As a precision mechanical transmission device for converting rotary motion into linear motion, the planetary roller screw assembly distinguishes itself from other linear actuators through its unique meshing characteristics involving multiple threaded components. The superior load capacity, high reliability in harsh environments, and compact design of the planetary roller screw assembly have led to its widespread adoption in demanding applications such as aerospace actuators, robotics, and industrial machinery. The core of its operational performance lies in the intricate contact conditions between the screw, the planetary rollers, and the nut. Therefore, a deep understanding of the meshing principle, which governs the kinematic relationships, load distribution, contact stresses, and efficiency, is fundamental for the design, analysis, and optimization of the planetary roller screw assembly.

Structural Configuration and Meshing Characteristics

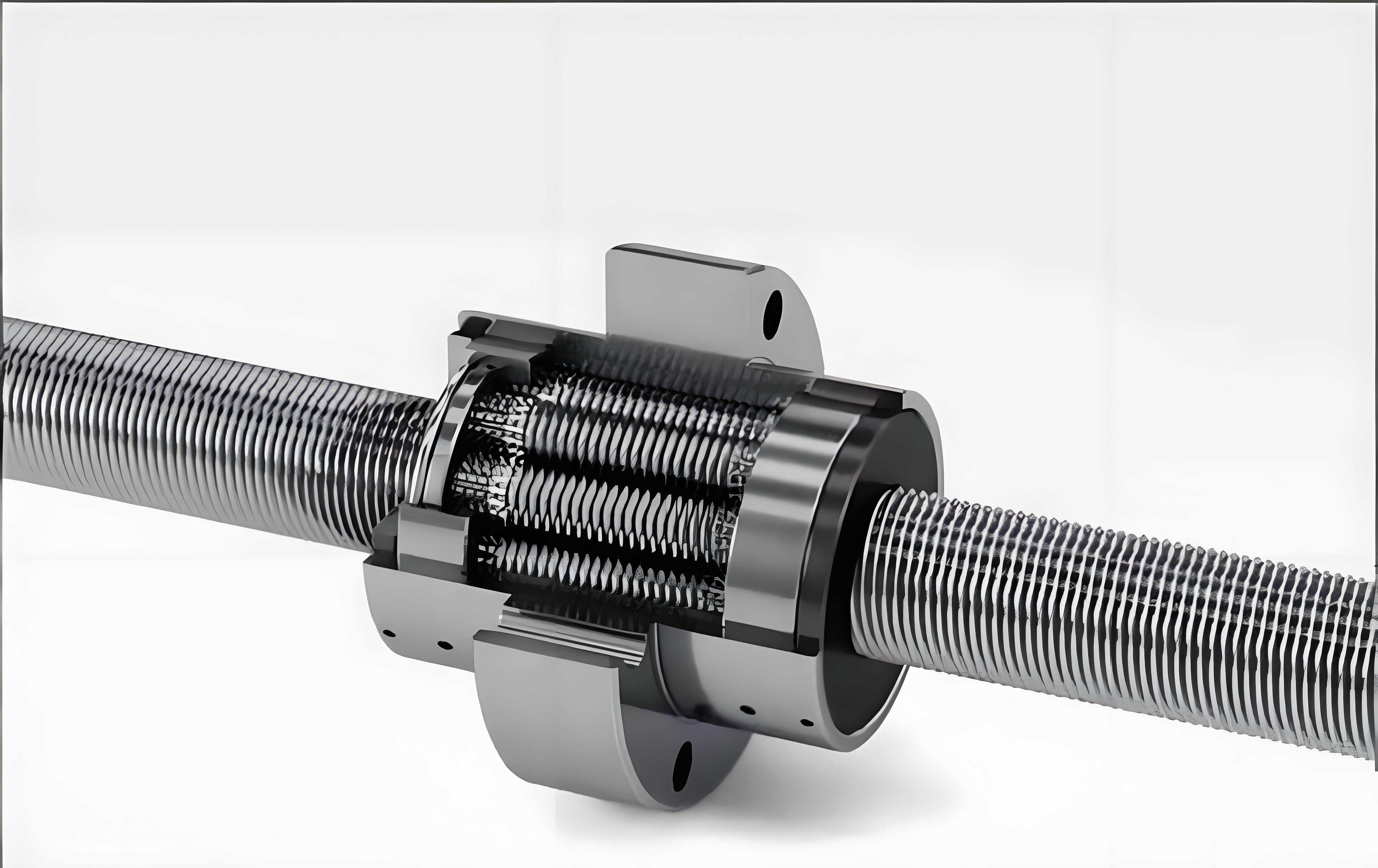

The fundamental components of a planetary roller screw assembly are the central screw, a set of planetary rollers distributed around it, and the enclosing nut. The screw and nut feature multi-start threads with the same hand (typically right-handed). In contrast, each planetary roller features a single-start external thread. The thread profiles are crucial: the screw and nut usually have trapezoidal or triangular profiles, while the rollers often have a circular-arc profile to reduce stress concentration and improve load-sharing. The rollers are retained within the assembly by guide mechanisms. Two primary configurations exist:

