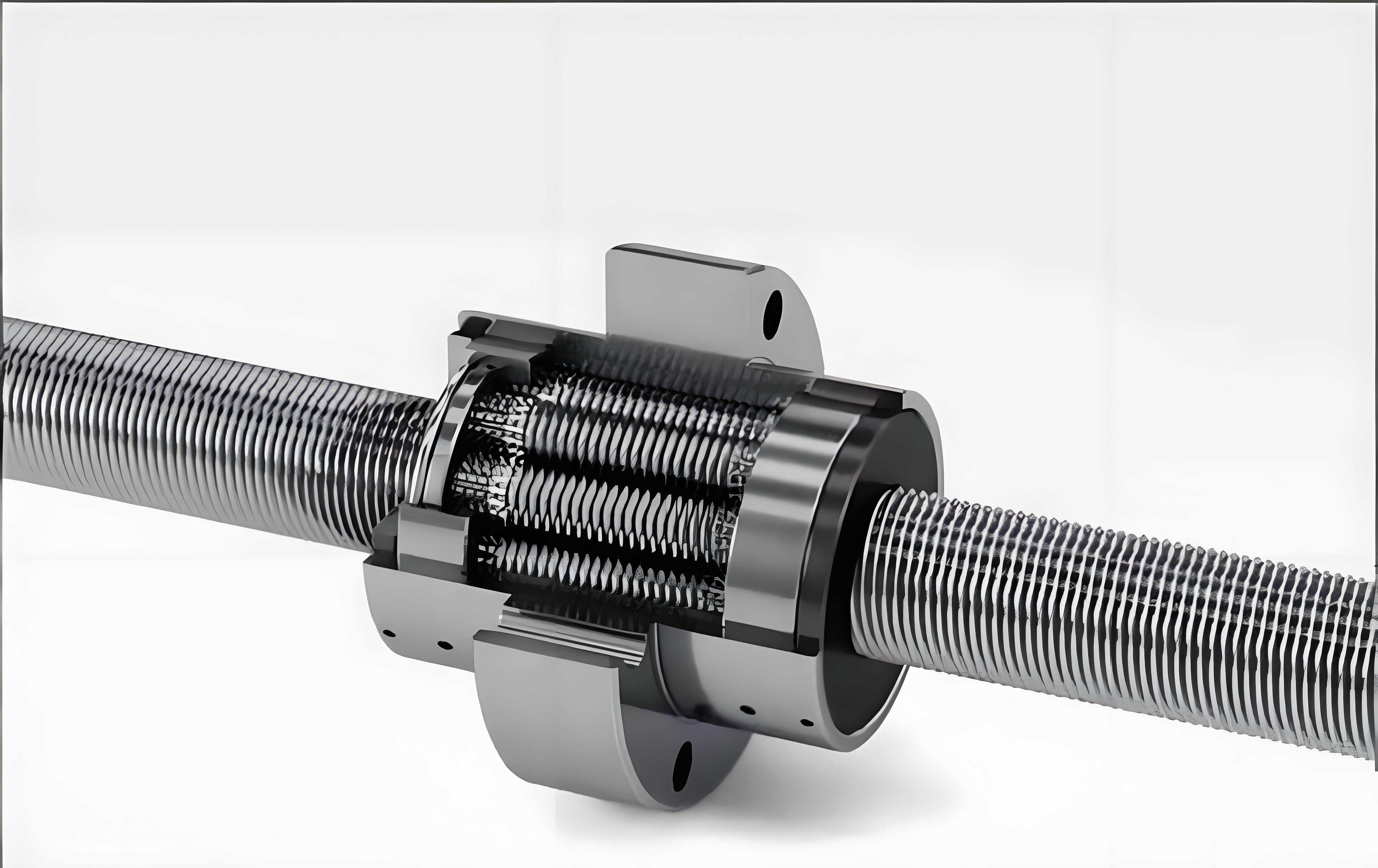

In this article, I explore the dynamic behavior of a planetary roller screw assembly, a critical component in linear electromechanical actuation systems. The planetary roller screw assembly offers high precision, long service life, substantial thrust capacity, and operational stability, making it indispensable in aerospace, defense, machine tools, and process control applications. However, accurately predicting its dynamic performance under various operational conditions requires a comprehensive model that accounts for multiple physical phenomena. Traditional methods, such as finite element analysis, can be computationally intensive and less adaptable for multi-domain simulations or parameter studies. Therefore, I employ bond graph theory to develop a dynamic characteristic model that integrates factors like transmission clearances, contact deformations at thread interfaces, torsional and compressive deformations of the screw, machining errors, load distribution among threads, friction effects including rolling and sliding, and inertial properties. This approach provides a modular, efficient, and versatile framework for analyzing the planetary roller screw assembly’s response, facilitating insights into its friction response and stiffness characteristics under dynamic loads.

