As an engineer deeply involved in the field of precision power transmission, I have consistently observed the pivotal role played by the cycloidal drive. This mechanism, renowned for its high reduction ratios, compactness, and excellent torque-to-weight ratio, is a cornerstone in applications ranging from industrial robotics and medical equipment to aerospace actuators and manufacturing machinery. The core value proposition of the cycloidal drive lies in its ability to provide significant speed reduction and torque multiplication within a remarkably small envelope. However, its widespread adoption is sometimes tempered by limitations in its ultimate load capacity and longevity under extreme conditions. The primary objective of this extensive analysis is to delve into the structural mechanics of the cycloidal drive, identify the critical factors that constrain its load-bearing potential, and propose a detailed, analytically-backed design improvement centered on a novel load-sharing mechanism. Our focus will be on moving beyond mere imitation of existing designs and towards a fundamental understanding that enables performance breakthroughs.

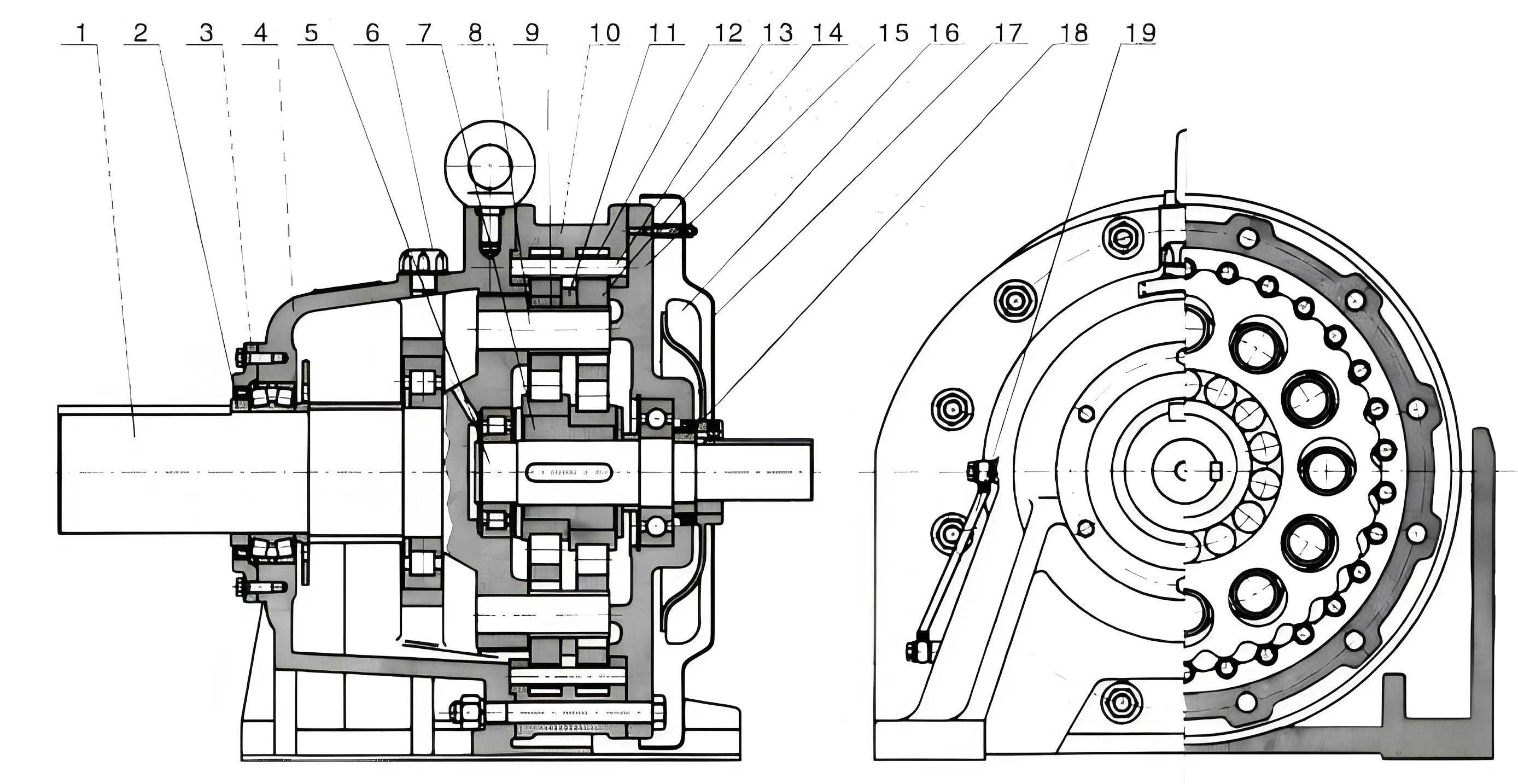

The operational principle of a standard cycloidal drive is elegant yet involves complex kinematics. It primarily consists of an input eccentric cam, a set of cycloidal disks (often called lobed wheels or simply cycloids), a stationary ring of pins (the “pinwheel” or “ring gear”), and an output mechanism, typically a set of pins and holes (a W-output or cycloidal disk bearing). As the high-speed input shaft rotates the eccentric, it imparts a compound wobbling motion to the cycloidal disks. These disks mesh with the fixed ring pins, causing their lobes to roll around the pin circle. This rolling motion is translated into a slow, high-torque rotation of the output shaft through the phase-shifted holes in the disks engaging with the output pins. The multi-lobe design ensures that several teeth are in contact simultaneously, theoretically distributing the load. However, practical limitations in manufacturing precision, assembly, and structural deflection often lead to uneven load distribution among these contact points, creating stress concentrations that become the Achilles’ heel of the drive’s capacity.

To lay a foundation for improvement, a critical examination of common failure modes and structural weaknesses in conventional cycloidal drive designs is essential. The performance ceiling is not defined by a single component but by a chain of interdependent elements.

Structural Analysis of Critical Components:

1. Housing and Frame Alignment: The housing, or机座, provides the foundational geometry for the entire cycloidal drive. Any misalignment here propagates throughout the assembly. The coaxiality tolerance between the bearing bores and the locating shoulder for the pin ring housing is critically stringent. Based on international standards, this coaxiality should typically be better than IT8 grade. A deviation $\Delta C$ from perfect coaxiality introduces a parasitic moment $M_{mis}$ even under a purely axial load $F$, effectively reducing the usable load capacity. This can be approximated as:

