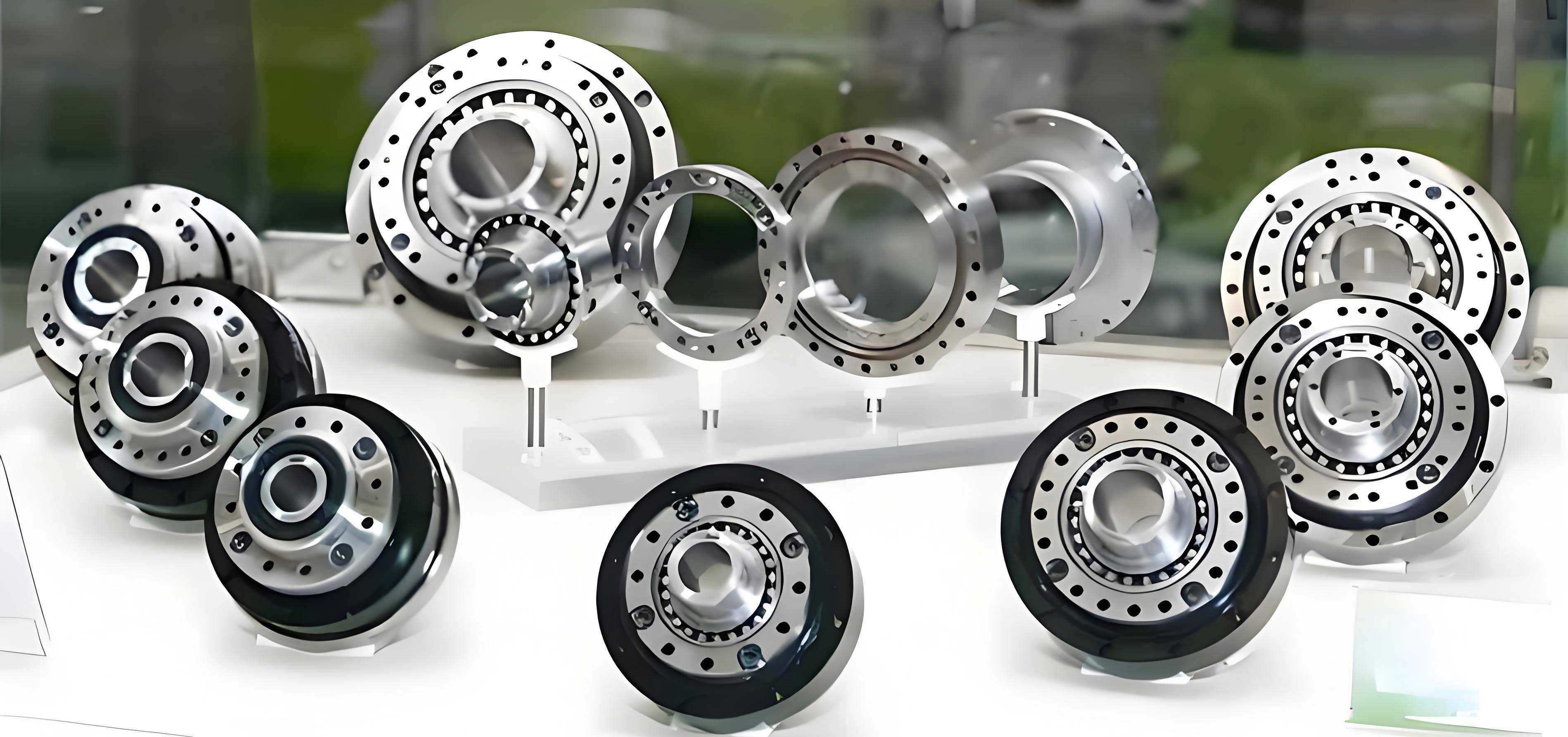

The rotary vector reducer, a pivotal component in modern precision machinery, stands out for its exceptional capabilities in high-ratio speed reduction, substantial load-bearing capacity, impressive torsional stiffness, and extended operational lifespan. These attributes make it the preferred transmission solution for critical applications such as industrial robot arm joints, high-precision computer numerical control (CNC) machine tools, and various sophisticated automation systems. As global manufacturing trends towards greater precision and intelligence, the demand for superior transmission accuracy in these reducers has intensified. While domestic research and production of rotary vector reducers have made significant strides, a performance gap, particularly in critical metrics like backlash and positional repeatability, persists when compared with leading international products. Therefore, a systematic and in-depth investigation into the transmission error mechanisms of the cycloid-pin gear based rotary vector reducer is of paramount theoretical importance and practical value for advancing domestic manufacturing capabilities.

