In the pursuit of advanced mechanical systems, two critical domains often dictate overall performance and reliability: the science of dynamic sealing in high-pressure environments and the precision of power transmission through specialized gearing. My analysis today converges on these domains, drawing insights from rigorous research on Stirling engine piston rod seals and linking these principles to a significant parallel development—the maturation of domestically produced precision cycloidal drive units. This exploration is not merely academic; it represents a practical framework for optimizing complex mechanical assemblies where friction, wear, and efficient force transmission are paramount.

The foundational challenge in high-performance engines like the Stirling engine lies in the piston rod’s dynamic seal. This interface must contain high-pressure gases while accommodating reciprocating motion, a scenario where sealing performance and component wear are in constant opposition. From the experimental data, a clear, non-linear relationship emerges. In the initial 20-hour period, an increase in sealing cavity pressure correlates with a decrease in gas leakage. This can be intuitively understood through a basic contact mechanics principle: the applied pressure enhances the conformity of the sealing ring to its mating surface, improving the seal’s integrity. One can model the nominal contact stress $\sigma_n$ at the interface simplistically as a function of the applied pressure $P$ and the seal’s geometric stiffness $k$:

$$ \sigma_n \approx k \cdot P $$

Higher $\sigma_n$ initially leads to better sealing. However, the long-term narrative is governed by tribology. Beyond the 20-hour mark, the trend reverses for higher pressures. The sustained high contact stress accelerates abrasive wear, degrading the seal’s geometry and thus increasing leakage. This highlights the critical trade-off: maximizing sealing performance can inadvertently accelerate its own failure mechanism through excessive wear.

To navigate this trade-off systematically, one cannot rely solely on physical testing, which is costly and time-consuming. Here, the construction of high-fidelity surrogate models becomes indispensable. The research I am analyzing employed Kriging models, a powerful spatial interpolation technique, to approximate the complex functional relationships between the sealing cavity pressure (the design variable) and the two conflicting objectives: wear mass $W(P)$ and leakage $L(P)$. The Kriging model predicts the response $\hat{y}$ at a new point $\mathbf{x}$ as a combination of a global polynomial trend and a localized deviation:

$$ \hat{y}(\mathbf{x}) = \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j f_j(\mathbf{x}) + Z(\mathbf{x}) $$

where $f_j$ are basis functions, $\beta_j$ are coefficients, and $Z(\mathbf{x})$ is a Gaussian stochastic process with zero mean and a covariance defined by a kernel function, often of the form:

$$ \text{Cov}(Z(\mathbf{x}^i), Z(\mathbf{x}^j)) = \sigma^2 \exp\left(-\sum_{k=1}^{d} \theta_k |x_k^i – x_k^j|^{2}\right) $$

These models, built from a limited set of high-fidelity simulation or experimental data points, allow for the rapid evaluation of thousands of design configurations. With accurate Kriging models for wear and leakage established, the problem is framed as a formal multi-objective optimization (MOO):

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \underset{P}{\text{minimize}}

& & \mathbf{F}(P) = [W(P), \; L(P)]^T \\

& \text{subject to}

& & P_{\text{min}} \leq P \leq P_{\text{max}}

\end{aligned}

$$

To solve this MOO problem, the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) was deployed. NSGA-II is exceptionally suited for such problems as it finds a set of Pareto-optimal solutions—solutions where one objective cannot be improved without worsening the other. The algorithm’s process of selection, crossover, mutation, and elitist non-dominated sorting efficiently explores the design space. The optimization converged on a specific pressure value, 6.95 MPa, as the optimal compromise. Subsequent experimental validation confirmed its superiority, showing stable, low leakage over extended durations with minimal wear, thereby proving the model’s predictive capability and the optimization’s effectiveness.

| Pressure Regime | Primary Mechanism | Leakage Trend | Wear Trend | Overall Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low to Moderate | Improved contact conformity | Decreasing | Moderate, linear | Sealing improves |

| High (Sustained) | Abrasive wear acceleration | Increasing after threshold | High, non-linear | Sealing degrades |

| Optimal (e.g., 6.95 MPa) | Balanced contact stress | Stable and minimal | Minimized | Long-term stability |

The methodologies demonstrated here—surrogate modeling (Kriging) and evolutionary multi-objective optimization (NSGA-II)—form a robust template for engineering design. It is a template that finds profound resonance in the adjacent field of precision gearing, particularly for robotic joints. The core challenges are analogous: managing contact stresses, minimizing wear, and maximizing efficiency in a compact, reliable package. This brings me directly to the groundbreaking advancement in domestic manufacturing: the precision cycloidal drive.