The bond graph methodology is a powerful tool for modeling multi-energy domain systems, representing power flows through elements like sources, storage, dissipation, and transformation. For the planetary roller screw assembly, I construct a bond graph model that captures the energy interactions between mechanical rotational and translational domains. The model’s state equations are derived to simulate transient and steady-state behaviors. To ensure realism, I incorporate nonlinearities such as piecewise contact forces due to clearances and the LuGre friction model to depict stick-slip motion and Stribeck effects. Validation is performed by comparing step velocity responses with Adams software simulations, confirming the model’s accuracy. Subsequently, I investigate how screw rotational speed and slide-roll ratio influence friction force responses, and how transmission clearances and machining errors affect dynamic stiffness. The findings aim to enhance the dynamic accuracy and operational stability of planetary roller screw assemblies in practical applications.

To begin, let’s review the fundamental kinematics of a planetary roller screw assembly. The assembly consists of a central screw, multiple rollers arranged planetarily, and a nut. The screw typically rotates but does not translate axially, while the nut translates axially without rotation. The rollers both revolve around the screw axis (planetation) and rotate about their own axes (spin). For proper operation without slippage, geometric constraints must be satisfied. Denoting the pitch diameters at contact points as $d_S$ for the screw, $d_R$ for the roller, and $d_N$ for the nut, the relationship is:

$$ d_N = d_S + 2d_R $$

If the roller has a single-start thread, the number of starts for the screw and nut are given by:

$$ n_S = n_N = t + 2 \quad \text{where} \quad t = \frac{d_S}{d_R} $$

All threads are typically right-handed. Under these conditions, the kinematic relations are derived. The planetation angular velocity $\omega_e$ and roller spin angular velocity $\omega_R$ relate to the screw angular velocity $\omega_S$ as:

$$ \omega_e = \frac{\omega_S t}{2(t+1)} $$

$$ \omega_R = \frac{\omega_S t(t+2)}{2(t+1)} $$

The axial velocity $v$ of the nut and rollers is:

$$ v = \frac{n_S p \omega_S}{2\pi} $$

where $p$ is the thread pitch. These equations form the basis for transforming rotational motion to linear motion in the planetary roller screw assembly.

Next, I delve into modeling the friction at thread interfaces, a crucial aspect affecting dynamic performance. The friction between the screw-roller and roller-nut contacts involves both sliding and rolling components. I adopt the LuGre model to capture complex friction behaviors like static friction, Coulomb friction, viscous friction, and the Stribeck curve. The LuGre model describes the average bristle deflection $\beta$ at contacting surfaces:

$$ \dot{\beta} = v_r – \frac{k_0 |v_r|}{g(v_r)} \beta $$

where $v_r$ is the relative sliding velocity, $k_0$ is the bristle stiffness, and $g(v_r)$ is a function that models the Stribeck effect:

$$ g(v_r) = F_n \left[ \mu_c + (\mu_s – \mu_c) e^{-(v_r/v_s)^2} \right] $$

Here, $F_n$ is the normal contact force, $\mu_c$ is the dynamic friction coefficient, $\mu_s$ is the static friction coefficient, and $v_s$ is the Stribeck characteristic velocity. The friction force $F_L$ combines bristle deflection, damping, and viscous effects:

$$ F_L = k_0 \beta + k_1 \dot{\beta} + k_2 v_r $$

with $k_1$ as a damping coefficient and $k_2$ as a viscous friction coefficient. Additionally, rolling friction due to material hysteresis is considered as $F_{rr} = \mu_r F_n$, where $\mu_r$ is the rolling friction coefficient. In the bond graph, these friction elements are represented as modulated resistive elements (MR), with the normal force as the modulating signal.

