As an engineer deeply involved in the development and manufacturing of precision transmission systems, I have dedicated significant effort to understanding and improving the motion accuracy of Rotary Vector Reducers. These reducers, critical for robotic applications, demand exceptionally low motion error and backlash, often within a few arc-seconds. The challenge lies in the multitude of error factors that can degrade performance, even when individual components are manufactured with micron-level precision. Through my experience, I have found that a systematic approach—combining rigorous error analysis with tailored machining and assembly processes—is essential to achieve the required high motion accuracy in Rotary Vector Reducers under conventional production conditions. This article delves into the key error sources affecting the Rotary Vector Reducer and outlines the practical technical measures I have implemented to mitigate them, emphasizing the use of tables and formulas for clarity.

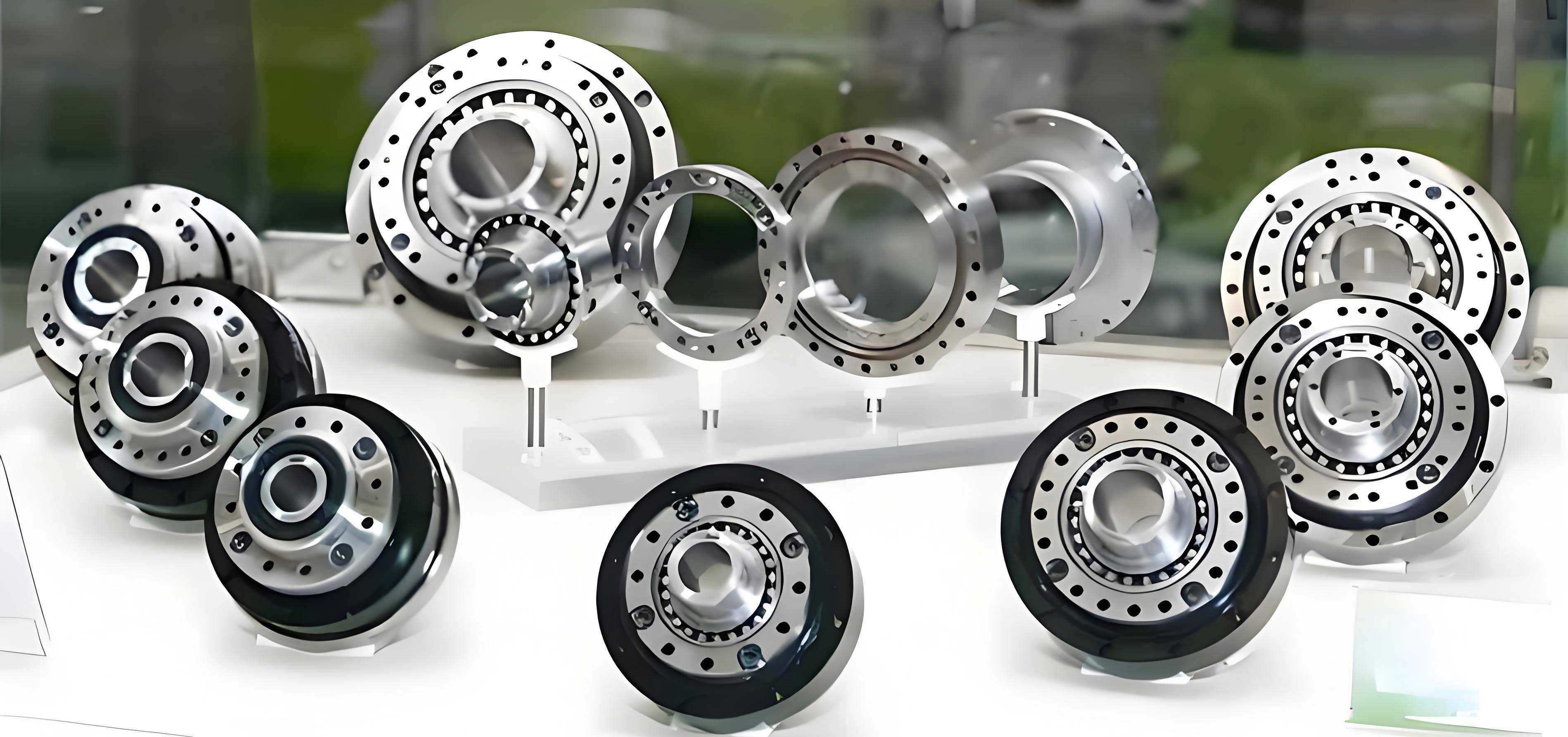

The Rotary Vector Reducer is a sophisticated two-stage planetary transmission device incorporating a cycloidal drive mechanism. Its high motion accuracy is paramount for applications like industrial robots, where positional repeatability and minimal backlash are non-negotiable. The target motion error and geometric backlash are typically around 1 arc-minute or less. However, the complex interaction of components in the Rotary Vector Reducer introduces numerous potential error sources. Primarily, these originate from the second reduction stage, involving the needle bearing shell (or pin housing), the cycloidal gears (or swing gears), the planet carrier (or crankshaft assembly), the eccentric shafts, and the associated bearings. Even if each part is fabricated with utmost care, assembling them without a strategic process often fails to meet the stringent assembly precision. My work has focused on identifying these error factors qualitatively and then devising machining and assembly protocols that leverage error cancellation and transfer techniques, enabling the production of high-accuracy Rotary Vector Reducers without relying on exotic manufacturing methods.

Comprehensive Analysis of Error Factors in Rotary Vector Reducers

To effectively control motion accuracy, one must first dissect the transmission chain of the Rotary Vector Reducer. The primary errors stem from geometric deviations in key components and their assemblies. Through kinematic analysis, I categorize these errors based on their periodicity—long-period errors that vary slowly over a revolution and short-period errors that fluctuate rapidly. This distinction is crucial for targeting corrective measures.

The major error contributors in a Rotary Vector Reducer include:

- Needle Bearing Shell: Positional errors among the pin holes (which house the needle pins) and the positional error of this pin hole group relative to the bearing bores that support the main bearings.

