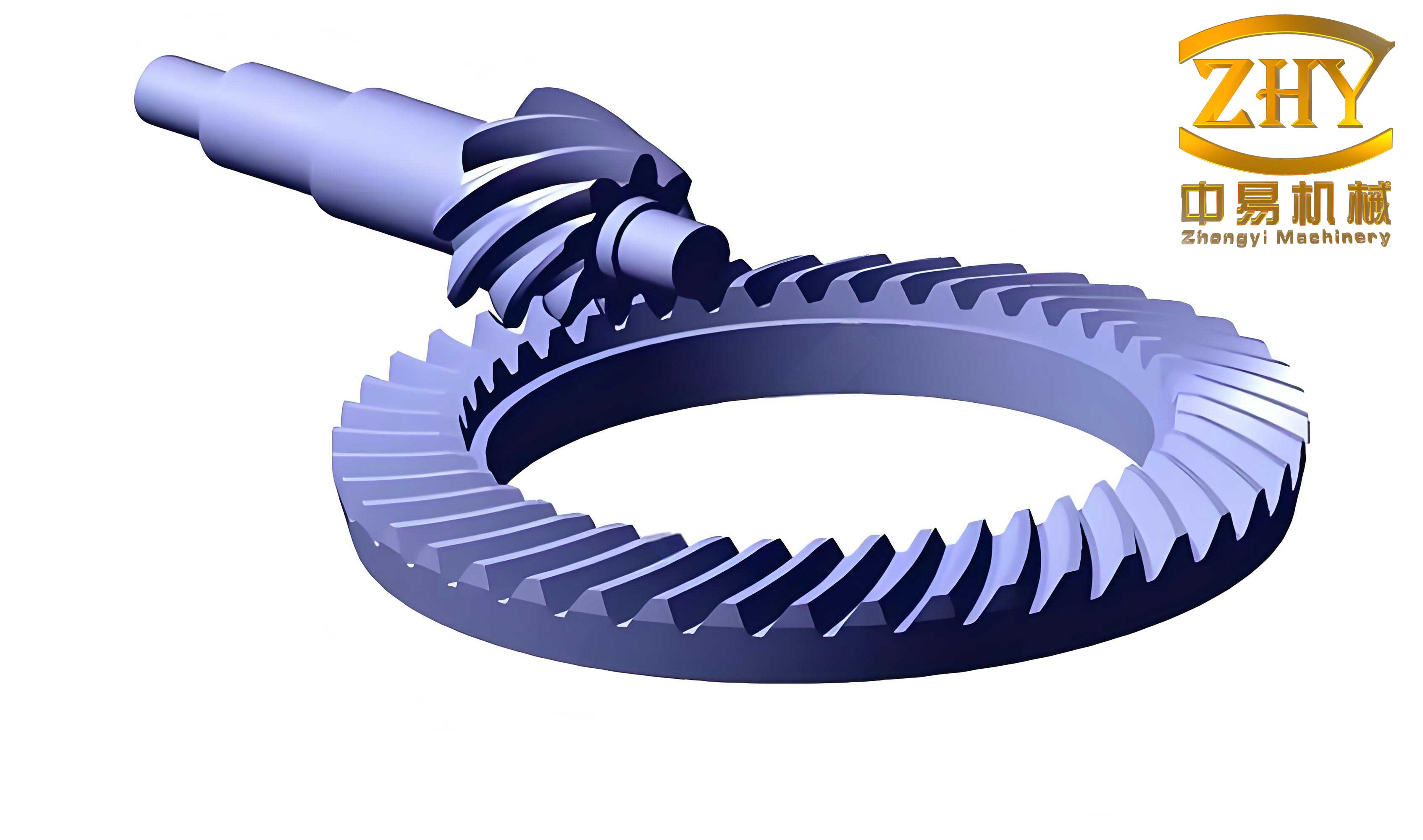

The pursuit of refined Noise, Vibration, and Harshness (NVH) characteristics in modern automotive drivetrains places significant emphasis on the dynamic behavior of final drive components. Among these, the hyperbolic gear set, also known as a hypoid gear set, is a critical element in rear and four-wheel-drive vehicle axles. Its design allows for a non-intersecting, offset axis configuration between the pinion and ring gear, enabling lower vehicle floors and improved driveline packaging. However, this geometric complexity also makes its meshing performance highly sensitive to positional inaccuracies introduced during assembly. The central parameter linking gear geometry, assembly quality, and NVH output is Transmission Error (TE). This article, from an engineering simulation perspective, delves into a comprehensive finite element analysis to investigate the influence of various assembly misalignments on the static and dynamic Transmission Error of a hyperbolic gear pair, aiming to quantify their relative impact and guide precision in manufacturing and assembly processes.

