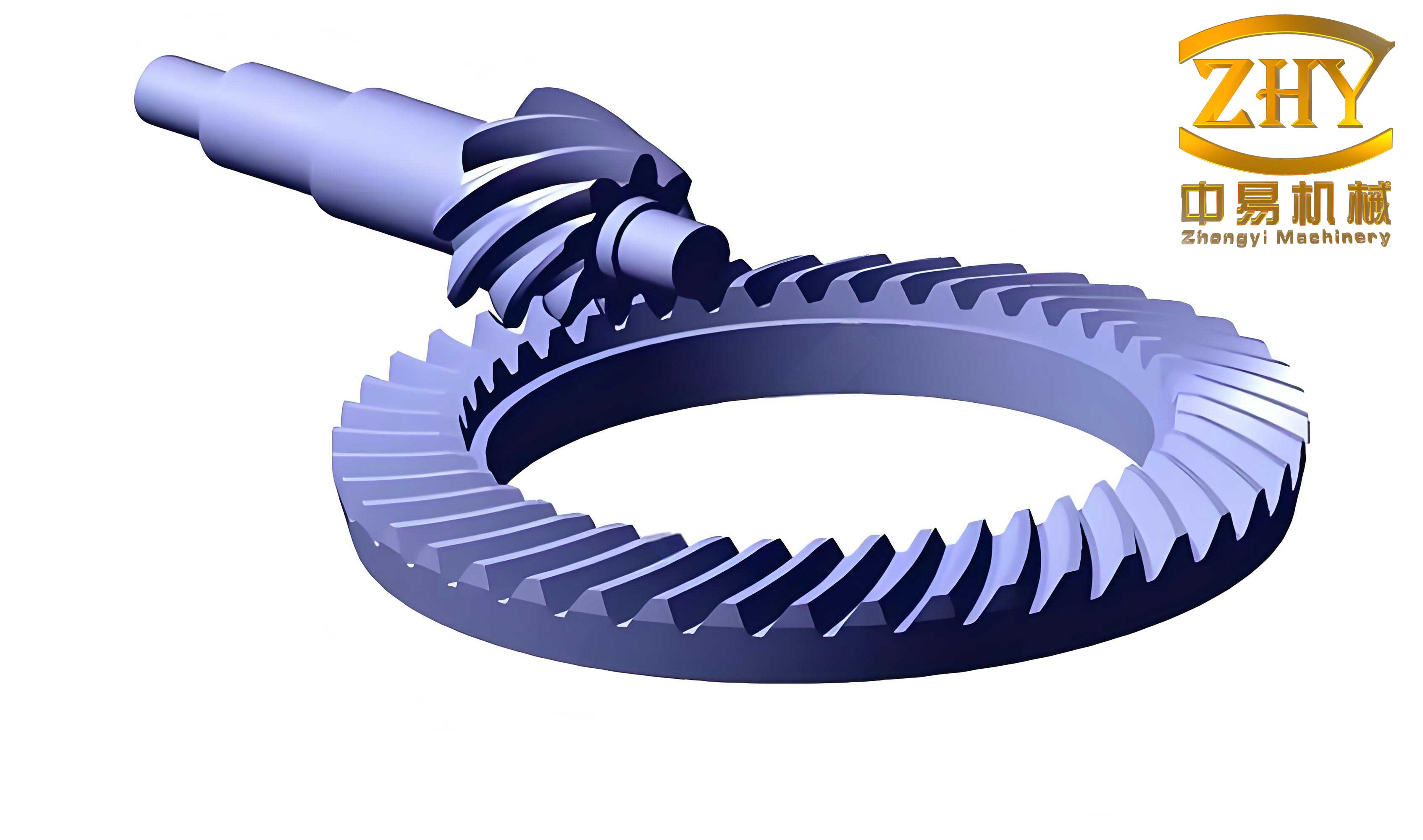

In the realm of heavy-duty automotive powertrains, the drive axle stands as a critical subsystem, and at its heart lies the hyperbolic gear pair—specifically, the hypoid gear set. This gear type, characterized by its offset axes and curved teeth, is favored for its ability to provide high torque transmission, smooth operation, and a compact design. However, its operational reality is far from the idealized conditions of a test bench. In practical applications, particularly under high-torque and high-speed conditions, the entire drive axle system—comprising gears, shafts, bearings, and the housing—undergoes significant elastic deformation. This system-wide deformation induces misalignment at the gear mesh, drastically altering the contact pattern on the tooth flanks. The consequence is often a severe bias in load distribution, leading to localized high stress, increased friction, elevated temperatures, accelerated wear, and ultimately, a reduction in the overall transmission efficiency and service life of the axle. Therefore, accurately predicting the meshing performance, especially efficiency, necessitates a methodology that moves beyond analyzing the gear pair in isolation. We must develop a comprehensive model that integrates the system’s mechanical response under load with a detailed analysis of the tooth contact under mixed lubrication conditions. This article presents our developed framework for calculating the meshing efficiency of drive axle hyperbolic gears, explicitly accounting for the deformation of the surrounding system. Our approach synergizes a multi-support shaft system model for misalignment prediction, a friction-loaded tooth contact analysis (FLTCA) for precise load distribution, and a mixed-elastohydrodynamic lubrication (mixed-EHL) model for friction calculation, culminating in a validated method for efficiency prediction.

The foundation of our analysis is the accurate prediction of how the drive axle system deforms under operational loads. We model the complete system—including the pinion shaft, differential casing, ring gear, and all supporting bearings—as a coupled multi-support shaft system. The core of this model is a global stiffness matrix K assembled from the stiffness contributions of each component (shaft segments, bearings modeled with nonlinear stiffness, and the housing approximated with beam/shell elements). The system equilibrium under an applied load vector F (comprising input torque and reaction forces) is governed by the linear equation:

