High-power, high-speed drive systems are critical components in demanding sectors such as energy generation, aerospace, and heavy industrial machinery. The pursuit of higher power density, efficiency, and reliability constantly pushes the boundaries of mechanical transmission design. Among various gear types, herringbone gears offer a compelling solution due to their inherent ability to minimize axial thrust loads, provide smooth meshing action, and offer high load-carrying capacity. The double-helical arrangement effectively cancels out axial forces, eliminating the need for complex thrust bearings and simplifying system design. However, as operational speeds increase, the dynamic behavior of these transmission systems becomes paramount. Vibrations induced by internal excitations (e.g., time-varying mesh stiffness, transmission errors) and external loads can compromise transmission accuracy, generate excessive noise, accelerate fatigue, and ultimately threaten operational stability and longevity. Therefore, optimizing the dynamic performance of herringbone gear transmission systems is not merely an enhancement but a necessity for modern high-performance applications.

Traditional dynamic optimization often focuses on deterministic models, seeking optimal design parameters that minimize a target function, such as vibration amplitude or stress, under ideal conditions. Yet, real-world manufacturing, assembly, and operation are fraught with uncertainties. Variations in material properties, dimensional tolerances, bearing clearances, and load conditions are inevitable. A design optimized deterministically might perform excellently in simulation but could become sensitive or even unstable when these inherent variations are present. This gap highlights the need for robust optimization methodologies. Robust design optimization aims to find solutions where the performance objective is not only optimal on average but also exhibits minimal sensitivity to fluctuations in design variables and noise factors. The 6σ robust optimization framework, rooted in quality engineering, is a powerful approach to achieve this. It seeks to ensure that the probability of the design meeting its performance targets is extremely high (theoretically 99.99966% under a normal distribution for a 6σ process), even when input parameters vary within their expected ranges.

This work presents a comprehensive framework for the robust dynamic optimization of a high-speed herringbone gear transmission system. We begin by establishing a detailed finite element model to capture the system’s dynamic characteristics. Subsequently, we employ a 6σ robust optimization strategy to minimize housing vibration, treating key structural dimensions as uncertain variables. The approach ensures the optimized design maintains superior vibration performance with high reliability under realistic conditions of variability.

