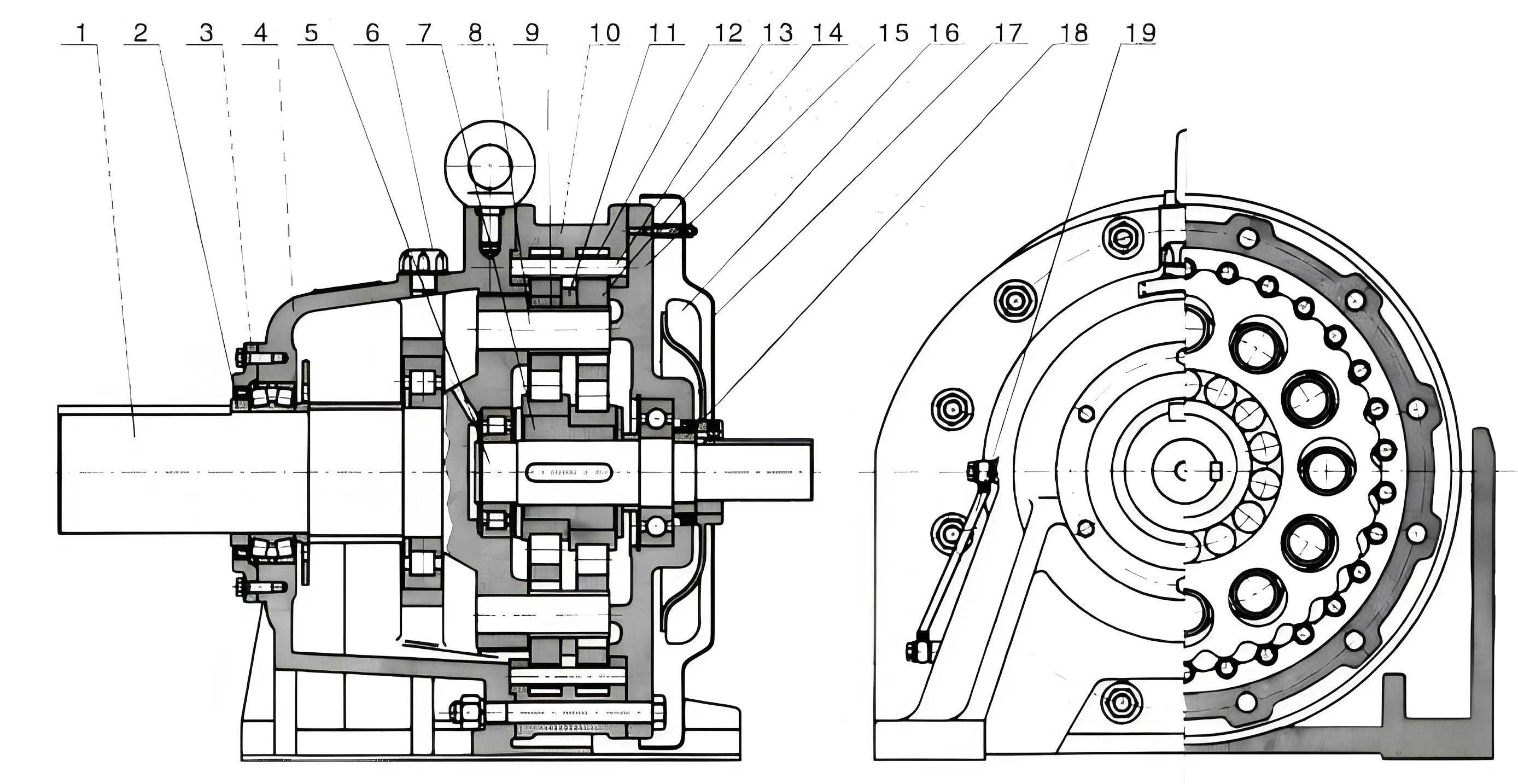

In my years of maintaining heavy machinery, particularly tower cranes, I have faced numerous challenges, but few were as critical as the sudden failure of a cycloidal drive. The cycloidal drive, a key component in the slewing mechanism, ensures smooth and precise rotation of the crane’s tower. This gear system, known for its high reduction ratio and compact design, is essential for operational efficiency. One incident involved a Q1 T6 type tower crane that had been in service for nearly a decade. During a routine construction operation, the tower suddenly lost its ability to slew. Initial diagnostics pointed to the gearbox, and upon disassembly, we discovered severe damage to the secondary stage of the cycloidal drive. This experience led me to delve deep into the repair methodologies for such precision components, especially when replacement parts are unavailable. The cycloidal drive’s unique geometry and material composition make its restoration a complex task, requiring meticulous planning and execution.

The failure manifested as multiple cracks, wear spots, and fragmented sections on the cycloidal disc of the drive. This component, typically made from high-carbon chromium bearing steel like GCr15, is subjected to significant cyclic stresses. The cracks varied in depth and length, some superficial and others penetrating entirely through the disc. Understanding the root cause is crucial for effective repair. In cycloidal drives, stress concentration at the lobe roots, combined with material fatigue from years of service, often initiates such failures. The following table summarizes common failure modes observed in cycloidal drives:

| Failure Mode | Description | Potential Cause in Cycloidal Drive |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Cracks | Hairline fractures on the disc surface | Cyclic bending stress, material defects |

| Deep Penetrating Cracks | Cracks extending through the disc thickness | Overload, shock loading, stress corrosion |

| Wear and Pitting | Loss of material on lobe flanks and pins | Inadequate lubrication, abrasive contamination |

| Fragmentation/Chipping | Breaking off of lobe sections | Impact loads, brittle fracture due to high hardness |