$$ \mathbf{K} \cdot \boldsymbol{\delta} = \mathbf{F} $$

where $\boldsymbol{\delta}$ is the vector of nodal displacements and rotations. Solving this system yields the displacement at any node, specifically at the centers of the pinion and ring gear. The relative misalignment between the two gears is not a simple subtraction of these displacements but must be projected onto the critical directions defining the gear mesh. Defining coordinate systems attached to each gear, the misalignment components are calculated as follows. For the pinion (denoted by subscript $p$) with center displacement $(\delta_{px}, \delta_{py}, \delta_{pz})$ and rotations $(\theta_{px}, \theta_{py}, \theta_{pz})$, and for the ring gear (denoted by subscript $g$) with $(\delta_{gx}, \delta_{gy}, \delta_{gz})$ and $(\theta_{gx}, \theta_{gy}, \theta_{gz})$, the individual misalignments are:

Pinion Misalignment:

$$\begin{aligned}

\Delta P_1 &= \delta_{px}, \\

\Delta W_1 &= -\delta_{py} + W_P \cos \alpha \sin \theta_{pz}, \\

\Delta Y_1 &= -\delta_{pz} – W_P \cos \alpha \sin \theta_{py}, \\

\Delta \Sigma_1 &= -\theta_{pz}.

\end{aligned}$$

Ring Gear Misalignment:

$$\begin{aligned}

\Delta P_2 &= -\delta_{gx} – G_P \cos \beta \sin \theta_{gz}, \\

\Delta W_2 &= \delta_{gy}, \\

\Delta Y_2 &= \delta_{gz} – G_P \cos \beta \sin \delta_{gx}, \\

\Delta \Sigma_2 &= \theta_{gz}.

\end{aligned}$$

Here, $\Delta P_i$, $\Delta W_i$, $\Delta Y_i$, and $\Delta \Sigma_i$ represent displacements along the pinion axis, wheel axis, offset direction, and an angular displacement about the shaft angle, respectively. $W_P$ and $G_P$ are distances from the mesh point to the respective gear centers, and $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are the offset angles. The total gear mesh misalignment vector $\mathbf{E}$ used in the subsequent contact analysis is the sum of the respective components from both gears:

$$ \mathbf{E} = [\Delta P, \Delta W, \Delta Y, \Delta \Sigma]^T = [\Delta P_1+\Delta P_2, \ \Delta W_1+\Delta W_2, \ \Delta Y_1+\Delta Y_2, \ \Delta \Sigma_1+\Delta \Sigma_2]^T. $$

This misalignment vector $\mathbf{E}$ is a function of the applied load and is a crucial input that couples the system-level analysis with the gear-pair-level analysis.

