In the field of automotive drivetrains, hypoid gears are pivotal components due to their smooth transmission, high strength, and superior spatial arrangement compared to conventional spiral bevel gears. These gears are extensively used in rear axle drives, particularly in heavy-duty vehicles. The manufacturing process often involves gear cutting followed by lapping as a final finishing operation. Lapping is preferred over grinding because it preserves the hardened surface layer post-heat treatment, which is crucial for gear durability, and it is more efficient, typically taking only 4–6 minutes per gear pair. However, during lapping, a phenomenon known as “lapping burn” can occur, leading to surface defects that may cause pitting, spalling, or even tooth breakage during service. This article, from my perspective as a researcher in gear technology, delves into the characteristics, impacts, mechanisms, and suppression methods of lapping burn in hypoid gears. I will explore this issue through detailed analysis, mathematical modeling, experimental validation, and practical insights, emphasizing the keyword “hypoid gears” throughout.

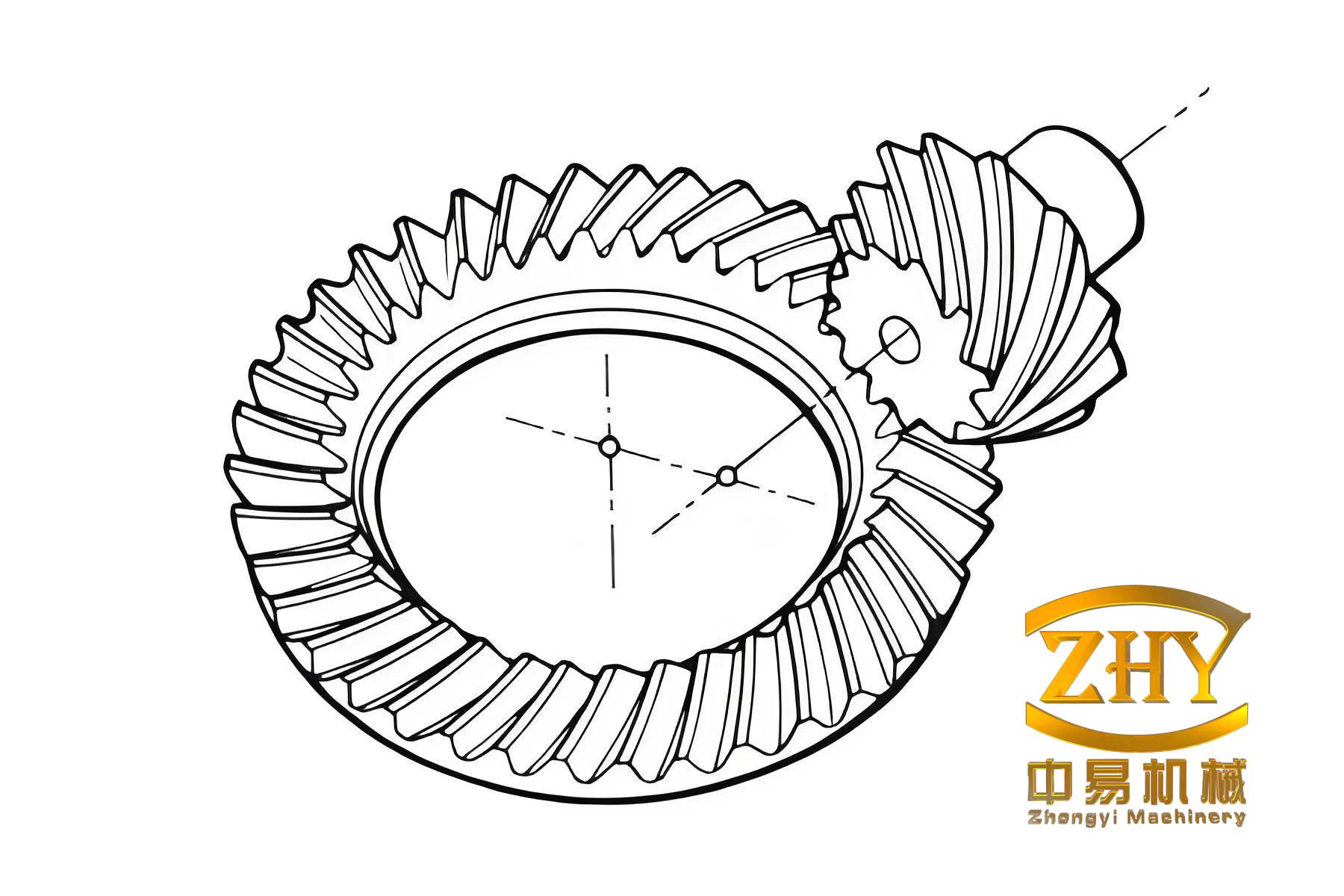

Hypoid gears are a type of spiral bevel gear with non-intersecting axes, allowing for offset placement that enhances torque capacity and design flexibility. The lapping process involves running the gear pair under light load with an abrasive compound to correct minor tooth form errors, improve surface finish, and optimize contact pattern. Despite its benefits, lapping can induce thermal damage on the tooth surface, akin to grinding burn, but with less obvious macroscopic features. This burn is often overlooked, yet it significantly compromises the lifespan of hypoid gears. In this work, I aim to provide a comprehensive study on lapping burn, starting with its identification and progressing to root-cause analysis and mitigation strategies.

Macroscopic Features and Identification of Lapping Burn