1. Dynamic Modeling and Vibration Analysis of the Herringbone Gear System

1.1 Finite Element Model Development

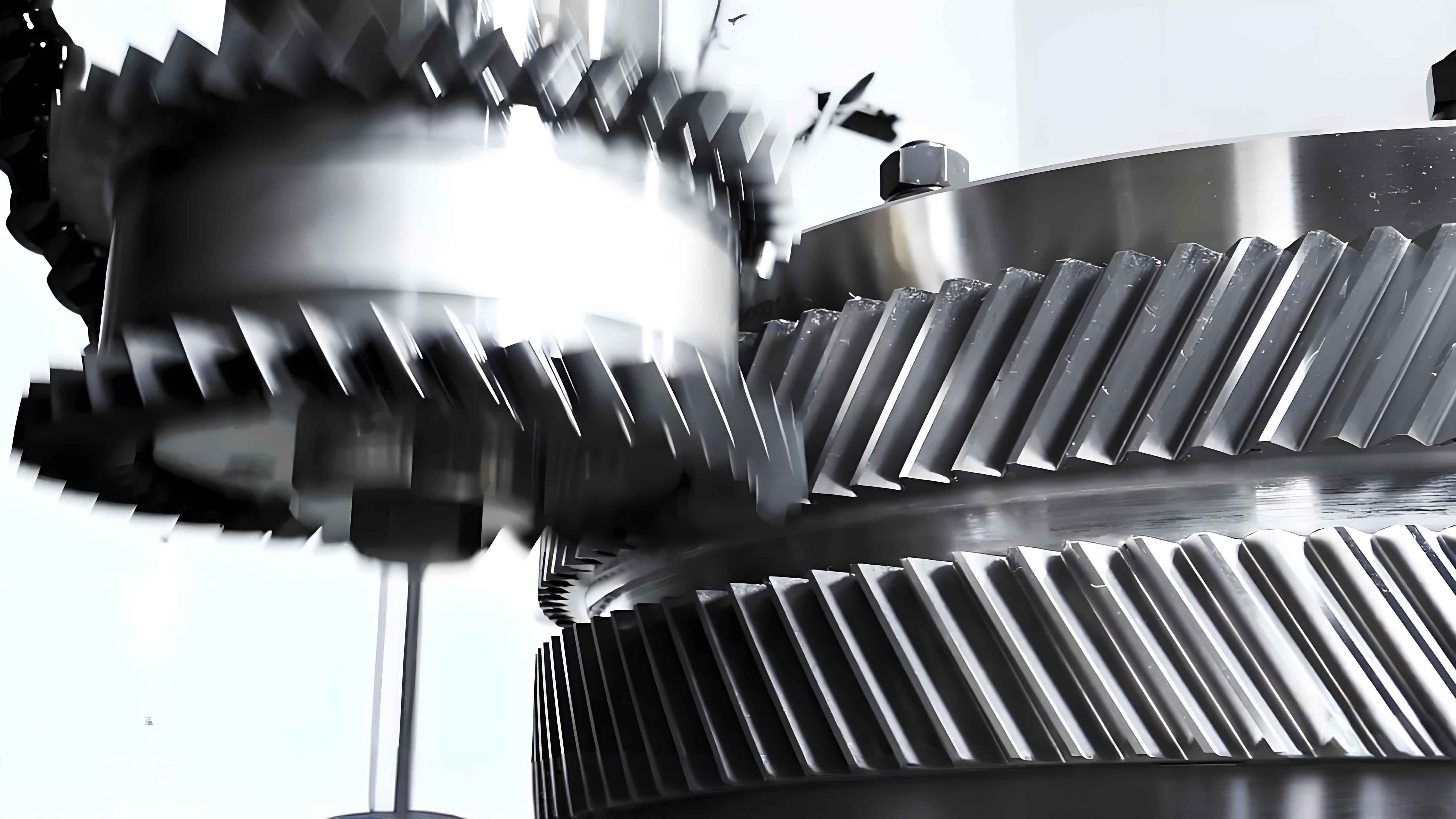

The subject of this study is a single-stage, high-speed herringbone gear transmission. The system comprises a pinion and a gear, each supported by two sliding bearings housed within a rigid structure. The primary parameters of the herringbone gear pair are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Symbol | Pinion | Gear | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth | z | 46 | 92 | – |

| Normal Module | mn | 7 | mm | |

| Normal Pressure Angle | αn | 25 | ° | |

| Face Width (per helix) | b | 30 | mm | |

| Helix Angle | β | 23.38 | ° | |

| Center Distance | a | 530 ± 0.0315 | mm | |

| Material Density | ρ | 7850 | kg/m³ | |

| Young’s Modulus | E | 210 | GPa | |

| Poisson’s Ratio | ν | 0.3 | – | |

A high-fidelity finite element model is developed using commercial software. The gears, shafts, and housing are meshed with 3D solid elements. To balance computational accuracy and efficiency, hexahedral elements are primarily used for the rotating components and key housing regions, while tetrahedral elements fill complex geometries. The model’s connection integrity is paramount; the gear-shaft connections are modeled as bonded, and the shaft-bearing connections are critically represented. The dynamic coefficients (stiffness and damping) for the hydrodynamic sliding bearings are calculated under the rated operating condition using specialized rotor dynamics software. These coefficients, which are functions of speed and load, are then incorporated into the model using spring-damper elements at the bearing locations. The calculated bearing dynamic coefficients are presented in Table 2.

| Bearing Location | Stiffness (106 N/m) | Damping (103 N·s/m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kxx | kyy | cxx | cyy | |

| High-Speed Shaft | 585.9 | 876.3 | 1.015 | 3.259 |

| Low-Speed Shaft | 696.8 | 570.9 | 1.849 | 3.241 |

*Cross-coupled terms (kxy, kyx, cxy, cyx) are present but omitted for table clarity, focusing on direct coefficients.

The external load is applied as a torque on the low-speed shaft, while the high-speed shaft is driven at a constant rotational speed. The most significant internal excitation in geared systems is the time-varying mesh stiffness (TVMS). For herringbone gears, the combined mesh stiffness can be considered as the parallel sum of the stiffnesses from the two helices. The TVMS is obtained through a detailed finite element analysis of a gear pair segment under load. For multiple positions across the mesh cycle, the static transmission error is computed, and the mesh stiffness \( K_m \) is derived from the applied torque \( T \) and the resulting angular deflection \( \Delta\theta \):

$$ K_T = \frac{T}{\Delta\theta} $$

The individual gear body stiffness \( K_{gear} \) is also calculated. The net mesh stiffness at a given position is then found from the series combination of the pinion and gear flexibilities, often dominated by the tooth pair contact stiffness \( K_{contact} \):

$$ \frac{1}{K_m} = \frac{1}{K_{contact, pinion}} + \frac{1}{K_{contact, gear}} + \frac{1}{K_{body, pinion}} + \frac{1}{K_{body, gear}} $$

This calculation is repeated across the mesh cycle to generate the periodic TVMS function, \( K_m(t) \), which is applied as a forcing function along the line of action in the dynamic model.