The relative sliding velocities at interfaces need careful computation. For the screw-roller contact, analysis shows that sliding occurs primarily axially. The relative sliding velocity $v_{SR}$ is:

$$ v_{SR} = r_S \omega_S \tan(\lambda) \mathbf{k} $$

where $r_S$ is the screw contact radius, $\lambda$ is the helix angle, and $\mathbf{k}$ is the axial unit vector. This indicates that sliding is proportional to screw speed and helix angle. For the roller-nut contact, assuming perfect meshing with no slip due to gear rings at roller ends, the relative sliding velocity $v_{RN} = 0$, implying pure rolling. To incorporate these in the bond graph, transformers (TF) are used to convert angular velocities to linear sliding velocities. The slide-roll ratio, defined as the ratio of sliding to rolling components of screw angular velocity, influences friction response. If $\omega_{S1}$ is the screw angular velocity component corresponding to rolling, then:

$$ \omega_{S1} = \omega_S – \frac{2\pi \omega_S r_S \tan \lambda}{n_S p} $$

which relates to nut axial velocity $v$ as:

$$ \omega_{S1} = \frac{2\pi}{n_S p} \left(1 – \frac{2\pi r_S \tan \lambda}{n_S p}\right) v $$

This slide-roll ratio affects the friction dynamics significantly, as explored later.

Now, I address the force characteristics at thread interfaces, considering clearances and load distribution. The contact deformation between rollers and screw or nut threads is primarily Hertzian, with axial contact force $F_k$ related to axial deformation $\delta_j$ (where $j = s$ for screw or $n$ for nut) by:

$$ F_k = K \delta_j^{3/2} $$

where $K = k_j^{-3/2} (\sin \alpha \cos \lambda)^{5/2}$ is the axial contact stiffness, $k_j$ is the contact stiffness, and $\alpha$ is the contact angle. When accounting for unilateral transmission clearance $b$ and machining error $\sigma$, the effective clearance becomes $b + \sigma$. The contact force exhibits piecewise nonlinearity:

$$ F_k = \begin{cases}

K(z – b – \sigma)^{3/2}, & z \geq b + \sigma \\

0, & -b – \sigma < z < b + \sigma \\

K(z + b + \sigma)^{3/2}, & z \leq -b – \sigma

\end{cases} $$

where $z$ is the relative axial displacement. Similarly, the viscous damping force $F_R$ is:

$$ F_R = \begin{cases} c \dot{z}, & |z| \geq b + \sigma \\

0, & |z| < b + \sigma

\end{cases} $$

with $c$ as the damping coefficient. To model this piecewise behavior in bond graphs, I utilize switched power junctions, which allow activation of different force branches based on displacement thresholds. Boolean variables $u_i$ control the switching, ensuring only one branch is active at any time. For multiple engaged thread pairs, load distribution is considered by summing forces across $n$ threads. If $F_i$ is the force on the $i$-th thread pair, the total force $F$ is:

$$ F = \sum_{i=1}^n F_i $$

and the relative velocities are constrained by $ \dot{z}_i = \dot{z} $. This approach captures the non-uniform loading in a planetary roller screw assembly, enhancing model fidelity.

The screw itself contributes to system dynamics through torsional and compressive deformations. The torsional stiffness $K_1$ relates torque $T_S$ to twist angle $\phi$:

$$ T_S = K_1 \phi \quad \text{with} \quad K_1 = \frac{\pi G d_S^4}{32 l} $$

where $G$ is the shear modulus, $d_S$ is the screw diameter, and $l$ is the effective length. The axial compressive stiffness $K_2$ relates axial force $F_S$ to deformation $\epsilon$:

$$ F_S = K_2 \epsilon \quad \text{with} \quad K_2 = \frac{\pi d_S^2 E}{4 l} $$

where $E$ is Young’s modulus. In the bond graph, these are represented by capacitive elements (C) with appropriate stiffness parameters, storing potential energy and influencing the dynamic coupling between rotational and translational domains.

Integrating all components, I construct the overall bond graph model for the planetary roller screw assembly. The model is partitioned into five regions: (a) screw-side friction, torsional stiffness, and screw inertia; (b) screw-roller contact forces; (c) roller inertias for planetation and spin; (d) roller-nut contact forces; and (e) nut-side friction, compressive stiffness, and nut inertia. Key elements include effort sources (Se for axial load, Sf for screw angular velocity), inertial elements (I for masses and moments of inertia), resistive elements (R for damping and friction), capacitive elements (C for stiffness), and transformers (TF) for kinematic conversions. The state equations derived from the bond graph are:

$$ \begin{aligned}

F – F’ – \frac{\dot{P}_e \pi t}{n_S p (t+1)} – \frac{\dot{P}_R \pi (t+2)}{n_S p (t+1)} &= 0 \\

F’ – F_{Nr} \left(1 – \frac{2\pi r_S \tan \lambda}{n_S p}\right) \frac{\pi t(t+2)}{n_S p (t+1)} – F_a – \dot{P}_{NR} &= 0 \\