The quest for understanding and minimizing errors in gear systems has a long history. Early research focused on fundamental planetary cycloid drives, analyzing their kinematic accuracy and the influence of manufacturing tolerances on transmission ratio variation, leading to the derivation of relationships between gear backlash, transmission ratio, and torque. Subsequent studies established comprehensive mechanical models for the rotary vector reducer, employing equivalent mass-spring models to create mathematical frameworks for analyzing error propagation. These works explored the individual and combined effects of various machining and assembly errors on overall transmission precision. In parallel, extensive research has been conducted on the transmission accuracy of these reducers. Key contributions include the development of formulas linking meshing errors to transmission accuracy based on the engagement relationship between the cycloid disc and the pin gear, introducing the concept of comprehensive meshing error for assessment. Other studies analyzed the dynamic load-induced deformations in components like the cycloid disc, pin gear, and crank pins, deriving calculation methods for rotational error under load. Furthermore, analyses have detailed the impact of specific errors—such as pin gear machining errors, cycloid disc pitch accumulation errors, eccentricity errors, and planetary carrier assembly errors—on the output rotation angle. More recent methodologies leverage principles like the action line increment theory and error transfer matrices to quantify how primitive errors in sub-assemblies affect the final output angle error. Studies have also developed allocation models for static backlash, considering up to fifteen different error sources, and validated them through simulation software. However, a comprehensive model that seamlessly integrates the unique two-stage transmission characteristics and the complete error propagation path of the rotary vector reducer from input to output, while accounting for feedback effects, remained an area for further elaboration.

This article addresses this need by presenting a holistic error analysis of the industrial robot rotary vector reducer. By integrating the meshing characteristics of its first-stage involute planetary gear set and second-stage cycloid-pin gear planetary mechanism, we systematically analyze the influence of primitive errors inherent in all major components on the system’s output angular displacement. This forms the foundation for a comprehensive error transmission analysis model. This model explicitly delineates the correspondence between various original errors and the final output error of the mechanism. The validity and practical implications of the model are then demonstrated through a detailed numerical case study of an RV-40E type reducer and supporting experimental analysis.

Structural Composition and Operational Principle of the Rotary Vector Reducer

The rotary vector reducer achieves its high reduction ratio through a compound two-stage planetary system. The architecture and power flow are fundamental to understanding its error sources.

Stage 1: Involute Planetary Gear Reduction. External motive power is introduced via the input shaft, which is connected to the central sun gear. This sun gear meshes with multiple planet gears (typically two or three), arranged around it and housed within a planetary carrier. In the standard rotary vector reducer configuration, the ring gear is fixed. Consequently, the rotation of the sun gear drives the planet gears to revolve around their own axes and orbit the sun gear. This planetary motion results in the rotation of the planetary carrier. The primary speed reduction occurs at this stage. The transmission ratio \( i_1 \) for this stage with a fixed ring gear is given by:

$$ i_1 = 1 + \frac{N_r}{N_s} $$

where \( N_r \) is the number of teeth on the fixed ring gear and \( N_s \) is the number of teeth on the sun gear. The planet gears are rigidly connected to the crank pins of the second stage.