- Standard (or Rotary Screw) Configuration: The screw rotates, the nut is prevented from rotating and thus translates axially. The rollers’ axial movement is constrained by engagement of straight-sided (spur) gear teeth machined at their ends with an internal ring gear attached to the nut.

- Inverted (or Rotary Nut) Configuration: The nut rotates, the screw is prevented from rotating and translates axially. In this case, the screw has external gear teeth at its ends which engage with the spur gear teeth on the rollers to prevent their axial migration.

The meshing within a planetary roller screw assembly is a complex three-dimensional interaction involving multiple, simultaneous line contacts along helical paths. Unlike a ball screw where contact is theoretically point-based, the contact in a planetary roller screw assembly is a spatial curve, significantly increasing the contact area and thus the load capacity. The meshing can be characterized by the projection of contact points onto a plane perpendicular to the screw axis.

Consider a standard planetary roller screw assembly with right-handed threads. When the nut is loaded in one axial direction (e.g., negative Z-direction), specific flanks of the threads come into contact: the lower flank of the nut thread meshes with the upper flank of the roller thread, while the upper flank of the screw thread meshes with the lower flank of the same roller thread. This contact pattern reverses when the load direction changes. The geometry dictates that the contact points between the screw and roller do not lie in the plane containing both their axes. Due to the external meshing of two right-handed threads, their thread tangents at the contact point in a radial section appear crossed. Conversely, for the nut and roller pair (internal-external meshing), the thread tangents in a radial section are parallel. This is reversed for the inverted configuration.

The position of a contact point for any pair can be described by its radial distance from the component’s axis (the contact radius, \( r_c \)) and its angular position relative to a reference plane (the contact angle, \( \phi_c \)). For a screw-roller pair, we denote these as \( r_{Sc}, \phi_{Sc} \) and \( r_{Rsc}, \phi_{Rsc} \). For a nut-roller pair, they are \( r_{Nc}, \phi_{Nc} \) and \( r_{Rnc}, \phi_{Rnc} \). The contact radii are bounded by the root and crest radii of the mating threads. Under ideal conditions and perfect geometry, these contact parameters remain constant during operation, defining the fundamental meshing geometry of the planetary roller screw assembly.

Fundamentals and Existing Methods for Meshing Analysis

The meshing principle for a planetary roller screw assembly is essentially an application of spatial gearing theory to helical surfaces with modified profiles. The primary goal is to determine the precise location of contact points (or lines) under load, the condition for conjugate action, and the resulting kinematic relations. The analysis is complicated by the multi-body nature, the thread profile modifications (like the circular arc on the roller), and the need to satisfy meshing conditions for both screw-roller and nut-roller pairs simultaneously.

Mathematical Representation of Helical Surfaces

The foundation of any meshing analysis is a precise mathematical model of the contacting surfaces. The thread surface of each component in a planetary roller screw assembly is a helical surface generated by sweeping a profile curve along a helix. Let us define a coordinate system \( O-xyz \) fixed to the screw, with the \( z \)-axis along the screw axis. A point on the screw thread surface \( \Sigma_S \) can be expressed as:

$$ \mathbf{r}_S(u, \theta) = \begin{bmatrix}

x_S(u, \theta) \\

y_S(u, \theta) \\

z_S(u, \theta)

\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}

r_S(u) \cos(\theta + \phi_S) \\

r_S(u) \sin(\theta + \phi_S) \\

\frac{L_S}{2\pi} \theta + p_S(u)

\end{bmatrix} $$

Here, \( u \) is the profile parameter, \( \theta \) is the angular screw rotation parameter, \( L_S \) is the lead of the screw, \( \phi_S \) is a phase angle, \( r_S(u) \) defines the radial distance of the profile point, and \( p_S(u) \) defines its axial position within one thread turn. Similar equations can be formulated for the roller surface \( \Sigma_R \) and the nut surface \( \Sigma_N \) in their own body-fixed coordinate systems, which must then be transformed into the common screw coordinate system for meshing analysis.

