In my research, I focus on the advanced dynamics simulation of cycloidal drive systems, which are critical components in precision machinery such as industrial robots. The cycloidal drive, known for its high torque density, compact size, and excellent backlash performance, presents complex dynamic behaviors that require detailed investigation. Through this study, I aim to leverage modern computational tools to build and analyze virtual prototypes, thereby enhancing the design and reliability of cycloidal drive mechanisms. The integration of multi-body dynamics and finite element analysis allows for a comprehensive understanding of stress distributions, vibration characteristics, and overall system performance under operational conditions.

The cycloidal drive operates on the principle of cycloidal motion, where a cycloidal disk meshes with multiple pins to achieve high reduction ratios. This mechanism is often part of a broader 2K-V planetary transmission system, combining both external and internal gearings. My approach involves constructing detailed models using software like MSC ADAMS and ANSYS, performing simulations that range from rigid-body dynamics to flexible-body interactions. By doing so, I can predict real-world behaviors such as contact forces, stress concentrations, and dynamic responses, which are essential for optimizing the cycloidal drive for demanding applications.

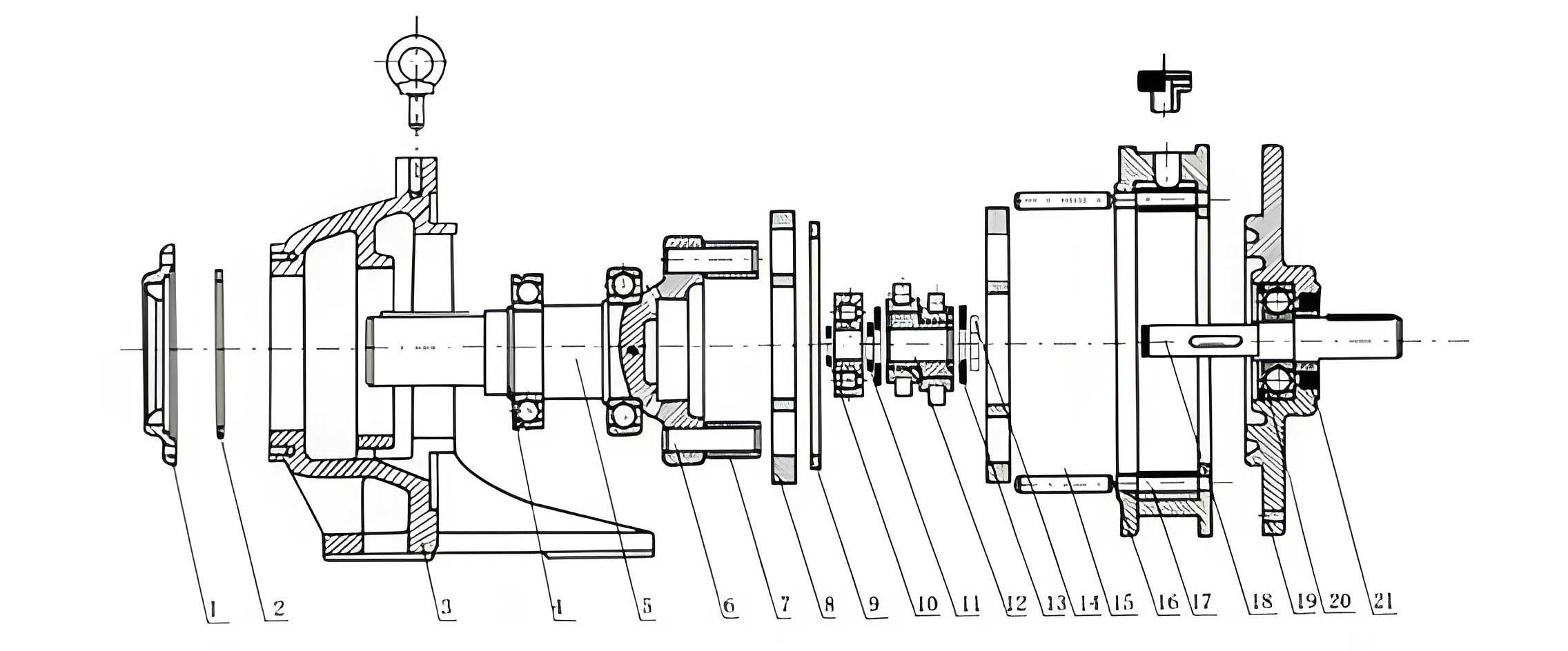

To begin, I developed a multi-rigid-body model of the cycloidal drive system. This model assumes all components as rigid bodies, neglecting elastic deformations for initial dynamics assessment. The modeling process started with 3D CAD software, where I created geometric representations of each part, including the cycloidal disk, pin gear, input shaft, and planetary carriers. These components were then imported into MSC ADAMS via an interface, where I applied constraints and contact forces to replicate the mechanical interactions. The contact between the cycloidal disk and pins is particularly crucial, as it governs the torque transmission and efficiency of the cycloidal drive.