The accurate geometrical definition of the tooth flanks is paramount. For face-hobbed hyperbolic gears, the tooth surface is a complex sculpted entity generated by the relative motion between the cutting tool and the gear blank. We simulate this manufacturing process mathematically. The coordinates of a point on the cutter blade $\mathbf{r}_c$ are transformed through a series of coordinate systems representing the machine tool settings (cutter tilt, swivel, radial setting, workpiece offset, etc.) to the final gear coordinate system $\mathbf{r}_g$. This transformation is a function of the machine settings $\boldsymbol{\xi}$ and the motion parameters of the process (cutter rotation $\theta_d$, work rotation $\phi_d$):

$$ \mathbf{r}_g = \mathbf{T}(\theta_d, \phi_d, \boldsymbol{\xi}) \cdot \mathbf{r}_c. $$

$$ \mathbf{n}_g = \mathbf{R}(\theta_d, \phi_d, \boldsymbol{\xi}) \cdot \mathbf{n}_c. $$

where $\mathbf{n}_g$ is the surface unit normal. By discretizing the motion parameters, we obtain a point cloud representing the pinion and gear tooth surfaces. These points are then interpolated using Ferguson patches or NURBS surfaces to create continuous, differentiable geometric models for both the convex and concave flanks of each gear. This digital twin of the physical gear pair forms the basis for all contact simulations.

Under high load and moderate speed, the lubricant film in a hyperbolic gear contact is often too thin to fully separate the surfaces, leading to a mixed lubrication regime where load is carried partly by hydrodynamic pressure in the lubricant film and partly by asperity contact. The friction coefficient $\mu_{ML}$ in this regime is modeled as a weighted average of the boundary friction coefficient $\mu_{DC}$ and the fluid friction coefficient $\mu_{FL}$, with the weight being the load-sharing factor $f_K$:

$$ \mu_{ML} = \mu_{FL} \cdot f_K^{1.2} + \mu_{DC} \cdot (1 – f_K). $$

The load-sharing factor $f_K$ depends on the film thickness ratio $\lambda$, defined as the ratio of the central EHL film thickness $h_0$ to the composite surface roughness $S$:

$$ f_K = \frac{1.21 \lambda^{0.64}}{1 + 0.37 \lambda^{1.26}}, \quad \lambda = \frac{h_0}{S}, \quad S = \sqrt{S_{q1}^2 + S_{q2}^2}. $$

The central film thickness $h_0$ is calculated using a widely accepted regression formula based on dimensionless parameters:

$$ h_0 = 2.69 \cdot R_x \cdot W^{-0.067} \cdot U^{0.67} \cdot G^{0.53} \cdot (1 – 0.61 e^{-0.73 \kappa}). $$

The dimensionless parameters are defined as:

$$ W = \frac{F_m}{E_{eq} R_x^2}, \quad U = \frac{\eta_0 V_e}{E_{eq} R_x}, \quad G = \alpha E_{eq}, \quad \kappa = 1.03 \left( \frac{R_x}{R_y} \right)^{0.64}. $$

Here, $F_m$ is the normal load per unit width, $E_{eq}$ is the equivalent Young’s modulus, $R_x$ and $R_y$ are the effective radii of curvature in the principal directions, $\eta_0$ is the dynamic viscosity at ambient pressure, $\alpha$ is the pressure-viscosity coefficient, and $V_e$ is the entrainment velocity ($V_e = (V_1 + V_2)/2$, where $V_1$ and $V_2$ are the surface velocities at the contact). The fluid friction coefficient $\mu_{FL}$ is itself determined by a complex regression model dependent on slide-to-roll ratio $SR$, Hertzian pressure $p_h$, and other parameters:

$$ \mu_{FL} = e^{f(SR, p_h, \eta_0, S)} \cdot (p_h / \text{MPa})^{b_2} \cdot |SR|^{b_3} \cdot (V_e / \text{m·s}^{-1})^{b_6} \cdot \eta_0^{b_7} \cdot R_x^{b_8}, $$

$$ f(\cdot) = b_1 + b_4 |SR| (p_h / \text{MPa}) \log(\eta_0 / \text{Pa·s}) + b_5 e^{-|SR| (p_h / \text{MPa}) \log(\eta_0 / \text{Pa·s})} + b_9 e^{S}. $$

The regression coefficients $b_1$ through $b_9$ are obtained from extensive EHL experiments. A typical set of values is presented in Table 1.

| Coefficient | Value | Coefficient | Value | Coefficient | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $b_1$ | -8.916465 | $b_4$ | -0.354068 | $b_7$ | 0.752755 |

| $b_2$ | 1.03303 | $b_5$ | 2.812084 | $b_8$ | -0.390958 |

| $b_3$ | 1.036077 | $b_6$ | -0.100601 | $b_9$ | 0.620305 |

Table 1: Typical regression coefficients for the fluid friction model.

