In the realm of modern manufacturing, the cold precision forging of spur gears represents a significant advancement due to its ability to produce high-quality components with minimal material waste and reduced machining steps. However, the closed-die forging of spur gears, especially those with large modules, presents considerable challenges, including high forming loads, difficulty in filling intricate tooth profiles, and reduced die life. To address these issues, we have developed and investigated two novel divided flow processes: the open-type divided flow method and the tooth-top divided flow method. These approaches, combined with floating die technology, aim to lower forming pressures, enhance filling performance, and promote the practical application of cold forging for spur gears. In this article, I will detail our simulation and experimental studies, comparing these methods with conventional axial divided flow techniques, and provide insights through extensive analysis, tables, and mathematical formulations.

The fundamental principle behind divided flow forging lies in managing material deformation to reduce ideal deformation resistance and frictional forces. The ideal deformation pressure, \( p \), can be expressed as:

$$p = y \ln \frac{R}{1-R}$$

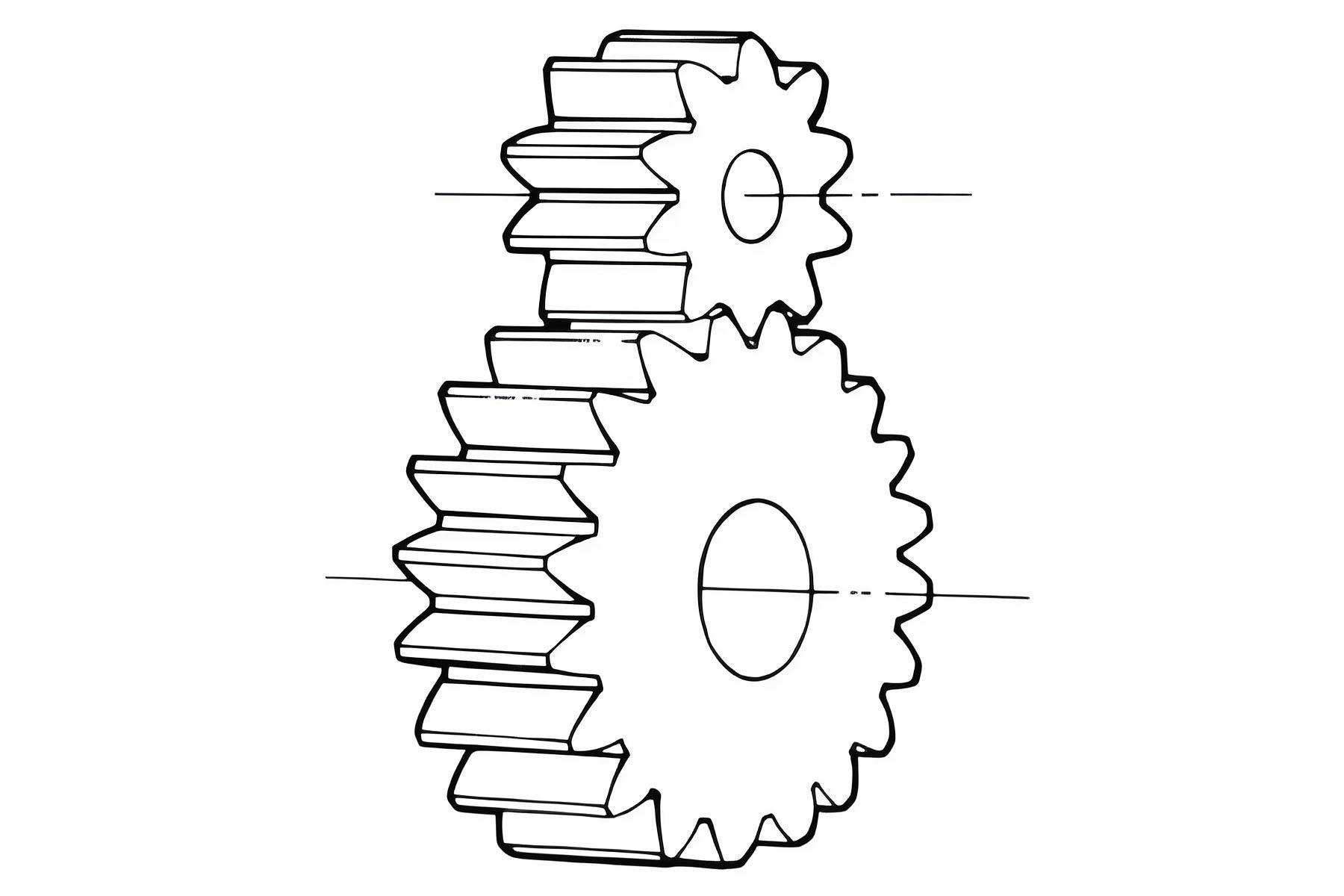

where \( y \) is the nominal flow stress of the material, and \( R \) is the relative area reduction ratio. By introducing divided cavities, we increase the free surface area during forging, thereby decreasing \( R \) and subsequently lowering the required forming load. This concept is crucial for spur gear forging, where the final stages of filling tooth corners and edges typically cause a sharp rise in pressure. Our research focuses on optimizing this process for spur gears with a module of 3 mm, 25 teeth, a pressure angle of 20°, and a height of 15 mm, which are representative of industrial applications.

We propose two distinct divided flow strategies. The first, termed the open-type divided flow method, involves extending the die tooth cavity beyond the standard profile by 1 mm, creating an overflow cavity at the tooth tips. This allows material to flow freely into this region once the critical corners are filled, avoiding the high-load final filling phase. The second method, the tooth-top divided flow, incorporates a annular groove on the punch corresponding to the tooth tips, with dimensions of 4 mm × 3 mm in cross-section. This groove facilitates material diversion specifically at the最难充填的 tooth top areas, improving filling and reducing load. For comparison, we also examine a conventional axial divided flow process, where a central hole of 8 mm diameter is machined into the punch. All processes utilize a floating die mechanism, where both the punch and die move downward simultaneously to enhance material flow and reduce friction.