$$ M_{mis} = F \cdot \Delta C $$

This moment exacerbates uneven loading on the output bearings and the cycloidal disks themselves.

2. Pin Ring (Needle Gear) Integrity: The pin ring, or针齿壳, is a high-precision component. Its tolerances directly govern backlash and load distribution. Key parameters include:

– Pin circle diameter tolerance: Often held to j7 or tighter.

– Perpendicularity of pin hole axes to the mating flange face: Should exceed IT6 grade.

– Radial runout of the pin circle relative to the central bore: Must be minimized, often to levels equivalent to better than IT5.

– Cumulative pitch error between pin holes: This error $\Delta p_{\Sigma}$ is perhaps the most critical manufacturing metric. It prevents all cycloidal disk lobes from contacting their respective pins simultaneously with equal force. If the nominal force per contact is $F_{nom}$, the force on the $i$-th pin due to pitch error $\Delta p_i$ can be modeled as proportional to the displacement error, assuming a linear contact stiffness $k_c$:

$$ F_i = k_c \cdot (\Delta p_i + \delta_i) $$

where $\delta_i$ is the systemic deflection.

3. Output Mechanism and Bearing Configuration: The traditional W-output with cylindrical pins in oblong holes, while simple, creates a statically indeterminate system. The pins act as cantilever beams fixed at the output flange and loaded by the cycloidal disk holes. The deflection $\delta_{pin}$ at the load point for a pin of length $L$, diameter $d$, and elastic modulus $E$, under a force $F$ is given by:

$$ \delta_{pin} = \frac{F L^3}{3 E I} $$

where $I = \frac{\pi d^4}{64}$. Under high torque, the pins in the direction of the resultant force (near the $90^\circ$ and $270^\circ$ positions relative to the load vector) deflect significantly more than those near $0^\circ$ and $180^\circ$. This elastic mismatch is a primary source of uneven load sharing, leading to premature wear or fracture of the most heavily loaded pins and the corresponding lobes on the cycloidal disk. The following table summarizes the key limitations and their consequences:

| Component | Primary Limitation | Consequence for Load Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Housing | Coaxiality and parallelism errors | Induced bending moments, bearing overload |

| Pin Ring | Cumulative pitch error, runout | Uneven meshing, stress concentration on specific lobes |

| Output Pins | Cantilever bending, lack of forced coordination | Severely non-uniform load distribution, pin failure |

| Cycloidal Disk | Stress concentration at lobe root, heat treatment limits | Fatigue crack initiation and propagation |

The central thesis for enhancing the cycloidal drive is to address the most flexible link in this chain: the output pin load distribution. A passive, integrated load-sharing (or “force-equalizing”) ring presents an elegant and manufacturable solution.