Stage 2: Cycloid-Pin Gear Planetary Reduction. The rotation of the planetary carrier and its attached planet gears serves as the input to the second stage. Each planet gear is connected to an eccentric crankshaft. As the planet gear rotates, it imparts an eccentric motion to the cycloid disc(s) mounted on these crankshafts via bearings. The cycloid disc, with its lobed profile, meshes with a stationary circular array of pin gears (or pin teeth) housed in the pin gear shell. Due to this unique geometry and the constraint provided by the pins, the eccentric motion of the cycloid disc is transformed. For each revolution of the crankshaft (and thus the planet gear), the cycloid disc undergoes a combination of a planetary revolution (epicyclic motion) around the central axis and a slow relative rotation about its own axis. The direction of this slow rotation is opposite to that of the crankshaft. The magnitude of this rotation for a single-stage cycloid drive is:

$$ \Delta \theta_{cycloid} = -\frac{1}{N_p – N_c} \cdot \theta_{crank} $$

where \( N_c \) is the number of lobes on the cycloid disc, \( N_p \) is the number of pin gears, and \( \theta_{crank} \) is the crankshaft rotation angle. Typically, \( N_p – N_c = 1 \) (single-tooth difference), leading to a high reduction ratio. The slow rotation of the cycloid disc is the effective output of the second stage.

Output Mechanism. The rotation of the cycloid disc(s) is extracted by an output mechanism. This usually consists of an output flange or plate connected to the cycloid disc via a set of pins or rollers located in holes on the disc and corresponding holes on the output flange. This arrangement, often called a W-mechanism or pin-in-hole coupling, transmits the cycloid disc’s rotation to the output shaft while compensating for the disc’s eccentric orbital motion. Thus, the final output is the rotation of the output flange/shaft. The total reduction ratio \( i_{total} \) of the rotary vector reducer is the product of the two stages:

$$ i_{total} = i_1 \cdot i_2 = \left(1 + \frac{N_r}{N_s}\right) \cdot (N_p – N_c) $$

Given typical values, this results in very high reduction ratios ranging from approximately 30 to over 200.

Fundamentals of the Error Analysis Methodology

The core methodology employed here is the Action Line Increment Principle, which provides a powerful and systematic vectorial approach to error propagation in mechanisms. Consider a simplified pair of elements, where Body 1 is the driver and Body 3 is the follower. The error analysis model for such a system is based on projecting geometric errors onto relevant kinematic directions.

Let \( \mathbf{n}_1 \) denote the unit vector along the action line—the direction of force transmission or kinematic constraint at the point of contact or connection between the driver and follower. Let \( \mathbf{n}_2 \) denote the unit vector along the motion line—the instantaneous tangential direction of the follower’s motion trajectory at the reference point.

Any primitive geometric error in a component, such as an eccentricity or profile deviation, can be represented as a displacement error vector \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_i \). The process of determining how this error affects the follower’s position involves two sequential projections:

- Projection onto the Action Line: The component of the error vector that affects the kinematic constraint is found by projecting \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_i \) onto \( \mathbf{n}_1 \). This yields the effective error along the line of action: \( \mathbf{n}_1 \cdot \boldsymbol{\delta}_i \).

- Projection onto the Motion Line: This effective action-line error is then converted into an equivalent displacement error along the follower’s path of motion. This conversion involves dividing by the cosine of the angle between the action line and the motion line, which is mathematically equivalent to projecting onto the motion line after scaling. The resulting equivalent follower position error \( \sigma_i \) due to \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_i \) is given by:

$$ \sigma_i = \frac{\mathbf{n}_1 \cdot \boldsymbol{\delta}_i}{\mathbf{n}_1 \cdot \mathbf{n}_2} $$

The denominator \( \mathbf{n}_1 \cdot \mathbf{n}_2 \) represents the cosine of the pressure angle in gear meshes.

This principle allows for the aggregation of errors from multiple sources by vector summation before projection.

Systematic Coordinate Frames and Error Modeling for the Rotary Vector Reducer

To apply the action line increment principle comprehensively, a unified coordinate system for the entire rotary vector reducer is established. The global reference frame \( O_0X_0Y_0 \) is fixed to the reducer housing, with its origin \( O_0 \) at the center of the pin gear circle (the theoretical axis of the output). For each major component \( i \) (sun gear, planet gear, crankshaft, cycloid disc, output plate), a local moving coordinate frame \( O_iX_iY_i \) is attached to its center of rotation or geometric center. The transformation from a local frame \( i \) to the global frame \( 0 \) is described by a homogeneous transformation matrix \( \mathbf{C}_{0i} \), which accounts for both the component’s rotation angle \( \theta_i \) and any fixed positional offsets.