The performance of a hyperbolic gear is fundamentally governed by the conjugate contact between its intricately curved pinion and ring gear tooth surfaces. Transmission Error (TE) is defined as the deviation of the actual angular position of the driven gear from its theoretically perfect position, given a specific rotation of the driver gear. For a pinion-ring gear pair, it is mathematically expressed as:

$$ TE(\phi_1) = \left( \phi_2(\phi_1) – \phi_2^0 \right) – \frac{Z_1}{Z_2} \left( \phi_1 – \phi_1^0 \right) $$

where \( \phi_1 \) and \( \phi_2 \) are the rotational angles of the pinion and ring gear, respectively, \( \phi_1^0 \) and \( \phi_2^0 \) are their initial angles at the start of meshing, and \( Z_1 \) and \( Z_2 \) are the number of teeth. The magnitude of TE is typically in the order of arc-seconds (″). A low and smooth TE curve is a primary design target, as it minimizes vibratory excitations transmitted through the driveline, which manifest as gear whine. Even with optimally designed tooth geometry, this performance can be compromised by Assembly Errors (AEs), which displace the gears from their nominal theoretical positions. For a hyperbolic gear, four primary linear and angular assembly errors are defined relative to the ring gear’s coordinate system:

- Pinion Axis Error (\( \Delta P \)): Linear displacement of the pinion along its own axis. Positive denotes movement towards the ring gear.

- Ring Gear Axis Error (\( \Delta G \)): Linear displacement of the ring gear along its own axis. Positive denotes movement towards the pinion.

- Offset Error (\( \Delta E \)): Linear displacement of the pinion axis perpendicular to both gear axes, effectively changing the nominal hypoid offset. Positive denotes the pinion moving downwards (in a typical driveline view).

- Shaft Angle Error (\( \Delta \Sigma \)): Angular error in the non-parallel, non-intersecting shaft angle. Positive denotes an increase in the nominal shaft angle.

These misalignments alter the local contact conditions, pressure angles, and effective lead and profile curvatures, thereby modifying the loaded tooth deflection and the resultant TE. Isolating and understanding the effect of each error is crucial for setting appropriate assembly tolerances.

Finite Element Modeling Methodology for Hyperbolic Gear Analysis

To accurately capture the nonlinear contact mechanics, elastic deformations, and friction in a loaded hyperbolic gear pair, a three-dimensional Finite Element Model (FEM) was developed. This approach supersedes traditional unloaded Tooth Contact Analysis (TCA) by simulating real operating conditions. The model was constructed for a passenger SUV rear axle gear set. The geometry of the pinion and ring gear, including detailed tooth modifications (ease-off), was imported. A critical step was the meshing strategy. The regions of highest interest—the tooth flanks and fillets—require a fine mesh to resolve contact pressures and bending stresses accurately. Conversely, the gear body regions can use a coarser mesh to reduce computational cost without sacrificing result fidelity for TE calculation. A structured hexahedral mesh was predominantly used for its numerical stability. The final mesh comprised approximately 83,000 elements for the pinion and 293,000 elements for the ring gear. The material was defined as case-hardened steel (20CrMnTi) with standard properties: Young’s Modulus \( E = 212 \) GPa, Poisson’s ratio \( \nu = 0.3 \), and density \( \rho = 7900 \) kg/m³.

The boundary conditions and loads were applied to simulate a quasi-static meshing cycle. A reference point was created at the center of each gear’s axis and coupled kinematically to all nodes on the respective bore surface, creating a rigid connection. This allows the application of rotation and torque via the reference point. The pinion reference point was prescribed a finite rotation to mesh through several tooth engagements. The ring gear reference point was restrained in all translational and rotational degrees of freedom except for rotation about its axis, where a constant resistive torque of 100 N·m was applied to simulate the vehicle load. The tooth contact interaction was defined with a “hard” normal contact property and a tangential friction behavior with a coefficient of \( \mu = 0.1 \). To ensure smooth engagement and numerical convergence, the rotation was applied using a smooth step amplitude function, initially removing backlash before applying the full motion. Analyses were run in both static/implicit and dynamic/explicit procedures within the Abaqus solver to compare results. The key output was the time-history (or rotation-history) of the angular positions \( \phi_1 \) and \( \phi_2 \), from which the TE was calculated using the formula above.