- Cycloidal Gear (Swing Wheel): Errors in the cycloidal tooth profile (the gear ring), positional errors among its three bearing bores (for the eccentric shaft bearings), and the positional error of the tooth profile relative to this trio of bearing bores.

- Planet Carrier (Output Flange): Positional errors among its three bearing bores (which house the eccentric shaft bearings) and the positional error of this bore group relative to the external cylindrical surface where the output bearing is mounted.

- Eccentric Shafts (typically three): Variations in the eccentricity values of the offset journals on the same side among the three shafts.

- Bearings: Radial runout errors of the various high-precision bearings used throughout the assembly.

The impact of these errors on the output motion is not uniform. For instance, errors like the misalignment of the pin hole group relative to the main bearing bores in the needle shell, or the misalignment of the cycloidal tooth profile relative to its bearing bores, introduce a once-per-revolution error component. This manifests as a long-period motion error. Conversely, differences in eccentricity among the three eccentric shafts create an error that repeats multiple times per output revolution, leading to a short-period error. This was confirmed through motion error testing and spectral analysis on prototype Rotary Vector Reducers, where the measured error spectra showed distinct peaks corresponding to these predicted frequencies.

To summarize these relationships systematically, I have found tables and formulas invaluable. The table below categorizes the primary error sources and their characteristics.

| Component | Specific Error Source | Nature of Induced Motion Error | Mathematical Representation (Simplified) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Needle Bearing Shell | Eccentricity of pin hole group relative to main bearing axis | Long-period (1st order) | $$ \Delta \theta_{L1} = k_1 \cdot e_{p} \cdot \sin(\phi_{p} + \Omega t) $$ |

| Cycloidal Gear | Radial runout of tooth profile relative to bearing bore center | Long-period (1st order) | $$ \Delta \theta_{L2} = k_2 \cdot \delta_{c} \cdot \sin(\phi_{c} + \Omega t) $$ |

| Planet Carrier | Eccentricity of bearing bore group relative to output axis | Long-period (1st order) | $$ \Delta \theta_{L3} = k_3 \cdot e_{ca} \cdot \sin(\phi_{ca} + \Omega t) $$ |

| Eccentric Shafts (Set of 3) | Difference in eccentricity (Δe) between shafts on same side | Short-period (3rd order or higher) | $$ \Delta \theta_{S} = \sum_{n=3,6,…} k_{sn} \cdot \Delta e \cdot \sin(n \cdot Z_c \cdot \omega t + \psi_n) $$ |

| Bearings | Radial runout of main and eccentric shaft bearings | Both Long & Short-period (depends on mounting) | $$ \Delta \theta_{B} = \sum_m k_{bm} \cdot r_{bm} \cdot \sin(m \cdot \omega_b t + \phi_{bm}) $$ |

Where:

- $\Delta \theta$ represents the output angular error.