1.2 Modal Analysis: Assessing Resonance Risk

Before performing transient dynamic analysis, a modal analysis is conducted to identify the natural frequencies and mode shapes of the overall system—including housing, shafts, and gears. This step is crucial to ensure that the excitation frequencies during operation do not coincide with system resonances, which would lead to catastrophic vibration amplitudes. The first eight natural frequencies and their dominant characteristics are listed in Table 3.

| Mode | Natural Frequency (Hz) | Primary Mode Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 131.16 | Global torsional vibration of shafts & housing sway in lateral direction. |

| 2 | 164.98 | 1st bending of low-speed shaft & housing sway in perpendicular direction. |

| 3 | 202.49 | Axial “breathing” mode of the housing. |

| 4 | 209.09 | Combined shaft bending and housing torsion about vertical axis. |

| 5 | 238.18 | Housing base distortion coupled with shaft motion. |

| 6 | 282.47 | Axial deformation of the housing base. |

| 7 | 307.48 | Complex housing torsion with shaft bending. |

| 8 | 316.59 | Housing base rocking mode. |

The rated operational speed of the high-speed shaft is 6000 rpm, corresponding to a rotational frequency (1X) of \( f_r = 100 \) Hz. The primary meshing frequency for the herringbone gear pair is \( f_m = z_1 \times f_r = 46 \times 100 = 4600 \) Hz. Comparing these excitation frequencies with the lower-order natural frequencies in Table 3 confirms a significant separation. Neither the shaft speed nor the fundamental meshing frequency is close to any of the first eight system modes, indicating a low risk of resonance during normal operation. This safe margin is a prerequisite for effective dynamic optimization focused on forced vibration response.

1.3 Dynamic Response and Baseline Vibration

The forced dynamic response of the system is computed using the modal superposition method, an efficient technique for linear systems. The excitation includes the applied torque and the time-varying mesh stiffness \( K_m(t) \). A transient analysis is performed over a sufficient time duration (0.1 s) to capture steady-state vibration, with a time step small enough to resolve the meshing frequency.

The vibration response is evaluated at key locations on the gearbox housing, typically directly above the bearing supports where vibration transmission from the gear mesh is most direct. Four such evaluation points are selected. The output of interest is the vibration acceleration. The time-domain acceleration signals (\( a_x(t), a_y(t), a_z(t) \)) at each point are processed to calculate the Root Mean Square (RMS) value, a robust metric for overall vibration level:

$$ a_{RMS, dir} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{T} \int_0^T a_{dir}^2(t) \, dt} $$

where \( dir \) represents the x, y, or z direction, and \( T \) is the analysis period. The baseline RMS vibration levels for the four evaluation points are summarized in Table 4. Point 1, located near the input (high-speed) bearing, exhibits the highest vibration levels, establishing the baseline for optimization.

| Evaluation Point | RMS Acceleration (m/s²) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| x-direction | y-direction | z-direction | |

| 1 | 58.81 | 44.08 | 42.86 |

| 2 | 50.34 | 46.17 | 41.66 |

| 3 | 49.87 | 43.82 | 38.86 |

| 4 | 57.78 | 54.40 | 39.23 |

2. Robust Dynamic Optimization Methodology

2.1 The 6σ Robust Optimization Framework

Deterministic optimization finds a design point \( X^* \) that minimizes an objective function \( f(X) \) subject to constraints \( g_j(X) \leq 0 \). However, when design variables \( X \) are subject to manufacturing variations or uncertainties, the performance \( f \) and constraint compliance \( g_j \) become random variables. A deterministically optimal point might lie on a steep performance cliff, where small deviations in \( X \) cause large, unacceptable degradations in \( f \) or cause constraints to be violated.

