The pursuit of precision in mechanical power transmission has long driven innovation in gear design. Among various gear types, spur gears are valued for their simplicity, efficiency, and ease of manufacturing. However, a specialized variant known as the beveloid gear, or involute gear with variable tooth thickness, presents unique advantages for applications demanding minimal backlash, such as in precision reducers and robotic joints. Unlike standard spur gears, beveloid spur gears feature a conical shape where the tooth thickness varies linearly along the face width, allowing for axial adjustment to compensate for wear and assembly errors, effectively achieving zero-backlash operation. This capability makes the analysis of their transmission error (TE)—a critical metric for vibration, noise, and positioning accuracy—particularly significant.

My research focuses on the dynamic transmission error of parallel-axis beveloid spur gears. This work is grounded in gear meshing theory and the specific geometry of variable tooth thickness gears. I developed a mathematical model based on the concept of operating pitch cones for parallel-axis engagement. Subsequently, a precise three-dimensional digital model was constructed, and its kinematic correctness was validated through digital rolling simulation and dynamic analysis using multibody simulation software. To investigate the factors influencing transmission accuracy, a dedicated single-degree-of-freedom dynamic model was established, incorporating dynamic transmission error. This model served as the basis for a comprehensive simulation study analyzing the effects of varying load, rotational speed, and axial installation error on the transmission error of beveloid spur gears. The findings offer valuable insights for the design and application of these precision components.

Theoretical Foundation and Mathematical Modeling

Designing beveloid spur gears for parallel axes cannot rely on the instantaneous axis of rotation, as this does not guarantee the required constant center distance. Therefore, the design must be based on operating pitch cones. The geometry of two mating beveloid spur gears can be described by their respective pitch cones, as shown in the conceptual model. Point M lies on the pitch cone generator, with $γ_{ωj}$ representing the operating pitch cone angle and $\mathbf{n}$ being the unit normal vector. Establishing fixed and gear-bound coordinate systems allows the derivation of the contact condition between the two gear tooth surfaces.

The equation of the pitch cone $Σ_j$ ($j=1,2$ for pinion and gear) in its coordinate system can be expressed as:

$$

\mathbf{R}_j = \begin{bmatrix}

x_j \\

y_j \\

z_j

\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}

u_j \cosθ_j \sinγ_{ωj} \\

u_j \sinθ_j \sinγ_{ωj} \\

u_j \cosγ_{ωj}

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where $u_j$ is the distance from the cone apex to point M, and $θ_j$ is the spread angle in the x-y plane. The unit vector along the cone generator is:

$$

\mathbf{n}_j = \frac{\mathbf{N}_j}{|\mathbf{N}_j|} = \begin{bmatrix}

\cosθ_j \cosγ_{ωj} \\

\sinθ_j \cosγ_{ωj} \\

-\sinγ_{ωj}

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Through coordinate transformations and enforcing the condition of continuous contact (coincident position vectors and collinear but opposite surface normals at the contact point P), the fundamental relationships for parallel-axis beveloid spur gears are derived. The system of equations leads to the conclusion that for proper meshing, the operating pitch cone angles must be equal ($γ_{ω1} = γ_{ω2}$), and the axial offset $d_1$ and shortest distance between cone axes $E$ are given by:

$$

d_1 = (r_{pω1} + r_{pω2}) \cot γ_{ω1}

$$

$$

E = r_{pω1} + r_{pω2}

$$

where $r_{pωj}$ is the operating pitch radius. These equations form the basis for the geometric design and modeling of the gear pair.

Dynamic Model and Transmission Error Definition

To analyze the dynamic behavior and transmission error, a simplified yet effective single-degree-of-freedom torsional vibration model is adopted. This model assumes rigid shafts and bearings and neglects manufacturing errors to isolate the effects of meshing dynamics. The model considers the moments of inertia $I_j$, base circle radii $R_j$, damping coefficients ($c_j$, $c_m$), stiffnesses ($k_j$, $k_m$), and external torques $T_j$.