Lapping burn in hypoid gears typically manifests on the tooth surface of the larger gear (driven gear) rather than the pinion. Based on my observations and industry experience, the burned areas are localized and can be characterized by specific macroscopic features. Commonly, the burn occurs near the pitch line but closer to the tooth root, approximately 8–10 mm from the root, with a width of 2–3 mm. On the convex side of the tooth, the burn extends from the central region toward the toe (outer end), while on the concave side, it is symmetrically located around the mid-length of the tooth. Visually, these areas may appear discolored—often showing a bluish or brownish tint—indicative of overheating during lapping. To facilitate identification, I summarize the typical features in Table 1.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Location | Large gear tooth surface, near pitch line toward root |

| Distance from Root | 8–10 mm |

| Width | 2–3 mm |

| Extent on Convex Side | From tooth center to toe |

| Extent on Concave Side | Central symmetric region |

| Visual Appearance | Discoloration (blue/brown), possible surface roughness changes |

Recognizing these features is the first step in addressing lapping burn. In practice, operators should inspect hypoid gears post-lapping under adequate lighting, possibly using magnification or dye penetrants to highlight subtle burn marks. Early detection prevents defective gears from proceeding to assembly, thereby reducing failure risks in automotive applications.

Metallurgical Analysis and Impact on Gear Life

To understand the severity of lapping burn, I conducted metallurgical examinations on samples from burned hypoid gears. The material commonly used for automotive hypoid gears is 22CrMoH2, subjected to carburizing and quenching to achieve a surface hardness of 58–63 HRC and a core hardness of 33–45 HRC, with an effective case depth of 1.7–2.1 mm. When lapping burn occurs, the friction-generated heat elevates the tooth surface temperature. If this temperature exceeds the tempering temperature but remains below Ac1, the surface martensite transforms into tempered troostite or sorbitte, reducing hardness. In severe cases, secondary quenching may produce rehardened martensite.