- $e_p, \delta_c, e_{ca}$ are eccentricity/runout magnitudes for pin hole group, cycloidal gear, and carrier bore group, respectively.

- $\Delta e$ is the maximum difference in eccentricity among the three eccentric shafts.

- $r_{bm}$ is the radial runout magnitude of bearings.

- $\phi$ terms are phase angles.

- $\Omega$, $\omega$, $\omega_b$ are rotational frequencies.

- $Z_c$ is the number of teeth on the cycloidal gear.

- $k$ coefficients are transmission ratios and sensitivity factors specific to the Rotary Vector Reducer geometry.

The total motion error of the Rotary Vector Reducer can be approximated as the vector sum of these individual error components:

$$ \Delta \theta_{total} \approx \vec{\Delta \theta_{L}} + \vec{\Delta \theta_{S}} $$

with $\vec{\Delta \theta_{L}} = \Delta \theta_{L1} + \Delta \theta_{L2} + \Delta \theta_{L3}$ and $\vec{\Delta \theta_{S}} \approx \Delta \theta_{S} + \Delta \theta_{B}^{(short)}$. The phase relationships are critical, as they determine whether errors accumulate or partially cancel.

Machining Process Measures for High-Accuracy Components

Given the analysis, simply machining every part to its tightest possible tolerance is neither practical nor always necessary. The philosophy I adopt is to control the errors that matter most for the final assembly, often focusing on the relative accuracy between mating parts rather than absolute individual precision. This is where error transfer and initial error minimization strategies come into play for the Rotary Vector Reducer.

1. Machining of Bearing Bores in Cycloidal Gears and Planet Carrier:

The three bearing bores in the cycloidal gear and the planet carrier must have high mutual positional accuracy. However, kinematic analysis reveals that the critical requirement is the consistency between the two sets of three bores, not necessarily each set having perfect absolute position. Therefore, I employ a matched machining technique. First, the three bores in the cycloidal gear are precisely machined on a high-precision jig boring machine or coordinate measuring machine (CMM)-guided machining center. Then, using the finished cycloidal gear as a master template, the machine tool’s spindle position is meticulously set to match the actual bore positions. The planet carrier’s three bores are subsequently machined in the same setup. This ensures the bore patterns in both parts are congruent, minimizing the relative error that would cause misalignment in the assembled Rotary Vector Reducer.

2. Grinding of Eccentric Shafts:

The three eccentric shafts are pivotal. The difference in eccentricity ($\Delta e$) between the offset journals on the same side of different shafts directly causes short-period error. The goal is not just to keep each shaft’s eccentricity within tolerance (e.g., ±2 µm), but to make the eccentricities of all three shafts as similar as possible. I specify a group-matching process. After grinding, the eccentricity of each journal is precisely measured. Shafts are then sorted into groups where the actual eccentricity values are closely matched—all slightly positive or all slightly negative relative to the nominal. For a set of three shafts destined for one Rotary Vector Reducer, selecting shafts with minimal $\Delta e$ is a standard practice. The relationship can be expressed as:

$$ \Delta e_{critical} = \max(|e_{A} – e_{B}|, |e_{B} – e_{C}|, |e_{C} – e_{A}|) $$

where $e_{A}, e_{B}, e_{C}$ are the actual eccentricities of the three shafts. We aim for $\Delta e_{critical} < T$, where $T$ is a very small threshold, often a fraction of the individual tolerance.

3. Machining of Pin Holes in the Needle Bearing Shell:

This part presents a unique challenge: a ring of many small-diameter, high-precision semi-circular pin holes with a high length-to-diameter ratio. Conventional drilling or reaming struggles with tool deflection and consistency. My solution involves precision boring on a jig borer, but with a custom fixture. A dedicated mandrel, hardened to match the shell’s material, is inserted into the large central bore of the shell. This mandrel effectively converts the semi-circular holes into full circular holes for the boring tool, providing full support and eliminating tool deflection. After machining, the mandrel is removed. This process, followed by verification on a CMM, consistently yields pin hole position accuracy within microns for the Rotary Vector Reducer.