Applying Newton’s second law to both the driving and driven spur gears yields the equations of motion:

$$

I_1 \ddot{\theta}_1 + R_1 c_m (R_1 \dot{\theta}_1 – R_2 \dot{\theta}_2) – P_1 c_1 \dot{e}_1 – P_2 c_1 \dot{e}_1 + R_1 k_m (R_1\theta_1 – R_2\theta_2) – R_2 k_1 e_1 – R_1 k_2 e_2 = T_1

$$

$$

I_2 \ddot{\theta}_2 + R_2 c_m (R_2 \dot{\theta}_2 – R_1 \dot{\theta}_1) + P_2 c_1 \dot{e}_1 + P_1 c_1 \dot{e}_1 + R_2 k_m (R_2\theta_2 – R_1\theta_1) + R_2 k_1 e_1 + R_1 k_2 e_2 = -T_2

$$

where $\theta_j$, $\dot{\theta}_j$, and $\ddot{\theta}_j$ are the angular displacement, velocity, and acceleration, respectively, and $e_j$ represents profile error. By introducing the Dynamic Transmission Error (DTE) $x = R_1\theta_1 – R_2\theta_2$, the system can be reduced to a single equation. The equivalent mass is $m_e = I_1 I_2 / (I_1 R_2^2 + I_2 R_1^2)$. Considering time-varying mesh stiffness $K(t) = k_m [1 + 2\varepsilon \cos(\omega_m t)]$ and backlash $2b$, the equation of motion becomes:

$$

m_e \ddot{x} + c_m \dot{x} + k_m [1 + 2\varepsilon \cos(\omega_m t)] f(x) = W

$$

where $W$ is the static load and $f(x)$ is a piecewise function accounting for backlash:

$$

f(x) =

\begin{cases}

x – b, & x > b \\

0, & -b \le x \le b \\

x + b, & x < -b

\end{cases}

$$

Transmission error quantifies the deviation from ideal motion transfer. For a gear pair with constant input speed, it is conveniently defined as the difference between the actual angular position of the driven gear and its theoretical position based on the perfect gear ratio. An alternative definition, which I employ for dynamic simulation analysis, is based on angular velocities:

$$

TE = \omega_{driven} – \frac{N_{driver}}{N_{driven}} \cdot \omega_{driver}

$$

where $\omega$ represents angular velocity and $N$ is the number of teeth. This TE signal, typically oscillating around zero, is a direct indicator of meshing smoothness and dynamic excitation in spur gears and their beveloid variants.