Robust optimization counters this by seeking a design that is optimal and insensitive to variations. The 6σ method formalizes this by treating uncertainties statistically. It aims to shift the mean performance \( \mu_f \) to an optimal value while simultaneously minimizing the standard deviation \( \sigma_f \) (i.e., reducing sensitivity). Furthermore, it ensures that the probability of violating constraints is extremely low, typically corresponding to a Six Sigma quality level (≈ 2 defects per billion events for a normally distributed process under shift). The mathematical formulation of a 6σ robust optimization problem is:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \text{Minimize:} \quad \mu_f(X) + \kappa \sigma_f(X) \\

& \text{Subject to:} \quad \mu_{g_j}(X) + \lambda_j \sigma_{g_j}(X) \leq 0, \quad j = 1,…,m \\

& \qquad \qquad X^L + n \sigma_X \leq \mu_X \leq X^U – n \sigma_X

\end{aligned}

$$

Here:

– \( \mu_f, \sigma_f \) are the mean and standard deviation of the objective function.

– \( \kappa \) is a weight factor balancing mean performance and robustness (a higher \( \kappa \) puts more emphasis on reducing variation).

– \( \mu_{g_j}, \sigma_{g_j} \) are the mean and standard deviation of the j-th constraint.

– \( \lambda_j \) is the Sigma level index for the constraint (e.g., \( \lambda = 6 \) for a 6σ requirement).

– \( \mu_X, \sigma_X \) are the means and standard deviations of the design variables.

– \( X^L, X^U \) are the lower and upper bounds of the design variables.

– \( n \) defines the Sigma-level margin for the design variables themselves, ensuring they are not too close to their bounds given their variation \( \sigma_X \).

For our case, the objective is to minimize the housing vibration. The constraint is implicit: the system must remain functional (no resonance, stress limits). The design variable bounds are explicit manufacturing limits.

2.2 Definition of Optimization Problem for the Herringbone Gearbox

Objective Function: The goal is to minimize the overall vibration level of the gearbox housing. We define the objective function as the average of the RMS vibration accelerations across the four evaluation points and three spatial directions:

$$ f(X) = \frac{1}{12} \sum_{p=1}^{4} \sum_{dir \in \{x,y,z\}} a_{RMS}^{(p, dir)}(X) $$

where \( X \) is the vector of design variables.

Design Variables and Uncertainty: Seven key geometric parameters of the gearbox housing are initially considered as potential design variables: baseplate thickness (\(x_1\)), internal rib thickness (\(x_2\)), reinforcement rib thickness (\(x_3\)), connector block thickness (\(x_4\)), crossbeam thickness (\(x_5\)), main housing wall thickness (\(x_6\)), and cover thickness (\(x_7\)). These dimensions inherently possess manufacturing tolerances. We model them as independent random variables following normal distributions. Their nominal (mean) values are to be optimized within specified ranges, and each has a prescribed standard deviation \( \sigma \) representing its manufacturing tolerance. The initial values and ranges are shown in Table 5.

| Variable | Description | Initial Mean (mm) | Range (mm) | Distribution (Std. Dev.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x₁ | Baseplate Thickness | 14 | 9 – 19 | Normal (σ₁) |

| x₂ | Internal Rib Thickness | 24 | 19 – 29 | Normal (σ₂) |

| x₃ | Reinforcement Rib Thickness | 10 | 5 – 15 | Normal (σ₃) |

| x₄ | Connector Block Thickness | 24 | 19 – 29 | Normal (σ₄) |

| x₅ | Crossbeam Thickness | 90 | 80 – 100 | Normal (σ₅) |

| x₆ | Main Housing Wall Thickness | 24 | 19 – 29 | Normal (σ₆) |

| x₇ | Cover Thickness | 14 | 9 – 19 | Normal (σ₇) |

Screening and Variable Selection: To improve computational efficiency, a global sensitivity analysis is performed to rank the influence of each design variable on the objective function \( f(X) \). Techniques like the Morris method or variance-based Sobol indices can be used. The results typically show that variables like the reinforcement rib thickness (\(x_3\)), baseplate thickness (\(x_1\)), and cover thickness (\(x_7\)) have the most significant impact on the global dynamic stiffness and thus the vibration response. Variables with negligible influence can be fixed at their initial values to reduce the problem dimensionality. For this study, we proceed with \(x_1\), \(x_3\), and \(x_7\) as the active design variables for robust optimization.

2.3 Optimization Process and Results

The robust optimization workflow integrates the finite element model with the 6σ algorithm. It involves the following steps:

1. Design of Experiments (DoE): A space-filling sampling method (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) is used to generate a set of design points within the variable ranges.