4. General Precision Machining Philosophy:

For all critical surfaces, I emphasize stability, thermal control, and in-process measurement. The use of CNC machines with glass scale feedback and temperature compensation is standard. Furthermore, I often apply the principle of datum consistency: where possible, all critical features on a part are machined in a single setup or relative to the same datum set to minimize error stacking.

| Component | Critical Feature | Machining Challenge | Adopted Process Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycloidal Gear | Three bearing bores & tooth profile | High positional accuracy of bore trio relative to teeth | Finish boring bores first using high-precision bore machining, then grind teeth using bore centers as datum. |

| Planet Carrier | Three bearing bores | Matching pattern to cycloidal gear bores | Matched machining using finished cycloidal gear as template on same machine setup. |

| Eccentric Shafts | Eccentric journal dimensions and phase | Minimizing eccentricity variation among a set of three | Precision grinding with post-measurement and selective grouping/matching based on actual eccentricity values. |

| Needle Bearing Shell | Semi-circular pin holes | Precision and consistency of many small, deep half-holes | Boring with full-circular support mandrel fixture on jig borer/coordinated CNC. |

| All Components | Geometric tolerances (cylindricity, roundness) | Achieving sub-micron form accuracy | Employ precision grinding, honing, or lapping with real-time form measurement feedback. |

Assembly Process Measures: Error Cancellation and Adjustment

Precision machining alone is insufficient. The assembly phase is where the final motion accuracy of the Rotary Vector Reducer is realized. I employ an active error cancellation adjustment assembly method. This involves meticulously measuring the magnitude and phase of key errors on individual components and bearings, then strategically orienting these components during assembly so that their error vectors partially or fully oppose each other.

The process involves three key steps:

Step 1: Precision Measurement and Phasing Marking.

Before assembly, I measure and record the following for relevant parts:

- For the needle bearing shell: The eccentricity vector ($\vec{e_p}$) of the pin hole group relative to the main bearing axis. This includes magnitude and angular phase.

- For each cycloidal gear: The radial runout vector ($\vec{\delta_c}$) of the tooth profile relative to the center defined by its three bearing bores.

- For the planet carrier: The eccentricity vector ($\vec{e_{ca}}$) of its three bearing bore group relative to its external mounting diameter.

- For each eccentric shaft: The actual eccentricity value and the angular phase of its offset journals.

- For each critical bearing (e.g., the main bearings and the six eccentric shaft bearings): The radial runout vector ($\vec{r_b}$), including the magnitude and the location of the maximum runout point.

These measurements are typically done using high-resolution CMMs and precision rotary tables for phase determination.

Step 2: Strategic Orientation and Assembly.

During assembly, I adjust the angular orientation (phase) of components to achieve error vector cancellation. Two primary techniques are used:

A) Cancellation of Long-Period Errors:

The goal is to minimize the sum $\vec{\Delta \theta_L} = k_1\vec{e_p} + k_2\vec{\delta_c} + k_3\vec{e_{ca}} + \vec{\Delta \theta_{B(long)}}$. Since the bearing runout $\vec{r_b}$ can be oriented, it serves as a powerful adjustment variable. For instance, when installing the main bearings into the needle shell and onto the planet carrier, I orient them so that their runout vectors counteract the measured eccentricities of the shell and carrier. Similarly, the cycloidal gear is mounted on its eccentric shafts with a specific angular orientation relative to the carrier to make $\vec{\delta_c}$ oppose the other long-period error components. The optimal orientation is found by solving a vector equation:

$$ \text{Minimize } |\vec{R}_{target} + \vec{R}_{adjustable}| $$

where $\vec{R}_{target}$ is the sum of fixed part errors and $\vec{R}_{adjustable}$ is the contribution from orientable bearings and components.

B) Cancellation of Short-Period Errors:

The short-period error primarily from eccentric shaft differences ($\Delta e$) can also be mitigated by bearing orientation. The radial runout of the six eccentric shaft bearings can be phased to generate a compensating motion that offsets the kinematic error induced by $\Delta e$. This requires understanding the transmission path and often involves iterative adjustment or simulation-based pre-determination of optimal bearing phases.

Step 3: Controlled Preloading.