Digital Model Generation and Validation

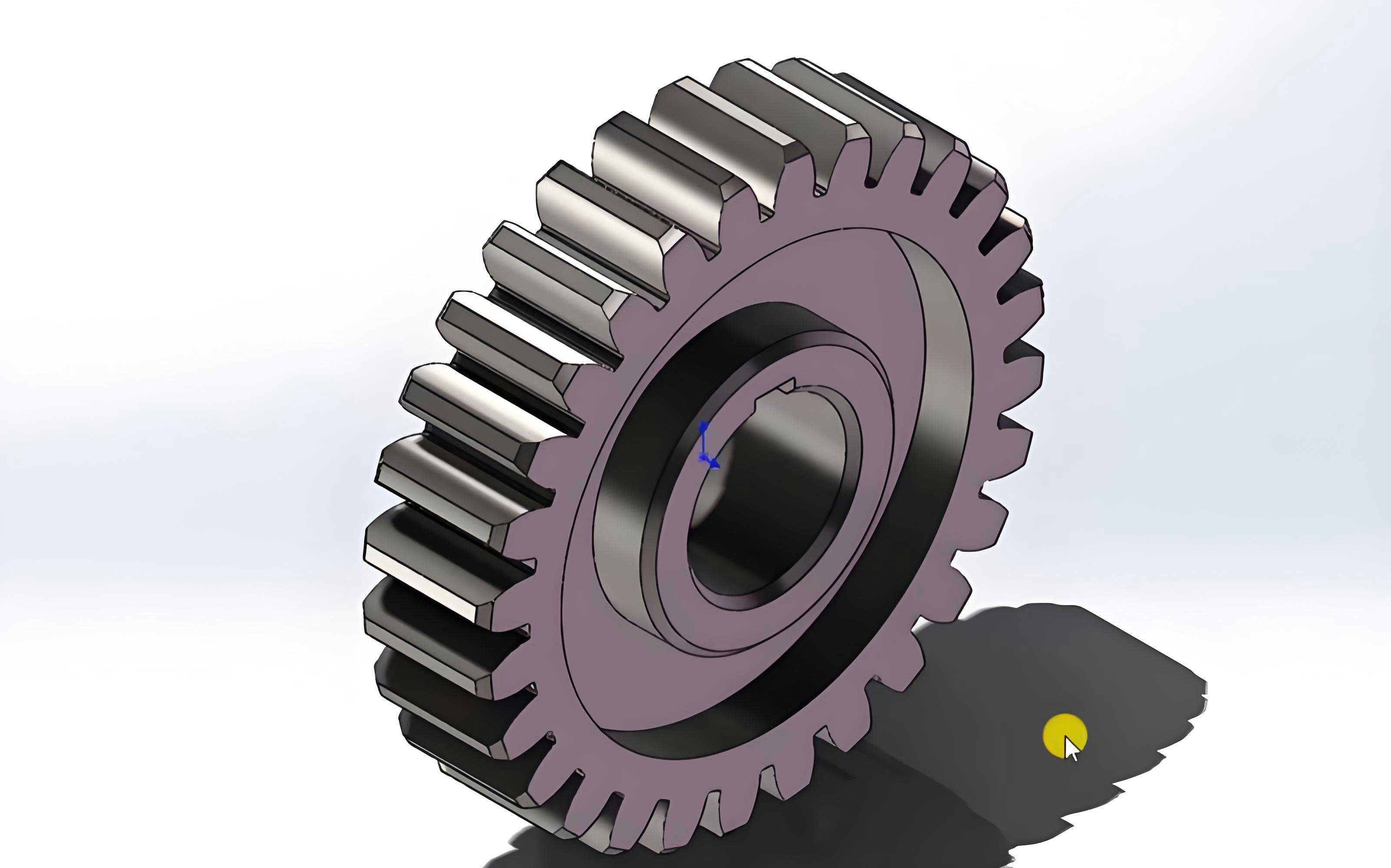

Generating an accurate 3D model of beveloid spur gears is essential for subsequent analysis. Using the derived pitch cone geometry and standard involute equations adjusted for linearly varying addendum modification (profile shift) across the face width, a cloud of points defining the tooth flank was calculated. These points were interpolated to form spline curves and surfaces within CAD software, ultimately generating a solid model of a gear pair. The primary parameters for the modeled beveloid spur gear pair are summarized in the following table:

| Parameter | Pinion | Gear |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Module (mm) | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Number of Teeth | 25 | 37 |

| Pressure Angle (deg) | 20 | 20 |

| Face Width (mm) | 28 | 26 |

| Pitch Cone Angle (deg) | 6 | 6 |

| Profile Shift at Small End | 0.010 | 0.008 |

| Center Distance (mm) | 80 | |

The model’s correctness was verified in two stages. First, a digital roll test was performed within the CAD environment, simulating the meshing process. The observation of a smooth, continuous line of contact across the tooth flanks confirmed the geometric integrity of the tooth surfaces and their conjugacy.

Second, the model was imported into a multibody dynamics software (ADAMS) for kinematic validation. A constant speed of 800 rpm was applied to the driver, and a load of 200 N·m was applied to the driven beveloid spur gear. The simulation yielded an average output speed of approximately 319.74 rpm. The resulting transmission ratio was 2.502, which deviates by only 0.08% from the theoretical ratio of 2.5 (37/25). This negligible error confirms the kinematic accuracy of the generated digital model, providing a reliable foundation for dynamic transmission error analysis.

Analysis of Transmission Error Under Different Operating Conditions

Using the validated dynamic model, I systematically investigated the influence of three key operational parameters on the transmission error of the beveloid spur gear pair. To ensure analysis of steady-state conditions, data from the stable meshing period (0.02 s to 0.1 s) of each simulation was used.

Effect of Load on Transmission Error

The load on the driven gear was varied from 50 N·m to 250 N·m in increments of 50 N·m, while maintaining a constant input speed of 360 rpm. The transmission error signals for all cases exhibited periodic fluctuations around the zero line, characteristic of stable meshing in spur gears. However, the amplitude of these fluctuations changed with load.

To quantify this, key statistical metrics of the TE signal were extracted: the maximum TE ($TE_{max}$), minimum TE ($TE_{min}$), and the root mean square ($TE_{RMS}$), which represents the overall magnitude of variation. The results are consolidated in the table below:

| Load (N·m) | $TE_{max}$ (arcsec) | $TE_{min}$ (arcsec) | $TE_{RMS}$ (arcsec) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 15.2 | -14.8 | 6.1 |

| 100 | 21.5 | -21.0 | 8.9 |

| 150 | 26.1 | -25.7 | 10.8 |

| 200 | 29.4 | -29.1 | 12.2 |

| 250 | 31.5 | -31.3 | 13.1 |

The trend is clear: all three error metrics increase with applied load. This is attributed to increased elastic deformation of the teeth, housing, and shafts under higher torque. The relationship is non-linear, with the rate of increase in TE diminishing at higher loads, suggesting a gradual saturation of the system’s compliance. This behavior is crucial for designers of precision systems using beveloid spur gears, indicating that while load increases error, the sensitivity to load changes decreases at higher torque levels.