I prepared cross-sectional samples from burned areas, etched them with 5% nitric alcohol, and observed the microstructure under a microscope. The burned surface layer showed troostite structures with depths ranging from 0.6 to 1.1 mm, whereas unaffected areas exhibited normal martensite and retained austenite. Microhardness testing revealed a significant drop in hardness near the surface, followed by a gradual recovery with depth. The hardness profile can be modeled using an exponential decay function, where the hardness \( H \) at depth \( d \) is given by:

$$ H(d) = H_0 – \Delta H \cdot e^{-k d} $$

Here, \( H_0 \) is the base hardness (e.g., 650 HV), \( \Delta H \) is the hardness loss due to burn, \( k \) is a decay constant, and \( d \) is the depth from the surface. For instance, in a burned sample, the surface hardness might drop to 500 HV, recovering to 600 HV at 0.6 mm depth. This is summarized in Table 2 for a typical hypoid gear.

| Depth from Surface (mm) | Hardness in Burned Area (HV) | Hardness in Unburned Area (HV) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 500 | 650 |

| 0.2 | 520 | 640 |

| 0.4 | 560 | 630 |

| 0.6 | 600 | 620 |

| 1.0 | 620 | 610 |

| 1.5 | 630 | 600 |

The formation of softer troostite reduces wear resistance and fatigue strength. In service, hypoid gears with lapping burn are prone to premature pitting, scuffing, and noise generation. To validate this, I performed rig tests and road tests on burned hypoid gears. Following the JB3803-84 standard, the gears were subjected to 10,000 and 100,000 cycles under load. The burned teeth showed visible wear tracks and micro-pitting after 10,000 cycles, while unburned gears remained intact. Similarly, in vehicle trials, gears with lapping burn exhibited significant surface degradation after 2,000 km of operation. These results underscore that lapping burn directly compromises the durability of hypoid gears, leading to potential field failures and increased warranty costs.

Mechanism of Lapping Burn: Sliding Velocity Analysis

The root cause of lapping burn lies in the excessive frictional heat generated during the lapping of hypoid gears. This heat is primarily due to the relative sliding between the mating tooth surfaces. Hypoid gears have complex kinematics, with sliding occurring along both the tooth profile and length directions. The sliding velocity varies across the tooth contact area, and regions with higher sliding velocities are more susceptible to burn. To analyze this, I developed a mathematical model for the sliding velocity at any meshing point.

Consider a hypoid gear pair with pinion (driver) and gear (driven). Let \( \omega_p \) and \( \omega_g \) be the angular velocities of the pinion and gear, respectively, with a ratio \( R = \omega_p / \omega_g \). At a contact point \( M \) on the tooth surface, the position vectors relative to the axes are \( \mathbf{r}_p \) and \( \mathbf{r}_g \). The surface velocities are:

$$ \mathbf{v}_p = \omega_p \times \mathbf{r}_p, \quad \mathbf{v}_g = \omega_g \times \mathbf{r}_g $$

The relative sliding velocity \( \mathbf{v}_s \) is the difference between the tangential components of these velocities in the contact plane. Decomposing the velocities into components along the instantaneous contact line direction \( \mathbf{t} \) and its perpendicular \( \mathbf{t’} \), we have:

$$ (\mathbf{v}_s)_t = (\mathbf{u}_p)_t – (\mathbf{u}_g)_t, \quad (\mathbf{v}_s)_{t’} = (\mathbf{u}_p)_{t’} – (\mathbf{u}_g)_{t’} $$

where \( \mathbf{u}_p \) and \( \mathbf{u}_g \) are the tangential plane components of \( \mathbf{v}_p \) and \( \mathbf{v}_g \). The magnitude of the sliding velocity is:

$$ v_s = \sqrt{ ((\mathbf{v}_s)_t)^2 + ((\mathbf{v}_s)_{t’})^2 } $$

For hypoid gears, the contact ellipse dimensions change along the tooth due to varying curvature. The semi-major axis \( a \) and semi-minor axis \( b \) of the contact ellipse depend on the local principal curvatures. The sliding velocity is highest near the tooth root region, where the relative motion combines sliding and rolling. Using the above model, I calculated the sliding velocities for a typical hypoid gear pair with parameters: offset 40 mm, ratio 7/48, pinion speed 530 rpm, and torque 0.8 N·m. The results for five points from root to tip are in Table 3.