2. Simulation and Metamodeling: For each sample point, the finite element dynamic analysis is run to compute the objective function \( f(X) \). A metamodel (or surrogate model), such as a Kriging model, is then constructed to approximate the functional relationship \( f \approx \hat{f}(X) \) and its statistical moments (\( \mu_f, \sigma_f \)) based on the sampled data. This replaces thousands of expensive FE simulations with a fast-evaluating mathematical model.

3. 6σ Optimization Loop: An optimization algorithm (e.g., Sequential Quadratic Programming, Genetic Algorithm) works on the metamodel to solve the 6σ formulation from Section 2.1. It searches for the set of mean variable values \( \mu_X^* \) that minimize \( \mu_f + \kappa \sigma_f \).

4. Verification: The optimal design point is verified by running a full FE analysis to ensure accuracy.

The results of the 6σ robust optimization are presented in Table 6. The optimization algorithm converges to an optimal set of nominal dimensions.

| Variable | Initial Mean (mm) | Optimal Mean (mm) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| x₁ (Baseplate) | 14.0 | 13.43 | -4.1% |

| x₃ (Reinforcement Rib) | 10.0 | 11.39 | +13.9% |

| x₇ (Cover) | 14.0 | 12.49 | -10.8% |

The optimization suggests a nuanced redesign: thickening the strategically placed reinforcement ribs (\(x_3\)) to increase local stiffness, while slightly reducing the thickness of larger panels like the baseplate (\(x_1\)) and cover (\(x_7\)). This likely redistributes mass and stiffness more efficiently, altering the dynamic mode shapes and force transmission paths to attenuate vibration without adding unnecessary weight.

Dynamic Performance after Optimization: The optimized housing model is analyzed dynamically. First, a modal analysis confirms the natural frequencies shift slightly but maintain a safe margin from excitation frequencies (Table 7). Crucially, the forced vibration response shows dramatic improvement. The RMS vibration accelerations at all evaluation points are significantly reduced, as detailed in Table 8. The reduction exceeds 26.1% in all cases, with some directions showing improvements greater than 45%.

| Mode | Natural Frequency (Hz) | Change from Baseline |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 131.2 | +0.03% |

| 2 | 164.9 | -0.05% |

| 3 | 202.5 | +0.00% |

| 4 | 208.8 | -0.14% |

| 5 | 238.0 | -0.08% |

| 6 | 282.5 | +0.01% |

| 7 | 307.4 | -0.03% |

| 8 | 316.3 | -0.09% |

| Eval. Point | Direction | Baseline RMS (m/s²) | Optimized RMS (m/s²) | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | x | 58.81 | 32.24 | 45.2% |

| y | 44.08 | 29.09 | 34.0% | |

| z | 42.86 | 29.01 | 32.3% | |

| 2 | x | 50.34 | 30.58 | 39.3% |

| y | 46.17 | 27.05 | 41.4% | |

| z | 41.66 | 26.50 | 36.4% | |

| 3 | x | 49.87 | 29.30 | 41.2% |

| y | 43.82 | 28.50 | 35.0% | |

| z | 38.86 | 24.30 | 37.5% | |

| 4 | x | 57.78 | 33.12 | 42.7% |

| y | 54.40 | 31.05 | 42.9% | |

| z | 39.23 | 29.00 | 26.1% |

2.4 Assessment of Robustness and Reliability

The superiority of the 6σ approach lies in its explicit handling of uncertainty. To evaluate the robustness of the optimal design, we analyze the probability distributions of the objective function. Using Monte Carlo simulation on the established metamodel, we draw thousands of samples for the design variables \(x_1, x_3, x_7\) according to their normal distributions (with optimal means and original standard deviations \( \sigma \)) and evaluate the corresponding vibration objective \( f \).

The distribution of \( f \) for the initial and optimized designs can be compared. The optimized design will show:

1. A lower mean value (\( \mu_f \)), indicating better average performance.

2. A narrower distribution (smaller \( \sigma_f \)), indicating reduced sensitivity to manufacturing variations.

Furthermore, we can calculate the reliability of the design with respect to a specific performance limit. For instance, we might define a success criterion as “the vibration at point 1 in the x-direction is less than 40 m/s²”. The probability of meeting this criterion for the optimized design, considering variable uncertainties, is its reliability \( R \). For a constraint defined by an upper limit \( U \), assuming the response \( Y \) is normally distributed with mean \( \mu_Y \) and standard deviation \( \sigma_Y \), the reliability is:

$$ R = P(Y \leq U) = \Phi\left( \frac{U – \mu_Y}{\sigma_Y} \right) $$

where \( \Phi(\cdot) \) is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution. The Sigma level is \( Z = (U – \mu_Y)/\sigma_Y \). A 6σ process corresponds to \( Z \geq 4.5 \) (accounting for a typical 1.5σ mean shift), yielding a reliability greater than 99.99966%.