The material, GCr15, presents significant challenges for repair due to its high carbon content (approximately 1.0%) and chromium alloying. This composition gives the cycloidal drive its necessary hardness and wear resistance but also makes it prone to welding-related issues. The weldability can be assessed through its carbon equivalent (CE), often calculated using formulas like the International Institute of Welding (IIW) formula:

$$ CE = C + \frac{Mn}{6} + \frac{Cr + Mo + V}{5} + \frac{Ni + Cu}{15} $$

For GCr15, with typical compositions, the CE often exceeds 0.6, indicating poor weldability with high risks of cold cracking and hardening. The heat-affected zone (HAZ) is susceptible to martensite formation, leading to brittleness. Therefore, any repair strategy for a cycloidal drive must account for these metallurgical constraints.

Upon disassembly and inspection, we mapped all defects on the cycloidal disc. The first step was crack removal. Using a grinder, we eliminated all crack traces, starting from the crack tips to prevent propagation. For non-penetrating cracks, we ground a groove with a smooth, radiused base to reduce stress concentration. The groove profile can be described geometrically. If the crack depth is \( d \) and the required groove width at the surface is \( w \), the cross-sectional area \( A \) to be removed for a U-groove is approximately:

$$ A = \frac{1}{2} \pi \left(\frac{w}{2}\right)^2 \quad \text{for a semicircular base} $$

For penetrating cracks, a single-V groove was prepared with an angle \( \theta \) typically between 60° to 90°. The depth \( D \) equals the material thickness. Proper groove geometry is critical to ensure full penetration during welding and minimize residual stresses in the cycloidal drive component.

Before welding, we assessed the weldability of the cycloidal drive material. GCr15 has high hardenability, meaning it rapidly forms martensite upon cooling, leading to cracks. Sulfur and phosphorus segregation can promote hot cracking. To mitigate this, we implemented several measures. First, preheating was considered but ultimately not used due to control requirements; instead, we relied on low heat input and specific filler material. The choice of filler metal is paramount. We selected an A307 (E309) stainless steel electrode. This austenitic filler provides good crack resistance due to its ability to dissolve carbon and tolerate dilution, and it offers reasonable machinability post-weld. The electrodes were baked at 350°C for 2 hours to remove moisture, reducing hydrogen-induced cracking risk.

