In modern high-performance aerospace, automotive, and industrial automation systems, the demand for reliable, efficient, and high-power-density actuation solutions has never been greater. Among the various technologies vying to replace traditional hydraulic systems, the Electro-Mechanical Actuator (EMA) stands out for its potential to reduce system weight, increase efficiency, simplify maintenance, and enhance overall reliability. At the heart of a high-performance EMA lies the critical power transmission component responsible for converting the rotary motion of an electric motor into precise linear force and displacement. While ball screw mechanisms have been widely used, the planetary roller screw assembly represents a superior alternative for demanding applications due to its higher load capacity, greater stiffness, longer life, and superior shock load tolerance.

This article presents a comprehensive dynamic analysis of an EMA system centered around a standard planetary roller screw assembly. I will develop a detailed nonlinear mathematical model that accounts for real-world installation conditions and aerodynamic load interactions, focusing on the impact of key nonlinearities—specifically structural compliance, friction, and mechanical backlash—on the system’s transient and steady-state performance. The analysis employs simulation to quantify these effects and validates the model’s fidelity against performance requirements.

System Architecture and Working Principle

A typical EMA deployed in a flight control surface actuation loop consists of several key subsystems integrated into a cohesive unit. The primary components include:

- Brushless DC Motor: Provides the motive torque, driven by a high-voltage DC bus (e.g., 270V).

- Electronic Controller: Houses the power electronics and control algorithms. It typically implements a cascaded control structure with inner current and speed loops and an outer position loop.

- Gear Reducer: A precision gearbox used to increase the output torque from the motor and match the optimal speed range for the screw mechanism.