| Frame | Origin Attached To | Key Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| \( O_0X_0Y_0 \) | Housing / Pin Gear Center | Global reference frame |

| \( O_1X_1Y_1 \) | Sun Gear Center | Input stage reference |

| \( O_2X_2Y_2 \) | Planet Gear Center | First-stage output / Second-stage input |

| \( O_3X_3Y_3 \) | Crankshaft Geometric Center | Eccentric motion reference |

| \( O_4X_4Y_4 \) | Cycloid Disc Geometric Center | Cycloid motion reference |

| \( O_6X_6Y_6 \) | Output Plate Center | Final output reference |

The overall transmission error is derived by modeling the error propagation through each of the four functional sub-assemblies: the involute gear stage, the parallelogram input linkage (crank mechanism), the cycloid-pin gear mesh, and the output pin coupling. The output error of one stage becomes an input error to the next.

1. Error Model for the Involute Planetary Gear Stage

At any instant, with the sun gear rotated by \( \theta_1 \), the meshing point between the sun gear and a planet gear is considered. The action line \( \mathbf{n}_{11} \) is the common normal to the tooth profiles at the mesh point, which, for involute gears, is fixed in direction relative to the line of centers and defined by the pressure angle \( \alpha \). In the global frame:

$$ \mathbf{n}_{11} = [-\cos\alpha, -\sin\alpha]^T $$

The motion line \( \mathbf{n}_{12} \) is the common tangent direction at the pitch circles.

The primary error considered here is the center distance error \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{11} \), which could arise from bearing clearances or housing machining inaccuracies. This error modifies the effective position of the planet gear center. Applying the action line increment principle, the induced error in the planet gear’s rotation angle \( \Delta \theta_1^{(I)} \) is:

$$ \Delta \theta_1^{(I)} = \frac{\mathbf{n}_{11} \cdot (\mathbf{C}_{02} \boldsymbol{\delta}_{11})}{r_2 \cos \alpha} $$

where \( r_2 \) is the operating pitch radius of the planet gear, and \( r_2 \cos \alpha \) is the instantaneous lever arm (perpendicular distance from the planet center to the line of action).

2. Error Model for the Parallelogram Input Linkage

This stage transfers rotation from the planet gear to the eccentric motion of the crankshaft. Since the planet gear and crankshaft are rigidly connected, their rotational errors are identical. However, geometric errors in the crankshaft’s eccentric segment directly affect the input to the cycloid stage. The action line \( \mathbf{n}_{12} \) for this four-bar linkage is perpendicular to the eccentric direction of the crankshaft, as it transmits torque via tangential force. The motion line \( \mathbf{n}_{22} \) for the cycloid disc’s revolution is aligned with the tangent to its orbital path. In the global frame, for a crankshaft angle \( \theta_3 \) and initial phase \( \psi \):

$$ \mathbf{n}_{12} = \mathbf{n}_{22} = [\sin(\theta_3 + \psi), -\cos(\theta_3 + \psi)]^T $$

A key error here is the crankshaft eccentricity error \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{21} \), which alters the effective eccentric distance \( a \). This error causes a direct displacement of the cycloid disc center. The resulting error in the cycloid disc’s revolution angle \( \Delta \theta_2^{(P)} \) is:

$$ \Delta \theta_2^{(P)} = \frac{\mathbf{n}_{12} \cdot (\mathbf{C}_{03} \boldsymbol{\delta}_{21})}{a} $$

where \( a \) is the nominal eccentricity of the crankshaft.

3. Error Model for the Cycloid-Pin Gear Meshing Stage

This is the most critical stage for precision in the rotary vector reducer. The analysis considers a meshing point between the cycloid disc tooth and a pin. The action line \( \mathbf{n}_{13} \) is the normal to the cycloid tooth profile at the contact point. The motion line \( \mathbf{n}_{23} \) is perpendicular to the radius vector from the cycloid disc’s center to the contact point.