The welding sequence was strategic: we first addressed short, shallow cracks, then penetrating cracks, and finally built up worn or missing sections. For short cracks, welding commenced at the crack tail, moving forward in a stitch welding technique—depositing small beads while continuously monitoring for new crack initiation. This stepwise approach allowed us to verify the procedure’s suitability. For penetrating cracks, after welding one side, the root was back-gouged thoroughly to sound metal before completing the weld. Worn areas were cleaned of oil and rust prior to deposition.

The welding parameters were tightly controlled to manage heat input. Heat input \( Q \) per unit length is given by:

$$ Q = \frac{60 \cdot V \cdot I}{1000 \cdot S} $$

where \( V \) is voltage in volts, \( I \) is current in amperes, and \( S \) is travel speed in mm/min. For our process, using an AX-320 DC power source on reverse polarity (electrode positive), we maintained:

| Parameter | Value | Role in Cycloidal Drive Repair |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Type | A307 (E309), Ø3.2 mm | Austenitic stainless steel for crack resistance and ductility |

| Current (I) | 90–100 A | Balances penetration and heat input |

| Voltage (V) | 20–22 V | Stable arc for controlled deposition |

| Travel Speed (S) | Approx. 90–120 mm/min | Calculated to achieve 8–12 kJ/cm heat input |

| Heat Input (Q) | 8–12 kJ/cm | Minimizes HAZ hardening and distortion |

Post-weld, the entire cycloidal disc was allowed to cool slowly under insulation to reduce thermal gradients and stress. Upon reaching ambient temperature, it was machined on a lathe to restore the two planar surfaces. Excess weld metal at the edges was hand-filed to match the original cycloidal profile. The accuracy of the lobe geometry is vital for the proper meshing with needle rollers in the cycloidal drive. The profile of a cycloidal disc is defined by parametric equations based on epitrochoidal generation. For a cycloidal drive with pin circle radius \( R_p \), eccentricity \( e \), and number of lobes \( N \), the coordinates of a lobe can be expressed as:

$$ x = (R_p – e) \cos(\phi) + e \cos\left(\frac{R_p – e}{e} \phi\right) $$

$$ y = (R_p – e) \sin(\phi) – e \sin\left(\frac{R_p – e}{e} \phi\right) $$

where \( \phi \) is the input angle. Restoration required careful measurement to ensure these geometrical constraints were met, preserving the reduction ratio and smooth operation of the cycloidal drive.

The repaired cycloidal drive was reinstalled and has been operating successfully for over five years without issue. This outcome underscores the viability of weld repair for high-value components like cycloidal drives when done with precision. However, this experience prompted me to explore broader aspects of cycloidal drive maintenance. Cycloidal drives, also known as cycloidal speed reducers, are widely used not only in tower cranes but also in robotics, conveyor systems, and industrial machinery due to their high torque density and zero-backlash characteristics. The design involves a cycloidal disc orbiting inside a ring of stationary pins, creating a high reduction ratio through eccentric motion. The transmission ratio \( i \) for a single-stage cycloidal drive is given by:

$$ i = \frac{N_p}{N_p – N_l} $$

where \( N_p \) is the number of pins and \( N_l \) is the number of lobes on the disc. Typically, \( N_p = N_l + 1 \), yielding a high ratio. This compact design, however, concentrates stress on the lobes, making them failure-prone.

Beyond welding, other repair techniques for cycloidal drives include metal stitching, thermal spraying, and replacement of individual components. Preventive maintenance is key. Regular oil analysis can detect wear particles from the cycloidal drive. Vibration monitoring can identify imbalance or misalignment. Lubrication must use high-pressure additives to withstand the Hertzian contact stresses between lobes and pins. The contact stress \( \sigma_c \) between a cylindrical pin and a cycloidal lobe can be approximated by Hertzian theory:

$$ \sigma_c = \sqrt{\frac{F}{\pi L} \cdot \frac{\frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2}}{\frac{1-\nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1-\nu_2^2}{E_2}}} $$

where \( F \) is the normal force, \( L \) is the contact length, \( R_1, R_2 \) are radii of curvature, \( E \) is Young’s modulus, and \( \nu \) is Poisson’s ratio. Proper lubrication reduces this stress, extending the cycloidal drive’s life.