For our design variables themselves, we can assess the probability that they will remain within their specified manufacturing bounds (9-19 mm, etc.). Given their optimal mean \( \mu_X \) and standard deviation \( \sigma_X \), the probability of staying within bounds [L, U] is:

$$ R_X = \Phi\left( \frac{U – \mu_X}{\sigma_X} \right) – \Phi\left( \frac{L – \mu_X}{\sigma_X} \right) $$

For the optimized variables in Table 6 with reasonable assumed tolerances, these reliabilities are calculated to be above 97.1%, confirming that the optimal point is not pushed to the very edge of feasibility where it would be highly likely to fail tolerance checks during manufacturing. This is a direct benefit of the third line of the 6σ formulation (\( X^L + n\sigma_X \leq \mu_X \leq X^U – n\sigma_X \)), which keeps the nominal design away from the bounds.

3. Experimental Validation

To validate the optimization results, a prototype of the high-speed herringbone gear transmission system was manufactured according to the optimized design specifications. The experimental test rig consisted of a driving motor, a speed-increasing gearbox (to reach the required input speed), the test herringbone gearbox, and a load absorption unit. Tri-axial accelerometers were mounted on the gearbox housing at locations corresponding to the four evaluation points used in the simulation. Data acquisition hardware collected vibration signals at a high sampling rate while the system operated under rated conditions (6000 rpm input speed, rated load).

The recorded time-domain acceleration signals were processed identically to the simulation data: filtered to remove noise outside the frequency range of interest, and the RMS values were computed. The experimental results are summarized in Table 9.

| Evaluation Point | RMS Acceleration (m/s²) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| x-direction | y-direction | z-direction | |

| 1 | 29.60 | 27.46 | 26.54 |

| 2 | 27.50 | 25.83 | 23.29 |

| 3 | 26.38 | 25.00 | 24.58 |

| 4 | 28.81 | 27.00 | 26.83 |

Comparing Table 9 (experiment) with the “Optimized RMS” column in Table 8 (simulation) reveals a very close correlation. The discrepancies are within 13% for all measurements, which is considered excellent agreement for complex dynamic system prediction. This close match validates the accuracy of the finite element model and the overall optimization framework. The experiment confirms the significant vibration reduction achieved through the robust optimization process.

4. Conclusion

This work has demonstrated a complete and effective framework for the robust dynamic optimization of a high-speed herringbone gear transmission system. The methodology integrates high-fidelity finite element modeling, dynamic response analysis, and the 6σ robust optimization strategy to address the critical need for stable, low-vibration performance in the presence of real-world uncertainties.

Key findings and contributions include:

1. A dynamic model of the herringbone gear system was successfully established, incorporating time-varying mesh stiffness and realistic bearing dynamics, providing a reliable platform for performance evaluation.

2. The 6σ robust optimization formulation effectively identified optimal nominal dimensions for key housing features (baseplate, reinforcement rib, and cover thickness) while explicitly accounting for their manufacturing variations.

3. The optimized design achieved a dramatic reduction in housing vibration—exceeding 26.1% and reaching over 45% in some cases—compared to the initial baseline design.

4. The optimization process inherently enhanced the design’s robustness. The optimal point was not merely a performance peak but a robust plateau, ensuring that the vibration performance remains consistently good even when design variables deviate within their tolerance bands. The associated structural reliability was calculated to be above 97.1%.

5. Experimental testing on a prototype built to the optimized specifications confirmed the simulation predictions, with measured vibration levels closely matching the optimized values, thereby validating the entire approach.

The application of this robust optimization framework is not limited to herringbone gears. It is broadly applicable to any high-speed gear transmission system, including planetary gearboxes for wind turbines, aerospace reduction gearboxes, and high-performance vehicle transmissions. Future work could expand the scope of uncertainties to include variations in material properties, bearing clearance, and operational load fluctuations. Furthermore, multi-objective robust optimization could simultaneously target vibration, weight, and thermal performance, leading to even more comprehensive and reliable next-generation transmission system designs.