The contact forces in the cycloidal drive were modeled using Hertzian contact theory, which relates the normal force \(P\) to the deformation \(\delta\) between two elastic bodies. The formula is given by:

$$ P = K \delta^{3/2} $$

where \(K\) is the contact stiffness coefficient, defined as:

$$ K = \frac{4}{3} R^{1/2} E^* $$

with \(R\) being the equivalent radius:

$$ \frac{1}{R} = \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} $$

and \(E^*\) as the effective Young’s modulus:

$$ \frac{1}{E^*} = \frac{1 – \nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \nu_2^2}{E_2} $$

Here, \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) are the radii of the cycloidal disk and pins at contact points, \(\nu_1\) and \(\nu_2\) are Poisson’s ratios, and \(E_1\) and \(E_2\) are Young’s moduli. In MSC ADAMS, this is implemented as a solid-to-solid contact force, which I applied to all meshing pairs in the cycloidal drive. The damping effects were minimized to focus on elastic interactions, ensuring accurate simulation of the cycloidal drive’s dynamics.

To validate the multi-rigid-body model, I performed transmission ratio tests. For a cycloidal drive with a fixed pin gear, the theoretical reduction ratio \(i\) can be calculated using kinematic transformation methods. In my simulations, I applied an input angular velocity and measured the output response under both no-load and rated-load conditions. The results confirmed that the virtual model accurately replicated the expected ratio, demonstrating the reliability of the cycloidal drive model. For instance, with an input speed of 4830°/s and a load torque of 231,000 N·mm, the output speed stabilized at 30°/s, matching the theoretical ratio of 161:1. This validation step is essential for ensuring that subsequent analyses on the cycloidal drive are based on a credible foundation.

Next, I analyzed the meshing forces between the cycloidal disk and pins. In a cycloidal drive, multiple pins engage with the cycloidal disk simultaneously, but the load distribution varies cyclically. I selected individual pins to monitor their force profiles over time. The results showed sinusoidal patterns, indicating periodic engagement and disengagement as the cycloidal disk rotates. This aligns with theoretical predictions for cycloidal drives, where the force distribution depends on the disk’s profile and pin positions. Understanding these forces is vital for designing cycloidal drives with improved durability and reduced wear.

| Material | Young’s Modulus (N/m²) | Poisson’s Ratio | Density (kg/m³) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCr15 Bearing Steel | 2.08 × 10¹¹ | 0.3 | 7.85 × 10³ |

| Structural Steel | 2.10 × 10¹¹ | 0.3 | 7.85 × 10³ |

Moving beyond rigid-body assumptions, I developed a flexible-body model to capture the elastic deformations of the cycloidal disk. This is critical because the cycloidal drive operates under high loads, and components like the cycloidal disk can experience significant bending and vibrational modes. Using ANSYS, I created a finite element model of the cycloidal disk, discretizing it with SOLID95 elements for accurate stress and modal analysis. The material properties, as listed in Table 1, were assigned to ensure realistic behavior. I then extracted modal information, including natural frequencies and mode shapes, to generate a Modal Neutral File (.mnf) for import into MSC ADAMS.

The modal analysis revealed the dynamic characteristics of the cycloidal disk. I computed the first 10 natural frequencies, which are essential for avoiding resonance in the cycloidal drive during operation. The frequencies ranged from low values for rigid-body modes to higher ones for elastic deformations. For example, the first elastic mode occurred at approximately 2962 Hz, corresponding to bending vibrations that could affect the meshing accuracy in the cycloidal drive. By incorporating these modes into the MSC ADAMS model, I built a rigid-flexible hybrid system where the cycloidal disk is treated as flexible, while other parts remain rigid for computational efficiency.

| Mode Number | Frequency (Hz) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1-6 | 0.0 | Rigid-body modes |

| 7 | 2961.98 | First bending mode |

| 8 | 3099.30 | Second bending mode |

| 9 | 4905.42 | Torsional mode |

| 10 | 6635.34 | Higher-order deformation |

In the rigid-flexible hybrid model, I connected the flexible cycloidal disk to the rigid bodies using constraint equations. To avoid issues with contact definition on flexible surfaces, I retained a lightweight rigid dummy part attached to the flexible disk, allowing for seamless force transmission in the cycloidal drive. This approach ensured that the system’s dynamics were preserved while enabling detailed stress analysis. I then conducted dynamic simulations under the same loading conditions as before, verifying that the transmission ratio remained consistent. This step confirmed that the flexible-body model of the cycloidal drive is valid for further in-depth studies.

One of the key aspects of this research is the dynamic stress analysis of the cycloidal disk. Using MSC ADAMS/Durability, I monitored the von Mises stress distribution on the cycloidal disk during operation. The results showed that stress concentrations occur at critical locations, such as the interfaces between扇形孔 and circular holes on the disk. These areas are prone to fatigue failure in cycloidal drives, especially under cyclic loading. The stress values fluctuated over time, with peak stresses reaching up to 0.02 MPa in my simulations. By animating the stress contours, I visualized how stress propagates through the cycloidal drive components, providing insights for design improvements.