In another case involving mobile cranes, similar principles apply. For instance, hydraulic cylinder retraction issues in boom mechanisms often stem from internal leakage or valve failures, analogous to how cycloidal drive failures originate from material fatigue. The diagnostic approach—isolating components and observing fluid flow—mirrors the systematic troubleshooting we employed for the cycloidal drive. This cross-equipment perspective reinforces that understanding root causes and applying controlled repair techniques are universal in heavy machinery maintenance.

To further elaborate on welding metallurgy for cycloidal drives, the microstructure evolution in the HAZ can be modeled using continuous cooling transformation (CCT) diagrams. For GCr15, rapid cooling promotes martensite, which is hard but brittle. The use of austenitic filler metal like A307 helps because it retains austenite at room temperature, absorbing carbon and reducing hardness gradients. The dilution ratio \( D \) between base metal and filler affects the weld metal composition:

$$ D = \frac{A_{bm}}{A_{bm} + A_{fm}} $$

where \( A_{bm} \) and \( A_{fm} \) are the cross-sectional areas melted from base and filler metals, respectively. Controlling \( D \) through groove design and welding technique minimizes the formation of hard phases in the cycloidal drive repair zone.

Additionally, residual stresses from welding can affect the fatigue performance of the cycloidal drive. These stresses can be estimated using formulas for thermal stress in a semi-infinite plate subjected to a localized heat source. For a point heat source of power \( q \) moving at speed \( v \), the temperature field \( T(x,y,z,t) \) can be derived from the heat conduction equation:

$$ \nabla^2 T – \frac{1}{\alpha} \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = -\frac{q}{\kappa} \delta(x-vt)\delta(y)\delta(z) $$

where \( \alpha \) is thermal diffusivity and \( \kappa \) is thermal conductivity. The resulting stress \( \sigma_{xx} \) due to constraint is proportional to \( E \alpha \Delta T \), where \( \Delta T \) is the temperature change. Post-weld heat treatment (PWHT) is sometimes used to relieve these stresses, but for precision components like cycloidal drives, machining after welding often suffices if distortion is controlled.

The economic impact of repairing a cycloidal drive versus replacement is substantial. A new cycloidal drive unit can cost tens of thousands, while repair costs are a fraction, provided the core geometry is restorable. This makes weld repair a valuable skill for maintenance teams. In our case, the savings were significant, and the crane returned to service with minimal downtime. The cycloidal drive’s performance post-repair was monitored through periodic inspections, checking for abnormal noise or vibration, which are early indicators of issues in cycloidal drives.

Looking forward, advancements in additive manufacturing could revolutionize cycloidal drive repair. Techniques like directed energy deposition (DED) could rebuild lobe profiles with precise material control. However, traditional arc welding remains a practical and effective method for field repairs. The key is a thorough understanding of the cycloidal drive’s function, material behavior, and welding dynamics. Every cycloidal drive repair project reinforces the importance of preparation, from defect mapping to parameter optimization.

In conclusion, the successful restoration of a cycloidal drive in a tower crane exemplifies how detailed technical knowledge and careful execution can extend the life of critical machinery. The cycloidal drive, with its complex geometry and demanding material, requires a methodical approach to repair. By addressing weldability challenges, controlling heat input, and ensuring geometrical accuracy, we achieved a durable repair that has proven reliable over years of service. This experience has deepened my appreciation for the cycloidal drive’s role in industrial equipment and the value of sustainable maintenance practices. As technology evolves, the principles of precision and adaptability remain central to maintaining these essential components, ensuring that cycloidal drives continue to operate efficiently in demanding applications.