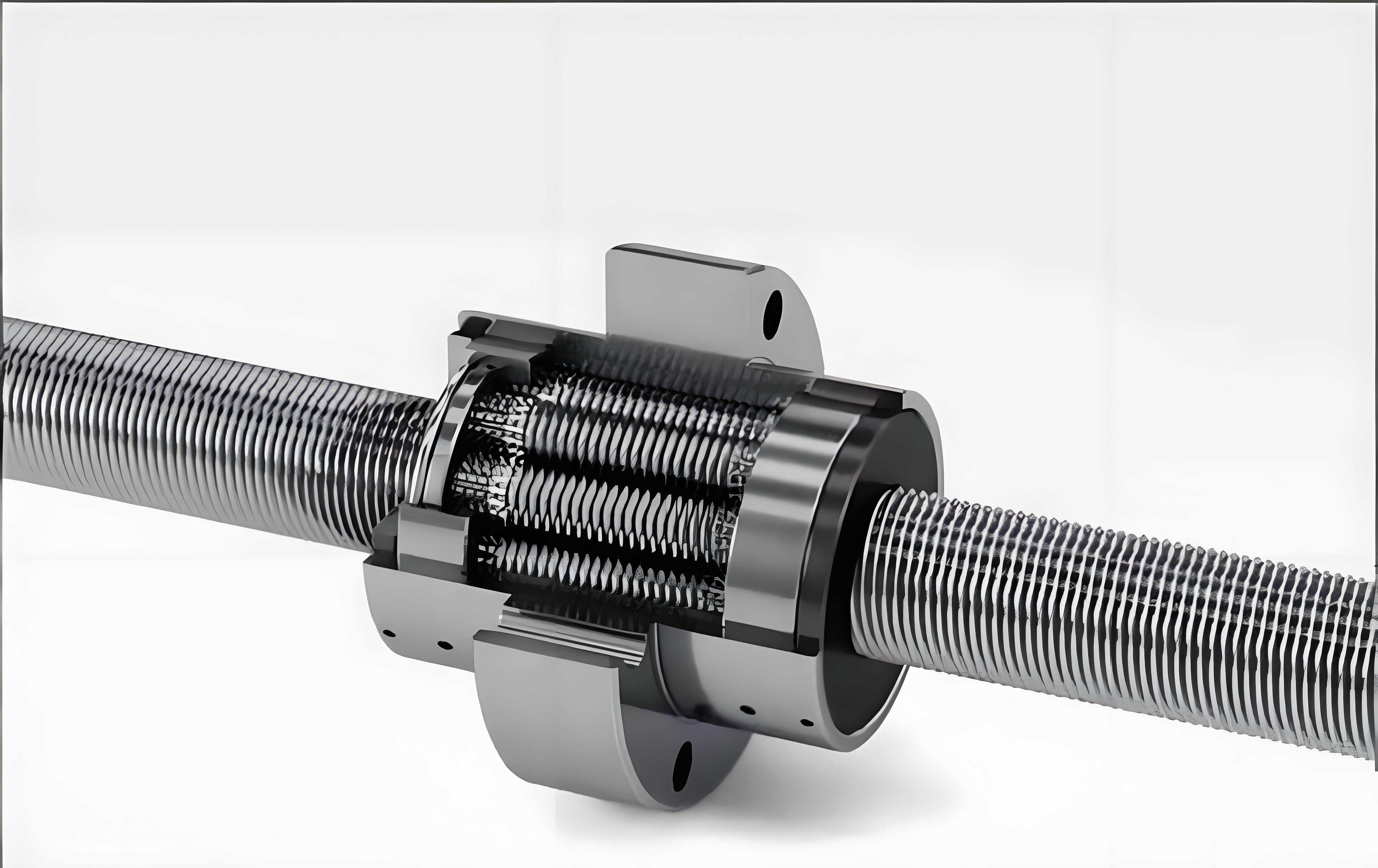

- Planetary Roller Screw Assembly (PRSA): The core actuator element. It transforms the rotational motion from the gearbox into linear motion of an output rod. The standard planetary roller screw assembly configuration utilizes multiple threaded rollers distributed around a central threaded screw. The rollers mesh with both the screw and a stationary nut, providing a large number of load-bearing contact points, which is the source of its high performance.

The operational principle is as follows: A position command from the flight control computer is received by the EMA’s controller. The controller processes this command through its position, speed, and current control loops to generate the appropriate voltage signals for the motor. The motor rotates, and its output is geared down by the reducer. This rotation is imparted to the screw of the planetary roller screw assembly. As the screw rotates, the interaction between the screw threads, the planetary rollers, and the fixed nut forces the screw (or a translating nut, depending on design) to move linearly. This linear motion is transferred via the output rod and a linkage (e.g., a lever arm) to deflect the control surface. Continuous feedback from motor current, motor shaft speed, and output rod position ensures accurate closed-loop tracking of the commanded surface deflection against varying aerodynamic loads.

Mathematical Modeling of the EMA System

To accurately predict and analyze dynamic behavior, a multi-domain model integrating electrical, mechanical, and control elements is essential. The model must account for the system’s connection to the airframe structure and the aerodynamic load.

1. Motor and Controller Model

The brushless DC motor is modeled using its equivalent circuit. The relationship between the commanded voltage \(V_c\) from the controller and the armature current \(I_c\) is given by a first-order transfer function, incorporating back-EMF:

$$I_c = G_e (V_c – K_{\omega} \omega_m)$$

where \(G_e = \frac{1/R_c}{(L_c/R_c)s + 1} = \frac{1/R_c}{\tau_e s + 1}\). Here, \(\omega_m\) is the motor angular velocity, \(K_{\omega}\) is the back-EMF constant, \(R_c\) is the winding resistance, \(L_c\) is the winding inductance, and \(\tau_e\) is the electrical time constant.

The electromagnetic torque produced by the motor is:

$$T_m = K_t I_c$$

where \(K_t\) is the motor torque constant. The motor’s equation of motion, considering the reflected load from the transmission, is:

$$T_m = J_m \dot{\omega}_m + B_m \omega_m + \frac{T_{load}}{i}$$

In this equation, \(J_m\) is the total inertia reflected to the motor shaft, \(B_m\) is the viscous friction coefficient, \(T_{load}\) is the load torque seen by the motor after the transmission, and \(i\) is the total gear ratio (product of gearbox ratio and the planetary roller screw assembly lead-related ratio).

The controller implements a cascaded control strategy. The inner loops ensure stable force generation and speed control, while the outer loop provides position tracking.

- Current Loop: A fast PI controller regulates the motor current, which is proportional to torque. This loop compensates for electrical dynamics and provides overload protection.