| Model Aspect | Specification |

|---|---|

| Element Type | Hexahedral (C3D8R) |

| Pinion Element Count | ~83,000 |

| Ring Gear Element Count | ~293,000 |

| Tooth Surface Mesh Size | ~0.5 mm |

| Material | 20CrMnTi Steel |

| Young’s Modulus (E) | 212 GPa |

| Poisson’s Ratio (ν) | 0.3 |

| Friction Coefficient (μ) | 0.1 |

| Applied Ring Gear Torque | 100 N·m |

| Analysis Types | Static (Implicit) & Dynamic (Explicit) |

Transmission Error Characteristic: Static vs. Dynamic Response

Before introducing assembly errors, it is essential to understand the baseline TE characteristic of the perfectly aligned hyperbolic gear. The static analysis, which neglects inertial effects, provides the TE curve purely due to geometric mismatch and elastic deflection under load. For one mesh cycle, the static TE typically presents a parabolic-like, periodic waveform. Each peak corresponds to a new tooth pair coming into contact, and the curve’s shape is a direct consequence of the designed ease-off and load distribution.

The dynamic analysis incorporates mass and damping properties, simulating the transient response as the gears start from rest and reach a steady rotational speed. The comparison reveals a critical insight:

$$ TE_{dynamic}(t) = TE_{static}(\phi_1) + \delta_{inertial}(t) $$

where \( \delta_{inertial}(t) \) is an oscillatory component decaying over time. The dynamic TE curve exhibits significant oscillation during the initial engagement due to contact impact. However, as the rotational speed stabilizes, the inertial oscillations damp out, and the dynamic TE converges precisely onto the static TE curve. The time (or rotational distance) required for stabilization increases with the prescribed pinion speed. This convergence demonstrates that for studying the inherent meshing excitation governed by tooth geometry and deflection—which is the primary source of gear whine—the static TE is a valid and efficient metric. Therefore, the subsequent investigation into the effects of assembly misalignments focuses on the static Transmission Error, as it represents the steady-state forcing function.

Systematic Evaluation of Assembly Error Impacts on Hyperbolic Gear TE

The core of this investigation involves varying each of the four assembly errors independently within a realistic tolerance range, typically ±0.3 mm for linear errors and ±0.3° for the angular error, and observing the resultant change in the static TE curve. The analysis not only tracks changes in the peak-to-peak amplitude of TE but also observes shifts in its mean value and phase.

1. Influence of Pinion Axis Error (\( \Delta P \))

Varying \( \Delta P \) simulates the pinion being installed too deep or too shallow into the differential housing. The results show a pronounced effect. As \( \Delta P \) increases (pinion moves towards the ring gear), the entire TE curve shifts vertically upward in the TE-angle plot. This vertical shift indicates a change in the mean angular lag of the ring gear. More importantly, when the curves are normalized to a zero mean for comparison, a clear lateral translation along the meshing phase (pinion rotation axis) is observed. The direction and magnitude of this translation affect the TE amplitude. The sensitivity is asymmetric: a negative \( \Delta P \) (pinion retracted) causes a more significant increase in TE amplitude compared to a positive \( \Delta P \) of the same magnitude. This asymmetry stems from the changing contact pattern location relative to the tooth edges.

2. Influence of Ring Gear Axis Error (\( \Delta G \))

The ring gear axial position error \( \Delta G \) also causes a vertical shift in the TE curve. However, its impact on the normalized TE amplitude is minimal. When the curves are aligned to the same mean, they nearly superimpose, indicating that the shape and peak-to-peak value of the TE function are largely invariant to small axial movements of the ring gear. This suggests that the ring gear’s axial location is a less critical tolerance from a pure TE excitation perspective for this specific hyperbolic gear design.

3. Influence of Offset Error (\( \Delta E \))

The hypoid offset error \( \Delta E \) alters the fundamental relative positioning of the axes. Similar to other errors, it induces a vertical shift in the raw TE output. The normalized TE analysis reveals a distinct behavior. The TE curve translates laterally, and its amplitude is significantly affected in an asymmetric manner, but opposite to the pinion axis error. A positive \( \Delta E \) (increased offset, pinion lowered) leads to a substantial increase in TE amplitude. Conversely, a negative \( \Delta E \) (decreased offset) results in a much smaller change in amplitude. This highlights the non-linear and directional sensitivity of the meshing action to the core hypoid geometry parameter.

4. Influence of Shaft Angle Error (\( \Delta \Sigma \))

The shaft angle error \( \Delta \Sigma \) proves to be the most influential parameter. It causes a vertical shift in the TE curve, but the effect on the normalized TE amplitude is dominant and symmetric. Any deviation from the nominal shaft angle—whether positive or negative—causes a significant and roughly equal increase in the peak-to-peak Transmission Error. The TE curve undergoes a lateral translation, and its waveform distorts, increasing the magnitude of fluctuation. This strong sensitivity is due to the shaft angle being a primary determinant of the local tooth surface conformity; even a small angular misalignment severely degrades the conjugate contact condition across the entire tooth flank of the hyperbolic gear.