Effect of Rotational Speed on Transmission Error

In this study, the input rotational speed was varied from 400 rpm to 800 rpm, while a constant load of 200 N·m was maintained. The transmission error signals remained periodic but showed a noticeable shift in their mean value and an increase in amplitude with higher speeds.

The extracted error metrics reveal a strong dependence on speed:

| Speed (rpm) | $TE_{max}$ (arcsec) | $TE_{min}$ (arcsec) | $TE_{RMS}$ (arcsec) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400 | 22.8 | -23.5 | 9.7 |

| 500 | 26.5 | -27.1 | 11.4 |

| 600 | 29.4 | -29.1 | 12.2 |

| 700 | 32.8 | -31.6 | 13.4 |

| 800 | 36.5 | -34.9 | 15.0 |

The increase in $TE_{max}$, $TE_{min}$, and $TE_{RMS}$ with rotational speed is approximately linear within this range. This linear trend highlights a significant sensitivity of beveloid spur gear transmission error to speed variations. The primary mechanisms are the increased inertial forces and more severe meshing impacts at higher speeds, which excite the dynamic system more strongly. Unlike the saturating trend with load, the effect of speed on TE appears more consistently proportional, a critical consideration for high-speed applications of these gears.

Effect of Axial Installation Error on Transmission Error

A key feature of beveloid spur gears is their ability to adjust backlash through axial displacement. I simulated this by introducing a deliberate axial misalignment (installation error) $\Delta A$ between the gears, starting from the nominal position where the small end of the pinion faces the large end of the gear. Errors from 0 mm to 1.5 mm were introduced. The input speed was 600 rpm and load 200 N·m.

The results challenge intuitive expectations. One might assume that any misalignment would degrade performance. However, the analysis of beveloid spur gears shows a more nuanced relationship:

| Axial Error $\Delta A$ (mm) | $TE_{max}$ (arcsec) | $TE_{min}$ (arcsec) | $TE_{RMS}$ (arcsec) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 29.4 | -29.1 | 12.2 |

| 0.3 | 28.1 | -29.5 | 12.3 |

| 0.6 | 27.0 | -30.8 | 12.7 |

| 0.9 | 26.9 | -31.1 | 12.9 |

| 1.2 | 27.5 | -30.5 | 12.6 |

| 1.5 | 28.3 | -29.7 | 12.4 |

The data reveals an “M-shaped” trend. As the axial error increases from zero, the maximum TE initially decreases, reaching a minimum around $\Delta A = 0.9$ mm, before increasing again. Conversely, the minimum TE becomes more negative (larger in magnitude) initially before recovering. The $TE_{RMS}$ shows a slight increase followed by a decrease. This behavior suggests that a small, controlled axial displacement can alter the contact pattern and load distribution across the tooth face of the beveloid spur gears, potentially leading to a more favorable meshing condition that slightly reduces peak transmission error. This finding underscores the built-in compensatory capability of beveloid spur gears, where axial adjustments meant for backlash control can have a secondary, marginally beneficial effect on dynamic transmission error.

Conclusion

This investigation into the transmission error of parallel-axis involute beveloid spur gears, combining theoretical modeling with dynamic simulation, yields several important conclusions. The developed pitch cone model and digital prototyping methodology proved effective for accurately representing this specialized gear geometry. The dynamic analysis reveals distinct influences of operational parameters:

1. Under ideal alignment, beveloid spur gears exhibit low transmission error that fluctuates periodically around zero, indicating stable and precise meshing suitable for high-accuracy applications.

2. Increasing the transmitted load causes a rise in transmission error magnitude due to enhanced elastic deformations. However, this relationship is non-linear, with the error growth rate diminishing at higher torque levels, eventually tending toward a stable value.

3. Rotational speed has a pronounced and approximately linear influence on transmission error. Higher speeds lead to a significant increase in error amplitude, primarily due to greater inertial effects and meshing impacts. This makes speed a critical factor for noise and vibration in high-speed beveloid spur gear drives.

4. Contrary to initial assumptions, small axial installation errors—inherent to the backlash adjustment function of beveloid spur gears—do not drastically degrade transmission error. The error metrics show an “M-shaped” variation with increasing axial offset, suggesting the possibility of an optimal axial position that minimizes peak error. This demonstrates the robustness of the design to assembly variations.

These findings provide a foundation for optimizing the design and operational parameters of beveloid spur gear systems to minimize transmission error, thereby improving dynamic performance, reducing vibration and noise, and enhancing positioning accuracy in precision mechanical transmissions.