Let \( \mathbf{r} \) be the position vector of the contact point on the cycloid profile relative to \( O_0 \), derivable from the trochoidal generation equation. Let \( \mathbf{r}_p \) be the vector from \( O_0 \) to the pin center. The unit normal \( \mathbf{n}_{13} \) can be derived from the profile geometry. The pressure angle \( \alpha_3 \) varies during engagement. A significant error source is the cycloid tooth profile error \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{31} \), which acts along the profile normal direction \( \mathbf{n}_{13} \). The induced error in the cycloid disc’s rotation (its slow self-rotation) \( \Delta \theta_3^{(C)} \) is:

$$ \Delta \theta_3^{(C)} = \frac{\mathbf{E}_3}{r \cos \alpha_3} \left( \sum \mathbf{C}_{0i} \boldsymbol{\delta}_{3i} \right) $$

where \( \mathbf{E}_3 = \frac{\mathbf{n}_{13}}{\mathbf{n}_{13} \cdot \mathbf{n}_{23}} \), \( r \) is the magnitude of the contact point radius vector, and the summation includes profile errors and pin position errors.

4. Error Model for the Output Pin Coupling Mechanism

This mechanism transfers the cycloid disc’s rotation to the output plate while accommodating the disc’s orbital motion. The connecting pins experience tangential forces. Therefore, the action line \( \mathbf{n}_{14} \) and the motion line \( \mathbf{n}_{24} \) for the output plate’s rotation are coincident and tangential to the circle on which the coupling pins are located. In the global frame, with the output plate rotated by \( \theta_6 \):

$$ \mathbf{n}_{14} = \mathbf{n}_{24} = [-\sin\theta_6, \cos\theta_6]^T $$

A crucial manufacturing error is the position error (eccentricity) of the pin holes on the output plate, denoted \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{41} \). This error directly displaces the point of force application. The resulting error in the output plate angle \( \Delta \theta_4^{(O)} \) is:

$$ \Delta \theta_4^{(O)} = \frac{\mathbf{n}_{14} \cdot (\mathbf{C}_{06} \boldsymbol{\delta}_{41})}{r_6} $$

where \( r_6 \) is the radius of the circle on which the coupling pins are mounted on the output plate.

5. Synthesis of System Error and Feedback Effect

The total output error is the sum of the contributions from all stages, considering their respective transmission ratios. Errors from the first involute stage and the parallelogram input stage are reduced by the second-stage cycloid ratio before appearing at the output. Errors from the cycloid mesh and output coupling appear directly at the output. Therefore, the preliminary system output error \( \Delta \Theta \) is:

$$ \Delta \Theta = \Delta \theta_1^{(I)} \cdot \frac{1}{i_2} + \Delta \theta_2^{(P)} \cdot \frac{1}{i_2} + \Delta \theta_3^{(C)} + \Delta \theta_4^{(O)} $$

where \( i_2 = N_p – N_c \).

Critical Feedback Error: In the rotary vector reducer, the output plate is typically rigidly connected to the planetary carrier of the first stage. Consequently, any angular error \( \Delta \Theta \) in the output plate causes a proportional rotational displacement of the planetary carrier. This displacement is fed back into the first-stage involute gear mesh, altering the meshing condition and generating an additional error. This feedback error vector \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_f \) in the output plate frame \( O_6X_6Y_6 \) is:

$$ \boldsymbol{\delta}_f = \Delta \Theta \cdot (r_1 + r_2) \cdot [0, 1]^T $$

where \( (r_1 + r_2) \) is the nominal center distance between the sun and planet gears. Projecting this feedback error through the involute stage model yields an additional planet gear rotation error \( \Delta \theta_{1f} \):

$$ \Delta \theta_{1f} = \frac{\mathbf{n}_{11} \cdot (\mathbf{C}_{06} \boldsymbol{\delta}_f)}{r_2 \cos \alpha} $$

This feedback error is also reduced by the cycloid ratio when it reaches the output. Therefore, the complete and final system output error \( \Delta \Theta_{total} \), accounting for feedback, is:

$$ \Delta \Theta_{total} = \left( \Delta \theta_1^{(I)} + \Delta \theta_{1f} \right) \cdot \frac{1}{i_2} + \Delta \theta_2^{(P)} \cdot \frac{1}{i_2} + \Delta \theta_3^{(C)} + \Delta \theta_4^{(O)} $$