Our core computational engine is the Frictional Loaded Tooth Contact Analysis (FLTCA) algorithm. It is an iterative numerical procedure that solves for the contact pressure distribution and subsurface stresses on the deformed tooth flanks, given the system misalignment and applied torque. The flowchart of this integrated process is as follows, and each step is detailed below:

- System Analysis: For a given input torque $T_{in}$, solve the multi-support shaft system model (Eq. 1) to obtain the bearing reactions and the gear misalignment vector $\mathbf{E}$.

- Unloaded Transmission Error (UTE) / TCA: Perform unloaded tooth contact analysis to find the initial contact path and transmission error under the prescribed misalignment $\mathbf{E}$, ignoring tooth compliance.

- Load Application & Deformation Calculation: Discretize the potential contact area into a grid of points. Apply an initial guess for the contact pressure distribution $\mathbf{p}$. For each loaded point, calculate the total deformation $\boldsymbol{\delta}_{total}$, which is the sum of:

- Bending and Shear Deflection $\boldsymbol{\delta}_{bs}$: Calculated using a finite element model of the gear body or influence coefficient matrices derived from such a model.

- Local Contact Deformation $\boldsymbol{\delta}_c$: Calculated using Boussinesq’s half-space theory or a detailed approximation like the “Winklerv” foundation model. The deformation at point $i$ due to pressure at point $j$ is $\delta_{c,i} = \sum_j C_{ij} p_j$, where $C_{ij}$ is the compliance influence coefficient.

- Global Rigid Body Approach $\boldsymbol{\delta}_r$: Represented by a scalar separation $Z$ along the line of action.

- Compatibility Equation: Enforce the condition that for points in contact, the total deformation must equal the initial geometrical gap $d_0$ (from UTE), closing it. For points not in contact, the pressure must be zero.

$$ \delta_{bs} + \delta_c – (Z – d_0) = 0 \quad \text{(for contact points)}. $$

This is solved iteratively, often using a conjugate gradient method, to find the pressure distribution $\mathbf{p}$ that satisfies compatibility. - Equilibrium Equation: Ensure the integrated contact pressure balances the applied normal load $W_n$ derived from the input torque.

$$ \sum_{i \in \text{contact}} p_i \cdot A_i = W_n. $$

This is achieved by adjusting the rigid body approach $Z$. - Friction Integration: Once the pressure distribution is known, calculate the local friction force $f_i = \mu_{ML,i} \cdot p_i \cdot A_i$, where $\mu_{ML,i}$ is computed using the mixed lubrication model (Eq. 8-16) based on local kinematics (sliding velocity $V_{s,i}$, entrainment velocity $V_{e,i}$) and pressure $p_i$.

- Convergence Check: Iterate steps 3-6 until both the pressure distribution and the rigid body approach $Z$ converge within specified tolerances ($\epsilon_1$, $\epsilon_2$).

The primary output of the FLTCA for a given meshing position (pinion roll angle $\phi_p$) is the detailed contact pattern (size, shape, location), the distribution of contact pressure $p(x,y)$, and the corresponding distribution of friction coefficient $\mu(x,y)$ and friction force $f(x,y)$.