Design and Analysis of the Integrated Load-Sharing Ring Mechanism

The proposed modification involves integrating a secondary ring, the Load-Sharing Ring (LSR), onto the output stage. This ring is mounted to the output shaft but is allowed a limited degree of compliant movement relative to it, specifically in the plane of the output pins. It features a set of precision holes that engage with a secondary shoulder or groove machined onto each output pin, located outboard of the primary cycloidal disk engagement zone. Crucially, the fit between the LSR holes and the pin shoulders is a precise sliding fit, not a tight interference. The primary function of the LSR is to kinematically couple all output pins together, forcing them to conform to a more uniform displacement field.

Mechanical Model and Deformation Coordination: Under an output torque $T_{out}$, the cycloidal disks exert a set of forces $\vec{F_i}$ on the output pins at the engagement points. In the traditional design, each pin deflects independently. With the LSR, the outer ends of all pins are constrained to follow the displacement of the LSR. We model the LSR as having three primary degrees of freedom relative to the nominal output shaft center: two translational ($\Delta x$, $\Delta y$) and one rotational ($\Delta \alpha$).

Consider the $i$-th output pin located at an angular position $\theta_i$ on the pitch circle of radius $R_w$. Its primary deflection at the cycloidal disk engagement point due to pin bending and shear is $\vec{\delta_{c,i}} = (\delta_{cx,i}, \delta_{cy,i})$. The deflection at the LSR engagement point, $\vec{\delta_{L,i}}$, is constrained by the motion of the LSR. The compatibility condition enforced by the rigid LSR geometry is:

$$ \vec{\delta_{L,i}} = \begin{pmatrix} \Delta x \\ \Delta y \end{pmatrix} + \Delta \alpha \begin{pmatrix} -R_w \sin\theta_i \\ R_w \cos\theta_i \end{pmatrix} $$

This equation provides two scalar equations per pin. The force $\vec{F_{L,i}}$ exerted by the LSR on the pin at this point is related to the difference between the free deflection of the pin’s end and the LSR’s imposed position, acting through the stiffness of the pin in this secondary mode. This creates a system of equations linking all pin forces.

Force Equilibrium and Torque Transmission: The total output torque is the sum of contributions from all $N$ pins:

$$ T_{out} = \sum_{i=1}^{N} \left( \vec{r_i} \times \vec{F_{c,i}} \right)_z $$

where $\vec{r_i}$ is the position vector of the $i$-th pin’s primary engagement point, and $\vec{F_{c,i}}$ is the force from the cycloidal disk on that pin. The forces $\vec{F_{c,i}}$ and $\vec{F_{L,i}}$ on each pin must satisfy static equilibrium for the pin as a free body. The LSR itself must be in force and moment equilibrium:

$$ \sum_{i=1}^{N} \vec{F_{L,i}} = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad \sum_{i=1}^{N} \left( \vec{r_{L,i}} \times \vec{F_{L,i}} \right)_z = 0 $$

where $\vec{r_{L,i}}$ is the position vector to the LSR engagement point on the $i$-th pin.

By solving this coupled system—comprising pin equilibrium equations, LSR equilibrium equations, and the kinematic compatibility equations—for the unknown forces $\vec{F_{c,i}}$ and LSR displacements ($\Delta x, \Delta y, \Delta \alpha$), we obtain the load distribution. The solution consistently shows that the LSR mechanism actively redistributes load. Pins that would be heavily loaded in the traditional design (near $\theta = 90^\circ$) have part of their load “shared” via the LSR with pins that were lightly loaded (near $\theta = 0^\circ$ and $180^\circ$). The following table contrasts the key characteristics of the traditional and LSR-enhanced designs:

| Aspect | Traditional Cycloidal Drive Output | LSR-Enhanced Cycloidal Drive Output |

|---|---|---|

| Load Distribution | Highly uneven. Ratio of max to min pin force can exceed 5:1 or more under load. | Significantly more even. Ratio of max to min pin force approaches 2:1 or better. |

| Structural Model | Statically indeterminate, pins as independent cantilevers. | Fully coupled system; pins as beams with coordinated end conditions. |

| Primary Failure Mode | Fatigue fracture of the 1-2 most loaded pins and corresponding disk lobes. | More generalized wear across all contact surfaces; higher overall load to initiate failure. |

| Stiffness | Non-linear, decreases with increasing load due to localized yielding. | More linear and higher overall torsional stiffness. |

| Manufacturing Complexity | Lower (simpler output flange). | Higher (requires precision LSR and modified pins). |