The unit normal vector \( \mathbf{n} \) to the surface is critical for contact analysis and is given by:

$$ \mathbf{n}(u, \theta) = \frac{\frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial u} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial \theta}}{\left\| \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial u} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial \theta} \right\|} $$

Review of Established Meshing Point Solution Methods

Researchers have developed several approaches to solve for the contact conditions in a planetary roller screw assembly. These methods vary in complexity and underlying assumptions.

| Method Category | Core Principle | Key Steps / Equations | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 2D Section-Based Method | Discretizes the 3D contact problem into multiple 2D cross-sections. |

|

Advantage: Intuitive, directly provides axial clearance. Limitation: Computationally intensive, accuracy depends on section density; less formal meshing theory. |

| 2. Space Curve (Frenet Frame) Based Method | Uses the differential geometry of the mean helix and the thread profile in the normal plane. |

|

Advantage: Elegant, based on solid differential geometry; good for near-nominal contact radii. Limitation: Deriving explicit flank clearance can be indirect; assumes contact occurs near the pitch helix. |

| 3. Full Helical Surface Based Method | Directly applies the theory of gearing and the condition of continuous tangency between parameterized surfaces. |

|

Advantage: Most rigorous and comprehensive; can account for full profile geometry and clearance; foundational for advanced analysis. Limitation: Leads to complex systems of nonlinear equations; requires careful numerical solution. |

The surface-based method is considered the most fundamental for developing a complete meshing theory for the planetary roller screw assembly. Based on this approach and applying the conditions of coordinate coincidence and collinear normals for the screw-roller pair in a standard configuration, a simplified yet comprehensive set of meshing equations can be derived. For a screw flank and a roller flank in contact, these equations are:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& r_{Sc}\cos \phi_{Sc} = – r_{Rsc}\cos(\phi_{Rsc}) + r_{S0} + r_{R0} \\

& r_{Sc}\sin \phi_{Sc} = r_{Rsc}\sin \phi_{Rsc} \\

& \cos \phi_{Sc} \tan \beta_{S0} + \sin \phi_{Sc} \tan \lambda_{Sc} = \cos \phi_{Rsc} \tan \beta_{Rsc} + \sin \phi_{Rsc} \tan \lambda_{Rsc} \\

& \sin \phi_{Sc} \tan \beta_{S0} – \cos \phi_{Sc} \tan \lambda_{Sc} = -\sin \phi_{Rsc} \tan \beta_{Rsc} + \cos \phi_{Rsc} \tan \lambda_{Rsc}

\end{aligned}

$$

Where \( r_{S0}, r_{R0} \) are the nominal (pitch) radii, \( \beta_{S0} \) is the screw flank angle, \( \lambda_{Sc} = \arctan(L_S / (2\pi r_{Sc})) \) is the lead angle at the contact radius on the screw, and \( \lambda_{Rsc} = \arctan(L_R / (2\pi r_{Rsc})) \) is the corresponding lead angle on the roller. The effective flank angle \( \beta_{Rsc} \) on the roller’s circular-arc profile at the contact point is a function of the roller’s nominal flank angle \( \beta_{R0} \), its arc radius \( r_{pR} \), and the contact radius \( r_{Rsc} \):

$$ \tan \beta_{Rsc} = \frac{r_{Rsc} – r_{R0} + r_{pR} \sin \beta_{R0}}{\sqrt{r_{pR}^2 – (r_{Rsc} – r_{R0} + r_{pR} \sin \beta_{R0})^2}} $$

A similar set of four equations can be derived for the nut-roller pair. Solving these eight nonlinear equations simultaneously for the eight unknowns (\( r_{Sc}, \phi_{Sc}, r_{Rsc}, \phi_{Rsc}, r_{Nc}, \phi_{Nc}, r_{Rnc}, \phi_{Rnc} \)) defines the complete meshing geometry of the planetary roller screw assembly under no-load or ideal conditions.