| Point (Root to Tip) | \( v_{sx} \) (mm/rad) | \( v_{sy} \) (mm/rad) | \( v_s \) (m/s) | Ellipse Semi-major \( a \) (mm) | Ellipse Semi-minor \( b \) (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Near root) | -10.871 | 12.802 | 0.933 | 15.088 | 0.940 |

| 2 | -10.389 | 11.303 | 0.853 | 15.189 | 0.889 |

| 3 | -9.423 | 8.077 | 0.689 | 15.342 | 0.813 |

| 4 | -8.458 | 4.496 | 0.532 | 15.646 | 0.711 |

| 5 (Near tip) | -7.112 | -1.473 | 0.402 | 16.180 | 0.533 |

The data shows that the sliding velocity decreases from root to tip, with the maximum at point 1 (0.933 m/s). This correlates with the observed burn location near the root. During lapping, if the gears are run with zero or minimal backlash, the contact pressure increases, exacerbating frictional heating. The heat generation rate \( \dot{Q} \) can be approximated by:

$$ \dot{Q} = \mu \cdot F_n \cdot v_s $$

where \( \mu \) is the coefficient of friction (typically 0.05–0.1 for abrasive lapping), and \( F_n \) is the normal load. In hypoid gears, the pinion tooth tip may interfere with the gear tooth root during lapping motions, such as when oscillating the pinion axis. Since the gear tooth root has poorer heat dissipation, it becomes the burn site. Thus, controlling lapping parameters, especially backlash, is critical to mitigate burn.

Experimental Validation of Lapping Burn Causes

To verify the role of lapping conditions in burn formation, I conducted a series of experiments using 100 sets of 485-10/37 hypoid gears. The lapping machine was a semi-automatic type with adjustable backlash, load torque, and abrasive supply. The abrasive compound was a mixture of lapping oil and silicon carbide in a 4:1 ratio. I designed four initial trials to screen factors like abrasive flow and backlash, followed by focused tests to isolate key variables. The conditions and outcomes are summarized in Table 4.

| Trial | Abrasive Condition | Backlash (mm) | Load Torque (N·m) | Burn Occurrence | Metallurgical Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No abrasive flow | 0 | 10 | Severe burn | White layer present |

| 2 | Abrasive flow on | 0.10 | 10 | No burn | Normal structure |

| 3 | Abrasive flow on, no refresh | 0.05 | 10 | Mild burn | Troostite layer |

| 4 | Abrasive flow on, no refresh | 0 | 10 | Moderate burn | White layer |

These trials indicated that both abrasive condition and backlash influence burn. To determine the dominant factor, I performed additional tests with 50 gear sets each. In one set, I maintained a backlash of 0.10 mm but withheld abrasive refreshment; after 45 sets, the last 5 showed mild burn. In another set, I varied backlash from 0 to 0.20 mm while refreshing abrasive regularly; all gears lapped at zero backlash exhibited burn with white layers, while those at 0.10 mm or higher were intact. This confirms that zero backlash is a primary driver of lapping burn in hypoid gears. The excessive contact under zero backlash elevates sliding friction, generating heat that cannot be dissipated quickly, especially in the gear tooth root. The abrasive compound helps cool and lubricate, but its effectiveness diminishes if not replenished, as worn abrasives reduce cutting efficiency and increase friction.

Suppression Methods for Lapping Burn

Based on my analysis and experiments, I propose several practical methods to suppress lapping burn in hypoid gears. These focus on process control, equipment upgrades, and operator training.