To evaluate these processes, we conducted numerical simulations using DEFORM-3D software, based on rigid-plastic finite element analysis. The workpiece material was modeled as AISI-4120 steel, with a custom constitutive relation from the software library. The initial billet dimensions were calculated from volume conservation to be 67 mm in diameter and 20 mm in height. We applied localized meshing to areas of high deformation, such as the tooth regions. The forming temperature was set to room temperature (20°C), neglecting thermal effects, and a friction factor of 0.1 was used to simulate phosphating and saponification treatment. The punch and floating die speeds were both 1 mm/s. The simulation models for the three schemes are summarized in Table 1, highlighting key features.

| Scheme | Description | Divided Cavity Details |

|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1: Axial Divided Flow | Central hole in punch for axial material flow | Diameter: 8 mm |

| Scheme 2: Tooth-Top Divided Flow | Annular groove on punch at tooth tips | Cross-section: 4 mm × 3 mm; Outer diameter equals gear tip diameter |

| Scheme 3: Open-Type Divided Flow | Extended die cavity beyond standard tooth profile | Extension: 1 mm beyond tooth tip line |

The simulation results revealed significant differences in filling behavior and load requirements. For Scheme 1, the final filling stage showed minor unfilled arcs at the tooth tips, though these could be tolerated with subsequent chamfering. The equivalent strain distribution indicated that deformation concentrated primarily in the tooth roots, which is typical for spur gear forging. Scheme 2 demonstrated complete filling of tooth corners, with excess material forming protrusions at the tooth tops that can be easily machined off. Scheme 3, in contrast, stopped loading once the tooth tips exceeded the standard profile, leaving large arcs at the tops but ensuring full corner filling. This approach maintained a large free surface, preventing the sharp load increase seen in other methods. The friction force distribution, both axial and radial, played a key role: in Schemes 1 and 3, radial friction hindered full tip filling, whereas Scheme 2’s groove eliminated this issue by providing a direct flow path.