This equation represents the comprehensive error transmission model for the rotary vector reducer.

| Sub-Assembly | Typical Primitive Error | Symbol | Primary Effect | Governing Equation Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involute Stage | Center Distance Error | \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{11} \) | Alters planet gear position | \( \Delta \theta_1^{(I)} \) |

| Input Linkage | Crankshaft Eccentricity Error | \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{21} \) | Changes effective crank length | \( \Delta \theta_2^{(P)} \) |

| Cycloid Mesh | Cycloid Tooth Profile Error | \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{31} \) | Disrupts ideal rolling contact | \( \Delta \theta_3^{(C)} \) |

| Output Coupling | Output Plate Hole Position Error | \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{41} \) | Directly offsets output lever arm | \( \Delta \theta_4^{(O)} \) |

| System Feedback | Output Rotation (via Carrier) | \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_f \) | Modifies first-stage meshing | \( \Delta \theta_{1f} \) |

Case Study: Numerical Simulation for an RV-40E Reducer

To quantify the influence of different errors, a numerical analysis was performed using the parameters of a common model, the RV-40E rotary vector reducer.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Sun Gear Teeth | \( N_s \) | 9 |

| Planet Gear Teeth | \( N_p \) | 27 |

| Involute Pressure Angle | \( \alpha \) | 20° |

| Cycloid Disc Lobes | \( N_c \) | 39 |

| Pin Gear Teeth | \( N_p \) | 40 |

| Pin Gear Center Circle Radius | \( R_p \) | 64 mm |

| Crankshaft Eccentricity | \( a \) | 1.25 mm |

| Output Pin Circle Radius | \( r_6 \) | 27 mm |

| Stage 1 Ratio | \( i_1 \) | 4 |

| Stage 2 Ratio | \( i_2 \) | 41 |

| Total Ratio | \( i_{total} \) | 164 |

Four representative primitive errors, each with a magnitude of 5 microns (0.005 mm), were analyzed individually:

- \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{11} \): Center distance error in the involute stage.

- \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{21} \): Crankshaft eccentricity error.

- \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{31} \): Cycloid tooth profile error (simplified as a constant normal deviation).

- \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{41} \): Output plate pin hole position error (eccentricity).

The models from the previous section were solved computationally over one full revolution of the output shaft.

| Error Source | Peak-to-Peak Output Error ΔΘ” | Relative Influence | Characteristic Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Output Plate Hole Error (\( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{41} \)) | ~30.5″ | Largest | Sinusoidal, 1 cycle/rev (1st order) |

| Cycloid Profile Error (\( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{31} \)) | ~12.8″ | High | Complex, multi-cyclical (Nc order) |

| Crankshaft Eccentricity Error (\( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{21} \)) | ~8.2″ | Medium | Sinusoidal, 1 cycle/rev |

| Involute Center Distance Error (\( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{11} \)) | ~0.9″ | Smallest | Nearly constant, very small amplitude |

The results are clear and significant:

- Output Plate Hole Error (\( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{41} \)) has the most pronounced effect on the output angle of the rotary vector reducer. Since this error acts directly on the output mechanism with a 1:1 relationship (no reduction from the cycloid stage), it is not attenuated. It manifests as a first-order (once-per-revolution) sinusoidal error.

- Cycloid Tooth Profile Error (\( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{31} \)) ranks second in impact. It directly affects the fundamental kinematic conversion in the high-ratio second stage. Its effect on the output is multi-cyclical, related to the number of cycloid teeth, leading to a more complex error signature.

- Crankshaft Eccentricity Error (\( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{21} \)) has a medium influence. It modifies the input conditions to the cycloid stage, effectively changing the “link length” in the four-bar linkage model, which introduces a primarily first-order error component after being divided by the large reduction ratio \( i_2 \).

- Involute Stage Center Distance Error (\( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{11} \)) has a negligible effect on the final output in this simulation. Its influence is greatly diminished by the large second-stage reduction ratio (\( i_2 = 41 \)).