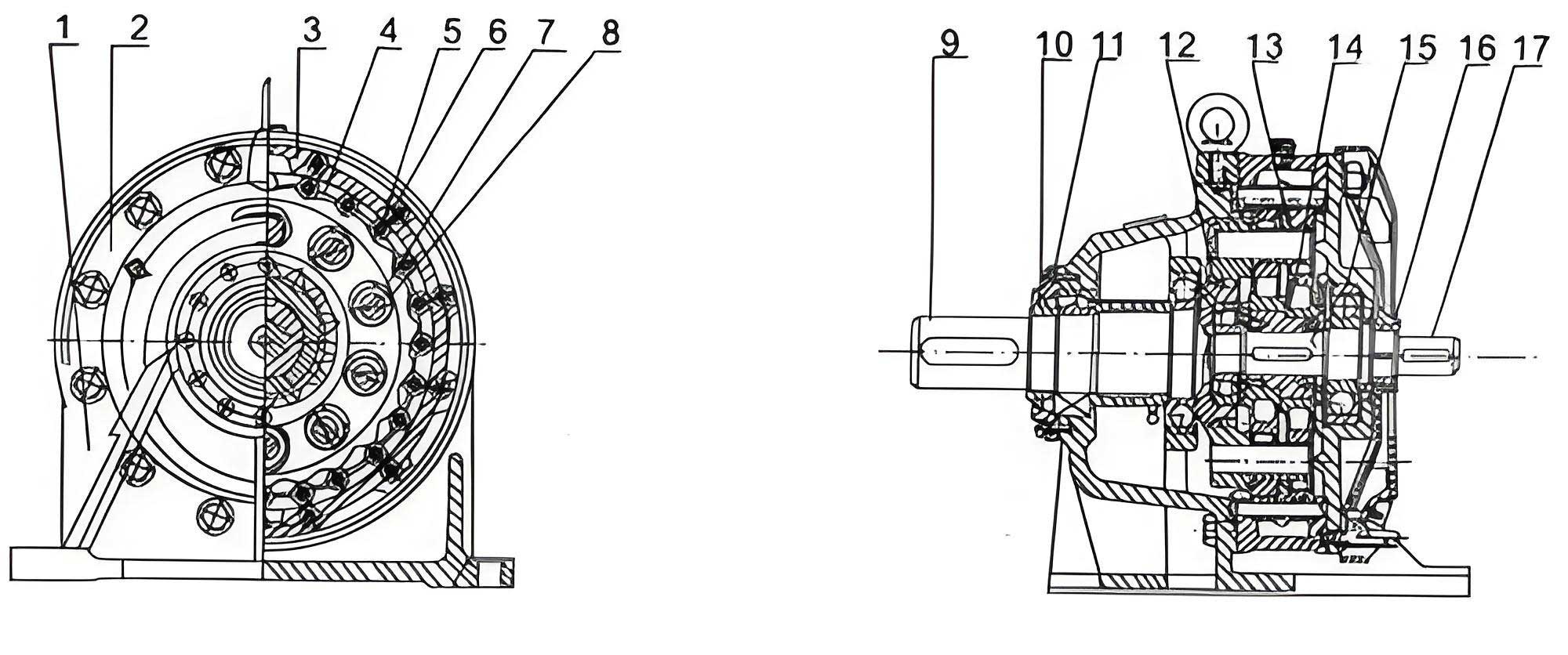

A cycloidal drive, or cycloidal speed reducer, operates on a fundamentally different principle than conventional planetary or harmonic drives. It uses an eccentric input to drive a cycloidal disk, which meshes with stationary pin gears in a lobing motion, achieving very high reduction ratios in a single stage. The advantages are significant: high torque density, exceptional shock load capacity, and potentially higher rigidity and longevity. However, its design and manufacturing have been notoriously complex, leading to historical dominance by a few international manufacturers.

The recent successful development and imminent production of a fully independent, domestically engineered precision cycloidal drive is a watershed moment. This achievement directly mirrors the optimization philosophy applied to the seal. The development team did not merely replicate existing designs; they engaged in a system-level optimization. Reports indicate they synthesized the advantages of RV and harmonic drives, directly addressing key limitations. Crucially, they solved the challenge of miniaturizing the cycloidal drive mechanism—a problem analogous to finding the optimal pressure point in the seal, balancing size (or stress) against performance.

| Feature / Technology | Harmonic Drive | RV Reducer (Conventional) | Advanced Domestic Cycloidal Drive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Principle | Elastic deformation of flexspline | Planetary + Cycloidal stage | Optimized single-stage cycloidal lobing |

| Key Strength | High precision, compactness | High rigidity, high torque | High torque & rigidity, compact size |

| Key Limitation | Limited lifetime, lower shock load capacity | Complex, difficult to miniaturize | Historical complexity in manufacturing |

| Structural Complexity | Moderate | High | Simplified, integrated design |

| Sealing & Contamination | Can be challenging | Standard | Fully sealed, prevents internal contamination |