The forming load-stroke curves from simulation are critical for assessing process efficiency. As shown in Table 2, Scheme 3 achieved the lowest final load at 91.7 tons, representing reductions of 38.8% and 32.6% compared to Schemes 1 and 2, respectively. Scheme 2 also showed improvement over Scheme 1, with a 10.3% load decrease. This highlights the efficacy of divided flow methods in reducing pressures, which directly correlates with extended die life and energy savings. The load reduction can be further analyzed using the deformation pressure formula. For instance, in Scheme 3, the relative area reduction \( R \) remains low due to the open cavity, leading to a smaller \( p \) value. We can express the total forming force \( F \) as:

$$F = A \cdot p = A \cdot y \ln \frac{R}{1-R}$$

where \( A \) is the contact area. By designing divided cavities, we effectively control \( R \) and \( A \), optimizing \( F \) for spur gear production.

| Scheme | Final Forming Load (Simulation, tons) | Load Reduction vs. Scheme 1 | Filling Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1: Axial Divided Flow | 150.0 | Baseline | Partial unfilled arcs at tooth tips |

| Scheme 2: Tooth-Top Divided Flow | 136.0 | 10.3% | Complete corner filling, protrusions at tops |

| Scheme 3: Open-Type Divided Flow | 91.7 | 38.8% | Full corner filling, large arcs at tops |

To validate these simulations, we performed physical experiments using industrial pure lead as a model material, due to its similar plastic behavior at room temperature. A 200-ton torsion hydraulic press was employed, and three sets of simplified dies were fabricated for each scheme. The experimental results aligned closely with simulation predictions. For Scheme 1, at a load of 72 tons, the central hole filled significantly, but tooth tips exhibited圆弧 defects, consistent with simulation. Scheme 2 required only 56 tons, forming distinct protrusions at tooth tops with excellent filling—a 22.2% load reduction versus Scheme 1. Scheme 3 achieved forming at 42 tons, with the divided cavity unfilled and tooth tips showing large arcs, yet exceeding the standard profile. This corresponds to load reductions of 41.7% and 25% compared to Schemes 1 and 2, respectively. The experimental data, summarized in Table 3, confirm the superiority of divided flow processes for spur gear forging.

| Scheme | Experimental Load (tons) | Load Reduction vs. Scheme 1 | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1: Axial Divided Flow | 72.0 | Baseline | Central hole filled, tooth tips have arcs |

| Scheme 2: Tooth-Top Divided Flow | 56.0 | 22.2% | Protrusions formed, full tooth filling |

| Scheme 3: Open-Type Divided Flow | 42.0 | 41.7% | Divided cavity unfilled, tooth tips arcs exceed profile |

The material flow during spur gear forging is complex, involving multi-axial stresses and strains. We can model the effective strain \( \bar{\epsilon} \) using the von Mises criterion, which for our processes shows concentration in tooth roots, as seen in simulation contours. The strain distribution affects the final mechanical properties of the spur gear, such as strength and fatigue resistance. By preserving fibrous tissue in the tooth faces through minimal machining—only turning the outer circle for Scheme 3 or milling the end face for Scheme 2—we maintain the integrity of these properties. This is a key advantage over traditional cutting methods that disrupt material flow lines.

Further analysis of friction effects is essential. The friction force \( F_f \) can be expressed as:

$$F_f = \mu \cdot p_n \cdot A_f$$

where \( \mu \) is the friction factor (0.1 in our case), \( p_n \) is the normal pressure, and \( A_f \) is the friction area. In Schemes 1 and 3, the radial friction at tooth tips increases \( A_f \), hindering filling. Scheme 2 reduces this by diverting material axially into the groove. This insight helps in designing optimal die geometries for spur gear forging.