The instantaneous power loss $P_{inst}$ at a given meshing position is the sum of the frictional power dissipation at all discrete contact cells $i$ across all contacting tooth pairs $k$:

$$ P_{inst}(\phi_p) = \sum_{k=1}^{m} \sum_{i=1}^{n_k} f_{k,i} \cdot V_{s,k,i} = \sum_{k=1}^{m} \sum_{i=1}^{n_k} \mu_{ML,k,i} \cdot p_{k,i} \cdot A_{k,i} \cdot V_{s,k,i}. $$

where $m$ is the number of simultaneous tooth pairs in contact (typically 1 or 2 for hyperbolic gears), $n_k$ is the number of contact cells on the $k$-th pair, $V_{s,k,i}$ is the local sliding velocity vector whose magnitude is the scalar sliding speed, and $A_{k,i}$ is the area of the contact cell. The total average frictional power loss $P_{g,fric}$ over one complete meshing cycle (from pinion roll angle $\theta_1$ to $\theta_2$) is then:

$$ P_{g,fric} = \frac{1}{\theta_2 – \theta_1} \int_{\theta_1}^{\theta_2} P_{inst}(\phi_p) \, d\phi_p. $$

Finally, the meshing efficiency $\eta_{g,fric}$ of the hyperbolic gear pair itself is defined as the ratio of the output power to the sum of the output power and the gear frictional loss:

$$ \eta_{g,fric} = \frac{P_{out}}{P_{out} + P_{g,fric}} = \frac{|T_{out}| \omega_{out}}{|T_{out}| \omega_{out} + P_{g,fric}}. $$

It is crucial to distinguish this from the overall drive axle efficiency, which includes bearing losses ($P_{b,fric}$) and spin-dependent churning/windage losses ($P_{drag}$). In a typical test bench setup where input speed and output torque are controlled, the overall axle efficiency $\eta_{axle}$ is measured. The gear meshing efficiency can be extracted if the other losses are known or estimated: $ \eta_{g,fric} \approx \eta_{axle} – \eta_{drag} + \frac{P_{b,fric}}{P_{in}} $, where $\eta_{drag}$ is the no-load efficiency.

To validate our integrated methodology, we conducted extensive experiments on a full-scale drive axle test bench. The test setup controls input speed and applies a braking torque at the output hubs, simulating road load. We performed two main types of validation tests: loaded contact pattern checks and system efficiency measurements. The basic geometric and manufacturing parameters of the test hypoid gear set are summarized in Tables 2 through 5.

| Basic Gear Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Number of teeth (Pinion/Gear) | 10 / 39 |

| Shaft angle | 90° |

| Mean pressure angle | 22.5° |

| Offset | 30 mm |

| Face width (Pinion/Gear) | 55.8 mm / 50.5 mm |

| Mean spiral angle (Pinion/Gear) | 44° / 30.8° |

| Hand of spiral (Pinion/Gear) | LH / RH |

Table 2: Fundamental parameters of the test hyperbolic gear set.

| Bearing | Inner Dia. (mm) | Outer Dia. (mm) | Width (mm) | Contact Angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinion Front | 50.00 | 105.00 | 34.50 | 30.00° |

| Pinion Rear | 60.00 | 130.00 | 43.00 | 30.00° |

| Differential Left | 85.00 | 130.00 | 29.00 | 16.42° |

| Differential Right | 70.00 | 110.00 | 25.00 | 16.17° |

Table 3: Bearing specifications within the test drive axle.

Contact Pattern Validation: The axle housing was partially removed to observe the gear mesh. The contact pattern under various loads was recorded using a high-temperature grease. First, the no-load pattern was checked against the TCA prediction to validate the basic gear geometry and alignment setup. Excellent agreement was found for both drive (forward) and coast (reverse) sides. Next, loaded patterns were compared. A critical finding was the significant effect of system deformation. For instance, under full drive torque, the predicted contact pattern without considering system misalignment showed a centered, benign contact. However, the FLTCA prediction incorporating the calculated misalignment $\mathbf{E}$ revealed a pronounced shift of the contact towards the toe and the outer edge (for the drive side), which matched the experimental observation almost exactly. This shift is due to the combined effect of pinion deflection and housing deformation, which rotates and translates the pinion relative to the gear. A similar agreement was found for the coast side under high load. This validation confirmed that our multi-support shaft system model successfully predicts the operative misalignment and that our FLTCA can accurately compute the resulting loaded contact pattern for the hyperbolic gear.