Parameter Interdependence and Design Considerations

The performance of a planetary roller screw assembly is highly sensitive to the relationships between its numerous design parameters. The meshing equations explicitly reveal these dependencies. Key parameter groups include:

| Parameter Group | Typical Symbols | Influence on Meshing & Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Lead / Pitch Parameters | \( L_S, L_R, L_N \), Number of starts \( N_S \) | Determine the transmission ratio \( i = L_S / (2\pi) \) for standard config. For kinematic consistency, the relationship \( L_S = L_R + L_N \) must hold for a standard planetary roller screw assembly (with \( L_R \) and \( L_N \) having the same sign). Violation causes axial migration of rollers. |

| Nominal (Pitch) Radii | \( r_{S0}, r_{R0}, r_{N0} \) | Define the basic size and gear ratio between components. The nominal center distance is \( r_{S0} + r_{R0} = r_{N0} – r_{R0} \). They directly influence the contact radii and load distribution. |

| Thread Profile Parameters | Flank angles \( \beta_{S0}, \beta_{N0}, \beta_{R0} \); Roller arc radius \( r_{pR} \) | Critical for contact stress, load capacity, and friction. The circular arc profile on the roller modifies the effective pressure angle at the contact point, affecting the normal force vector and its components. |

| Clearance / Preload | Axial flank clearance \( \delta_a \), Diametral clearance | Essential for assembly and lubrication but causes backlash. Preload (negative clearance) eliminates backlash at the cost of increased friction, heat generation, and reduced efficiency. The meshing equations can be adapted to model a specified clearance. |

The contact radii \( r_c \) solved from the meshing equations are generally not equal to the nominal pitch radii \( r_0 \). This deviation is a fundamental characteristic of the planetary roller screw assembly with profile-modified rollers. It means the effective lead angles at the contact points differ from those calculated at the pitch diameters, slightly affecting the kinematic relationship. Furthermore, this deviation influences the lever arm for friction and the load distribution among the multiple rollers and thread turns, making its accurate calculation vital for predicting stiffness and life.

Kinematic and Dynamic Analysis Rooted in Meshing Theory

The meshing conditions directly determine the kinematic relationships and form the basis for dynamic modeling of the planetary roller screw assembly.

Kinematics and the “Steady-State Velocity Ratio”

For a standard planetary roller screw assembly with a rotating screw and translating nut, the primary kinematic relationship is between the screw angular velocity \( \omega_S \) and the nut translational velocity \( v_N \). In an ideal, no-slip condition, this is given by the screw lead: \( v_N = \frac{L_S}{2\pi} \omega_S \). However, the more intricate kinematics involve the roller motion. The meshing conditions enforce specific angular velocity relationships. Considering the screw-roller contact at radius \( r_{Sc} \) and the roller-nut contact at radius \( r_{Rnc} \), the condition of no gross sliding at the contact points (pure rolling condition) leads to the following velocity relations:

$$ \omega_R \cdot r_{Rsc} = \omega_S \cdot r_{Sc} \quad \text{(at screw-roller contact)} $$

$$ \omega_R \cdot r_{Rnc} = \omega_N \cdot r_{Nc} \quad \text{(at nut-roller contact, where } \omega_N=0 \text{ for standard config)} $$

Since the nut is stationary in rotation (\( \omega_N = 0 \)), the second equation implies \( \omega_R = 0 \) if \( r_{Rnc} \neq 0 \). This is a contradiction because the rollers obviously orbit. The resolution is that the rollers undergo a complex motion composed of rotation about their own axis (\( \omega_R \)) and revolution around the screw axis (\( \omega_{carrier} \)). The correct kinematic constraint comes from the relative velocity at the contact points being zero along the common normal. A comprehensive analysis yields the steady-state angular velocity ratio between the screw and the roller’s absolute rotation:

$$ \frac{\omega_R}{\omega_S} = \frac{r_{Sc} \sin \lambda_{Sc} – r_{Rsc} \sin \lambda_{Rsc}}{r_{Rsc} \sin \lambda_{Rsc} – r_{Rnc} \sin \lambda_{Rnc}} \cdot \frac{\cos(\phi_{Rsc} – \phi_{Rnc})}{\cos(\phi_{Sc} – \phi_{Rsc})} $$

This ratio depends explicitly on the contact geometry parameters (\( r_c, \phi_c, \lambda_c \)) derived from the meshing theory. Deviations from the designed nominal geometry due to manufacturing tolerances or load-induced deflections will cause this ratio to vary, potentially inducing parasitic sliding and affecting efficiency.

Dynamics, Load Distribution, and Friction

The dynamic model of a planetary roller screw assembly must account for inertias, time-varying meshing stiffness, and friction at the multiple contact lines. The foundation is the static load distribution, which determines how an external axial force \( F_a \) on the nut is shared among the \( Z \) rollers and the \( N \) active thread turns engaged with each roller.