We also explored the impact of billet dimensions on process outcomes. Using volume conservation, the initial billet volume \( V \) is:

$$V = \frac{\pi}{4} d^2 h$$

where \( d \) is diameter and \( h \) is height. For our spur gear, \( V \) was matched to the final forged volume, ensuring minimal flash. The choice of billet size influences the initial \( R \) value in the deformation pressure equation, affecting overall loads. Through iterative simulation, we optimized billet dimensions to balance filling and load.

The role of floating die technology cannot be overstated. By allowing the die to move with the punch, we reduce relative velocities and shear stresses, further lowering frictional resistance. This synergy with divided flow methods enhances material flow into tooth cavities, making it particularly beneficial for spur gears with large modules. The combined effect can be quantified by adjusting the friction factor in simulations, but our experimental setup already incorporated this feature.

In terms of practical application, the open-type divided flow method offers the most significant load reduction, making it ideal for high-volume production of spur gears. The tooth-top divided flow method provides better filling for components requiring precise tip geometry. Both methods surpass conventional axial divided flow in efficiency and outcome. For instance, in automotive or aerospace industries, where spur gears are critical for transmission systems, these processes can lead to substantial cost savings and improved part performance.

To deepen our understanding, we derived a comprehensive model for forming load prediction. The total load \( L \) is the sum of ideal deformation force \( F_i \), friction force \( F_f \), and any redundant work force \( F_r \):

$$L = F_i + F_f + F_r$$

For spur gear forging, \( F_i \) dominates and is given by the pressure integral over the contact area. Using the divided flow approach, we can approximate \( F_i \) as:

$$F_i = \int_A y \ln \frac{R(x)}{1-R(x)} \, dA$$

where \( R(x) \) varies spatially due to the complex gear geometry. Numerical integration via finite element analysis, as we performed, provides accurate values. Our simulations show that Schemes 2 and 3 reduce \( F_i \) by lowering \( R(x) \) at critical points.

Additionally, we considered material property variations. The flow stress \( y \) for AISI-4120 steel can be modeled using the Hollomon equation:

$$y = K \epsilon^n$$

where \( K \) is the strength coefficient, \( \epsilon \) is the true strain, and \( n \) is the strain-hardening exponent. In cold forging, strain hardening increases \( y \) during deformation, but divided flow methods mitigate this by distributing strain more evenly. This contributes to lower overall pressures for spur gear forming.

The experimental validation with lead, while simplifying thermal effects, confirms the mechanical principles. Scaling to steel involves higher loads but proportional benefits. We estimate that for steel spur gears, the load reductions would follow similar percentages, though absolute values would be higher due to greater \( y \). This underscores the universality of divided flow techniques for cold forging various materials.

In conclusion, our simulation and experimental studies demonstrate that the open-type and tooth-top divided flow processes, combined with floating die technology, significantly improve the cold precision forging of spur gears. Compared to conventional axial divided flow, these methods reduce forming loads by up to 41.7%, enhance tooth corner filling, and allow for minimal post-forging machining that preserves material fiber lines. The open-type method is particularly effective for load reduction, while the tooth-top method excels in filling performance. These advancements pave the way for broader adoption of cold forging in spur gear manufacturing, offering economic and quality benefits. Future work could explore optimization of divided cavity geometries for different spur gear parameters or integrate these processes with advanced materials, further pushing the boundaries of precision forming.

Throughout this research, the focus on spur gear forging has been paramount, and the repeated emphasis on spur gear processes underscores their importance in modern engineering. By leveraging mathematical models, numerical simulations, and physical trials, we have developed robust solutions that address long-standing challenges in cold forging of spur gears. The insights gained here can be extended to other gear types, but the core principles remain anchored in the efficient deformation management of spur gear profiles. As industry demands for high-performance, cost-effective components grow, such innovative forging techniques will play a crucial role in meeting those needs.