Quantitative Performance Enhancement: The improvement in load capacity can be quantified. Let $F_{max}^{trad}$ be the maximum force on any pin in the traditional design at the rated torque $T_{rated}$. The design is limited by material yield or fatigue strength at this point: $F_{max}^{trad} \approx S_{allowable} \cdot A$, where $S_{allowable}$ is the allowable stress and $A$ a geometric factor. In the LSR design, for the same output torque, the maximum force $F_{max}^{LSR}$ is lower. Therefore, the torque can be increased until $F_{max}^{LSR}$ reaches the same $S_{allowable} \cdot A$ limit. The potential torque increase factor $\eta_T$ is approximately:

$$ \eta_T \approx \frac{F_{max}^{trad}}{F_{max}^{LSR}} $$

Analytical and Finite Element Analysis (FEA) models of a specific cycloidal drive geometry indicate that $\eta_T$ can realistically range from 1.3 to 1.7, meaning a 30% to 70% increase in torque capacity without changing material or major dimensions. Alternatively, for the same torque rating, the lifetime $L_{10}$ (the life at which 90% of units survive) can be dramatically extended. Using the standard bearing life equation adapted for pins, where life is proportional to the load cubed ($L \propto C^3 / P^3$), a reduction in maximum pin load by 20% leads to a life increase of $(1/0.8)^3 \approx 1.95$, or nearly double.

Synergistic Design Optimizations: The implementation of the LSR is not an isolated change. It allows for and synergizes with other optimizations in the cycloidal drive:

1. Pin and Lobe Profile Optimization: With a more predictable load distribution, the traditional cycloidal profile can be slightly modified to optimize contact stress (Hertzian stress) under the new force map. This might involve a small correction factor $\epsilon$ to the generating circle radius or a slight crowning of the lobe flanks.

2. Material and Heat Treatment: The increased capacity justifies the use of more advanced materials like case-hardened aerospace-grade steels or even specialty alloys for the cycloidal disks and pins, pushing the $S_{allowable}$ limit higher.

3. Lubrication and Thermal Management: Higher load capacity often generates more heat. Integrated cooling channels in the housing or advanced synthetic lubricants with solid additives (e.g., PTFE, graphene) become critical to maintain performance. The heat generation $Q$ can be estimated from efficiency $\eta$ and input power $P_{in}$: $Q = (1-\eta) P_{in}$. An improved design must manage this effectively.

4. Preload and Backlash Control: The LSR mechanism can also be designed with a slight preload adjustment, allowing for the compensation of minor wear over time and maintaining near-zero backlash, which is critical for servo applications. The preload force $F_{pre}$ introduces a initial stress state that must be accounted for in the total stress calculation: $\sigma_{total} = \sigma_{load} + \sigma_{pre}$.

Practical Implementation and Verification: The transition from analytical model to physical cycloidal drive requires careful attention to detail. The LSR must be made from a material with high stiffness and good wear resistance, such as through-hardened tool steel. Its mass should be minimized to reduce inertia. The assembly process becomes more involved, as the pins must be inserted through the cycloidal disks and then into the LSR simultaneously. This necessitates precision jigs and fixtures. Verification involves both strain-gauge testing on prototype pins to measure the force distribution directly and endurance testing under accelerated load cycles. The performance metrics to track include:

– Maximum operating temperature.

– Efficiency map across the torque-speed range.

– Noise and vibration spectra (which typically improve with better load sharing).

– Lifespan under peak load conditions.

In conclusion, the pursuit of enhanced load capacity for the cycloidal drive is a multifaceted engineering challenge that goes beyond simple material substitution. By addressing the fundamental mechanical flaw of uneven load distribution in the output stage through an integrated Load-Sharing Ring mechanism, a significant leap in performance is achievable. This approach enforces deformation compatibility among the load-carrying pins, transforming them from a group of independent cantilevers into a coordinated system. The analytical framework presented, involving coupled equilibrium, compatibility, and constitutive equations, provides a powerful tool for designing and optimizing such systems. The result is a cycloidal drive that not only bears higher loads but does so with greater reliability, smoother operation, and longer service life. This development pathway, focusing on intelligent load management rather than just brute force strengthening, represents a mature and promising direction for advancing this indispensable class of precision speed reducers. Future work may explore active or adaptive load-sharing systems and the integration of these principles into miniaturized or extreme-environment cycloidal drive units.