- Speed Loop: A PI controller processes the error between the commanded speed (from the position loop) and the measured motor speed.

- Position Loop: A proportional (P) controller is often sufficient for the outer loop, generating the speed command based on the position error.

Saturation blocks for voltage and current are critical to model real-world power electronics limitations.

2. Planetary Roller Screw Assembly and Transmission Model

The planetary roller screw assembly model must capture its dual function: motion transformation and force amplification. The fundamental kinematic relationship is:

$$v_{rod} = \frac{l}{2\pi} \omega_{screw}$$

$$F_{rod} = \frac{2\pi \eta}{l} T_{screw}$$

where \(v_{rod}\) is the output rod linear velocity, \(\omega_{screw}\) is the angular velocity of the screw, \(l\) is the lead of the planetary roller screw assembly, \(F_{rod}\) is the output force, \(T_{screw}\) is the input torque, and \(\eta\) is the mechanical efficiency.

The load torque reflected to the motor shaft through the planetary roller screw assembly and gearbox is:

$$T_{load} = \frac{F_{ext} \cdot l}{2\pi i_{prs} \eta}$$

where \(F_{ext}\) is the external force on the rod (from aerodynamic load and inertia), and \(i_{prs}\) is the kinematic ratio of the screw (\(2\pi/l\)).

Friction Model

Friction within the planetary roller screw assembly, bearings, and seals is a dominant nonlinearity. A comprehensive model accounting for Coulomb, viscous, and Stribeck effects, as well as load dependence, is used. The total friction torque \(T_{fric}\) at the motor shaft can be expressed as:

$$T_{fric} = \left[ T_c + T_s e^{-|\omega_m|/\omega_s} + |T_{load}| (c + d \cdot \text{sgn}(\omega_m T_{load})) \right] \cdot \text{sgn}(\omega_m)$$

where \(T_c\) is Coulomb friction torque, \(T_s\) is Stribeck friction torque, \(\omega_s\) is the Stribeck velocity, and \(c\), \(d\) are coefficients modeling the influence of the load torque on friction. This model is implemented as a three-port element taking speed and load torque as inputs.

Backlash (Gap) Model

Mechanical backlash arising from tolerances and wear in the gears and the planetary roller screw assembly is modeled as a dead zone in the angular transmission path. For a transmitted torque \(T_{trans}\) through a shaft with stiffness \(k_s\) and total backlash angle \(2\alpha\):

$$

T_{trans} =

\begin{cases}

k_s(\theta_d – \alpha) + c \dot{\theta}_d, & \theta_d > \alpha \\

0, & |\theta_d| \le \alpha \\

k_s(\theta_d + \alpha) + c \dot{\theta}_d, & \theta_d < -\alpha

\end{cases}

$$

where \(\theta_d = \theta_{in} – \theta_{out}\) is the angular displacement difference across the gap, and \(c\) is an associated damping coefficient.

3. Structural Compliance Model

The assumption of infinitely rigid mounts and connections is invalid for high-performance actuation. Two primary compliances are modeled:

- Anchorage Stiffness (\(K_{Z1}\)): The stiffness of the interface between the EMA housing and the airframe structure.

- Transmission Stiffness (\(K_{Z2}\)): The combined stiffness of the output rod, linkages, and lever arm connecting the EMA rod to the control surface.

These are modeled as linear spring-damper elements in series with the actuator output force and the aerodynamic load mass. The equivalent series stiffness \(K_{eq}\) significantly influences the system’s lowest mechanical resonant frequency:

$$\frac{1}{K_{eq}} = \frac{1}{K_{Z1}} + \frac{1}{K_{Z2}} + \frac{1}{K_{Z3}}$$

where \(K_{Z3}\) might represent other internal compliances (e.g., nut-to-rod connection). The resonant frequency \(f_{res}\) is then approximately:

$$f_{res} = \frac{1}{2\pi} \sqrt{\frac{K_{eq}}{m_{load}}}$$

where \(m_{load}\) is the effective mass of the control surface.

4. Aerodynamic Load Model

The control surface is modeled as a rotational inertia \(J_{rud}\) subject to aerodynamic hinge moments. For dynamic analysis, this can be simplified to an equivalent linear mass-spring-damper system driven by the EMA output rod position, or more accurately, as a planar mechanism where aerodynamic force is applied at a pressure center, creating a load proportional to dynamic pressure and surface deflection.