1. Backlash Control and Automated Monitoring: Maintaining adequate backlash during lapping is paramount. I recommend a backlash range of 0.08–0.15 mm for most hypoid gear applications. Modern CNC lapping machines, such as those with V/H axis control (vertical and horizontal movements), can automatically monitor and adjust backlash in real-time using linear encoders. The backlash adjustment value \( \Delta B \) at each lapping point can be computed via linear interpolation from reference points, ensuring consistent clearance. The control algorithm can be expressed as:

$$ \Delta B = B_{\text{target}} – B_{\text{measured}} $$

where \( B_{\text{measured}} \) is obtained from displacement sensors on the elastic loading mechanism. Implementing such systems reduces human error and prevents zero-backlash conditions.

2. Standardized Operating Procedures: Operator adherence to detailed work instructions is crucial. I developed a set of standard operating procedures (SOPs) for lapping hypoid gears, which include:

- Fixture Setup SOP: Ensuring proper alignment of gear and pinion on the lapping machine.

- Abrasive Management SOP: Specifying the abrasive mix ratio (e.g., 4:1 oil to abrasive) and refreshment schedule (e.g., add 1 kg of new abrasive per 25 gear pairs).

- Lapping Cycle SOP: Defining the lapping time (typically 3 minutes per side), load torque (below 20 N·m), and oscillation range (±2° for pinion).

- Inspection SOP: Checking for burn marks post-lapping using visual or dye penetrant methods.

These SOPs should be documented in “Work Instruction Sheets” and reinforced through regular training.

3. Equipment Advancements: Upgrading from semi-automatic to full CNC lapping machines can significantly reduce burn incidence. Machines like the Gleason 600HTL or Oerlikon L60A offer precise motion control, allowing optimized lapping paths that distribute heat evenly. The V/H adjustment method enables lapping over the entire tooth surface without localized overheating. Additionally, integrating temperature sensors or infrared cameras to monitor tooth surface temperature during lapping can provide early warnings of burn risk.

4. Lapping Parameter Optimization: The lapping process should balance material removal and heat generation. The stock removal amount \( \Delta S \) should be controlled within 0.05–0.10 mm. Excessive removal increases lapping time and heat input. The heat generation can be modeled by integrating the sliding power over the lapping cycle:

$$ Q_{\text{total}} = \int_{0}^{T} \mu F_n(t) v_s(t) \, dt $$

where \( T \) is the lapping duration. By minimizing \( Q_{\text{total}} \) through parameter tuning, burn can be mitigated. For instance, reducing pinion speed or load torque during initial lapping phases lowers heat input.

5. Material and Heat Treatment Considerations: While beyond lapping itself, selecting gear materials with higher thermal conductivity (e.g., copper-alloyed steels) or optimizing heat treatment to increase tempering resistance can reduce burn susceptibility. However, this may involve trade-offs in cost and gear performance.

Conclusion

In this comprehensive study, I investigated the phenomenon of lapping burn in hypoid gears, covering its identification, impact on gear life, underlying mechanisms, experimental validation, and suppression strategies. Lapping burn is a critical yet often overlooked defect that arises from excessive frictional heat during the final finishing of hypoid gears. The burn typically occurs on the large gear tooth surface near the root region, characterized by discoloration and microstructural changes such as troostite formation, leading to hardness reduction and premature failures like pitting and spalling.

Through mathematical modeling, I demonstrated that the sliding velocity is highest in the tooth root area, correlating with burn locations. Experiments confirmed that zero backlash during lapping is a primary cause, as it increases contact pressure and sliding friction. Other factors like abrasive condition and lapping parameters also play roles.

To suppress lapping burn, I recommend implementing automated backlash monitoring systems, adopting CNC lapping machines with V/H control, enforcing standardized operating procedures, and optimizing lapping parameters. These measures not only enhance the quality of hypoid gears but also extend their service life, reducing warranty claims and improving reliability in automotive drivetrains. Future work could explore real-time thermal imaging during lapping or advanced abrasive formulations to further mitigate burn risks. As hypoid gears continue to be integral to vehicle performance, addressing lapping burn remains a vital aspect of gear manufacturing excellence.