Meshing Efficiency Validation: Efficiency tests were conducted over a matrix of operating conditions: vehicle speed equivalents from 10 to 80 km/h and load powers from 10 to 100 kW. The axle was soaked to a stabilized oil temperature of $(80 \pm 5)^\circ$C. The overall axle input power $P_{in}$ was measured for each speed/load combination. The no-load input power $P_{drag}$ (churning + bearing spin losses) was measured separately at each speed with zero output torque. Bearing frictional losses $P_{b,fric}$ were estimated using established empirical models (e.g., the SKF model) based on the measured bearing loads from our system analysis and their operating speeds. The gear meshing power loss $P_{g,fric}$ was then derived from Eq. 22, and subsequently the gear meshing efficiency $\eta_{g,fric}$.

Table 4 shows a comparison between calculated and experimentally derived gear meshing efficiencies for a subset of operating conditions.

| Condition (Speed / Load) | Calc. $\eta_{g,fric}$ (%) | Exp. $\eta_{g,fric}$ (%) | Absolute Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 km/h / 20 kW | 98.65 | 98.71 | -0.06 |

| 40 km/h / 40 kW | 98.92 | 98.87 | +0.05 |

| 60 km/h / 60 kW | 99.12 | 99.08 | +0.04 |

| 80 km/h / 80 kW | 99.25 | 99.20 | +0.05 |

| 60 km/h / 100 kW | 99.05 | 98.99 | +0.06 |

Table 4: Comparison of calculated versus experimental gear meshing efficiency.

The results show a very strong correlation, with discrepancies typically within $\pm 0.1\%$, which is within the bounds of experimental uncertainty. The analysis of trends reveals important insights. At constant load power (e.g., 80 kW), efficiency increases non-linearly with speed, rising by about 1% from 10 to 80 km/h. This is attributed to the formation of a more robust lubricant film ($h_0$ increases, see Eq. 12), which raises the $\lambda$ ratio, increases the load-sharing factor $f_K$, and consequently reduces the mixed friction coefficient $\mu_{ML}$ (Eq. 8). At constant speed (e.g., 60 km/h), the efficiency shows a slight, non-monotonic variation with load. Initially, efficiency may dip slightly as load increases due to a thinning film (lower $\lambda$) and higher asperity contact. However, at very high loads, the associated increase in system misalignment $\mathbf{E}$ can alter the contact kinematics and pressure distribution in a way that sometimes slightly moderates the friction losses. Crucially, calculations that ignored system deformation showed a consistent over-prediction of efficiency, especially at high loads and high speeds, by up to 0.3-0.4%. This systematic error underscores the necessity of including the system compliance model for accurate hyperbolic gear efficiency prediction in real-world applications.

This work presents a holistic and validated methodology for predicting the meshing efficiency of drive axle hyperbolic gears under realistic operating conditions. The key innovation is the tight coupling of a system-level deformation analysis with a high-fidelity, mixed-lubrication FLTCA for the gear pair. We have demonstrated that the elastic deformations of the shaft-bearing-housing system induce a misalignment at the gear mesh that significantly alters the loaded contact pattern and pressure distribution. Ignoring this effect leads to incorrect predictions of both gear durability and efficiency.

Our method proceeds in a logically connected sequence: (1) The multi-support shaft system model computes load-dependent gear misalignment. (2) The precise tooth geometry, derived from machine-tool settings, is used to establish unloaded contact. (3) The FLTCA solver, incorporating tooth bending, contact deformation, and a mixed-EHL friction model, computes the detailed pressure and friction distribution under load and misalignment. (4) The instantaneous and average frictional power loss and meshing efficiency are then calculated by integrating over the contact areas and the meshing cycle.

Experimental validation on a full axle test rig confirmed the accuracy of the predicted loaded contact patterns and the meshing efficiency across a wide range of speeds and loads. The agreement between calculation and experiment was excellent, with efficiency errors within a tenth of a percent. The results clearly show that system deformation is not a secondary effect but a primary driver of the operational state of a hyperbolic gear set in a drive axle. The methodology provides design engineers with a powerful virtual prototyping tool. It enables the optimization of not only the gear macro/micro-geometry for low noise and high strength but also the system stiffness layout (bearing positions, housing ribs, shaft diameters) to control misalignment and, consequently, to maximize transmission efficiency and reliability. Future work will focus on integrating thermal models to account for heat generation from friction and its feedback on lubricant properties, bearing clearances, and further system deformation, creating an even more comprehensive virtual testing environment for advanced hyperbolic gear drive axles.