Analysis of Nonlinear Effects on Dynamic Characteristics

Using the developed model, I systematically analyze the impact of key nonlinear parameters. The baseline system parameters are summarized in the table below.

| Parameter Group | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor & Control | Winding Resistance, \(R_c\) | 1.0 | Ω |

| Back-EMF Constant, \(K_{\omega}\) | 0.25 | V/(rad/s) | |

| Torque Constant, \(K_t\) | 0.179 | Nm/A | |

| Rotor Inertia, \(J_m\) | 0.001 | kg·m² | |

| Current Limit | ±70 | A | |

| Position Loop Gain | 143 | – | |

| Transmission | Gearbox Ratio | 3.33 | – |

| Planetary Roller Screw Assembly Lead, \(l\) | 2 | mm | |

| PRSA Contact Stiffness | 1×10⁸ | N/m | |

| Total Transmission Ratio, \(i\) | ~10,000 | rad/m | |

| Structure | Anchorage Stiffness, \(K_{Z1}\) | 1.4×10⁷ | N/m |

| Transmission Stiffness, \(K_{Z2}\) | 1.4×10⁷ | N/m | |

| Output Rod Mass | 5 | kg | |

| Housing Mass | 20 | kg | |

| Load | Control Surface Inertia | 20 | kg·m² |

| Equivalent Load Mass | 2000 | kg |

1. Impact of Mechanical Backlash

Backlash, primarily from the gearbox and the planetary roller screw assembly, introduces a dead zone that severely degrades positioning accuracy and can induce limit-cycle oscillations. The effect of varying backlash levels on the step response is analyzed.

| Backlash (mm) | Settling Time | Overshoot | Steady-State Error | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.002 | Moderate | Small | Negligible | Minor oscillation on reversal. |

| 0.02 | Increased | Pronounced | Noticeable | Clear post-impact oscillation, reduced stability margin. |

| 0.05 | Significantly Increased | Large | Significant | Severe ringing and poor stability, especially after a load disturbance. |

The simulation clearly shows that increasing backlash amplitude leads to larger and more persistent oscillations in the step response, particularly when the actuator reverses direction to correct its position. This nonlinearity directly limits bandwidth and precision. Mitigation strategies include the use of anti-backlash gears, preloading the planetary roller screw assembly, and employing advanced control techniques like adaptive backlash compensation.

2. Impact of Friction Nonlinearity

Friction causes static error (dead-band) and can lead to stick-slip motion at low speeds. Comparing the step response with and without the detailed friction model reveals its effect.

- Without Friction Model: The system responds quickly with minimal steady-state error, representing an idealized case.

- With Friction Model: The response shows increased rise time, a slight reduction in overshoot due to damping, but a distinct steady-state position error. The actuator “gets stuck” short of the commanded position because the control effort must first overcome static friction.

To counteract this, a force closed-loop feedback strategy is implemented. A force sensor in the load path provides feedback, allowing the controller to build up the necessary force to overcome stiction before initiating movement. Adding this inner loop with a first-order low-pass filter (\(f_{cutoff} = 10-50 Hz\)) significantly reduces the steady-state error and dampens oscillations caused by the friction discontinuity, improving tracking performance.

3. Impact of Structural Stiffness

The compliance of the installation structure and the load path is often the limiting factor in an EMA’s dynamic performance, dictating its structural resonance. I analyze the step response under different combinations of anchorage (\(K_{Z1}\)) and transmission (\(K_{Z2}\)) stiffness, applying a 10,000 N step load disturbance at 5 seconds.

| Case | \(K_{Z1}\) (N/m) | \(K_{Z2}\) (N/m) | Resonant Freq. (Hz) | Step Response (No Disturbance) | Response to 10kN Load Step |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1×10⁷ | 1×10⁷ | ~7.75 | Poorly damped oscillation | Severe, sustained oscillation |

| B | 5×10⁸ | 1×10⁷ | ~35.6 | Well-damped, fast settling | Small, quickly damped transient |

| C | 1×10⁹ | 1×10⁷ | ~50.2 | Very similar to Case B | Very similar to Case B |

| D | 1×10⁷ | 5×10⁸ | ~8.2 | Significant oscillation persists | Large oscillation persists |

| E | 1×10⁷ | 1×10⁹ | ~8.3 | Significant oscillation persists | Large oscillation persists |