The stiffness and uniformity of bearing preload significantly affect the motion accuracy and backlash of the Rotary Vector Reducer. I achieve this through selective fitting of precision ground spacers and controlled tightening of preload screws. A critical aspect is ensuring uniform preload across all bearing sets (e.g., the two main bearings and the six eccentric shaft bearings) to prevent uneven deflection that introduces its own errors. The preload force $F_{preload}$ is carefully calibrated to balance stiffness against excessive friction and heat generation, often following:

$$ F_{preload} = C \cdot \sqrt[3]{d_m} $$

where $C$ is an empirical constant based on bearing type and speed, and $d_m$ is the bearing mean diameter. Torque-controlled wrenches are used to ensure screw preload consistency.

| Target Error Type | Error Sources to Cancel | Adjustment (Compensation) Variable | Assembly Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Period Error | $ \vec{e_p}$ (Shell), $\vec{\delta_c}$ (Gear), $\vec{e_{ca}}$ (Carrier) | Angular orientation of main bearings and cycloidal gear on eccentric shafts. | Orient main bearings so their runout vectors oppose the measured $\vec{e_p}$ and $\vec{e_{ca}}$. Mount cycloidal gear at an angle where $\vec{\delta_c}$ counteracts the residual sum. |

| Short-Period Error | $\Delta e$ (Eccentric shaft set difference) | Angular orientation of the six eccentric shaft bearings. | Phase the eccentric shaft bearings such that their combined runout induces a compensating 3rd-order harmonic that negates the error from $\Delta e$. |

| Backlash & Stiffness | Bearing clearance, gear mesh clearance | Preload force via spacer thickness and screw torque. | Precisely grind spacers to achieve nominal preload. Use torque wrench for uniform screw tightening in a star pattern. |

The effectiveness of this assembly approach for the Rotary Vector Reducer can be modeled. If we consider the long-period error cancellation, the residual error after assembly $\epsilon_{res}$ is:

$$ \epsilon_{res} = | \sum_{i=1}^{n} (k_i \cdot \vec{E_i} \cdot e^{j\phi_i}) + \sum_{j=1}^{m} (k_{bj} \cdot \vec{R_j} \cdot e^{j(\phi_{bj} + \alpha_j)}) | $$

where $\vec{E_i}$ are part error vectors with phases $\phi_i$, $\vec{R_j}$ are bearing runout vectors with inherent phases $\phi_{bj}$, and $\alpha_j$ are the adjustable assembly rotation angles we apply. The optimization problem is to choose $\alpha_j$ to minimize $\epsilon_{res}$. In practice, this is often done via look-up tables derived from measurement data or simple software aids.

Conclusion: Integrating Analysis and Precision Craftsmanship

Guaranteeing the high motion accuracy of a Rotary Vector Reducer is a multifaceted endeavor that bridges theoretical error analysis with practical manufacturing artistry. My experience confirms that simply imposing ultra-tight tolerances on every component is neither efficient nor always effective. Instead, a smarter approach focuses on understanding the kinematic significance of each error source—distinguishing between long-period and short-period contributors—and then implementing targeted machining and assembly processes to control them.

The machining measures, such as matched boring of the cycloidal gear and planet carrier bores, grouped selection of eccentric shafts, and fixture-based machining of pin holes, address error at the component level by enhancing relative accuracy and minimizing critical error variations. The assembly process then elevates this further through the deliberate error cancellation adjustment method. By treating high-precision bearings as adjustable compensation elements and strategically phasing components based on pre-measured error data, we can actively reduce the compounded error in the final Rotary Vector Reducer assembly. This holistic methodology, combining meticulous measurement, strategic machining, and intelligent assembly, has proven successful in achieving motion accuracy levels of around 1 arc-minute in Rotary Vector Reducers produced under conventional workshop conditions. It underscores the principle that in precision engineering, system-level thinking and process control are just as important as the precision of the individual parts themselves. The continued refinement of these techniques remains central to advancing the performance and reliability of Rotary Vector Reducers in demanding robotic and precision motion applications.

Future work may involve more sophisticated statistical process control (SPC) for the machining steps and the development of automated assembly systems that can precisely rotate components to calculated optimal angles based on real-time measurement feedback, pushing the accuracy boundaries of the Rotary Vector Reducer even further.