The mathematical modeling behind an optimal cycloidal drive is deeply intricate, involving precise cycloidal tooth profile generation. The shape of the cycloidal disk tooth is defined by the parametric equations derived from the epicycloid or hypocycloid curve, modified for conjugate action with the pins. The basic epicycloid for a generating circle of radius $r_g$ rolling on a base circle of radius $R_b$ is:

$$ x = (R_b + r_g) \cos(\theta) – r_g \cos\left(\frac{R_b + r_g}{r_g} \theta\right) $$

$$ y = (R_b + r_g) \sin(\theta) – r_g \sin\left(\frac{R_b + r_g}{r_g} \theta\right) $$

Where $\theta$ is the rotation angle of the generating circle. For a cycloidal drive, this profile is then offset and modified to ensure multiple teeth are in contact for load distribution, a process requiring sophisticated optimization to balance stress concentration, backlash, and efficiency—a multi-objective problem akin to the seal optimization, likely solvable via similar metaheuristic or surrogate-model-based approaches.

The implications of this domestic breakthrough are substantial for industries like industrial robotics. As the world’s largest market for industrial robots for several consecutive years, reliance on imported core components like precision reducers has been a major cost and supply chain bottleneck. A high-performance, locally produced cycloidal drive directly addresses this, promising to significantly reduce the cost of robotic arms while enhancing their performance specifications. The reported “fully sealed” design is a critical feature, preventing internal lubricant leakage and external contaminant ingress—a sealing challenge directly parallel to the one in the Stirling engine, now solved at the gearbox level.

| System Component | Design Variable (Example) | Conflicting Objectives | Surrogate Model Technique | Optimization Algorithm | Optimal Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piston Rod Seal | Sealing Cavity Pressure (P) | Minimize Leakage vs. Minimize Wear | Kriging Model | NSGA-II | Balanced Pressure (6.95 MPa) |

| Cycloidal Drive Profile | Tooth Profile Parameters, Pin Diameter, Eccentricity | Maximize Torque Density vs. Minimize Stress Concentration vs. Minimize Backlash | Kriging / Polynomial Chaos | NSGA-II, MOEA/D | Optimal Tooth Geometry & Drive Configuration |

| System Integration | Material Pairings, Lubricant Type | Maximize Efficiency vs. Maximize Lifespan vs. Minimize Cost | Combined DoE & ML Models | Bayesian Optimization | Optimal System-Level Specification |

Let us synthesize these threads. The sealing study provides a clear, quantifiable demonstration of a systems engineering approach: define metrics, build predictive models, and formally optimize for the best compromise. The success of the domestic cycloidal drive represents the application of this very philosophy on a different, but structurally similar, problem. It is an optimization of geometry, materials, and assembly to achieve a Pareto-optimal solution in the multi-dimensional space of size, weight, torque, precision, durability, and cost.

Looking forward, the convergence of these advanced design methodologies with new manufacturing capabilities like high-precision machining and additive manufacturing opens vast possibilities. Future cycloidal drive iterations could feature topology-optimized housings for weight reduction, or integrated sensor cavities for condition monitoring. The sealing principles analyzed earlier could be further enhanced by applying similar modeling to the selection of composite seal materials or surface texture patterns, potentially using machine learning models trained on vast tribological datasets.

Furthermore, the integration of an optimized cycloidal drive into a system like a robotic actuator creates a new, higher-level optimization problem. The dynamic performance of the robot joint—its stiffness, resonant frequency, and thermal behavior—becomes a function of the reducer’s characteristics, the motor’s parameters, and the control algorithms. The next frontier lies in this co-design optimization, where the mechanical design (seals, gears, structures) and the control logic are optimized simultaneously, perhaps using multi-fidelity models where a high-fidelity FEA model of the cycloidal drive contact informs a lower-fidelity dynamic model of the entire robotic arm.

In conclusion, the meticulous work on Stirling engine seals is far more than an isolated case study. It is a testament to a modern, computationally-driven design paradigm that is essential for overcoming inherent engineering trade-offs. The parallel success in developing a world-class precision cycloidal drive validates this paradigm’s power in tangible, industry-shifting ways. Both narratives underscore that the future of high-performance mechanical systems lies not in incremental adjustments, but in the holistic, model-based, and intelligently optimized integration of all interacting components—from the microscopic seal interface to the macroscopic gear topology—enabling breakthroughs in efficiency, reliability, and autonomy.