Furthermore, the analysis of the feedback error \( \Delta \theta_{1f} \) shows that while its magnitude is small (adding roughly 1-2 arc-seconds to the total error in this case), it is systematic and non-zero. For ultra-high-precision applications of the rotary vector reducer, this feedback loop effect is non-negligible and must be included in a complete error budget.

Experimental Validation and Spectral Analysis

To validate the model, an experimental test platform for transmission error was constructed. A servo motor drives the input of the rotary vector reducer prototype (RV-40E). A torque sensor monitors input torque, while a high-resolution rotary encoder (e.g., a precision optical grating) measures the output angular position. A magnetic powder brake provides a controllable load. Data from the encoder is processed to compute the kinematic transmission error (TE), defined as the difference between the actual output position and the theoretically ideal output position for a given input.

The measured transmission error over several output revolutions exhibits a complex periodic waveform. A Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) spectral analysis of this signal reveals the frequency components of the error, which can be directly correlated with specific mechanical error sources.

| Spectral Peak | Frequency (cycles/degree) | Period (in output degrees) | Correlated Mechanical Source (Inference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (Highest Amp.) | 0.00278 | ~360° | Assembly Backlash / Eccentricity (1st order error: \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{41} \), \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{21} \)) |

| 2nd | 0.108 | ~9.26° | Cycloid Mesh Frequency (\( N_c = 39 \) lobes over 360° ≈ 9.23° period) related to \( \boldsymbol{\delta}_{31} \), pin position errors. |

| Higher Orders | Multiples & Combinations | – | Crankshaft harmonics, bearing errors, pin hole errors, manufacturing imperfections. |

The experimental spectral analysis strongly supports the numerical findings. The dominant first-order error correlates with sources like output plate hole error and crankshaft error. The distinct peak at the cycloid mesh frequency confirms the significant role of cycloid-related errors like profile inaccuracies or pin position cumulative error. This empirical evidence validates the structure and predictions of the derived error transmission model for the rotary vector reducer.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This study has developed a comprehensive, integrated error transmission model for the industrial robot rotary vector reducer based on the action line increment principle. By establishing a unified coordinate system and sequentially modeling the error propagation through the involute gear stage, parallelogram input linkage, cycloid-pin gear mesh, and output coupling—while uniquely incorporating the critical feedback error from the output to the planetary carrier—a complete analytical framework has been constructed. The model quantitatively establishes the relationship between primitive component errors and the final output angular error.

The key findings, confirmed by numerical simulation of an RV-40E model and experimental spectral analysis, are:

- The output pin coupling mechanism’s manufacturing accuracy, specifically the position error (eccentricity) of the pin holes on the output plate, has the single largest direct impact on the transmission error of the rotary vector reducer.

- Errors originating in the precision cycloid-pin gear meshing stage, such as the cycloid tooth profile error, constitute the second most significant source of output inaccuracy, characterized by a multi-cyclical error signature.

- Errors in the first-stage involute planetary gears have a minimal effect on the final output due to the substantial attenuation provided by the large reduction ratio of the second stage.

- The feedback error arising from the rigid connection between the output plate and the planetary carrier, though small, is a systematic error component that must be considered in the design and error budgeting of high-precision rotary vector reducers.

This analysis provides a vital theoretical foundation for the precision design of rotary vector reducers. It guides manufacturers in allocating machining tolerances and inspection priorities: greatest emphasis should be placed on the accuracy of the output mechanism and the cycloid disc profile, followed by the crankpin eccentricity. The involute gear stage can have relatively relaxed tolerances without severely impacting the final output precision.

Future research directions should expand this model to include other significant error sources identified in experiments, such as:

- Cumulative position error of the crank pin holes on the cycloid disc.

- Pin gear radius errors and clearance.

- Systematic errors from the optimized modification (or “tooth flank correction”) of the cycloid profile for load distribution.

- Radial clearance in the crankshaft bearings and pin gear bearings.

- Thermal deformation errors under operational loads.

Integrating these factors into a stochastic error budget model will further enhance the predictive power and support the development of next-generation, ultra-high-precision rotary vector reducers for advanced robotics and automation.