Quantitative Comparison and Sensitivity Ranking

To distill the findings, the change in TE amplitude (\( \Delta TE_{amp} \)) relative to the perfectly aligned baseline was calculated for each assembly error at the extremes of the studied range. This allows for a direct comparison of their impact. The sensitivity can be summarized by a simplified linearized model for small errors:

$$ \Delta TE_{amp} \approx \left| \frac{\partial TE_{amp}}{\partial \epsilon} \right| \cdot \Delta \epsilon $$

where \( \epsilon \) represents any of the four assembly errors. The partial derivative represents the sensitivity coefficient. The analysis allows us to rank these coefficients.

| Assembly Error (Symbol) | Primary Effect on TE Curve | Impact on TE Amplitude | Directional Sensitivity | Relative Influence Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaft Angle Error (\( \Delta \Sigma \)) | Vertical shift, major lateral translation & distortion | Very High Increase (Symmetric) | Low (Equal for ±) | 1 (Most Critical) |

| Pinion Axis Error (\( \Delta P \)) | Vertical shift, lateral translation | High Increase (Asymmetric) | High (Larger for -ΔP) | 2 |

| Offset Error (\( \Delta E \)) | Vertical shift, lateral translation | Moderate Increase (Asymmetric) | High (Larger for +ΔE) | 3 |

| Ring Gear Axis Error (\( \Delta G \)) | Vertical shift | Negligible Change | Very Low | 4 (Least Critical) |

The ranking is unequivocal: Shaft Angle Error (\( \Delta \Sigma \)) is the most critical, followed by Pinion Axis Error (\( \Delta P \)). Both \( \Delta P \) and \( \Delta E \) exhibit strong directional asymmetry, meaning the sign of the error matters greatly. This has direct implications for assembly process control and potential compensatory adjustments during final assembly or shimming of the hyperbolic gear set.

Conclusions and Engineering Implications

This detailed finite element investigation into the effects of assembly misalignments on hyperbolic gear Transmission Error yields several definitive conclusions with practical significance for automotive driveline engineering:

- Static TE as a Design Metric: For the purpose of evaluating gear geometry and assembly-induced excitations, static nonlinear finite element analysis provides an efficient and accurate representation of the steady-state Transmission Error. Dynamic analysis is crucial for studying transient phenomena like launch shudder or impact noise but converges to the static TE result for stable, continuous meshing.

- Global Shift vs. Local Change: Assembly errors primarily cause a global vertical shift (change in mean value) of the TE curve, which may affect gear backlash but is often compensated by system compliance. The more critical effect is the lateral translation and change in the amplitude of the TE curve, which directly alters the vibratory excitation force.

- Hierarchical Sensitivity: The sensitivity of TE amplitude to the four classic assembly errors follows a clear hierarchy: Shaft Angle Error (\( \Delta \Sigma \)) >> Pinion Axis Error (\( \Delta P \)) > Offset Error (\( \Delta E \)) >> Ring Gear Axis Error (\( \Delta G \)). This ranking provides clear guidance for allocating tighter tolerances and more rigorous inspection procedures during the manufacturing and assembly of the hyperbolic gear housing and differential carrier.

- Directional Asymmetry: The effects of pinion axial and offset errors are not symmetric. Retracting the pinion or increasing the hypoid offset tends to degrade TE performance more severely than the opposite direction of error. This knowledge can be used for implementing directional tolerance schemes or for selective assembly to minimize the final TE.

The primary engineering directive is that controlling the shaft angle between the pinion and ring gear is paramount for achieving low gear noise. Precision in machining the differential housing bore and the pinion bearing bores in the axle assembly is non-negotiable. Furthermore, the significant impact of pinion axial location underscores the importance of accurate pinion depth setting via selective shims or crush sleeves.

Future research directions include investigating the combined effects of multiple, simultaneous assembly errors, which is the real-world scenario. A robust statistical or Six-Sigma analysis could predict TE distributions based on the individual error tolerances. Additionally, establishing a direct transfer path from the quantified TE amplitudes, as modified by assembly errors, to the actual sound pressure level measured at the vehicle driver’s ear would provide a complete NVH chain of causality. Finally, exploring active or passive compensatory techniques, such as gear tooth micro-geometry modifications optimized for a slightly misaligned condition, could enhance the robustness of hyperbolic gear designs against inevitable assembly variations.