Assuming linear contact mechanics (Hertzian theory for line contact), the normal load \( Q_{ij} \) at the \( j \)-th turn of the \( i \)-th roller can be related to the local approach \( \delta_{ij} \) by a stiffness constant \( K \): \( Q_{ij} = K \delta_{ij}^{n} \) (where \( n \approx 0.9 \) for line contact). The total approach is the sum of the axial displacement at that turn due to the nut’s position and the elastic deformations. The equilibrium condition is:

$$ F_a = \sum_{i=1}^{Z} \sum_{j=1}^{N} Q_{ij} \cdot \left( \tan \lambda_{c,ij} \pm \mu \frac{\sec \beta_{c,ij}}{\cos \lambda_{c,ij}} \right) $$

The sign in the bracket depends on the direction of motion and load. The lead angle \( \lambda_c \) and pressure angle \( \beta_c \) at each contact point are, again, outputs of the meshing analysis. Friction, represented by the coefficient \( \mu \), is a major source of torque loss and heat generation in the planetary roller screw assembly. The friction torque \( T_f \) on the screw is:

$$ T_f = \sum_{i=1}^{Z} \sum_{j=1}^{N} Q_{ij} \cdot \left( \frac{r_{Sc,ij} \cdot \mu \sec \beta_{Sc,ij}}{\cos \lambda_{Sc,ij}} \pm \frac{L_S}{2\pi} \right) $$

This shows how the contact radius \( r_{Sc} \) directly scales the frictional torque. The efficiency \( \eta \) of the planetary roller screw assembly can then be derived as the ratio of useful output power (\( F_a \cdot v_N \)) to input power (\( T_{in} \cdot \omega_S \)), where \( T_{in} = T_f + T_{ideal} \) and \( T_{ideal} = F_a \cdot L_S / (2\pi) \).

$$ \eta = \frac{1}{1 + \frac{2\pi}{L_S} \cdot \frac{T_f}{F_a}} $$

The dynamic equations of motion for each component (screw, nut, rollers) can be formulated using Lagrange’s method or Newton-Euler equations, incorporating the meshing forces derived above as internal constraints. This leads to a complex multi-body dynamic system that can predict vibrations, resonance frequencies, and transient response, which are crucial for high-performance applications of the planetary roller screw assembly.

Future Research Directions and Concluding Remarks

While significant progress has been made in understanding the planetary roller screw assembly, the meshing theory and its applications continue to offer rich avenues for research to meet the demands of next-generation precision systems.

- Meshing under Realistic Conditions: Current models largely assume perfect geometry. Future work must integrate the effects of manufacturing tolerances (lead error, profile error, pitch diameter variation) and assembly errors (misalignment, eccentricity) into the meshing equations. This will allow for predicting the statistical variation in backlash, stiffness, and the kinematic error of the planetary roller screw assembly.

- Coupled Spur-Helical Meshing Analysis: The end-gear teeth (spur) and the thread (helical) meshing in a planetary roller screw assembly are mechanically coupled but often analyzed separately. A unified model that simultaneously satisfies the meshing conditions for both gear pairs and the thread pairs is needed to accurately predict roller migration, dynamic coupling, and the true constraints on the roller’s motion, especially during reversal or under high acceleration.

- Advanced Dynamics and Elastodynamics: Developing high-fidelity nonlinear dynamic models that include time-varying meshing stiffness (from the varying number of engaged teeth/threads), clearance nonlinearity, and thermo-elastic effects. This is essential for simulating the performance of a planetary roller screw assembly in high-speed, high-frequency reciprocating applications common in modern automation and robotics.

- Integrated Tribo-Dynamic Models: Friction is a dominant factor affecting efficiency, heat generation, and wear. Research should focus on developing models that couple the dynamics with advanced tribological models (mixed/EHL lubrication regimes) for the thread contacts, enabling life prediction and lubrication optimization for the planetary roller screw assembly.

- Topology Optimization for Performance: Using the meshing theory and finite element analysis as a foundation, apply topology and shape optimization techniques to explore novel thread profile geometries (beyond circular arcs) for objectives like minimized friction, maximized stiffness-to-weight ratio, or improved load distribution in a planetary roller screw assembly.

In conclusion, the meshing principle is the cornerstone for analyzing and designing the planetary roller screw assembly. From the basic geometry of helical surfaces to the complex coupled dynamics, a thorough grasp of how the screw, rollers, and nut interact is indispensable. The progression from simplified 2D sections to full surface-based meshing equations represents an evolution towards greater rigor and predictive capability. As applications for the planetary roller screw assembly push the boundaries of speed, precision, and load, future research must refine these models to account for real-world imperfections, complex dynamic interactions, and advanced material and lubrication behavior, ensuring this versatile mechanism continues to meet the challenges of advanced mechanical systems.