\dot{P}_S + F_{Sr} \left(1 – \frac{2\pi r_S \tan \lambda}{n_S p}\right) \frac{\pi t(t+2)}{2(t+1)} + F \frac{2\pi}{n_S p} + F_L r_S \tan \lambda – T_S &= 0 \\

T_S = K_1 \int_0^t \omega_S’ dt, \quad F_a = K_2 \int_0^t v’ dt \\

\dot{z} + \dot{z}’ + \frac{P_{NR}}{I_4} – \frac{1}{2\pi} \frac{P_S}{I_1} n_S p &= 0 \\

\dot{z} + \frac{P_e}{I_2} \frac{n_S p (t+1)}{\pi t} – \frac{P_R}{I_3} \frac{n_S p (t+1)}{\pi (t+2)} &= 0 \\

\omega – \omega_S’ – \frac{P_S}{I_1} = 0, \quad v – v’ – v_2 &= 0

\end{aligned} $$

where $F$ and $F’$ are contact forces on screw and nut sides, $P$ terms are momenta, $I$ terms are inertias, and other symbols as defined earlier. These equations are solved numerically to simulate dynamic responses.

To validate the bond graph model, I compare its predictions with a multi-body dynamics simulation in Adams software. For a specific planetary roller screw assembly with parameters listed in Table 1, I apply a step input of screw angular velocity $\omega_S = 62.8 \, \text{rad/s}$ under an axial load $F_a = 16,000 \, \text{N}$. The bond graph model neglects clearances and errors for this comparison to match Adams’ rigid-body assumption. The nut axial velocity response from both methods is plotted, showing excellent agreement: the rise phases align closely, and the steady-state mean velocities differ by only 0.5%. The bond graph model exhibits smoother settling due to incorporated contact damping, whereas Adams shows sharper transitions. This validates the bond graph model’s accuracy for dynamic analysis of planetary roller screw assemblies.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Screw pitch diameter | $d_S$ | 19.5 mm |

| Roller pitch diameter | $d_R$ | 6.5 mm |

| Nut pitch diameter | $d_N$ | 32.5 mm |

| Thread pitch | $p$ | 2 mm |

| Screw number of starts | $n_S$ | 5 |

| Roller number of starts | $n_R$ | 1 |

| Nut number of starts | $n_N$ | 5 |

| Number of engaged threads per roller | $n$ | 20 |

| Number of rollers | $N$ | 5 |

With the validated model, I proceed to analyze friction response characteristics. The LuGre model parameters are set as: $v_s = 0.001 \, \text{m/s}$, $k_0 = 10^5 \, \text{N/m}$, $k_1 = \sqrt{10^5} \, \text{N·s/m}$, $k_2 = 0.4 \, \text{N·s/m}$, $\mu_c = 0.3$, $\mu_s = 0.5$. I first investigate the effect of screw rotational speed on friction force response. Assuming a unilateral clearance $b = 0.02 \, \text{mm}$ and axial load $F_a = 1,600 \, \text{N}$, I simulate step inputs of $\omega_S$ at 12.5, 37.68, and 62.8 rad/s. The friction force (sum of sliding and rolling components) versus time is plotted. Results indicate that higher screw speeds lead to increased initial oscillations and faster response times. Specifically, increasing $\omega_S$ from 12.5 to 37.68 rad/s reduces response time by approximately 64%, while a further increase to 62.8 rad/s reduces it by about 40%. At steady state, friction forces converge to similar values. This is because higher speeds reduce the time for thread contact establishment and increase the average sliding velocity, causing the LuGre model’s friction coefficient to reach steady state quicker. The planetary roller screw assembly thus exhibits speed-dependent friction dynamics, which must be considered in control system design.

Next, I examine the influence of slide-roll ratio on friction response. Keeping $\omega_S = 62.8 \, \text{rad/s}$, $b = 0.02 \, \text{mm}$, and $F_a = 1,600 \, \text{N}$, I vary the slide-roll ratio from 0.1 to 0.5. The friction force response shows that higher slide-roll ratios amplify initial oscillations and accelerate response. Increasing the ratio from 0.1 to 0.3 cuts response time by roughly 60%, and from 0.3 to 0.5 by about 25%. Steady-state friction remains unchanged. This behavior stems from the enhanced sliding component, which elevates the average sliding velocity in the LuGre model, speeding up friction force buildup. For a planetary roller screw assembly operating under varying loads or speeds, managing the slide-roll ratio can help mitigate friction-induced vibrations and improve stability.