The analysis yields critical insights:

- Minimum Stiffness Requirement: A combined low stiffness (Case A, ~10⁷ N/m) results in a low-frequency resonance (~7.75 Hz), causing unacceptable oscillation and poor disturbance rejection. The calculated frequency matches the mass-spring model: \(f_{res} = \frac{1}{2\pi}\sqrt{K_{eq}/m_{load}}\), where \(1/K_{eq} = 1/10^7 + 1/10^7\).

- Diminishing Returns: Increasing stiffness beyond approximately 5×10⁸ N/m (Cases B vs. C) provides negligible further improvement in dynamic response.

- Relative Importance: Comparing Case B (\(K_{Z1}\) high) with Case D/E (\(K_{Z2}\) high) is revealing. Improving the often-overlooked anchorage stiffness \(K_{Z1}\) has a dramatically more positive effect on system damping and stability than improving the transmission stiffness \(K_{Z2}\) by the same order of magnitude. This underscores the paramount importance of designing a rigid interface between the EMA housing and the primary airframe structure.

Dynamic Simulation and Model Validation

To validate the integrated nonlinear model, I simulate the EMA’s response to a realistic, time-varying position command representative of a flight control surface maneuver. The simulation includes the baseline parameters, moderate backlash (0.02 mm), the full friction model, and structural stiffness values of \(K_{Z1} = K_{Z2} = 5×10^8\) N/m.

The results demonstrate that the modeled EMA, centered on a robust planetary roller screw assembly, successfully tracks the demanding command profile. The position tracking error is analyzed over the 200-second simulation.

| Metric | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Absolute Tracking Error | 1.8 | mm |

| Peak Error as % of Full Stroke (Assume 150mm) | 1.2 | % |

| RMS Tracking Error | < 0.5 | mm |

The maximum error of 1.8 mm (1.2% relative error) occurs during the most aggressive transient phases and is attributable to the combined effects of backlash reversal, friction, and the bandwidth limitations imposed by the system’s inertia and control gains. This level of performance confirms the model’s validity and indicates that an EMA utilizing a high-performance planetary roller screw assembly can meet the dynamic requirements for many flight control applications, though its tracking precision under extreme transients may still lag behind that of a perfectly sealed, high-bandwidth hydraulic actuator. The advantages in weight, efficiency, and maintainability, however, are compelling.

Conclusion

This detailed analysis of an Electro-Mechanical Actuator based on a planetary roller screw assembly provides a framework for understanding and optimizing its dynamic performance. The key conclusions are:

- Nonlinearities are Dominant: The dynamic response and accuracy of the EMA are profoundly influenced by nonlinear factors. Mechanical backlash in the planetary roller screw assembly and gear train induces oscillations and limits control bandwidth, while friction causes steady-state errors and degrades low-speed performance.

- Structural Compliance is Critical: The stiffness of the mechanical path from the actuator housing to the load is a primary determinant of system stability. A combined anchorage and transmission stiffness on the order of 10⁸ N/m is necessary to push the structural resonance to a sufficiently high frequency (>30 Hz). Importantly, ensuring high anchorage stiffness (housing attachment) is more effective for improving overall damping and transient response than focusing solely on the transmission linkage stiffness.

- Model Fidelity: The developed multi-domain nonlinear model, incorporating these effects, accurately predicts system behavior. Validation against a dynamic command profile shows a peak tracking error of 1.2%, demonstrating the model’s utility as a design and analysis tool.

- Path to Performance: To realize the full potential of planetary roller screw assembly-based EMAs, design must focus on minimizing backlash through preload and precision manufacturing, mitigating friction with advanced materials and lubrication, and maximizing structural stiffness, particularly at the mounting interfaces. Control strategies must incorporate compensation for these inherent nonlinearities.

This work establishes a foundation for the continued development, optimization, and deployment of high-power-density EMAs in safety-critical applications where reliability, efficiency, and performance are paramount.