To quantify the stress variations, I tracked specific nodes on the cycloidal disk. For instance, Node 5428, located at a high-stress region, exhibited periodic stress peaks corresponding to the engagement with pins. The stress-time curve followed a pattern similar to the meshing force profiles, highlighting the direct relationship between load and stress in the cycloidal drive. Similarly, Node 520 and Node 441 showed comparable trends, confirming that the cycloidal disk’s stress distribution is highly dynamic and influenced by the rotational position. This analysis underscores the importance of considering flexible-body effects in the design of cycloidal drives to ensure long-term reliability.

Furthermore, I explored the impact of various parameters on the cycloidal drive’s performance. For example, I varied the pin radius \(R_2\) and the Young’s modulus \(E\) to see how contact stresses and transmission efficiency change. The Hertzian contact model allowed me to derive sensitivity equations, such as:

$$ \frac{\partial P}{\partial R_2} = -\frac{2}{3} K \delta^{3/2} \frac{1}{R_2^2} $$

This indicates that increasing the pin radius reduces contact forces, which can mitigate wear in the cycloidal drive. Additionally, I investigated the effect of lubrication by adjusting damping coefficients in the contact model, though this was kept minimal in my primary simulations to focus on structural dynamics.

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Input Speed | 4830 | °/s |

| Load Torque | 231,000 | N·mm |

| Number of Pins | 40 | – |

| Cycloidal Disk Thickness | 20 | mm |

| Contact Stiffness Coefficient | 1.5 × 10⁵ | N/mm^(3/2) |

Another important consideration is the vibrational behavior of the cycloidal drive. From the modal analysis, I identified critical frequencies that could lead to resonance if excited by operational loads. For instance, the first bending mode at 2962 Hz might be excited by high-frequency torque fluctuations in the cycloidal drive. To prevent this, I recommend design modifications such as adding stiffening ribs or optimizing the disk’s geometry. The mode shapes, visualized through ANSYS, showed deformation patterns that align with stress concentration areas, reinforcing the need for integrated dynamics and stress analysis in cycloidal drive development.

In addition to stress and vibration, I evaluated the efficiency of the cycloidal drive. While efficiency is often high due to rolling contact, losses can occur from sliding friction and elastic hysteresis. Using the dynamic simulations, I computed power losses based on contact forces and velocities. The efficiency \(\eta\) can be expressed as:

$$ \eta = \frac{P_{\text{out}}}{P_{\text{in}}} = 1 – \frac{\sum F_i v_i}{T \omega} $$

where \(F_i\) and \(v_i\) are contact forces and sliding velocities at pin interfaces, \(T\) is input torque, and \(\omega\) is angular velocity. My results indicated that the cycloidal drive maintains efficiency above 90% under rated loads, but it drops slightly at higher speeds due to increased dynamic effects. This analysis helps in optimizing the cycloidal drive for energy-efficient applications.

To provide a comprehensive view, I compared the multi-rigid-body and flexible-body models. The rigid-body model offered faster simulations and was sufficient for kinematic validation, but it underestimated stresses and vibrations. In contrast, the flexible-body model, though computationally intensive, revealed detailed stress distributions and modal responses that are crucial for durability assessment of the cycloidal drive. This comparison emphasizes the value of using hybrid modeling techniques for complex systems like the cycloidal drive, where both global dynamics and local deformations matter.

Looking ahead, there are several avenues for further research on cycloidal drives. For instance, incorporating thermal effects could provide insights into heat generation and dissipation during operation. Additionally, experimental validation using physical prototypes would strengthen the simulation findings. I also plan to explore advanced materials, such as composites, for the cycloidal disk to reduce weight and enhance performance. The integration of machine learning for predictive maintenance in cycloidal drives is another promising area, leveraging the dynamic data from simulations.

In conclusion, my study demonstrates the effectiveness of dynamics simulation in analyzing cycloidal drive systems. Through multi-body and finite element approaches, I have captured key behaviors such as transmission accuracy, meshing forces, stress distributions, and vibrational modes. The cycloidal drive, with its unique kinematics, benefits greatly from these virtual prototyping techniques, enabling optimized designs for high-precision applications. The insights gained from this research can guide engineers in developing more reliable and efficient cycloidal drives, contributing to advancements in robotics and industrial automation.

To summarize the key equations used in this analysis of the cycloidal drive, I present the following:

- Hertzian contact force: $$ P = K \delta^{3/2} $$

- Contact stiffness: $$ K = \frac{4}{3} R^{1/2} E^* $$

- Effective modulus: $$ \frac{1}{E^*} = \frac{1 – \nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \nu_2^2}{E_2} $$

- Efficiency estimation: $$ \eta = 1 – \frac{\sum F_i v_i}{T \omega} $$

These formulas, along with the tabulated data, form the foundation for understanding and simulating the cycloidal drive. By repeatedly applying these principles, I ensured that the cycloidal drive model accurately reflects real-world dynamics, paving the way for future innovations in this field.