Now, I turn to stiffness characteristics, focusing on how transmission clearances and machining errors affect dynamic stiffness. Dynamic stiffness is defined as the ratio of applied axial force amplitude to resulting axial deformation amplitude under harmonic excitation. To study this, I fix the screw input ($\omega_S = 0$) and apply a harmonic axial force $F_a = 16,000 \sin(2\pi f t) \, \text{N}$, where $f$ is the frequency. I assume machining errors follow a normal distribution with zero mean and standard deviation $S_d = 0.44 \, \mu\text{m}$ (corresponding to IT5 grade). For different unilateral clearances $b = 0.01, 0.02, 0.03 \, \text{mm}$, I compute dynamic stiffness versus frequency. The results, summarized in Table 2, show that larger clearances reduce dynamic stiffness, especially at higher frequencies. For each clearance, stiffness initially rises with frequency but then slightly declines after a转折 point. For instance, with $b = 0.02 \, \text{mm}$, stiffness peaks around $f = 150 \, \text{Hz}$. Reducing clearance shifts this peak to higher frequencies: from 0.03 to 0.02 mm increases peak frequency by 16.7%, and from 0.02 to 0.01 mm increases it by 35.7%. This indicates that clearances dominate dynamic deformation at higher frequencies, so minimizing clearances is crucial for maintaining stiffness in high-frequency operations of planetary roller screw assemblies.

| Clearance $b$ (mm) | Peak Frequency (Hz) | Max Dynamic Stiffness (N/μm) | Stiffness at 500 Hz (N/μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 204 | 8.2 | 7.8 |

| 0.02 | 150 | 7.5 | 6.9 |

| 0.03 | 128 | 6.8 | 6.0 |

To quantify the impact of machining errors, I compare maximum roller contact deformations with and without errors. Let $\delta_{emax}$ be the maximum deformation with errors and $\delta_{max}$ without errors. For error standard deviations $S_d = 0.44, 0.75, 1.1 \, \mu\text{m}$ (IT5, IT6, IT7 grades), I compute the ratio $\delta_{emax}/\delta_{max}$ under varying axial load amplitudes. The results, presented in Table 3, demonstrate that machining errors always increase deformation (reduce stiffness), with more pronounced effects at lower loads. For example, at $F_a = 1,000 \, \text{N}$ and IT5 errors, deformation increases by 12%, whereas at $F_a = 10,000 \, \text{N}$, the increase is only 3%. Larger errors (IT7) exacerbate this reduction. This highlights the importance of precision manufacturing for planetary roller screw assemblies, especially in applications with light or fluctuating loads.

| Axial Load Amplitude $F_a$ (N) | $\delta_{emax}/\delta_{max}$ for IT5 ($S_d=0.44 \mu\text{m}$) | $\delta_{emax}/\delta_{max}$ for IT6 ($S_d=0.75 \mu\text{m}$) | $\delta_{emax}/\delta_{max}$ for IT7 ($S_d=1.1 \mu\text{m}$) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 1.12 | 1.21 | 1.32 |

| 5,000 | 1.05 | 1.09 | 1.14 |

| 10,000 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.08 |

In conclusion, the bond graph model developed for the planetary roller screw assembly provides a comprehensive and efficient tool for dynamic analysis. By incorporating key factors like clearances, contact deformations, friction, and errors, it accurately captures nonlinear behaviors. Validation against Adams confirms its reliability. The simulation studies reveal that screw speed and slide-roll ratio significantly influence friction response times and oscillations, with higher values accelerating response but increasing transient vibrations. Transmission clearances and machining errors detrimentally affect dynamic stiffness, particularly at higher frequencies and lower loads. Therefore, to enhance the dynamic accuracy and stability of planetary roller screw assemblies, designers should minimize clearances and errors, and consider friction characteristics in control algorithms. Future work could extend this model to include thermal effects or integrate it with actuator control systems for full electromechanical co-simulation. The versatility of bond graph theory makes it well-suited for such expansions, underscoring its value in advancing planetary roller screw assembly technology.

Throughout this article, I have emphasized the planetary roller screw assembly as a critical mechanical component, and the bond graph approach as a robust modeling framework. The insights gained from dynamic simulations can guide optimization efforts, leading to more reliable and high-performance linear actuation systems. As demand for precision motion control grows, continued research into the dynamic behavior of planetary roller screw assemblies will remain essential for innovation in aerospace, robotics, and industrial automation.